George Frisbie Hoar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

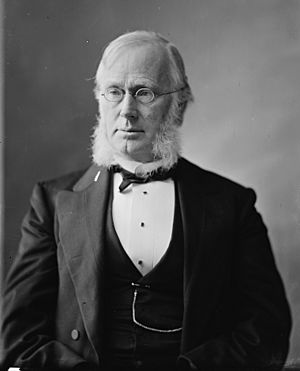

George F. Hoar

|

|

|---|---|

Hoar c. 1870s

|

|

| United States Senator from Massachusetts |

|

| In office March 4, 1877 – September 30, 1904 |

|

| Preceded by | George S. Boutwell |

| Succeeded by | Winthrop M. Crane |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts |

|

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1877 |

|

| Preceded by | John Denison Baldwin |

| Succeeded by | William W. Rice |

| Constituency | 8th district (1869–73) 9th district (1873–77) |

| Member of the Massachusetts Senate from the Worcester district |

|

| In office January 7, 1857 – January 5, 1858 Serving with J. F. Hitchcock, William Mixter, Velorus Taft, and Ohio Whitney, Jr.

|

|

| Preceded by | Francis H. Dewey Jabez Fisher Artemas Lee Salem Towne |

| Succeeded by | John M. Earle (redistricting) |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from the Worcester district |

|

| In office January 7, 1852 – January 4, 1853 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 29, 1826 Concord, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | September 30, 1904 (aged 78) Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican (after 1855) |

| Other political affiliations |

Free Soil (before 1855) |

| Alma mater | Harvard University Harvard Law School |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

George Frisbie Hoar (born August 29, 1826 – died September 30, 1904) was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1877 until his death in 1904. He came from a well-known family in New England that was active in politics.

Hoar was an abolitionist, meaning he was against slavery. He was also a Radical Republican, a group that strongly supported equal rights for African Americans. He grew up in a family that opposed unfair treatment based on race.

Friends often called him by his middle name, "Frisbie."

Contents

Early Life and Education

George F. Hoar was born in Concord, Massachusetts, on August 29, 1826. He went to a boarding school in Waltham, Massachusetts. Later, he graduated from Harvard University in 1846. He then earned his law degree from Harvard Law School in 1849.

After finishing law school, he became a lawyer and moved to Worcester, Massachusetts. He first joined the Free Soil Party, which opposed the spread of slavery. Later, he became a member of the Republican Party soon after it was formed.

Political Career Highlights

Hoar began his political career in Massachusetts. He was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1852. Then, he served in the Massachusetts Senate in 1857.

Serving in Congress

He became a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for Massachusetts. He served four terms from 1869 to 1877. After that, he was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1877. He served in the Senate until he died during his fifth term.

During one of his terms in the House (1873-1875), his brother, Ebenezer R. Hoar, also served alongside him. George Hoar was a Republican. He often spoke his mind, even if it meant criticizing members of his own party. He did this when he felt their actions were wrong.

Key Political Stances

Hoar believed in protecting American businesses from foreign competition. He thought this would help the country's economy grow. He also believed in a strong national currency. He opposed ideas like printing more money without backing it with valuable metals like gold.

In 1874, a famous senator named Charles Sumner was dying. He asked Hoar to make sure a new law, the Civil Rights Act of 1875, was passed. This law aimed to give equal rights to African Americans. Hoar worked hard to pass the bill, even though it became law in a weaker form.

Hoar was known for fighting against political corruption. He also supported the rights of African Americans and Native Americans. He backed the Dawes Act, which aimed to divide tribal lands among individual Native Americans. This act was controversial because it changed traditional ways of life.

He was against the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. He called it "nothing less than the legalization of racial discrimination." This law stopped Chinese laborers from coming to the U.S.

Hoar was part of the group that decided the very close 1876 United States presidential election. He also wrote the law that explains who becomes president if the president dies or leaves office. This was the Presidential Succession Act of 1886.

Supporting Women's Rights

As early as 1886, Hoar spoke in the Senate in favor of women's suffrage, which means women's right to vote. He was one of only a few senators who voted against the Edmunds–Tucker Act of 1887. This act took away women's right to vote in Utah.

Opposing Imperialism

Hoar was a strong opponent of American imperialism. This means he was against the U.S. taking control of other countries. He did not support American involvement in Cuba in the late 1890s.

He also met with leaders from Hawaii who were against the U.S. taking over their nation. He helped stop President William McKinley's plan to annex Hawaii by treaty. However, the islands were eventually annexed by a different method.

After the Spanish–American War, Hoar spoke out against the McKinley administration's expansionist policies. He strongly criticized the Philippine–American War. He called for the Philippines to become independent. In a long speech, he talked about the lives lost and the suffering caused by the war. He said that the American flag, which was once seen as a symbol of freedom, was now seen as a symbol of cruelty by many Filipinos.

Hoar helped create the Lodge Committee. This committee investigated claims of war crimes during the Philippine–American War, which were later confirmed. He also spoke out against the U.S. getting involved in Panama.

Other Interests and Contributions

In 1865, Hoar helped start the Worcester County Free Institute of Industrial Science. Today, this school is known as the Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

He was very active in historical societies. He served as president of both the American Historical Association and the American Antiquarian Society. He also helped found the American Irish Historical Society in 1887.

Hoar was a trustee for the Smithsonian Institution and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Thanks to his efforts, a very important historical document, Of Plymouth Plantation, written by William Bradford, was returned to Massachusetts. This document was discovered in London in 1855.

In 1901, he became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His autobiography, Autobiography of Seventy Years, was published in 1903.

George F. Hoar died in Worcester on September 30, 1904. He was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord. After his death, a statue of him was put up in front of Worcester's city hall. People donated money to pay for it.

Family Life

George F. Hoar was married twice. In 1853, he married Mary Louisa Spurr. They had a son, Rockwood Hoar, who also became a U.S. Representative, and a daughter, Mary. After Mary Louisa died, he married Ruth Ann Miller in 1862. They had a daughter named Alice.

His family had many important political figures:

- His mother, Sarah Sherman, was the granddaughter of Roger Sherman. Roger Sherman was a very important political figure who signed the Articles of Confederation, the United States Declaration of Independence, and the U.S. Constitution.

- His father, Samuel Hoar, was a well-known lawyer. He served in the Massachusetts state senate and the United States House of Representatives.

- His brother, Ebenezer R. Hoar, was a judge and served as the U.S. Attorney General.

- His cousin, Roger Sherman Baldwin, was the Governor of Connecticut and a U.S. Senator. Another cousin, William Maxwell Evarts, was a U.S. Secretary of State and U.S. Senator.

- He was the uncle of U.S. Representative Sherman Hoar.

See also

- List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–1949)