Coolie facts for kids

A coolie is a term that was used for a worker who earned very low wages, often from South Asia or East Asia.

The word "coolie" became common in the 1500s when European traders used it across Asia. By the 1700s, it referred to Indian workers who traveled to other countries for jobs under special contracts. In the 1800s, during the time of British rule, it took on a new meaning. It described the organized shipping and hiring of Asian workers to labor on plantations. These were often the same plantations where enslaved African people had worked before.

Today, the word "coolie" can be seen as offensive or a bad word, depending on where and when it's used. In India, where the word came from, it is still considered a very insulting term. It's especially seen as a racial slur in places like the Caribbean, parts of Africa, Southeast Asia, and Oceania. This is because it refers to people of Indian descent whose ancestors moved to former British colonies. These places include South Africa, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Fiji.

In modern Indian movies, coolies are sometimes shown as working-class heroes. Famous Indian films that feature coolies include Deewaar (1975) and Coolie (1983).

Contents

A Look Back: The History of Coolie Labor

Why Did Coolie Labor Start?

Bringing Asian workers to European colonies was not new, starting as early as the 1600s. However, in the 1800s, a much larger system of "coolie" trade began. This happened because the trade of enslaved African people was ending, and slavery was no longer the main way to get workers for plantations in many European colonies.

The British were the first to try using coolie labor. In 1806, 200 Chinese workers were sent to the colony of Trinidad. The very next year, in 1807, Britain made the African slave trade illegal. The first attempt in Trinidad was not very successful. But these early efforts inspired people like Sir John Gladstone to find coolies for his sugar farms in British Guiana. He hoped they would replace the African workers after slavery was ended in Britain in 1833.

Other European countries like France, Spain, and Portugal soon followed. They also started bringing in Asian workers. In places like the British Empire, this began seriously after slavery was abolished. In other places, like Cuba, African slavery continued for many more years, even after coolies were introduced.

Was Coolie Labor Like Slavery?

Because coolie labor started around the same time slavery was ending, many people wondered if it was just another form of slavery or truly free work.

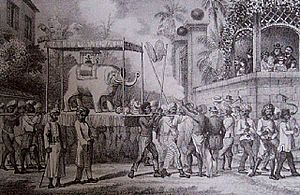

People who supported coolie labor said it was free because workers signed a contract. This contract was supposed to explain what the worker and employer had to do. For example, in Cuba, contracts for Chinese workers were printed in both Chinese and Spanish. They would include details like the worker's name, age, and hometown. The contract usually promised about 1 peso a week, plus food and clothes, for eight years of work. It also said workers would get some days off and medical care. The government also had rules for how workers were recruited, transported, and employed. Supporters said coolie labor was different from slavery because it was based on a contract, was voluntary, paid, and temporary. Workers were supposed to be completely free after their contract ended.

However, many people who were against coolie labor said that abuse and violence were very common. Workers often signed up for two to five years. They had their travel paid for, but they were paid very little, often less than 20 cents a day. More than a dollar was taken from their pay each month to cover their debts. This system of "indentured servitude" made it seem like "free" labor, but it still gave Europeans many benefits similar to slavery.

The coolie trade was often compared to the earlier slave trade because they achieved similar things. Like slave plantations, some Caribbean estates had over 600 coolies, with Indians making up more than half. There were also unfair ideas about how different groups of people worked. Some believed Chinese and Japanese coolies worked harder and were cleaner, while Indian coolies were seen as having lower status and needing constant watching. This system helped the British economy, as they needed manual labor for their profitable plantations after slavery became illegal.

Abolitionists in Britain and the U.S. strongly criticized coolie labor, saying it was no better than slavery.

Chinese Workers: Their Journey and Hardships

Many Chinese workers were sent to Peru and Cuba. However, many also worked in British colonies like Singapore, Jamaica, and British Guiana (now Guyana). They also went to Dutch colonies in the East Indies and Suriname. The first group of Chinese laborers arrived in Trinidad in 1806. On many trips, workers were transported on the same ships that had carried enslaved Africans years before.

The coolie-slave trade, often run by American captains, was called the "pig trade" because living conditions were so bad. On some ships, as many as 40 out of every 100 coolies died during the journey. Up to 500 people were crammed into a single ship's hold, with no room to move. Some Chinese women were even kidnapped to be forced into labor. Workers had to pay for their ship fares from their tiny earnings, which often meant they were trapped in a system like slavery.

This trade grew from 1847 to 1854. But then, reports of mistreatment in Cuba and Peru started to appear. The British government closed many ports involved in the trade. However, the trade simply moved to Macau, a Portuguese area.

Many coolies were tricked or kidnapped. They were held in special centers or on ships in the departure ports, just like African slaves. Their voyages across the Pacific were as cruel and dangerous as the famous "Middle Passage" of the Atlantic slave trade. Many people died. It's estimated that between 1847 and 1859, about 15 out of every 100 coolies died on ships to Cuba. For ships going to Peru, this number was as high as 40 out of 100 in the 1850s.

Once they arrived, they were sold and forced to work on plantations or in mines. Conditions were terrible. Contracts usually lasted five to eight years, but many coolies died before their time was up due to hard work and abuse. Survivors were often forced to keep working even after their contracts ended. For example, 75 out of 100 Chinese coolies in Cuba died before finishing their contracts.

Because of these awful conditions, Chinese coolies often rebelled. They were often placed in the same neighborhoods as African people. Since most could not return home or bring their families, many Chinese men married African women. These mixed-race relationships helped create new populations in the Americas.

In Spanish, coolies were called colonos asiáticos. The Spanish colony of Cuba feared slave uprisings, so they used coolies as a way to move from slavery to free labor. These workers were neither fully free nor fully enslaved. Even after slavery was abolished in Cuba in 1884, indentured Chinese workers continued to labor in the sugarcane fields. Some historians believe that despite their contracts, Chinese coolies in Cuba were slaves in all but name. However, others argue that coolies could challenge their bosses, run away, or ask government officials for help, which slaves could not. After their contracts were done, many colonos asiáticos settled in countries like Peru, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba. They adopted local traditions and shared their own culture.

In the United States, debates about coolie labor and slavery greatly affected the history of Chinese immigrants. In 1862, a law called the "Anti-Coolie Act" was passed. It stopped U.S. citizens from trading in Chinese "coolies." This law was partly about ending the slave trade and partly about starting to limit Chinese immigration. In 1868, the Burlingame Treaty tried to protect Chinese immigrants and said that any Chinese person coming to the U.S. must do so freely. Later laws, like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, completely stopped Chinese laborers from entering the U.S.

Despite these efforts to limit cheap labor from China, Chinese workers helped build many important projects. In the 1870s, they built a huge network of levees in California, making farmland available. Chinese workers also helped build the first Transcontinental Railroad in the U.S. and the Canadian Pacific Railway. However, after these projects were finished, Chinese settlement was often discouraged. Laws were passed to target Chinese immigrants. For example, California's constitution in 1879 stated that "Asiatic coolieism is a form of human slavery, and is forever prohibited."

The term "coolie" was also used for Chinese workers on cacao farms in German Samoa. A Chinese official reported the cruel treatment of these workers in 1908. This trade lasted until 1914, and most of the 2,000 Chinese "coolies" there were eventually sent home.

By 1874, the coolie trade was finally stopped due to public outcry and pressure from the British and Chinese governments. By then, up to half a million Chinese workers had been sent abroad.

Indian Workers: Their Journey and Hardships

By the 1820s, many Indian people were choosing to go abroad for work, hoping for a better life. European traders quickly saw this as a chance to get cheap labor. The British began sending Indians to colonies all over the world, including Mauritius, Fiji, British Natal, British East Africa, and many parts of the Caribbean like Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica. The Dutch sent workers to Suriname, and the French sent them to Guadeloupe and Réunion.

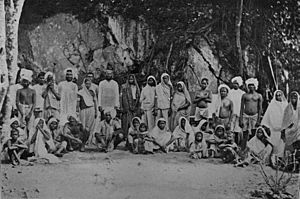

Agents would go into Indian villages to recruit workers. They often tricked people with false promises of great opportunities abroad. Most Indian workers came from the Indo-Gangetic Plain, but also from other areas. Indians faced many social and economic problems, including frequent famines, which made them more willing to leave their homes.

The British started sending Indians to Mauritius in the Indian Ocean in 1829. After slavery ended there, plantation owners brought in many indentured laborers from India to work in the sugar cane fields. Between 1834 and 1921, about half a million indentured laborers worked on the island.

In 1837, the British authorities in India set up rules for the trade. These rules said that each worker had to be approved by a government officer. The work contract was limited to five years, and the employer had to pay for the worker's return trip. Ships also had to meet basic health standards.

However, conditions on the ships were often very crowded, with lots of disease and not enough food. Workers were often not told how long the trip would be or where they were going. They were paid very little and had to work in terrible conditions. While there weren't many big scandals about abuse in British colonies, workers were often forced to stay and were tricked into depending on the plantation owners. This meant they often stayed long after their contracts ended. Only about 10 out of every 100 coolies actually returned home.

The journey itself was very dangerous, especially for women. Even though rules were sometimes in place to prevent harm, crimes against women and children were common, and those who committed them were rarely punished.

Still, the British authorities did try to control the worst abuses. Health inspectors regularly checked on workers, and people were checked before traveling to make sure they were healthy enough for the hard work. Children under 15 were not allowed to be separated from their parents for transport.

In England, a campaign against the "coolie" trade started, comparing it to slavery. Because of this pressure, the export of workers was temporarily stopped in 1839. But it soon started again because it was so important for the economy. Stricter rules were put in place in 1842. In that year, almost 35,000 people were sent to Mauritius.

In 1844, the trade expanded to the Caribbean, including Jamaica, Trinidad, and Demerara. The Asian population soon became a major part of the people living on these islands.

Starting in 1879, many Indians were sent to Fiji to work on sugar cane farms. Many chose to stay after their contracts ended, and today they make up about 40% of Fiji's population. Indian workers were also brought to the Dutch colony of Suriname after a treaty was signed in 1870. In Mauritius, people of Indian descent are now the largest group, and Indian festivals are celebrated as national holidays.

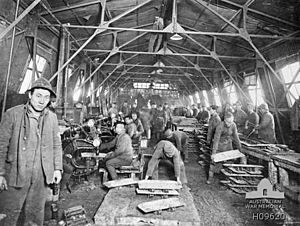

This system continued until the early 1900s. Media reports about the harsh conditions and abuses led to public anger. The British government officially ended the coolie trade in 1916. By that time, tens of thousands of Chinese workers were also being used by the Allied forces during World War I.

The Word "Coolie" Today

The word "coolie" is used differently around the world today:

- In Indonesian, kuli means a construction worker. It is mostly not seen as offensive, but some people find it offensive because it was used to put down Javanese people who became coolies.

- In Malaysia, kuli means a manual laborer and has a slightly negative feeling.

- In Thai, kuli (กุลี) still means manual laborers but is considered offensive.

- In South Africa, coolie referred to Indian indentured workers. It is now a very insulting term for people of Indian descent.

- In Hindi, qūlī is commonly used for luggage porters at railway stations. However, using it (especially by foreigners) can still be seen as an insult by some.

- In Ethiopia, cooli refers to people who carry heavy loads. It is not used as an insult there.

- The Dutch word koelie means a worker who does very hard labor. It usually doesn't have ethnic meaning for Dutch people, but it is a racial slur for people of Indian heritage in Suriname.

- Among Vietnamese people living abroad, coolie ("cu li" in Vietnamese) means a laborer. Recently, it has also come to mean someone who works a part-time job.

- In some Caribbean countries like Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, and Fiji, coolie is sometimes used to refer to anyone of South Asian descent. It is used in a racially offensive way by non-Indians towards Indians in these countries.

- The conical Asian hat worn by many Asians to protect from the sun is sometimes called a "coolie hat."

- In the technology industry, workers in other countries who are paid less are sometimes called 'coolies'.

- In Hungarian, "kulimunka," meaning "coolie work," refers to very hard, repetitive tasks.

- In Sri Lanka (Sinhala), "kuliwada" means manual labor. "Kuli" can also mean working for a fee, especially instant cash payment. It can be used in a joking or insulting way to mean biased actions.

- In Filipino, makuli means "industrious," which can have a meaning of being like a slave.

See also

In Spanish: Culí para niños

In Spanish: Culí para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |