History of Panama facts for kids

The history of Panama tells the story of the Isthmus of Panama before and after Europeans arrived.

Long ago, before Europeans came, many different groups of people lived in Panama. They spoke languages like Chibchan, Choco, and Cueva. We don't know exactly how many people lived there, but some guess it was up to two million. They mostly fished, hunted, gathered food, and grew crops like corn and squash. Their homes were simple huts made of wood and mud, with roofs of palm leaves.

The first lasting European town was Santa María la Antigua del Darién, started in 1510. It was near the Tarena River on the Atlantic side. But in 1519, people moved to a new town called Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Panamá, which is now Panama City. This was the first European town on the Pacific Ocean.

Panama was part of the Spanish Empire for over 300 years, from 1513 to 1821. Its importance to Spain changed over time. In the 1500s and 1600s, it was super important for trade and travel.

On November 10, 1821, people in a place called Azuero declared they were breaking away from Spain. After independence, a small group of wealthy families, often called rabiblanco (meaning "white tail"), kept control.

In 1852, Panama started using juries for criminal trials. Also, 30 years after slavery was officially ended, it was finally stopped and enforced in Panama.

Contents

Ancient History of Panama

The oldest things found in Panama are Paleo-Indian projectile points, which are like spear tips. Later, central Panama was one of the first places in the Americas to make pottery. This was around 2500–1700 BC. Over time, large groups of people lived here. We know about them from special burials and colorful pottery. Huge stone sculptures at the Barriles site also show how advanced these ancient cultures were.

Many different groups lived in Panama, speaking languages like Chibchan, Choco, and Cueva. The Cueva people were a large group, and their language might have been used for trade. We don't know the exact number of people before Europeans arrived, but estimates range from 200,000 to two million. Old findings and stories from early European explorers show that these groups were diverse. They were already trading with each other across the region. They hunted, gathered plants, and grew crops like corn and cacao. Their homes were small huts made of palm leaves and branches, with hammocks inside.

Panama Under Spanish Rule

In 1501, Rodrigo de Bastidas was the first European to explore the Isthmus of Panama by sailing along its eastern coast. A year later, Christopher Columbus explored areas like Bocas del Toro and Portobelo on his fourth trip. Soon, Spanish explorers came to this land, which they called Tierra Firma (meaning "mainland").

In 1509, two Spanish leaders, Alonso de Ojeda and Diego de Nicuesa, were allowed to start colonies in the area. The goal was to create a single government, like what later became Mexico. Panama's region also gained control over other islands like Jamaica and the Cayman Islands.

First European Settlement

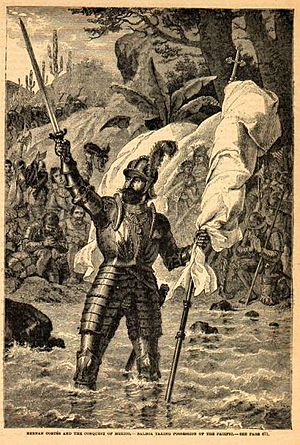

In September 1510, the first lasting European town on the American mainland was founded. It was called Santa María la Antigua del Darién. Vasco Nuñez de Balboa and Martín Fernández de Enciso chose a spot near the Tarena River on the Atlantic side. Balboa became the mayor of this new town. In 1513, the first Catholic Bishop in the Americas was appointed there.

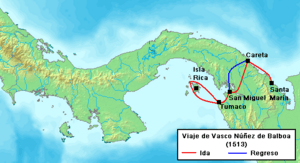

Balboa's Journey to the Pacific

On September 25, 1513, the Balboa expedition confirmed what local people had said: there was another ocean to the southwest of Panama. Balboa was the first European known to see this ocean, which he called the South Sea (now the Pacific Ocean).

Balboa's exciting descriptions of Panama made Ferdinand II of Aragon, the King of Spain, very interested. He called the land Castilla Aurifica (Golden Castille) and sent Pedro Arias Dávila (Pedrarias Davila) as the new governor. Pedrarias arrived in June 1514 with a large fleet of 22 ships and 1,500 men.

Spanish Colonization of Panama

On August 15, 1519, Pedrarias moved the capital from Santa María la Antigua del Darién. He founded Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Panamá (today's Panama City) on the Pacific coast. This was the first European town on the Pacific Ocean.

From about 1520, people from Genoa, Italy, controlled the port of Panama. They had permission from Spain to use the port mainly for the slave trade in the new world. This continued until the city was destroyed in 1671.

Governor Pedrarias also sent explorers to other areas. He was part of the agreement that led to the conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru by Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro.

Panama was part of the Spanish Empire for over 300 years. Its importance changed with how useful the narrow land strip was to Spain. In the 1500s and 1600s, it was the most important place for trade and strategy.

Pedrarias started building important routes across Panama, like the "Camino Real" and "Camino de Cruces." These roads connected Panama City on the Pacific with Nombre de Dios (and later Portobelo) on the Atlantic. This allowed Spain to send its "Treasure Fleets" full of riches across the ocean. It's thought that 60% of all the gold sent to Spain from the New World between 1531 and 1660 passed through Nombre de Dios/Portobelo.

Explorers leaving Panama found new lands and riches in Central and South America. People also looked for a natural waterway between the Atlantic and Pacific to reach Asia. Panama became important because it was in the middle of two oceans. Traders often passed through Panama on their way to Cuba and then to Spain. It also connected Southeast Asia and Latin America through the Manila Galleons.

Royal Court of Panama

In 1538, the Audiencia Real de Panama (Royal Court of Panama) was set up. It was a court system that covered a huge area, from Nicaragua all the way to the tip of South America.

Panama City, on the Pacific coast, was safer from pirates than the Atlantic side. But on January 28, 1671, the pirate Henry Morgan attacked and burned the city. It was rebuilt in 1673, about 8 km away from the old ruins. The old city ruins are now a popular tourist spot.

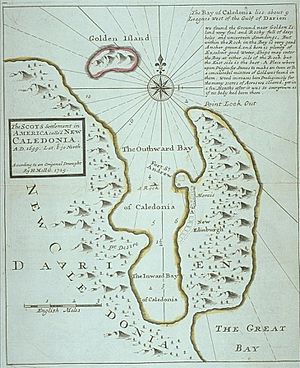

In 1698, a Scottish colony called "New Caledonia" was started near the Gulf of Darien. This plan failed, and the debt from it helped lead to Scotland joining with England in 1707 to form Great Britain.

When Panama was colonized, many native people died from diseases, attacks, and slavery. Those who survived fled into the forests and islands. Enslaved Africans were brought in to replace the native workers.

Panama developed a strong sense of being its own place, even before other colonies. This was because it was rich for a long time (1540–1740) and had a lot of power with its own court system. It played a key role in the Spanish Empire, which was the first global empire.

By the mid-1700s, Panama's importance began to fade. Spain's power in Europe was getting weaker, and ships found new ways to sail around South America (Cape Horn) to reach the Pacific. The Panama route was short but hard and costly, needing goods to be loaded and unloaded many times. It was also attacked by pirates and by cimarrons, who were escaped enslaved people living in communities. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, people moved away from Panama City, and the economy changed from trade to farming.

Spain created the Viceroyalty of New Granada (northern South America) in 1713 to protect its Caribbean lands. Panama was placed under its control. But the capital, Santa Fe de Bogotá, was very far away. Panama often disagreed with Bogotá, preferring its old ties to Peru. This difficult relationship lasted for a century.

Panama's Independence

In 1819, New Granada finally became free from Spain. Panama and other areas of New Granada were then technically free. Panama thought about joining Peru or other Central American groups. But it was convinced by Simón Bolívar's idea of a Gran Colombia, a large new country. Panama declared its independence in 1821 and joined this southern federation.

The city of Panama and the central trade route were very important to the Spanish Empire. This led to differences between regions. The Azuero region was more liberal and wanted independence, while Veraguas was more loyal to Spain. When the "Grito de la Villa de Los Santos" (a cry for independence) happened, Veraguas strongly opposed it.

How the Independence Movement Started

Panama's independence movement was partly helped by the end of the encomienda system in Azuero in 1558. This system, where Spanish settlers controlled native labor, was stopped because locals protested against bad treatment of native people. Instead, smaller land ownership was encouraged, taking power away from large landowners.

However, the end of this system in Azuero led to the conquest of Veraguas that same year. Under Francisco Vázquez, Veraguas came under Spanish rule in 1558. In this new area, the old encomienda system was brought back.

The Role of Printing

After Veraguas was conquered, the two regions, Azuero and Veraguas, disliked each other. Azuero saw itself as a place of people's power, while Veraguas represented the old, strict Spanish rule. Veraguas, on the other hand, saw itself as loyal and moral, while Azuero was seen as rebellious.

The tension grew when the first printing press arrived in Panama in 1820. A newspaper called La Miscelánea was created. Writers from Panama and Colombia wrote articles that spread ideas of freedom and independence. They wrote about the French Revolution, Bolívar's battles, and the United States gaining freedom from Britain.

These ideas spread quickly in the capital and Azuero, encouraging separatists. But in Veraguas, people remained loyal to Spain.

José de Fábrega and the Break from Spain

On November 10, 1821, the people of Azuero declared their separation from Spain in an event called Grito de La Villa de Los Santos. This surprised people in Veraguas and Panama City. Veraguas saw it as treason, while the capital thought it was too rushed.

The Grito event deeply affected Panama. It showed the Azuero people's strong desire for freedom. They were against the independence movement in the capital, who thought they should be in charge after the Spanish left.

Azuero's move was very brave, as they feared a quick response from Colonel José de Fábrega, who controlled the military. However, separatists in the capital had convinced Fábrega to join their side. This happened after the previous governor left him in charge in October 1821. So, after Azuero's declaration, Fábrega gathered all the separatist groups in the capital. He officially declared the city's support for independence. There were no military problems because royalist troops were cleverly bribed.

With Fábrega's help, the Spanish rule in Panama was over. Fábrega worked with separatists to hold a national meeting. Every region, even the loyalist Veraguas, attended. They realized nothing more could be done for Spain in Panama. So, on November 28, 1821, the meeting declared the independence of Panama. It also decided to join New Granada and Venezuela in Bolívar's new Republic of Colombia.

Fábrega wrote to Bolívar about the event, expressing his joy and pride. Bolívar replied, saying he was filled with joy and admiration. He called Panama's act of independence "the most glorious monument that any American province can give."

Panama and Colombia

Simón Bolívar wasn't sure about including Panama in his Gran Colombia plan. He knew Panama's unique geography and its history as a trade hub. He also hadn't played a direct role in Panama's independence, unlike in Venezuela, New Granada, and Ecuador. Bolívar knew Panama had cultural ties to South America but was geographically part of Central America. He once wrote that Panama could become "the center of the Universe" and "the emporium of the universe" because of its location between two oceans.

However, in 1821, Panama decided to join Venezuela, New Granada (now Colombia), and Ecuador. This new country was called the Republic of Colombia (or ‘Gran Colombia’). Even though Panama was part of this larger area, its economic ties had been closer to Peru.

In June 1826, a meeting called the Anfictionic Congress was held in Panama City. Representatives from new American countries gathered. Bolívar wanted to unite them to defend the continent from European powers.

In September 1830, Panama separated from the Republic of Colombia. General José Domingo Espinar led this move. He asked Bolívar to take direct control of Panama. But Bolívar refused and told Panama to rejoin the main country.

As the Republic of Colombia faced problems, Bolívar's dream of a united territory fell apart. A general named Juan Eligio Alzuru led a military takeover against Espinar. After things settled down, Panama rejoined what was left of the republic in early 1831. This new country was called the Republic of New Granada. This alliance lasted 70 years but was often unstable.

Panama in the 1800s

When Venezuela and Ecuador became separate countries, Panama again declared its independence in 1831. This time, General Alzuru was in charge. But his rule was unfair. Colonel Tomás de Herrera led forces against Alzuru, defeated him, and had him executed. Panama then rejoined New Granada.

A religious conflict caused a civil war. In November 1840, Panama, led by General Tomás de Herrera, declared its independence again. It called itself the 'Estado Libre del Istmo' (Free State of the Isthmus). This new state made its own deals with other countries. By March 1841, it had a constitution that allowed it to rejoin New Granada, but only as a federal district. Herrera became the "Superior Chief of State" and then "President." Panama's first republic was free for 13 months before it rejoined New Granada on December 31, 1841.

The union (later called the United States of Colombia and then the Republic of Colombia) continued with help from the USA. In the 1840s, the US and France became interested in building railroads or canals across Central America. It was clear that New Granada was struggling to control Panama. In 1846, the US and New Granada signed the Bidlack Mallarino Treaty. This gave the US rights to cross Panama and, importantly, the power to use its military to keep the area neutral.

The world's first transcontinental railroad, the Panama Railway, was finished in 1855. It crossed Panama from Colón to Panama City. In April 1856, a fight called the Watermelon Riot happened. A group of Panamanians attacked American travelers after an American stole a watermelon. This led the US to send troops in September 1856 to protect the railroad. This was the first of many times the US sent troops to Panama.

The US often used its troops to stop independence movements and unrest in Panama.

Under new federalist constitutions in 1858 and 1863, Panama and other states gained a lot of freedom in how they governed themselves. This led to a chaotic situation until Colombia became more centralized again in 1886.

After independence, a small group of wealthy families controlled politics in Panama. Even today, a few families have a lot of economic and social power. The term rabiblanco is used to describe these usually Caucasian elite families.

In 1852, Panama started using trial by jury in criminal cases. Thirty years after slavery was abolished, it was finally ended and enforced in Panama.

The Panama Canal Story

Panama's history has always been about trade across its narrow land. People dreamed of a canal to replace the difficult land route. In 1519, Spain built a paved road connecting the oceans. By 1534, the Chagres River was made deeper, helping ships travel two-thirds of the way.

French Efforts to Build a Canal

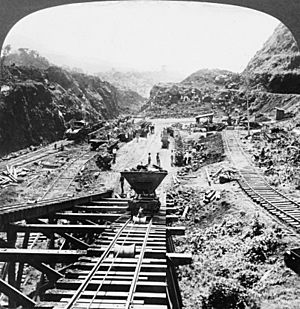

In 1882, Ferdinand de Lesseps started working on a canal. But by 1889, the project failed. There were huge engineering problems like landslides and mud, and many workers got sick. The company went bankrupt. A new company was formed in 1894 to try and get some money back. Old French machinery from this time could still be seen in Panama until recently.

US Involvement in the Canal

US President Theodore Roosevelt convinced the US Congress to take over the abandoned canal project in 1902. At this time, Colombia was in a civil war. During the war, Panamanian groups tried to gain control of Panama several times. These attempts were stopped by Colombian and US forces working together.

The Roosevelt government offered Colombia $10 million and $250,000 yearly to control the canal. Negotiations went well at first, and the US got what it wanted in the Hay–Herrán Treaty. But the Colombian government was unhappy with the treaty and refused to approve it, demanding more money. By September 1903, talks had almost completely stopped. The US then changed its plan.

The US was supposed to pay $40 million to the French company that had tried to build the canal. Colombia's rejection meant these French investors might lose everything. So, the French company's main lobbyist and a major owner, Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla, took action. He met with Manuel Amador Guerrero, the leader of the Panamanian Independence movement. Bunau-Varilla gave Amador a $100,000 check to help fund a new Panamanian revolt. In return, Bunau-Varilla would become Panama's representative in Washington.

Bunau-Varilla arranged for the Panama City fire department to start a revolution against Colombia on November 3, 1903. The US Navy ship USS Nashville was sent to Colón, where 474 Colombian soldiers had landed to stop the rebellion. The US commander prevented the Colombians from taking the train to Panama City. On November 13, 1903, the US officially recognized Panama as a country.

Less than three weeks later, on November 18, 1903, the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty was signed. It was between Philippe Bunau-Varilla (who was now Panama's ambassador to the US) and US Secretary of State John Hay. This treaty allowed the US to build the canal and gave the US control over a 10-mile wide (16 km) and 50-mile long (80 km) strip of land around the Panama Canal Zone. In this zone, the US would build, manage, protect, and defend the canal "forever."

President Roosevelt explained the US role in many speeches. He said Colombia had rejected his offers and had never been able to keep order in Panama. He listed 53 times the US military had intervened in Panama since 1850. He argued that only US help had kept Colombia connected to Panama.

Roosevelt's speeches made it clear that the US decided to break its old treaty with Colombia. Instead of helping Colombia with its internal problems, the US helped Panama separate. So, the US only followed the part of the treaty that helped its own interests.

It's a common mistake to call the 1903 events "Panama's independence from Colombia." Panamanians don't see themselves as former Colombians. They celebrate their independence from Spain on November 28, 1821, and their separation from Colombia on November 3, 1903, which they call "Separation Day."

Reactions to the Treaty

In the US, people generally liked the treaty because it meant the canal would be built. But in Panama, reactions were mixed. The new Panamanian government, led by Manuel Amador, was happy to be independent from Colombia. However, they also worried that the US could easily control them. They had told their ambassador, Bunau-Varilla, not to make any deals that would hurt Panama's new freedom or sign a canal treaty without asking them. He ignored both orders. Still, the Panamanian government approved the treaty because they feared what might happen if they didn't.

By the time the Canal opened in 1914, many Panamanians still questioned if the treaty was fair. The US presence in Panama was a big issue for decades. Even changes to the treaty in 1936 and 1955 didn't fully solve the problem. The controversy continued until the US agreed to give full control of the Canal Zone to Panama in the 1977 Torrijos-Carter Treaties.

Building the Canal

The Panama Canal was built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers between 1904 and 1914. This 83-kilometer (50-mile) lock canal is seen as one of the world's greatest engineering achievements. In 1909, Colombia tried to sign a treaty recognizing Panama's independence, but it wasn't approved. Negotiations continued until a new treaty was signed in 1921, formally accepting Panama's independence.

Roosevelt's policy of "walk softly and carry a big stick" and the early segregation in the Canal Zone have been criticized. However, the canal project brought many good changes to Panama. To make the area healthy for workers, engineers built systems for clean water, sewage, and trash.

The Canal Zone's towns had very high standards for construction, transportation, and landscaping. Dr. William Gorgas used methods developed by Cuban doctor Carlos Finley to get rid of yellow fever between 1902 and 1905. Gorgas's work in making the Canal Zone and the cities of Panama and Colon clean made him famous worldwide.

The Panama Canal, the land around it, and the remaining US military bases were given to Panama on December 31, 1999. This was according to the Torrijos-Carter Treaties.

Military Rule and Changes

From 1903 to 1968, Panama was a republic mostly controlled by a few wealthy families. In the 1950s, the Panamanian military started to challenge these families' power. On January 9, 1964, the Martyrs' Day riots increased tensions between Panama and the US over the Canal Zone. Twenty Panamanians were killed, and 500 were wounded. Four US soldiers also died.

In October 1968, Dr. Arnulfo Arias Madrid was elected president for the third time. But the National Guard removed him from office after only 10 days. A military government was set up, and the commander of the National Guard, Brig. Gen. Omar Torrijos, became the main leader in Panama. Torrijos started programs to help ordinary people. He opened schools, created jobs, and gave farmland to people. He also pushed for higher wages for workers and redistributed land. His policies helped create a middle class and gave a voice to native communities.

On September 7, 1977, the Torrijos–Carter Treaties were signed by Omar Torrijos and US President Jimmy Carter. These treaties arranged for the full transfer of the Canal and 14 US army bases from the US to Panama by 1999. They also allowed the US to intervene militarily if needed. Parts of the Canal Zone and responsibility for the Canal were gradually handed over in the years leading up to 1999.

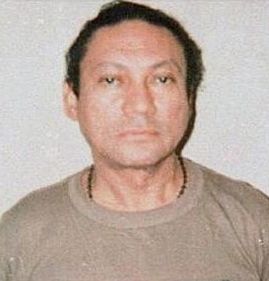

Manuel Noriega's Time (1983–1989)

Torrijos died in a mysterious plane crash on July 31, 1981. Some people believe he was assassinated. Torrijos's death changed Panama's politics, but the military still had a lot of power. Even though changes were made in 1983 to limit the military's role, the Panama Defense Forces (PDF) continued to control the government. General Manuel Noriega took firm control of both the PDF and the civilian government. He created groups called Dignity Battalions to stop people who disagreed with him.

Even though Noriega secretly worked with US President Ronald Reagan on his war in Nicaragua, relations between the US and Panama got worse in the 1980s. Because of problems in Panama and an attack on the US embassy, the US stopped giving money and military help to Panama in 1987. Tensions grew in 1988. The US froze Panamanian government money in US banks and stopped payments for using the canal. This caused big problems in Panama.

The national elections in May 1989 were full of problems. Guillermo Endara won by a large margin over Noriega. But Noriega's government canceled the election, saying the US had interfered too much. They then started to crack down on opposition.

Outside observers, including the Catholic Church and Jimmy Carter, confirmed that Endara had won the election. The US asked the Organization of American States to help, but they couldn't get Noriega to leave. The US then started sending thousands of troops to its bases in the Canal Zone.

US Invasion of Panama (1989)

By late 1989, Noriega's government was barely holding on. On December 20, US troops began an invasion of Panama. This operation, called "Just Cause," quickly achieved its goals, and troops started leaving on December 27. The US had to return control of the Canal to Panama on January 1, as agreed in a treaty. Endara was sworn in as President at a US military base on the day of the invasion. Noriega spent 40 years in prison before he died in 2017.

The US estimated that 202 civilians died, while the UN estimated 500, and Americas Watch said 300.

After the invasion, US President George H. W. Bush announced a billion dollars in aid for Panama. Critics said about half of this aid actually helped American businesses, not just Panama.

Panama After Noriega (1989–Present)

On the morning of December 20, 1989, just hours after the invasion began, Guillermo Endara was sworn in as president of Panama at a US military base. On December 27, Panama's Electoral Tribunal confirmed Endara's victory in the May 1989 election.

President Endara led a government with four parties. He promised to help Panama's economy recover, change the military into a police force under civilian control, and strengthen democracy. During his five years, his government tried hard to meet people's high hopes. The new police force was much better than the old one but still struggled to stop crime. After an election watched by international observers, Ernesto Pérez Balladares became President on September 1, 1994.

Pérez Balladares was from the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD), which had been linked to the military government. He worked to improve the party's image, focusing on its roots with Torrijos rather than Noriega. He won the election with 33% of the vote because other parties couldn't agree on a single candidate. His government made economic changes and worked closely with the US on the Canal treaties.

On May 2, 1999, Mireya Moscoso, the wife of former President Arnulfo Arias Madrid, defeated Martín Torrijos, the son of the late leader. The elections were considered fair. Moscoso took office on September 1, 1999.

During her time as president, Moscoso worked to improve social programs, especially for children and young people. Education programs were also important. She also focused on trade deals with other countries. Moscoso's government successfully managed the transfer of the Panama Canal and did a good job running it.

The Panamanian government made laws against money laundering stronger. The government protected intellectual property rights and made important trade deals with the US. Moscoso's government strongly supported the United States in fighting international terrorism.

In 2004, Martín Torrijos ran for president again and won the election. In 2009, Ricardo Martinelli, a conservative businessman, won the presidential election by a lot. Five years later, Juan Carlos Varela won the 2014 election and became president. In July 2019, Laurentino “Nito” Cortizo of the Democratic Revolution Party (PRD) became the new President of Panama, after winning the May 2019 presidential election.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Panamá para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Panamá para niños

- List of heads of state of Panama

- Politics of Panama

- List of Royal Governors of Panama

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |