Diego de Almagro facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Diego de Almagro

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | c.1475 Almagro, Crown of Castile |

| Died | July 8, 1538 (aged 62–63) Cuzco, New Castile, Spanish Empire |

| Nationality | Castilian |

| Spouses | Ana Martínez Mencia |

| Children | Diego de Almagro II (son) Isabel de Almagro (daughter) |

| Parents |

|

| Occupation | Conquistador |

| Known for | Exploration of the Kuna Conquest of Peru Discovery of Chile |

| Military service | |

| Battles/wars | Conquest of Peru

|

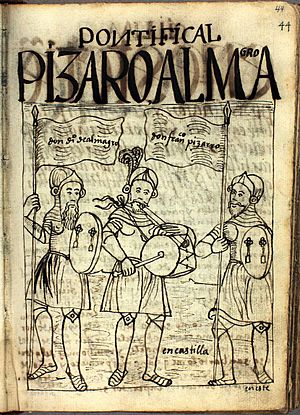

Diego de Almagro (born around 1475 – died July 8, 1538) was a Spanish explorer and soldier, known as a conquistador. He played a big part in the Spanish takeover of South America. He worked with Francisco Pizarro to conquer the Inca Empire in Peru.

Almagro also helped start Spanish cities like Quito in modern-day Ecuador and Trujillo in Peru. Later, he led the first Spanish trip to central Chile. He had a long-running fight with Pizarro over who would control Cuzco, the former Inca capital. This fight led to a civil war between their groups of soldiers. Almagro lost the battle of Las Salinas in 1538 to Pizarro's brothers and was executed a few months later.

Contents

Who Was Diego de Almagro?

His Early Life and Journey to America

Diego de Almagro was born in 1475 in a small village called Almagro in Spain. He was named after the village because his parents, Juan de Montenegro and Elvira Gutiérrez, were not married. To protect his mother's reputation, young Diego was raised by relatives in nearby towns.

When he was four, he returned to Almagro and lived with an uncle. But his uncle was very strict. At age fifteen, Diego ran away from home. He visited his mother, who gave him some bread and coins, telling him to go and that God would help him.

He went to Seville, a big city in Spain. There, he became a servant for an important official named Don Luis Gonzalez de Polanco. One day, Diego got into a fight and hurt another servant. He was going to be put on trial.

Luckily, Don Luis helped him. He arranged for Diego to travel to the New World (America) on a ship. People going to the New World had to bring their own weapons and tools. Don Luis provided these for Diego.

Starting Fresh in the New World

Diego de Almagro arrived in the New World on June 30, 1514. He was in his late thirties. He came with an expedition led by Pedro Arias Dávila to a city called Santa María la Antigua del Darién in Panama. Many other future conquistadors, including Francisco Pizarro, were already there.

We don't know much about what Almagro did right away. But he joined several trips between 1514 and 1515. He later settled in Darien, where he was given land and started farming.

In November 1515, Almagro led his first independent expedition with 260 men. He founded a town called Villa del Acla. But he got sick and had to give command to Gaspar de Espinosa.

Espinosa started a new expedition in December 1515. Almagro and Francisco Pizarro were part of this group. This was the first time Pizarro was named a captain. During this 14-month trip, Almagro, Pizarro, and another man named Hernando de Luque became good friends.

Almagro also became friends with Vasco Núñez de Balboa. Almagro later settled in the new city of Panama. He lived there for four years, managing his own properties and some of Pizarro's. He had a son, El Mozo, with an indigenous woman named Ana Martínez.

Conquering the Inca Empire

By 1524, Almagro, Pizarro, and Luque officially teamed up to conquer lands in South America. They got permission to explore and conquer lands further south. In their first expedition, Almagro lost an eye from an arrow during a battle. After that, he stayed in Panama to find more men and supplies for Pizarro's trips.

Pizarro continued exploring Inca lands. In 1532, he and his men defeated the Inca army led by Emperor Atahualpa at the Battle of Cajamarca. Almagro joined Pizarro soon after, bringing more soldiers and weapons.

After the Spanish took over Peru, Pizarro and Almagro worked together to build new cities. Pizarro sent Almagro to chase after Quizquiz, an Inca general, who was fleeing north to Quito. Another conquistador, Sebastián de Belalcázar, had already reached Quito. He saw that the Inca general Rumiñawi had burned the city and hidden its gold so the Spanish couldn't find it.

Things got more complicated when Pedro de Alvarado arrived from Guatemala, also looking for Inca gold. But Alvarado didn't stay long. Pizarro paid him to leave South America.

Founding New Cities

In August 1534, Almagro founded a city called "Santiago de Quito" near a lake, south of modern-day Quito. He did this to claim the area before Belalcázar. Four months later, he founded the Peruvian city of Trujillo. He named it "Villa Trujillo de Nueva Castilla" to honor Francisco Pizarro's hometown in Spain. These events were some of the last times Pizarro and Almagro were truly friends. Soon after, their friendship broke down over who would control the Inca capital of Cuzco.

A Big Disagreement with Pizarro

After sharing the treasure from the Inca emperor Atahualpa, Pizarro and Almagro went to Cuzco and took the city in 1533. But their friendship started to weaken in 1526. Pizarro had made a deal with King Charles I of Spain, called the "Capitulation de Toledo." This deal gave Pizarro a much bigger share of the conquered lands and rewards, even though they had promised to split everything equally.

Despite this, Almagro still became very wealthy from the conquest of Peru. In November 1532, the King gave him the noble title "Don" and his own coat of arms.

Almagro was living a rich life in Cuzco, but he was very interested in exploring and conquering lands further south. The argument with Pizarro over Cuzco was getting worse. So, Almagro spent a lot of money and time getting 500 men ready for a new trip south of Peru.

In 1534, the Spanish king decided to divide the region into two parts. Francisco Pizarro got "Nueva Castilla" (New Castile), and Diego de Almagro got "Nueva Toledo" (New Toledo), which included southern Peru and present-day Chile. The king had also given Almagro control of Cuzco. This might be why Almagro didn't immediately fight Pizarro for Cuzco. Instead, he decided to go on his new adventure to find riches in Chile.

Exploring New Lands: Chile

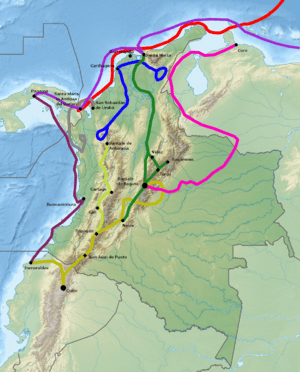

King Charles V had given Diego de Almagro a large area of land south of Francisco Pizarro's territory. On June 12, 1535, Francisco and Diego made a new agreement to share any future discoveries equally. Diego put together an expedition for Chile, hoping to find even more riches than in Peru.

Almagro sent three Spanish soldiers ahead, along with the Inca religious leader Willaq Umu and Paullo Topa, brother of Manco Inca Yupanqui. Juan de Saavedra went ahead with 150 men, and Almagro followed with more forces. On January 23, 1535, Saavedra set up the first Spanish settlement in Bolivia, near the Inca capital of Paria.

The Difficult Journey to Chile

Almagro left Cuzco on July 3, 1535, with his supporters. About 750 Spaniards joined him, hoping to find gold that was missing from Atahualpa's ransom. This ransom had mostly benefited the Pizarro brothers.

Almagro's journey was very hard. He crossed the Bolivian mountains and traveled past Lake Titicaca. Then he set up camp in Tupiza. From there, the expedition went southeast to cross the Andes mountains.

Crossing the Andes was extremely difficult. The cold, hunger, and tiredness caused many Spanish soldiers and native people to die. Slaves, who were not used to such harsh weather, suffered the most.

At this point, Almagro felt like the whole trip was a failure. He sent a small group led by Rodrigo Orgóñez to explore the land further south.

Luckily, these men found the Valley of Copiapó. There, a Spanish soldier named Gonzalo Calvo Barrientos had already made friends with the local natives. In the Copiapó river valley, Almagro officially claimed Chile for King Charles V.

Disappointment in Chile

Almagro quickly started exploring the new territory. He went up the Aconcagua River valley, where the native people welcomed him. However, his interpreter, Felipillo, who had helped Pizarro before, secretly tried to get the natives to attack the Spanish. But the natives didn't understand the danger and didn't attack.

Almagro sent Gómez de Alvarado with 100 horsemen and 100 foot soldiers to explore further. They reached the Ñuble and Itata rivers. There, the Spanish fought the fierce Mapuche indigenous people in the Battle of Reinohuelén. This battle forced the explorers to return north.

Almagro explored the land himself, but the news from Gómez de Alvarado and the very cold winter confirmed his fears: the expedition was a failure. He never found gold or the rich cities the Inca scouts had told him about. He only found native communities who lived by farming. The local tribes fought hard against the Spanish.

Almagro's two-year exploration of these new lands was a complete failure. Even though he first thought about staying and building a city to honor himself, his initial hope had disappeared. He had even brought his son, El Mozo, to Chile, but that optimism was gone.

Some historians believe Almagro might have stayed in Chile if his senior explorers hadn't convinced him to return to Peru. They urged him to go back and finally take control of Cuzco, so his son would have an inheritance. Disappointed with his experience in the south, Almagro planned his return to Peru. He never officially founded a city in what is now Chile.

The Spanish left the valleys of Chile violently. Almagro allowed his soldiers to steal from the natives, leaving their land empty. The Spanish also captured natives and forced them to carry heavy loads as slaves.

The Final Conflict and Return to Peru

After a very difficult journey across the Atacama Desert, Almagro finally reached Cuzco, Peru, in 1537. His troops returned with "torn clothes" from the long walk through the desert. This is why Peruvians sometimes called Chileans "roto" (torn).

When he returned, Almagro was surprised to find that the Inca leader Manco had rebelled. Diego de Almagro sent a message to the Inca, but by then, the Inca people didn't trust any Spaniards.

Hernando Pizarro's men and Almagro's men made a shaky truce. They tried to figure out where the border of their leaders' lands was, to see which part Cuzco was in. But Almagro's troops quickly took the city and captured the Pizarro brothers, Hernando and Gonzalo, on April 8, 1537.

After taking Cuzco, Almagro faced an army sent by Francisco Pizarro to free his brothers. This army, led by Alonso de Alvarado, was defeated at the Battle of Abancay on July 12, 1537. Alvarado and some of his men were captured. Later, Gonzalo Pizarro and De Alvarado escaped from prison.

Francisco Pizarro and Almagro then talked and made a deal. Almagro released Hernando, the third Pizarro brother, in exchange for control of Cuzco. However, Pizarro never planned to give up the city for good. He was just buying time to build a stronger army to defeat Almagro.

During this time, Almagro became ill. Pizarro and his brothers used this chance to attack him and his followers. Almagro's men were defeated at the Battle of Las Salinas in April 1538. Orgóñez, one of Almagro's leaders, was killed in the battle.

Almagro fled to Cuzco, which was still held by his loyal supporters. But he only found temporary safety. Pizarro's forces entered the city easily. Once captured, Almagro was treated badly by Hernando Pizarro. His requests to appeal to the King were ignored.

Almagro was sentenced to death and executed on July 8, 1538. Hernán Ponce de León buried him in the church of Our Lady of Mercy in Cuzco.

Diego de Almagro's Son: El Mozo

Diego de Almagro II (1520–1542), known as El Mozo (The Lad), was the son of Diego de Almagro I. His mother was an indigenous woman from Panama. After Francisco Pizarro was killed by a group of plotters on June 26, 1541, these plotters quickly declared El Mozo the new Governor of Peru.

El Mozo fought a desperate battle called the battle of Chupas on September 16, 1542. He escaped to Cuzco, but was arrested there. He was immediately sentenced to death and executed in the main square of the city.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Diego de Almagro para niños

In Spanish: Diego de Almagro para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |