Chinese Exclusion Act facts for kids

|

|

| Nicknames | Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 47th United States Congress |

| Effective | May 6, 1882 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 47-126 |

| Statutes at Large | 22 Stat. 58, Chap. 126 |

| Legislative history | |

|

|

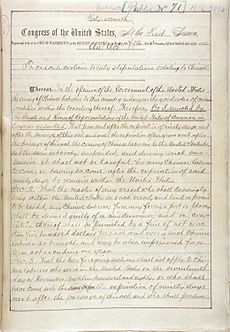

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a U.S. federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882. This law stopped almost all Chinese laborers from coming to the United States for 10 years. It did not apply to merchants, teachers, students, travelers, or diplomats.

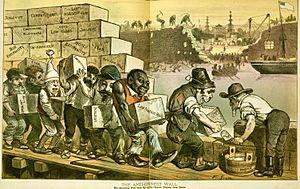

This act was the only U.S. law ever made to stop a specific ethnic or national group from immigrating. It built on an earlier law, the Page Act of 1875, which had already banned Chinese women from moving to the U.S.

Before this law, there was a lot of negative feeling and violence against Chinese people in the U.S. The law followed the Angell Treaty of 1880, which allowed the U.S. to pause Chinese immigration. The act was supposed to last for 10 years. However, it was made stronger in 1892 by the Geary Act and then made permanent in 1902. Even with these laws, many Chinese people still found ways to enter the country.

The Chinese Exclusion Act stayed in place until 1943. That year, the Magnuson Act finally ended the ban. It allowed 105 Chinese immigrants to enter the U.S. each year. Chinese immigration grew more with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which removed direct racial limits. It increased even more with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which got rid of the old National Origins Formula.

Contents

Why the Chinese Exclusion Act Happened

Chinese immigration to North America really started with the California Gold Rush in 1848. It continued as Chinese workers helped with big projects like building the Transcontinental Railroad. At first, during the gold rush, white miners mostly tolerated Chinese workers when gold was easy to find.

But as gold became harder to get, competition grew. This led to more anger toward Chinese and other foreign miners. After being forced out of mining, Chinese immigrants moved to cities, especially San Francisco. They took on jobs like restaurant and laundry work, which paid low wages.

Economic Troubles and Anti-Chinese Feelings

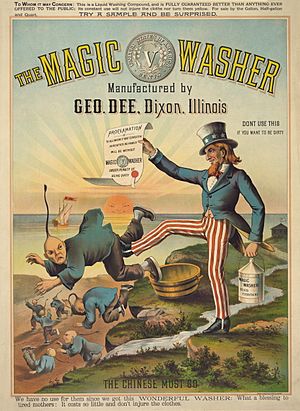

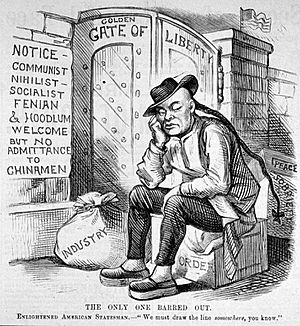

In the 1870s, after the Civil War, the U.S. economy was struggling. People started blaming Chinese workers for low wages. Leaders like Denis Kearney and California governor John Bigler said Chinese "coolies" (a disrespectful term for laborers) were causing the problem.

Public opinion and laws in California began to turn against Chinese workers. Many laws were passed to limit Chinese labor, behavior, and even living conditions. While some of these laws were quickly overturned by courts, many more anti-Chinese laws kept appearing.

In the early 1850s, some people didn't want to stop Chinese immigration. This was because Chinese workers paid important taxes that helped California's finances. However, as the state's money situation improved, efforts to ban Chinese people became more successful. In 1858, California tried to make it illegal for "Chinese or Mongolian races" to enter the state. But the State Supreme Court stopped this law in 1862.

Chinese immigrant workers provided cheap labor. They also didn't use many government services like schools or hospitals. This was because most Chinese migrants were healthy adult men. In 1868, the U.S. Senate approved the Burlingame Treaty with China. This treaty allowed Chinese people to enter the U.S. freely.

Growing Tensions and National Debate

As more Chinese migrants arrived, violence often broke out, especially in cities like Los Angeles. A strike in North Adams in 1870, where Chinese men replaced all the striking workers, sparked widespread protests. This event helped make Chinese immigration a major national issue.

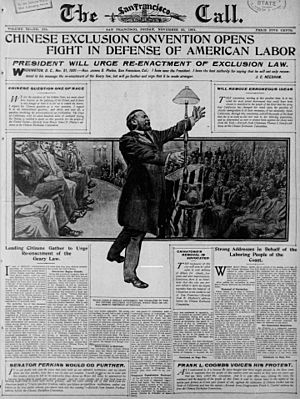

After the economy worsened in the Panic of 1873, Chinese immigrants were blamed for lowering workers' wages. At one point, Chinese men made up almost a quarter of all wage-earning workers in California. By 1878, Congress tried to ban immigration from China. President Rutherford B. Hayes vetoed this bill. A newspaper article from 1873, "The Chinese Invasion! They Are Coming, 900,000 Strong," shows how strong the anti-immigrant feelings were.

In 1879, California adopted a new Constitution. It allowed the state government to decide who could live there. It also banned Chinese people from working for companies or state, county, or city governments.

Three years later, after China agreed to change the treaty, Congress tried again to ban Chinese laborers. Senator John F. Miller of California proposed a new Chinese Exclusion Act. It would stop Chinese laborers from entering for 20 years. The bill passed both the Senate and House easily.

However, President Chester A. Arthur vetoed it. He felt a 20-year ban broke the 1880 treaty, which only allowed a "reasonable" pause in immigration. Newspapers in the eastern U.S. praised his veto, but people in the western states were angry. Congress could not override the veto.

So, Congress passed a new bill that reduced the ban to 10 years. The House of Representatives voted 201–37 to pass it. Even though President Arthur still disagreed with denying entry to Chinese laborers, he signed this compromise. The Chinese Exclusion Act became law on May 6, 1882.

After the act passed, many Chinese workers faced a hard choice. They could stay in the U.S. alone or return to China to be with their families. While many people disliked the Chinese, some business owners actually opposed the ban. They liked that Chinese workers accepted lower wages.

What the Chinese Exclusion Act Did

This law was the first federal law to stop an ethnic working group from entering the country. It claimed that this group was a danger to certain areas. (The earlier Page Act of 1875 had banned Asian forced laborers. The Naturalization Act of 1790 had stopped non-white people from becoming citizens.)

The act banned Chinese laborers, including "skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining." If they tried to enter, they faced prison and deportation.

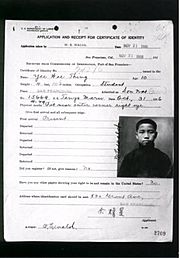

The few non-laborers who wanted to enter had to get special papers from the Chinese government. But it became very hard for them to prove they were not laborers. This was because the 1882 act defined almost everyone as a "laborer." So, very few Chinese people could enter under this law. Chinese diplomats and other officials on business, along with their servants, were allowed if they had the right papers.

The act also affected Chinese people already living in the U.S. If they left the country, they needed special papers to return. The law also made Chinese immigrants permanent foreigners. They could not become U.S. citizens. After the law passed, Chinese men in the U.S. had little chance of seeing their wives again or starting families.

Changes and Court Rulings

In 1884, changes were made to the law. These made it even harder for immigrants to leave and return. They also made it clear that the law applied to all ethnic Chinese, no matter where they were from. The Scott Act (1888) went further. It banned Chinese people from re-entering the U.S. after leaving. Only teachers, students, government officials, tourists, and merchants were exempt.

The U.S. Supreme Court said the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Scott Act were constitutional in 1889. The court stated that the government has the power to exclude foreigners. The act was renewed for 10 years by the Geary Act in 1892. It was made permanent in 1902. When it was extended in 1902, it required every Chinese resident to register and get a certificate. Without it, they could be deported.

Between 1882 and 1905, about 10,000 Chinese people went to federal court to challenge immigration decisions. Most of the time, the courts sided with the Chinese person. However, a law passed in 1894 limited these challenges. In 1905, the Supreme Court ruled that port inspectors had the final say on who could enter. This meant that even if a Chinese person was a U.S. citizen, they could be denied entry at the border. These events, along with the law's extension in 1902, led to a boycott of U.S. goods in China from 1904 to 1906.

One person who spoke out against the act was Senator George Frisbie Hoar from Massachusetts. He called it "nothing less than the legalization of racial discrimination."

Most people and unions strongly supported the Chinese Exclusion Act. This included the American Federation of Labor and Knights of Labor. They believed that factory owners were using Chinese workers to keep wages low. The Industrial Workers of the World was one of the only labor groups that opposed the act.

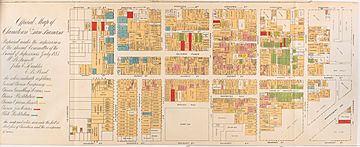

The Exclusion Act largely stopped the growth of the Chinese community in the U.S. Limited immigration continued until the law was repealed in 1943. From 1910 to 1940, the Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco Bay processed most Chinese immigrants. Many were sent back to China. The Chinese population in the U.S. dropped from about 105,000 in 1880 to 61,000 in 1920.

The act did allow merchants to enter. After a court ruling in 1915, restaurant owners could apply for merchant visas. This led to a quick growth of Chinese restaurants in the 1910s and 1920s. Restaurant owners could leave and re-enter with family members from China.

Later, the Immigration Act of 1924 restricted immigration even more. It banned all Chinese immigrants and extended limits to other Asian groups. Until these rules were eased in the mid-1900s, Chinese immigrants had to live apart from their families. They built ethnic communities called Chinatowns to survive.

The Chinese Exclusion Act did not solve the problems white workers faced. In fact, Japanese immigrants quickly replaced Chinese workers in many jobs. Unlike the Chinese, some Japanese people were able to start businesses. However, the Japanese were later targeted by the Immigration Act of 1924, which banned all immigration from East Asia.

In 1891, the Chinese government refused to accept U.S. senator Henry W. Blair as a minister to China. This was because of his harsh comments about China during the talks for the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The "Driving Out" Period

After the Chinese Exclusion Act passed, a time called the "Driving Out" era began. During this period, anti-Chinese Americans physically forced Chinese communities to leave their homes. Large-scale violence happened in Western states. Two examples are The Rock Springs Chinese Massacre (1885) and the Hells Canyon massacre (1887).

Rock Springs Massacre of 1885

This massacre happened in Rock Springs, Wyoming. White miners were jealous of the Chinese workers who had jobs. White miners attacked Chinese people in Chinatown. Many Chinese people tried to run away. Some died from hunger while hiding or were attacked by animals in the mountains. A passing train rescued some. In the end, at least 28 lives were lost.

The government sent federal troops to protect the Chinese. However, only money for destroyed property was paid. No one was arrested or held responsible for the terrible acts committed during the riot.

Hells Canyon Massacre of 1887

This massacre took place along the Snake River in Hells Canyon. This area had dangerous rocky cliffs and fast-moving water. Thirty-four Chinese miners were killed there. These miners worked for the Sam Yup company, one of the largest Chinese companies at the time.

The exact details of what happened are still unclear. This is because law enforcement was unreliable, news reports were biased, and there were no serious official investigations. However, it is believed that the Chinese miners were killed by a gang of seven armed horse thieves. Gold worth $4,000–$5,000 was thought to have been stolen from the miners. The gold was never found or investigated further.

Aftermath of the Massacres

After the Hells Canyon incident, the Sam Yup company hired someone to investigate. A U.S. Commissioner, Joseph K. Vincent, led the investigation. He sent his report to the Chinese consulate, who tried to get justice for the miners. But they were not successful. Other requests for payment for earlier crimes against Chinese people also failed.

Finally, on October 19, 1888, Congress agreed to pay a much smaller amount of money for the Hells Canyon massacre. They ignored the claims for earlier crimes. Even though the payment was small, it was a small victory for the Chinese, who had not expected any help or recognition.

Impact on Education in the U.S.

Bringing foreign students to U.S. colleges was important for spreading American influence. International education helped students learn from top universities. They could then take their new skills back to their home countries. This was seen as a way to improve diplomatic relations and trade.

However, the U.S. Exclusion Act made it hard for Chinese students. They had to prove they were not trying to get around the rules. These laws created difficult situations for Chinese students. This led to criticism of American society. The policies and attitudes toward Chinese Americans actually hurt U.S. foreign policy. They limited America's ability to take part in international education.

Repeal and Current Status

The Chinese Exclusion Act was finally ended by the Magnuson Act in 1943. By then, China had become an ally of the U.S. against Japan in World War II. The U.S. wanted to show itself as fair and just. The Magnuson Act allowed Chinese people already living in the U.S. to become citizens. They no longer had to hide from deportation.

The act also allowed Chinese people to send money to family members in China and other places. However, the Magnuson Act only allowed a yearly quota of 105 Chinese immigrants. It did not remove limits on immigration from other Asian countries.

In its last decade (1956 to 1965), the crackdown on Chinese immigrants got even tougher. The Immigration and Naturalization Service started the Chinese Confession Program. This program encouraged Chinese people who had lied about their immigration status to confess. They hoped to get some leniency. Large-scale Chinese immigration did not happen until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was passed.

The first Chinese immigrants under the Magnuson Act were college students. They wanted to escape the war in China during World War II and study in the U.S. But when the People's Republic of China was formed and entered the Korean War against the U.S., some American politicians worried. They feared that American-educated Chinese students would take U.S. knowledge back to "Red China." Many Chinese college students were almost forced to become citizens. Even so, they still faced a lot of prejudice and discrimination.

Even though the exclusion act was repealed in 1943, a law in California banning non-white people from marrying white people stayed until 1948. The California Supreme Court then ruled this ban unconstitutional. Some other states had such laws until 1967. That year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that all anti-interracial marriage laws across the nation were unconstitutional.

Today, Chapter 7 of Title 8 of the United States Code is still called "Exclusion of Chinese." It is the only chapter focused completely on one nationality or ethnic group. Like the next chapter, "The Cooly Trade," it only contains laws that have been "Repealed" or "Omitted."

On June 18, 2012, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution. It formally expressed the House's regret for the Chinese Exclusion Act. This act had placed huge limits on Chinese immigration and citizenship. It denied Chinese-Americans basic freedoms because of their ethnicity. The U.S. Senate had approved a similar resolution in October 2011.

In 2014, the California Legislature also formally recognized the achievements of Chinese-Americans. They called on Congress to apologize for the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. These resolutions celebrated Chinese-American history and contributions. They also formally asked Congress to apologize for laws that led to the unfair treatment of Chinese Americans.

This history shows how minorities can be treated unfairly during times of economic or political trouble. When society is stable, tensions between groups tend to lessen. But during times of crisis, negative feelings against workers from other nations can rise. This often leads to unfair actions by institutions and society.

See also

In Spanish: Ley de Exclusión China para niños

In Spanish: Ley de Exclusión China para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |