Manila galleon facts for kids

| Native name | Galyon ng Maynila |

|---|---|

| English name | Manila Galleon |

| Duration | From 1565 to 1815 (250 years) |

| Venue | Between Manila and Acapulco |

| Location | New Spain (Spanish Empire) (Current Philippines and Mexico) |

| Motive | Trading maritime route from East Indies to the Americas |

| Organised by | Spanish Crown |

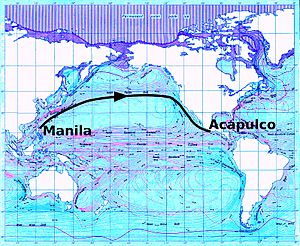

The Manila Galleons (Spanish: Galeón de Manila; Filipino: Galyon ng Maynila) were large Spanish trading ships. For 250 years, they connected the Captaincy General of the Philippines with Mexico across the Pacific Ocean. These ships made one or two round trips each year between the ports of Acapulco and Manila. Both cities were part of New Spain at the time.

The name of the galleon often changed depending on the city it sailed from. The term Manila galleon also refers to the trade route itself. This important route lasted from 1565 to 1815.

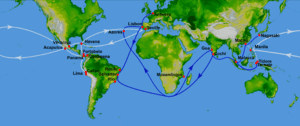

For two and a half centuries, the Manila galleons carried valuable goods across the Pacific. They brought luxury goods like spices and porcelain to the Americas. In return, they took silver from the New World back to Asia. This trade route also helped different cultures mix, shaping the identity of the countries involved.

In New Spain (Mexico), the Manila galleons were sometimes called La Nao de la China ("The China Ship"). This was because they mostly carried Chinese goods that were shipped from Manila.

The Manila galleon trade began in 1565. This happened after an Augustinian friar and navigator named Andrés de Urdaneta found a way to sail back from the Philippines to Mexico. This return route was called the tornaviaje. Urdaneta and Alonso de Arellano successfully completed the first round trips that year. The trade using "Urdaneta's route" continued until 1815, when the Mexican War of Independence started.

Today, the Philippines and Mexico are working together to get the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade Route recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Spain is also helping with this effort. Spain has also suggested that old records about the galleons be added to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.

Contents

History of the Galleon Trade

Discovering the Pacific Route

In 1521, a Spanish expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan sailed west across the Pacific. They used the westward trade winds to help them. This expedition found the Mariana Islands and the Philippines, claiming them for Spain. Even though Magellan died there, one of his ships, the Victoria, made it back to Spain by continuing to sail west.

To settle and trade with these new islands from the Americas, the Spanish needed a way to sail back east. This was much harder. Several attempts failed. In 1529, Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón tried sailing east from the Philippines but couldn't find the eastward-blowing winds (called "westerlies") across the Pacific. Bernardo de la Torre also failed in 1543.

The Manila–Acapulco galleon trade finally started when Spanish navigators Alonso de Arellano and Andrés de Urdaneta found the eastward return route in 1565. Urdaneta was part of an expedition to conquer the Philippines in 1564. He was given the important job of finding a way back.

Urdaneta thought that the Pacific's trade winds might move in a circle like the Atlantic winds. So, he sailed far north, all the way to the 38th parallel north, off the east coast of Japan. There, he caught the strong westerlies that carried his ship back across the Pacific. His ship completed the eastward journey in 129 days. This amazing trip officially opened the Manila galleon trade route.

Urdaneta's ship, the San Pedro, reached the west coast of North America near Santa Catalina Island, California. It then followed the coastline south to San Blas and later to Acapulco, arriving on October 8, 1565. Many of his crew died on the long journey because they didn't have enough supplies. Arellano, who took a slightly more southerly route, had already arrived.

By the 1700s, sailors learned that they didn't need to go so far north when nearing the North American coast. Galleon navigators stayed away from the rocky and foggy northern California coast. They usually landed somewhere between Point Conception and Cape San Lucas. These ships were mainly for trade, not for exploring new lands.

Later, in 1769, the Portolá expedition helped by setting up ports at San Diego and Monterey. Monterey became an important stop for returning Manila galleons.

Trade and Goods

Trade with Ming China through Manila brought a lot of money to the Spanish Empire. It was also a main source of income for Spanish settlers in the Philippines. The large ships used for this trade were built by Filipino artisans.

At first, two or more ships sailed each year from each port. The Manila trade became so profitable that merchants in Seville, Spain, asked King Philip II of Spain to protect their trade. So, in 1593, a rule was made: only two ships could sail each year from either port. One ship was kept in reserve in Acapulco and one in Manila. An "armada" (armed escort) of galleons was also approved. Because of these rules, illegal trading and hiding goods became common.

Merchants from Fujian, China, mainly supplied the galleon trade. They traveled to Manila to sell spices, porcelain, ivory, lacquerware, silk cloth, and other valuable items to the Spanish. The goods on board changed each trip but often included items from all over Asia. These included jade, wax, gunpowder, and silk from China. Amber, cotton, and rugs came from India. Spices came from Indonesia and Malaysia. Japan provided fans, chests, screens, porcelain, and lacquerware.

The galleons carried these goods to be sold in the Americas, especially in New Spain (Mexico) and Peru. They were also sold in European markets. Trade in East Asia mostly used silver because Ming China used silver ingots as money. So, goods were mainly bought with silver mined from New Spain and Potosí.

About 80% of the goods shipped back from Acapulco to Manila came from the Americas. These included silver, cochineal (a dye), seeds, sweet potato, tobacco, chickpeas, chocolate, cocoa, watermelon, and vine and fig trees. The other 20% were goods from Europe and North Africa, like wine, olive oil, and metal items such as weapons.

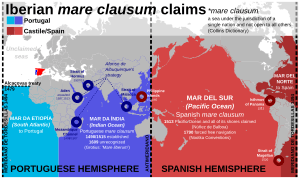

This Pacific route was important because it avoided the trip west across the Indian Ocean and around the Cape of Good Hope. That route was controlled by Portugal according to the Treaty of Tordesillas. The galleon route also avoided ports controlled by other powerful countries like Portugal and the Netherlands.

It took at least four months to sail across the Pacific Ocean from Manila to Acapulco. The galleons were the main link between the Philippines and the capital of New Spain, Mexico City, and then to Spain itself. Many of the "Kastilas" (Spaniards) in the Philippines were actually of Mexican descent. The Hispanic culture of the Philippines is quite similar to Mexican culture. Soldiers and settlers from Mexico and Peru were also gathered in Acapulco before being sent to the presidios (forts) in the Philippines.

In Manila, people prayed to the Virgin Nuestra Señora de la Soledad de Porta Vaga for safe ocean crossings. If a trip was successful, the voyagers would go to a church to give thanks and offer gold and jewels to the Virgin's image. Because of this, the Virgin was called the "Queen of the Galleons".

End of the Galleons

In 1740, the Spanish crown started allowing other ships, called navíos de registro, to travel alone in the Pacific. These ships were more efficient and better at avoiding capture by the Royal Navy.

The Manila-Acapulco galleon trade officially ended in 1815. This was a few years before Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821. After this, the Spanish Crown took direct control of the Philippines, ruling directly from Madrid. Sea travel became much easier in the mid-1800s with the invention of steam-powered ships and the opening of the Suez Canal. These changes reduced the travel time from Spain to the Philippines to just 40 days.

The Galleons Themselves

How They Were Built

Between 1609 and 1616, nine galleons and six galleys were built in shipyards in the Philippines. Each galleon cost about 78,000 pesos and required at least 2,000 trees. Some of the galleons built included the San Juan Bautista, San Marcos, and Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe. From 1729 to 1739, the main job of the Cavite shipyard was to build and equip galleons for the Manila to Acapulco trade route.

Because the route was very profitable but the journey was long, it was important to build the largest possible galleons. These were the biggest European ships known to have been built at that time. In the 1500s, they weighed between 1,700 and 2,000 tons and could carry 300 to 500 passengers. They were built from strong Philippine hardwoods. For example, the Concepción, which sank in 1638, was about 43 to 49 meters (140 to 160 feet) long and weighed about 2,000 tons. The Santísima Trinidad was 51.5 meters (169 feet) long. Most of these ships were built in the Philippines, with only eight built in Mexico.

The Crews

The average age of sailors was 28 or 29, with some older sailors between 40 and 50. Ship pages were children, often orphans or poor kids from the streets of Seville, Mexico, and Manila, who started working at around age 8. Apprentices were older than pages. If they did well, they could become certified sailors by age 20.

Life on board was very tough. Many ships arrived in Manila with most of their crew dead from hunger, disease, and scurvy, especially in the early years. Because of this, Spanish officials in Manila found it hard to find men to crew the ships returning to Acapulco. Many indios (local people) from the Philippines and Southeast Asia made up most of the crew. Other crew members included criminals and people sent from Spain and its colonies. Less than a third of the crew were Spanish, and they usually held the most important jobs on the galleon.

At port, goods were unloaded by dockworkers. Food and supplies were often bought locally. In Acapulco, the arrival of the galleons created seasonal jobs. Dockworkers, often free black men, were paid well for their hard work. Farmers and haciendas (large estates) across Mexico also supplied food and supplies for the long voyages. This helped boost the economy of New Spain.

Shipwrecks and Captures

The wrecks of the Manila galleons are famous, almost as much as the treasure ships in the Caribbean. In 1568, Miguel López de Legazpi's own ship, the San Pablo, was the first Manila galleon to sink on its way to Mexico. Between 1576 and 1798, twenty Manila galleons were lost within the Philippine islands. In 1596, the San Felipe sank in Japan. Its cargo was taken by Japanese authorities, and the crew's actions led to the persecution of Christians.

At least one galleon, likely the Santo Cristo de Burgos, is thought to have sunk off the coast of Oregon in 1693. This event is known as the Beeswax wreck. Local stories from the Tillamook and Clatsop suggest some of the crew survived.

Between 1565 and 1815, Spain owned 108 galleons. Of these, 26 were lost at sea for various reasons. Some galleons were captured by the British. For example, in 1587, the Santa Anna was captured by Thomas Cavendish. In 1743, the Nuestra Senora de la Covadonga was taken by George Anson during his voyage around the world. In 1762, the Nuestra Senora de la Santisima Trinidad was captured by two British ships.

UNESCO Nominations

In 2014, Mexico and the Philippines suggested that the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade Route be nominated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. Spain has supported this idea. Spain also suggested that the historical records about the route, held in the Philippines, Mexico, and Spain, be nominated for the Memory of the World Register.

In 2015, experts met to discuss the trade route's nomination. They talked about Spanish shipyards in Sorsogon, underwater archaeology in the Philippines, and how the route influenced Filipino textiles. They also discussed the tornaviaje (the eastward trip from the Philippines to Mexico) and important historical documents.

In 2017, the Philippines opened the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Museum in Metro Manila. This was an important step towards getting the trade route recognized by UNESCO. In 2018, Mexico reopened its Manila galleon gallery at the Archaeological Museum of Puerto Vallarta.

Images for kids

-

The Selden Map, a merchant map showing trade routes with its epicenter from Quanzhou to Manila and across the Spanish Philippines and across the Far East

See also

In Spanish: Galeón de Manila para niños

In Spanish: Galeón de Manila para niños