George Anson's voyage around the world facts for kids

While Britain was fighting a war with Spain in 1740, a brave leader named George Anson led a group of eight ships. Their secret mission was to cause trouble for Spain's lands in the Pacific Ocean. Anson's journey took him all the way around the world, passing by China. He returned to Britain in 1744. This trip was famous for capturing a rich Spanish ship called the Manila galleon. But it was also very sad because many sailors died from sickness. Out of 1,854 men, only 188 survived. A book about the voyage was published in 1748. It became very popular and is still known as a great adventure story.

Contents

Why the Voyage Happened

In 1739, everyone in Europe knew about the amazing riches Spain got from the New World (the Americas). Huge amounts of silver were sent from Peru. They were carried across Panama and then loaded onto ships at Portobelo to go to Spain. Other ships brought fancy goods from Manila to Acapulco. From there, they went to Vera Cruz and were loaded with Mexican silver. Spain's lands in the Caribbean also provided sugar, tobacco, and spices.

Britain had a deal that allowed one trading ship per year to go to Spanish lands. But many British traders, especially from Jamaica, smuggled goods to avoid taxes. Spain tried to stop them. After many problems, old rivalries grew, leading to the War of Jenkins' Ear.

Many plans were made to attack Spanish lands. One British leader, Edward Vernon, captured Portobelo with just six ships. George Anson was given a second group of ships. He was told to sail around Cape Horn with six warships and 500 soldiers. His orders were to capture Callao (a port in Peru) and maybe even Lima, the capital. He was also supposed to capture Panama and its treasures, seize the galleon from Acapulco, and even start a revolt in Peru against Spain.

Anson's orders were very difficult, partly because of a conflict of interest. Two agents from a trading company, Hubert Tassell and Henry Hutchison, suggested these attacks. They knew a lot about the area and would gain money if Britain could trade there. Anson's ships even carried £15,000 worth of goods to trade.

The Ships and the Crew

Anson's group of ships was based in Portsmouth. It had six warships:

- Centurion (the main ship, with 60 guns and 400 men)

- Gloucester (50 guns, 300 men)

- Severn (50 guns, 300 men)

- Pearl (40 guns, 250 men)

- Wager (24 guns, 120 men)

- Tryal (8 guns, 70 men)

Two merchant ships, Anna and Industry, carried extra supplies.

The plan to have 500 soldiers was a bit of a joke. No regular soldiers were available. Instead, 500 "invalids" were to be taken from a hospital. "Invalids" meant soldiers who were too sick, wounded, or old for normal duty. Many of them ran away when they heard about the trip. Only 259 came aboard, and many were on stretchers. To make up for the missing men, new marines were ordered to join. But most of them had never even learned how to fire a gun!

Setting Sail

The ships were as ready as they could be by mid-August. But strong winds kept them in the harbor. Before heading to South America, Anson had to escort a huge group of transport and merchant ships out of the English Channel. Their first try to leave was stopped when ships crashed into each other. Finally, the group sailed from Spithead on September 18, 1740, leading a convoy of 152 ships.

Sadly, because of the long delays, French spies found out about the trip. They told Spain. In response, Spain sent five warships under Admiral Pizarro. They waited near Portuguese Madeira, which was neutral territory and Anson's first planned stop.

The Long Voyage

Anson's ships reached Madeira on October 25, 1740. The trip took four weeks longer than usual. Portuguese officials said that warships, probably Spanish, had been seen nearby. Anson sent a boat to check, but it didn't see them. They quickly loaded fresh food and water. The ships left without trouble on November 3. If they had met Pizarro's ships, the trip would likely have ended. Anson's ships were so full of supplies that their guns couldn't be used properly.

After three days at sea, transferring supplies, the Industry turned back. By now, food was rotting, and the ships were full of flies. They desperately needed more air below deck. Usually, they would open the gun ports, but the ships were too low in the water from all the supplies. So, six air holes were cut into each ship.

This was part of a bigger problem that caused terrible results. With the regular crew, the ships were already crowded. But the invalids and marines added about 25% more men. They had to stay below deck most of the time. Typhus, or "ship fever," spread by body lice, thrived in the hot, crowded, and dirty conditions. After two months at sea, this disease and dysentery quickly spread through the crews.

The ships reached Ilha de Santa Catarina (St Catherine's), an island off the coast of Brazil, on December 21. The sick men were sent ashore. Eighty men from Centurion alone went. Then, a thorough cleaning began. Below-deck areas were scrubbed, fires were lit to kill rats and bugs, and everything was washed with vinegar.

Anson wanted to stay only long enough for wood, water, and food. But the main mast of Tryal needed repairs that took almost a month. Meanwhile, the men on shore in tents were exposed to mosquitoes and malaria. Even though 28 men from Centurion died in port, the number of sick men taken back aboard when they left on January 18, 1741, increased from 80 to 96. Many fruits and vegetables were available, but it's unclear how much actually made it onto the ships. The governor of the island secretly told Spanish Buenos Aires that Anson was there. Admiral Pizarro's ships had arrived in Buenos Aires. Pizarro immediately sailed south to get around Cape Horn before the British.

Anson sailed on January 18, 1741. He planned to stop at Puerto San Julián, where there were supposedly lots of salt. Four days later, in a storm, Tryal's repaired mast broke. Gloucester had to tow it. During the same storm, Pearl got separated. Its captain died, and First Lieutenant Sampson Salt took command. Sampson then saw five ships. The first one had English flags, but at the last moment, he realized they were Spanish! The crew quickly threw everything they didn't need overboard and raised more sails. The Spanish ships didn't chase, thinking Pearl was heading for shallow water. But it was just fish, not rocks. Pearl escaped as darkness fell.

Even though the Spanish ships were known to be nearby, Anson's group had to stop at St Julian. They found no trees, fresh water, or much salt. Tryal's broken mast was replaced with a spare. This made her rigging smaller but probably helped her survive the terrible storms ahead. The ships reached Strait of Le Maire, the entrance to the path around Cape Horn, on March 7, 1741. The weather was unusually good, but soon it turned into a violent storm from the south.

While fighting strong winds and huge waves, with a crew already weak from typhus and dysentery, scurvy broke out. Scurvy is a terrible disease caused by not getting enough vitamin C. Hundreds of men died from disease during and right after battling around Cape Horn. In one amazing case, a man who had been wounded 50 years earlier found his old wounds reopened and a broken bone fractured again!

In early April, the ships headed north, thinking they were 300 miles west of land. But ships at that time had to guess their east-west position. They couldn't account for unknown ocean currents. So, on the night of April 13-14, the crew of the Anna were shocked to see the cliffs of Cape Noir just 2 miles away! They fired cannons and lit lamps to warn the others. They barely managed to sail back out to sea. There was great worry that Severn and Pearl were already lost, as they hadn't been seen since the 10th.

Another storm hit just as the Wager disappeared. On April 24, both Centurion and Gloucester reported that all their sails were torn. But the crew was too few and too weak to fix them until the next day. By then, the ships were scattered. Anson's instructions included three meeting points if the ships got separated. Centurion reached the first, Socorro, on May 8. After waiting two weeks and seeing no other ships, Anson decided to sail for Juan Fernandez, the third meeting point.

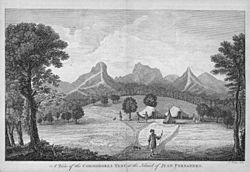

However, Anson's maps were wrong. Juan Fernandez was much further west than shown. Anson, unsure of his maps, headed east and soon saw the coast of Chile. Turning back west, it took nine days to reach the area he had left. During this time, 70–80 more men died. Juan Fernandez was finally seen on June 9. But by now, only eight men and a few officers were strong enough to work the ship. They were too weak to lift the anchor the next morning but were lucky to be blown free by a sudden gust of wind. As they sailed into the bay, they were upset to find no other ships. But then they saw the tiny Tryal approaching. Of its 86 crew and marines, 46 had died. Only the captain, his lieutenant, and three sailors could stand on deck. Those still able worked hard to get the sick men ashore.

Pictures from Anson's Voyage:

-

Anson's tent at Robinson Crusoe Island

Given how many men had died on Centurion and Tryal, it seemed likely that the crews of the other ships would all be dead if they couldn't reach Juan Fernandez soon. On June 21, a ship was seen with only one sail, looking like it was in trouble. It took six more days to identify it as Gloucester. A longboat was sent to meet the ship, but they couldn't get it into the bay. The ship was then blown out to sea. It wasn't until July 23 that Gloucester finally made it to anchor. Since leaving Port St Julian, 254 men had died, leaving 92 men, most very weak from scurvy. Fresh greens and fish helped some recover quickly, but others were too weak and died ashore.

Amazingly, the Anna was seen on August 16. She sailed into Cumberland Bay without much trouble. After losing sight of the other ships on April 24, she had tried to reach the meeting point at Socorro and had been blown ashore. Just when all hope seemed lost, they saw the entrance to a harbor. They took refuge there for two months, making repairs and letting the crew recover. The harbor had good fresh water, wild greens, and game. Because of the good food and fewer crew members, the Anna's crew was much healthier than those on the warships. However, after arriving at Juan Fernandez, a survey showed she was too badly damaged to repair. So Anson had the ship broken up, and her crew moved to Gloucester. Anson prepared to sail in September 1741. He took a count and found that of the original 961 men who left Britain on Centurion, Gloucester, and Tryal, 626 (about two-thirds) had died.

The Missing Ships

Severn and Pearl lost sight of the other ships during the night of April 10, 1741. The captains later said they had severe problems with sickness and ship damage. Anson had told them their situation was no different from the others.

The two ships headed north together, trying to rejoin the group. But on the 13th, they also saw land, which they thought was hundreds of miles behind them. Luckily, they saw land in daylight, so they had more warning. As fog came down, and not knowing what happened to the other ships, Severn and Pearl headed west to get more space at sea. The officers agreed that unless the winds became favorable, they would go back around Cape Horn to safety. Then on the 17th, strong winds from the north-west pushed them back toward land. Lookouts thought they saw land. To save the ships and crew, the order was given to turn south and east and retreat around Cape Horn. By the time Pearl reached Rio de Janeiro on June 6, 158 of her crew had died. Of the rest, 114 were too sick to work, leaving just 30 men and boys to sail the ship. This doesn't include the invalids and marines, nearly all of whom died.

After a month in Rio, the captain of Pearl wanted to try again to reach the Pacific. But the senior officer, Captain Legge of Severn, said no. He said both ships still didn't have enough healthy men. The two ships left Rio in December 1741 and headed for England.

The Wager Mutiny

The Wager was more of a cargo ship than a warship. Even though only Tryal was smaller, she carried the most invalids and marines (142 men, more than her crew of 106). She also carried many supplies for the other ships.

David Cheap was her third captain. He had been sick for much of the voyage. He was below deck, sick in his cabin, when the damaged ship lost sight of the others after barely escaping Cape Noir. He ordered the ship to head for the first meeting point, Socorro Island. His lieutenant and the gunner argued that it was too dangerous to approach land in a damaged ship with only 12 men fit for duty. They thought they should head for Juan Fernandez in the open ocean instead. But Cheap overruled them.

On May 13, 1741, the carpenter thought he saw land to the west. This seemed unlikely, as the mainland was to the east. But they had no proper map, so the report was ignored. They soon realized they had sailed into a large bay with land blocking their way north. After struggling to turn the ship with so few men, a large wave hit. Captain Cheap fell down a ladder and dislocated his shoulder. The surgeon gave him medicine for the pain, and he slept below. Instead of taking command, the lieutenant started drinking and also disappeared below. The storm lashed the ship, and it crashed onto rocks at 4 AM. For the next few hours, it lurched from one rock to another. Then, just before sinking, it got completely stuck. At this point, all discipline broke down. The crew helped themselves to alcohol and weapons. The ship's boats were still working, and 140 men made it to the beach of what became known as Wager Island. Cheap was carried ashore. He tried to stay in control, but most blamed him for losing the ship.

About 100 men remained alive on the beach with limited food saved from the wreck. They had little shelter from the terrible winter winds and rain. Their only hope was the 38-foot longboat, a 30-foot cutter, and two smaller boats. The carpenter made the longboat longer, to 50 feet, and added a deck so most, but not all, could fit.

While the work was happening, arguments started about where to go. A slow mutiny began. Cheap still insisted on sailing north to uninhabited Socorro, hoping to find Anson there. Valdivia was 600 miles north, but as a Spanish town, they wouldn't find help there. The gunner, John Bulkeley, read about the dangerous Strait of Magellan 400 miles to the south. He thought it was their only good option, as they could then sail north to Brazil. He got 45 others to sign a paper agreeing to his plan. By the time the longboat was ready on October 9, 1741, Cheap still hadn't made a final decision. So Bulkeley had him arrested for murder and tied him up.

Four days later, the newly named Speedwell, now like a schooner, sailed south with 59 men. It was followed by the cutter with 12 men, a 'barge' with 10, and another small boat with Cheap and a few others. It seems Bulkeley wanted Cheap to be left behind in the smallest boat. About a dozen men had run away from the camp and were left on the island. After making only a few miles in two days, a sail on the cutter tore. The men on the barge were sent to get canvas from the camp. When they returned, they chose to follow Captain Cheap. The larger boats again headed south, only to lose the cutter a few days later in a storm. There wasn't room on the Speedwell, so 10 men were put ashore. Without a small boat, the only way to get food was to swim through the icy water. Soon, those who were too weak or couldn't swim started dying. With arguments over directions, strong currents, rain, and fog, it took a month to reach the Atlantic.

The Speedwell came close to shore on January 14, 1742, at Freshwater Bay. Those who swam ashore found fresh water and seals. Eight of them were upset to see the boat leaving without them. They later accused Bulkeley of abandoning them to save supplies. Bulkeley, Baynes, and 31 others sailed north, reaching Portuguese waters on January 28. Three men died during the journey, and the rest were very close to death. Eventually, some of the men made their way back to England.

Meanwhile, Captain Cheap had a group of 19 men back at Wager Island after some deserters rejoined the camp. They rowed up the coast but faced constant rain, headwinds, and waves. One night, one of the boats capsized and was swept out to sea. Since they couldn't all fit in the remaining boat, four marines were left ashore. But the winds prevented them from getting around the headland, so they returned to Wager Island in early February 1742. With one death, there were now 13 in the group.

A local Chono Indian agreed to guide the men up the coast to Chiloé Island in exchange for the boat. Two men died. After burying them, the six sailors rowed off in the boat and were never seen again. Cheap, Hamilton, Byron, Campbell, and the dying Elliot were on shore looking for food. The Indian then agreed to take the remaining four by canoe for their last possession, a musket. Eventually, they were captured by the Spanish. Luckily, the Spaniards treated them well. They were taken to the capital of Santiago and later released. They heard that Anson had treated his prisoners well, so this kindness was returned.

The four men stayed in Santiago until late 1744. They were offered passage on a French ship going to Spain. Campbell chose not to go. He took a mule across the Andes mountains and joined Admiral Pizarro in Montevideo. There, he found Isaac Morris and the two sailors who had been abandoned in Freshwater Bay. After more time in prison in Spain, Campbell reached Britain in May 1746, followed by the other three two months later.

Twenty-nine crew members plus seven marines from the Wager made it back to England.

Attacks in Spanish America

By September 1741, back at Juan Fernandez, most of Anson's men were recovering. As their health improved, they started repairing the ships as best they could. Anson wondered what to do next. His force was much smaller, and he hadn't heard any news for nine months. He didn't know what had happened to Pizarro's ships.

While thinking about attacking Panama, a single ship was sighted on September 8. It sailed past the island. Anson thought it was Spanish, so he got Centurion ready and chased it. But it disappeared. They kept searching for two more days. Just as they were about to give up, another ship was spotted coming right towards them. It turned out to be a lightly armed merchant ship. After Centurion fired four shots, it surrendered. The cargo of Nuestra Señora del Monte Carmelo (called Carmelo) wasn't very interesting, but the passengers had £18,000 in silver! Even more valuable was the information they found in documents. Spain was still at war with Britain. There was no hope of joining friendly forces for a combined attack on Panama. But there was no immediate danger from Pizarro. His ships had suffered even more terribly trying to get around Cape Horn.

Pizarro's ships had set out with only four months of food. They were hit by terrible storms after rounding the Horn and were pushed backward. The British and Spanish ships must have passed each other, but both sides were focused on survival and couldn't see well. One of Pizarro's ships sank without a trace. On the other ships, crews began to starve. Pizarro's main ship and another made it back to the River Plate with only half the crew alive. On another ship, only 58 out of 450 men survived. One ship started leaking and lost all its masts. Fortunately, the wind blew it north, and it ran aground near St. Catherine's.

When Pizarro arrived in Buenos Aires, he sent a message to Peru, warning them about Anson. In response, four armed ships were sent from Callao with orders to kill, not capture. Three were stationed off Concepción, and the fourth went to Juan Fernandez. They gave up waiting in early June, thinking Anson's ships were lost or had gone elsewhere. Anson's wrong map actually saved his ships! The nine days he wasted trying to find the island delayed his arrival until after the Spanish ship had left. Also, the ships from Callao had been badly damaged by storms and would be in port for another two months. So, there were no Spanish ships looking for them. Anson's ships could now capture unsuspecting merchant vessels along the coast. Gloucester was sent north to hunt near Paita.

Centurion, Carmelo, and Tryal waited off Valparaiso. Tryal captured the Arranzazu, an unarmed merchant ship three times her size. It had £5,000 in silver. However, Tryal was badly damaged, so her guns were moved to the captured ship, and Tryal was allowed to sink. Centurion captured the Santa Teresa de Jesus. Its cargo was almost worthless, but the passengers included three women. Anson wanted to show he was a disciplined officer, not a pirate. So, he treated his prisoners well, giving the women a guard and letting them keep their cabins. Then, the Nuestra Señora de Carmin was seized. An Irish sailor on board revealed that Gloucester had been seen, and the authorities had been warned.

With their cover blown, Anson decided to attack Paita immediately. He hoped to capture treasure that was to be shipped to Mexico the next day. The town was small and not well defended. But with limited forces, Anson couldn't hope to conquer any major Spanish settlements. Sixty men went ashore at night in the ships' boats and took the town with hardly any shots fired by the Spanish. Most residents simply ran away to a hill. Anson's men stayed in town for three days, taking the contents of the customs house to the ships, along with livestock for food. On the way out, Anson ordered the prisoners sent ashore and the town burned, except for two churches. One Spanish ship in the harbor was towed away, and the rest were sunk. The prize money came to £30,000. Meanwhile, Gloucester had captured two small ships, getting another £19,000.

The ships then set off toward Acapulco, hoping to intercept the galleon from Manila. It would be two months before it arrived. Both Centurion and Gloucester were towing captured ships, and the winds were against them. With water running low, they stopped at Quibo Island. They also caught giant turtles for food, keeping some alive. Because of good food since leaving Juan Fernandez seven months earlier, only two crew members had died.

On January 26, 1742, they reached what they thought was Acapulco's latitude. They turned east and saw a light in the distance. Centurion and Gloucester chased it, thinking it was the galleon. Dawn showed it was just a fire on a mountain. Anson needed to know if the galleon was in port. Acapulco was nowhere in sight. So, keeping the ships far out at sea, he sent one of the ship's boats to search for the port and see if the ship had arrived. After five days, they returned, unable to even find the port. After sailing further along the coast, the boat was sent out again. This time, they found Acapulco and captured three fishermen. The fishermen confirmed that the galleon had arrived three weeks earlier. But the outbound galleon, loaded with silver, was to sail on March 3, in two weeks. It had a crew of 400 and 58 guns.

The plan was for Centurion and Gloucester to attack. Anson's men were gathered on these ships, helped by slaves taken from the Spanish. These slaves were trained to use the guns and promised their freedom. The ships would stay far offshore during the day to avoid being seen. But they would come close at night in case the galleon tried to escape in the dark. Nothing happened. The Spanish had seen the ship's boat along the coast. They decided not to send the galleon, rightly guessing a trap had been set. There was no hope of attacking the well-defended city. So Anson gave up his frustrating wait in early April as water was dangerously low. He headed north-east to Zihuatanejo, where William Dampier had reported good water. He left seven men in a small boat on patrol outside Acapulco, just in case the galleon sailed. Getting water proved much harder than expected. The river had changed since Dampier's visit in 1685. The men had to walk half a mile inland to find water that was barely good enough.

Since the Spanish were now on alert, it was clear that the way home would be by way of China. They would go to the Portuguese colony at Macau or further up the river to Canton, a base for the English East India Company. Before leaving, Anson had to decide what to do with the captured ships. He had already decided to destroy two of them. Because of the severe shortage of men on Centurion and Gloucester, he decided he had no choice but to also get rid of the Arranzazu, even though it was a good ship. He transferred her men to his own ships.

The small patrol boat had not returned. So Anson sailed back toward Acapulco, hoping to find his men. He concluded they had been captured. He sent six Spanish prisoners ashore in a small boat with a note. It said he would release the rest if his men were set free. On the third day of waiting, the patrol boat appeared, but not from the harbor. The crew was in very poor health. They hadn't been able to land for water and suffered from severe sunburn after six weeks in an open boat. When they arrived, Anson sent 57 of his prisoners ashore, including all the Spaniards. But he kept 43 non-Spaniards. On May 6, 1742, they headed west into the Pacific.

Crossing the Pacific

Based on earlier stories, Anson expected the Pacific crossing to be easy, taking about two months. Other travelers had dropped south from Acapulco to catch the trade winds that blew constantly west. However, none of them had left in May. By then, the good winds had moved further north. Centurion and Gloucester wasted seven weeks in constant heat and light winds, or no wind at all. They went as far south as 6°40'N before giving up and heading north again. Normally, such a delay would be annoying. But with ships and crew in poor condition, disaster soon happened. The front mast of Centurion split just days out from Acapulco. Gloucester lost its mainmast in mid-June. Even with quick repairs, she was much slower. Scurvy broke out first among the prisoners, and then in late June, among the regular crew members.

During July, Gloucester lost most of its remaining ropes and sails. A large leak opened. By August 13, the water inside was seven feet deep despite constant pumping. Captain Mitchell sent a distress signal to Anson. Anson first thought his own ship, Centurion, was also in danger of sinking from leaks. However, when he heard the full details, Anson saw there was no choice but to save whatever they could from Gloucester (mostly the captured silver). Then, they transferred the crew and set the ship on fire. This was to make sure the empty ship didn't drift to Spanish-held Guam. Eight to ten men were dying every day. The leak became so bad that even Anson had to take his turn at the pump. It was now a race to find land, even Guam, before the ship sank. Tinian Island, north and east of Guam, was sighted on August 23. But it took four days to find a safe place to anchor. Anson raised a Spanish flag, hoping for a better welcome. A small boat with four native people and one Spaniard came out to meet them. Luckily, they were the only ones on the island. So Centurion came ashore and anchored. The sick were brought to land, 128 in total. Anson and the boat crew helped, but 21 died during the landing or right after.

The island was a beautiful tropical paradise. It had lots of fruit and other edible plants near the beach. There was also fresh water and cattle, which had been brought there for the Spanish soldiers on Guam. Within just a few days, the men showed clear signs of getting better. The breadfruit tree was especially helpful. Its fruit is full of starch. When boiled and baked, it tastes like a mix between potato and bread. The high praise for it from earlier trips and by Centurion's crew later led to HMS Bounty being sent on a famous trip to bring the plant to the British West Indies. After avoiding drowning, the next important task was to repair Centurion. The crew moved the cannons and powder barrels to the back of the ship to lift the front out of the water. The carpenters found much to replace and seal. But when the cannons and barrels were put back, water rushed in again. The leak couldn't be found and fixed without proper port facilities.

The main problem with Tinian was that it didn't have a safe place to anchor. So, when a violent storm blew up on the night of September 18, the ship was blown out to sea. This was very upsetting for the small crew of 109 men and boys on board and the 107 men on the island. Although the officer on Centurion had lit flares and fired signal cannons, the storm was so strong that no one on shore even knew what had happened until the next morning. Given the ship's condition and the continuing easterly winds, those on shore thought Centurion had been blown so far west that she might make it to Macau for repairs, or more likely, that she had sunk. In either case, they were now on their own.

There was a small boat on the island, built to carry beef to Guam. It could hold about 30 men, which was clearly not enough. Not wanting to go to Guam where they would be imprisoned, or worse, they decided to make the boat longer and fix it up. They planned to try the 2200-mile voyage to Macau. As work went on, there were worries about fitting everyone, having enough food for a long trip, and not having navigation tools. Many privately preferred to stay on the island, choosing a safe, if lonely, life over the risk of dying at sea. To everyone's surprise, Centurion reappeared after 19 days! Even Anson showed emotion. The crew had fought bravely to keep her afloat, dealing with cannons rolling around, open gun ports letting in water, and only one mast working. Slowly, they regained control, and the ship was able to sail back to Tinian.

A few days later, she was blown off again, this time with most of the men aboard. They were able to get back five days later. Although still not completely seaworthy, on October 20, after taking on fresh water and fruit, Centurion set sail for Macau. She arrived on November 11 after some difficulty finding and getting into port.

The Portuguese had settled Macau in 1557. But over the years, much of the European trade had moved up the Pearl River to Canton. In both places, the Chinese kept firm control, which Anson soon learned. His situation wasn't helped by his refusal to pay port fees. European naval ships usually didn't pay, but the Chinese didn't make that difference. They saw his refusal as an attack on their power. The Portuguese governor of Macau said he couldn't help without orders from the Chinese leader in Canton. When Anson hired a boat to go there, the Chinese first stopped him from boarding. When he arrived, he was told to let local merchants help, but nothing happened after a month.

Among the Chinese merchants, Centurion was seen as a pirate ship. It had destroyed other ships and stopped Pacific trade by keeping the Acapulco galleon in port. This view was probably spread by European rivals. The British East India Company's trade depended on the Chinese authorities. So, they wanted to keep Anson at a distance, at least until their own four ships had left for the season. Back in Macau, Anson wrote directly to the leader, saying his attempts to contact him had failed. He "demanded" all kinds of help. Two days later, a high-ranking official arrived with other officials and carpenters to inspect the ship. When touring the ship, the official was impressed by the heavy cannons and the threat they could cause. Permission to work on the ship was given. It was likely because the Chinese realized it was in their best interest to fix the ship and get rid of her. Soon, the ship was completely unloaded, and a hundred men worked to repair it.

Capturing the Acapulco Galleon

Anson had let it be known that the ship would be leaving for Jakarta and then England. But he had decided that since he had failed so badly to complete his original orders, he would try to save something from the trip. He planned to seize the galleon just before it arrived in the Philippines. It was a huge risk. There were likely to be two galleons this season because his presence off Acapulco had kept the previous one in port.

Shortly after leaving Macau on April 19, 1743, Anson told the crew, who were delighted. Everyone had suffered terribly and lost friends. So, capturing the galleon would bring huge financial rewards. Upon reaching Cape Espiritu Santo, where the galleon usually made landfall, on May 20, the top sails were taken down so the ship wouldn't be seen from land. The ship began sailing back and forth to stay in position and practicing with the guns. There were 227 men aboard, compared to the galleon's normal 400. So, what they lacked in numbers, they would make up for in speed and accuracy. Just as they were losing hope, the galleon was spotted on the morning of June 20. There was only one.

At noon, Centurion moved to block the galleon's escape to land. At one o'clock, she sailed directly in front of the Spanish ship at very close range. This allowed all her big guns to fire at the target while stopping the Spanish from firing back. Meanwhile, skilled shooters in the masts picked off their targets in the opposite masts, the galleon's officers on deck, and those working the guns. The ships drifted further apart, but Centurion could still fire small metal balls (grapeshot) across the galleon's deck and smash cannonballs into her hull.

After ninety minutes, the Spanish surrendered. Anson sent an officer and 10 men over. They found a terrible scene. The decks of the Nuestra Señora de Covadonga were "covered with bodies, guts, and torn limbs." On the Centurion, one man had died, two more would later die from their wounds, and 17 had been injured. The ship had been hit by about 30 shots. On the Covadonga, the grim numbers were 67 dead, 84 wounded, and 150 shots. It was carrying 1,313,843 pieces of eight (which is 33.5 tons of silver) and 1.07 tons of silver. In total, 34.5 tons of silver were captured!

The Spanish had learned about Anson's presence in the Pacific when they stopped at Guam. Although the Portuguese captain had suggested a different, longer route to Manila, the Spanish officers had refused. A merchant in Canton had sent two letters to the governor of the Philippines. The first said how bad Centurion's condition was when she arrived. But the second said the ship had been repaired and suspected Anson might try to capture the galleon. Despite this, only a half-hearted effort was made. A guard ship was sent but ran aground, leaving the galleon unprotected.

The galleon itself was smaller than Centurion but was shockingly unprepared for attack. It had 44 cannons, but 12 of them were packed away. The rest were only small cannons and were mounted on exposed decks. There were also 28 small swivel guns, but since the men on Centurion didn't try to board, these were not a big concern.

Anson needed to leave as soon as possible in case any Spanish ships appeared. He decided to return to Macau. He sent another 40 men to the galleon. By nightfall, the most urgent repairs were done. Three hundred prisoners were moved to Centurion and forced into the hold. Two openings were left for air, but four small cannons were pointed at them to prevent escape. They were limited to one pint of water per day. Although none died on the trip to Macau, which was reached on July 11, conditions below were terrible.

Canton

Anson's return to China was met with disbelief and worry by both the Chinese authorities and the European merchants. On his last visit, Centurion was clearly in trouble. But now, with the damaged Covadonga in tow, it confirmed Chinese fears that he was using their port as a base for piracy or warfare. Europeans worried that their trading rights might be taken away. They also worried that losing the galleon's cargo would ruin trade with Manila.

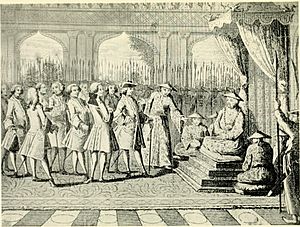

On reaching Macau, Anson sent 60 or 70 prisoners ashore before the Chinese stopped him from unloading the rest. Then he made his way to Canton, intending not to be messed with by the Chinese this time. The Chinese official in charge of the fort came aboard. But he was scared by the ship's heavy guns. Instead, he tried to convince the hired pilots to guide the ship wrongly through shallow waters. When Anson found out, he threatened to hang one of them if the ship ran aground. Once past the forts, the ship waited for permission to go upstream. Anson ordered one of the heavy guns to be fired twice a day. This was to make sure no tricks were tried on them again. After two weeks, the permit arrived, allowing him to get to Whampoa, just before Canton. Most of the prisoners were put onto boats to be taken to Macau. He was able to get fresh supplies, but the merchants would not supply "sea provisions" (food for a long voyage). Anson wanted to speak directly to the Chinese leader. He had asked for a meeting on arrival but was told to wait until after summer. Anson sent a message saying he would arrive on October 1. But as they were about to set off, one messenger said the leader wanted to postpone the meeting. Then another came saying he had waited all day and was offended that Anson hadn't shown up.

Anson then invited himself to stay at the British trading post in Canton. Like those of other nations, it was just outside the city wall by the river. Foreigners were not allowed to enter the city or carry firearms. Officially, they could only talk to certain merchants. At the end of each trading season, they had to leave for Macau or leave China entirely. Although he could collect the supplies he needed, he couldn't get permission to take them onto the ship. Fate stepped in. His crew won praise for fighting a major fire in the city. An invitation to see the leader on November 30 arrived shortly after.

In a very formal meeting, Anson explained through an interpreter that his many attempts to get a meeting through others had failed. He had been forced to send his officer to the city gate with a letter for the leader directly. The leader assured him that the letter was indeed the first time he had known about Anson's arrival. Anson then explained that the right season for returning to Europe had arrived. Provisions were ready, and he just needed the leader's approval. This was immediately given. No mention was made of the unpaid port fees. Anson believed a new rule had been set. But when the next British warship entered Canton in 1764, it paid normal fees.

Returning to England

On December 7, 1743, they sailed from Canton. Stopping at Macau, they sold the captured galleon for a very low price of 6,000 dollars. This allowed the Centurion to leave on the 15th. Anson was eager to reach England before news of the treasure he was carrying reached France or Spain. He didn't want them to try and capture him.

The ship stopped on January 8 at Prince's Island in the Straits of Sunda for fresh water and supplies. It reached Cape Town near the Cape of Good Hope on March 11. He left on April 3 after getting more crew. He arrived home at Spithead on June 15, 1744. He had slipped through fog and avoided a French group of ships that were sailing in the English Channel.

Of those on board, only 188 remained from the original crews of Centurion, Gloucester, Tryal, and Anna. Together with the survivors of Severn, Pearl, and Wager, about 500 had survived out of the original 1900 who sailed in September 1740. Almost all the rest died from disease or starvation.

Anson became a famous person when he returned. He was invited to meet the King. When the treasure was paraded through the streets of London, huge crowds came to see it.

Arguments over the prize money ended up in court. This turned the officers against each other. The main question was the status of the officers from Gloucester and Tryal once they came aboard the Centurion. Anson had not formally promoted them to be officers on his main ship. By the Navy's rules, they lost their rank and were just ordinary sailors. But it seemed clear that without the experienced officers from the other ships, Centurion would not have survived the Pacific or captured the galleon. The difference for one officer was receiving either £500 or £6,000.

Anson received three-eighths of the prize money from the Covadonga. One estimate says this was £91,000, compared to the £719 he earned as captain during the 3-year, 9-month voyage. A regular sailor would have received about £300, which was like 20 years' wages!

Recording the Events

Several private journals of the voyage were published. But the official version came out in London in 1748. It was called A Voyage Round the World in 1740-4 by George Anson Esq, now Lord Anson... Compiled from his Papers and Materials by Richard Walter, MA, Chaplain of His Majesty's Ship The Centurion.... It was a huge popular and commercial success. A fifth edition was already printed by 1749. Besides telling the adventures of the trip, it had a lot of useful information for future sailors. With 42 detailed maps and pictures, it helped lay the groundwork for later scientific trips by Captain Cook and others.

Who Wrote the Book?

The true author of such a successful book has been debated. Some say that the real writer, or at least part of it, was a mathematician named Benjamin Robins. He had written about artillery for the Royal Navy before. Lord Anson's chaplain, Richard Walter, was named as the author on the title page. He had been on the voyage until December 1742. Benjamin Robins is said to have been paid £1,000 for his work. However, the book clearly sounds like it was written by someone who knew "the daily life on board a ship of war." Robins was not such a man. Walter's widow said that her husband worked very closely with Lord Anson on the book every day. She also said that Robins left England before the book was published.

What Happened After

Anson was compared to Francis Drake and was promoted. He became First Lord of the Admiralty in 1751. He also helped the careers of many officers who sailed with him.

Because of the unclear legal situation after the Wager wreck, the rules were changed. Captains were given continued authority over their crew, and the crew kept getting paid. Also, after Anson felt he needed to impress the Chinese officials and show his crew was different from merchant sailors, naval uniforms were introduced. Before, officers and sailors made their own clothing arrangements.

Anson's return sparked interest in the Pacific for British trade and power. But because of the dangerous conditions around Cape Horn and Spain's control of South America, people hoped an easier route to the Pacific could be found through the Northwest Passage over North America. An expedition had been sent while Anson was away, but it was blocked by ice. The government offered £20,000 to anyone who could find a navigable route. But private expeditions also failed.

Anson pushed for more exploration trips after peace was made with Spain. But relations between the countries were still sensitive. The voyages were canceled to avoid causing more disputes. Spanish maps seized from the Covadonga added many islands to British maps of the Pacific. Those in the Western North Pacific became known as the Anson Archipelago.

Given the terrible losses to scurvy, it's hard to understand why there wasn't an official investigation into its cause and possible cures. It was clear that it could be cured. Anson's men quickly got better after reaching Juan Fernandez and Tinian. In one of the world's first controlled experiments, James Lind did his own research in 1747. He worked with twelve scurvy victims. He separated them into six pairs and tried something different on each pair. The pair that received oranges and lemons showed clear improvement. However, the idea of a disease caused by not getting enough nutrients was not yet understood. It would be another 50 years before Lind's findings were put into practice.

The voyage also trained some of the best naval commanders of that time, including Augustus Keppel, John Byron, and John Campbell.

The last known survivor of Anson's voyage was thought to be Joseph Allen, a surgeon on the trip. He died in 1796 at age 83. But a church record from April 1815 mentions the burial of "William Henham, aged 93y. Three days since he was the only man alive that sailed round the world with Lord Anson."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Viaje de Anson alrededor del mundo para niños

In Spanish: Viaje de Anson alrededor del mundo para niños