Spanish conquest of the Muisca facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish conquest of the Muisca |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish colonization of the Americas | |||||||||

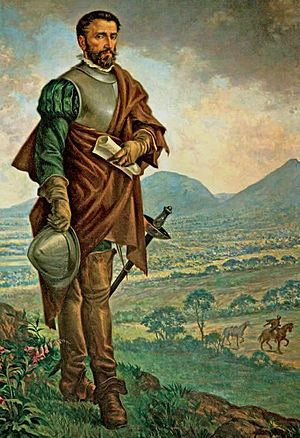

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, the leader of the strenuous conquest expedition from Santa Marta to the Muisca territories |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

of the Spanish Empire |

Guecha warriors of the Muisca |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Gonzalo de Quesada Hernán de Quesada Gonzalo Suárez Rendón Baltasar Maldonado |

Tisquesusa † Sagipa (POW) Eucaneme (POW) Quiminza (POW) Sugamuxi (POW) Saymoso † |

||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| 162 | >30,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||||

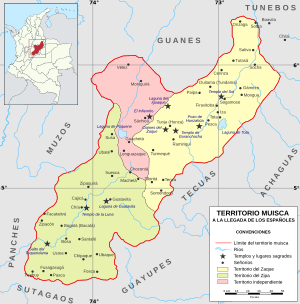

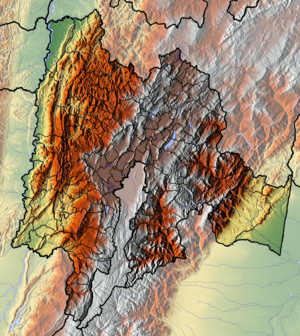

The Spanish conquest of the Muisca happened between 1537 and 1540. The Muisca people lived in the central highlands of Colombia before the Spanish arrived. They were organized into a loose group of different leaders. These included the psihipqua of Muyquytá, the hoa of Hunza, and the iraca of Sugamuxi.

The Muisca were known as the "Salt People" because they mined salt in places like Zipaquirá. They traded valuable items like gold, tumbaga (a gold-copper-silver mix), and emeralds. Their economy was based on farming crops like maize, yuca, and potatoes. Farming started around 3000 BCE in their region.

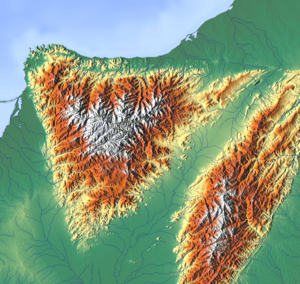

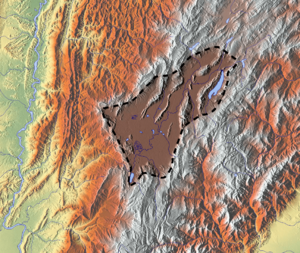

The Muisca lived on the Bogotá savanna, a flat, high plain in the Eastern Andes. This area had very fertile soil. They were a deeply religious society with many gods and advanced knowledge of stars. They used a complex sun-moon calendar. Men and women had different roles. Women handled planting, cooking, salt mining, and making clothes and pottery. Men were responsible for harvesting, fighting, and hunting. Their guecha warriors defended Muisca lands from groups like the Muzo and Panche.

The Muisca created beautiful gold art, even though they didn't have much gold themselves. They got gold through trade. The famous Muisca raft shows a ceremony where a new zipa (leader) covered himself in gold dust and entered Lake Guatavita. This legend of El Dorado (the "Man of Gold" or "City of Gold") made the Spanish very interested.

In 1536, a large Spanish expedition left Santa Marta to find El Dorado. It was led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada. His brother Hernán was second in command. Other Spanish groups also searched for gold from different parts of South America.

The conquest of the Muisca began in March 1537. De Quesada's troops entered Muisca lands in Chipatá. They moved deeper into the highlands, founding towns like Moniquirá and Suesca. In April 1537, they reached Funza, where the zipa Tisquesusa was defeated. This led to more expeditions. By August 1537, the zaque Quemuenchatocha of Hunza was captured. The iraca Sugamuxi of Sogamoso also fell to the Spanish. The Sun Temple was accidentally burned by soldiers.

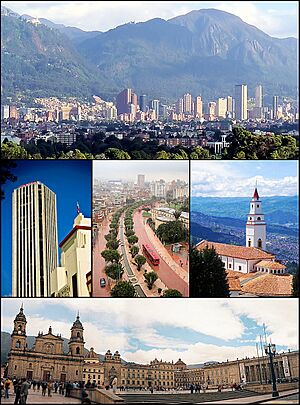

On August 6, 1538, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada founded Bogotá. It became the capital of the New Kingdom of Granada. Later that month, the new zipa, Sagipa, allied with the Spanish to fight the Panche. In the Battle of Tocarema, they won. In 1539, other Spanish leaders arrived. De Quesada and the other leaders returned to Spain. His brother Hernán became governor. New campaigns continued, and the last zaque, Aquiminzaque, was killed in early 1540. This marked the end of the Muisca Confederation.

Contents

Ancient History of the Muisca

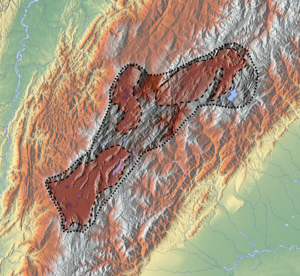

The history of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense before Columbus began around 12,500 years ago. The oldest human evidence was found at El Abra. Early people were hunter-gatherers. Large animals like mammoths also lived there.

Herrera Period

During the Herrera Period (800 BCE to 800 CE), farming grew. People started making pottery. From the 5th century CE, important people were mummified. Many ancient sites on the Altiplano show evidence from this time. One important site in Soacha has remains of 2200 people. It also has pottery, tools, seeds, and small gold offerings called tunjos.

Muisca Confederation

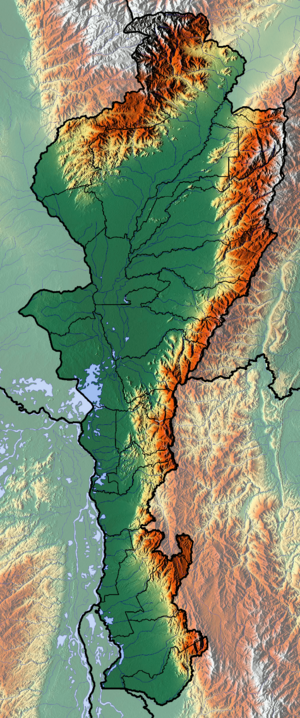

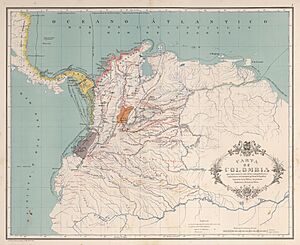

The Muisca Confederation was the name for the lands where the Muisca people lived. It covered about 25,000 square kilometers. Estimates say between 300,000 and 2 million people lived there. The Muisca were mainly farmers. They grew crops on the fertile soils of the valleys.

They were called "The Salt People" because they produced salt from mines. This was a job mainly done by Muisca women. They traded salt and other goods like cotton. The Muisca even made their own golden coins called tejuelo.

Unlike the Aztec or Inca, the Muisca did not build huge stone buildings. Their homes and temples were made of clay, wood, and reeds. They worshipped many gods, especially the Moon (Chía) and the Sun (Sué). They built temples for them, like the Moon Temple in Chía and the Sun Temple in Sogamoso.

Many sacred places were natural, like the lakes on the Altiplano. The most important was Lake Guatavita. Here, the new zipa would cover himself in gold dust and jump into the lake as part of a ceremony. This ritual, shown in the Muisca raft, led to the legend of El Dorado. The Muisca's gold art and their rich salt and emerald mines were the main reasons the Spanish came inland.

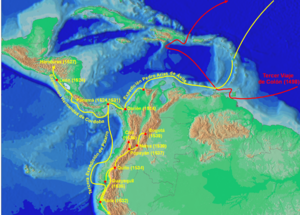

Spanish Exploration and First Cities

The first European to see the mainland of South America was Christopher Columbus in 1498. He explored the coast of Venezuela. Although Colombia is named after him, he never actually set foot in what is now Colombia.

The first European expedition to land on Colombian soil was led by Alonso de Ojeda in 1499. He landed on the La Guajira peninsula. De Ojeda tried to start a colony called Santa Cruz in 1502, but it failed quickly. The local indigenous people fought back fiercely.

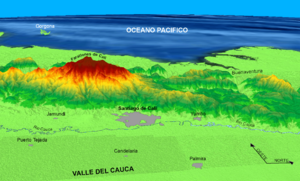

Later, other Spanish cities were founded. Santa Marta was established on July 29, 1525, by Rodrigo de Bastidas. Cartagena was founded on June 1, 1533, by Pedro de Heredia. These cities became important bases for further exploration. In the south, Cali was founded in 1536 by Sebastián de Belalcázar.

Conquest of the Muisca

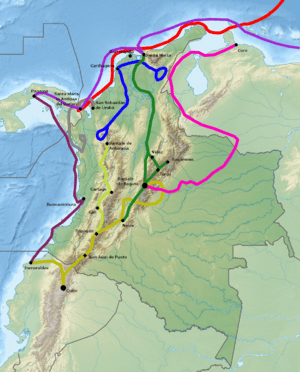

The main expedition into Muisca lands began on April 6, 1536. It was led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada. His brother Hernán was second in command. About 800 soldiers left Santa Marta. Only 173 survived the journey to Muisca territory 11 months later. Other Spanish groups, led by Nikolaus Federmann and Sebastián de Belalcázar, also explored Colombia at the same time.

The Hard Journey to Muisca Land

The first indigenous group the Spanish met were the Tairona. They lived around Santa Marta. In April 1536, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada led two groups. One went by land, and the other went by boat up the Magdalena River. The land journey was extremely difficult. They crossed tough terrain, losing supplies and men. Many boats were shipwrecked, and soldiers were attacked by indigenous groups and crocodiles.

The soldiers faced many dangers in the jungle. These included jaguars, wild boar, snakes, mosquitoes, and poisonous plants. Many became sick or died from snake bites and jaguar attacks. After eight months, they reached La Tora. They rested there for three months. Many more soldiers died from the heat and illnesses.

From Barrancabermeja, they followed the Opón River. They found a canoe with salt and cloth, which was a sign of a great civilization nearby. This motivated them to continue. Gonzalo sent 40 of his weakest men back to Santa Marta. Few of them survived.

In early 1537, the expedition reached Chipatá, the first Muisca settlement. The climate there was much better. Gonzalo stayed for five months to let his men rest. The Muisca of Chipatá gave them new clothes and taught them to drink chicha, a fermented corn drink. The Spanish learned from enslaved indigenous guides that a rich civilization was nearby.

1537 – The Year of Muisca Conquest

Chipatá was the first settlement founded by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada on March 8, 1537. The Spanish troops moved south into the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. They were impressed by the Muisca's organized society and farming. The Muisca were curious but also wary of the Spanish.

The Spanish continued south, passing through towns like Simijaca and Fúquene. They reached Guachetá (founded March 12) and Lenguazaque (founded March 13). On March 14, they founded Suesca. Next, they entered Nemocón, an important salt-producing town. Here, Muisca warriors attacked them for the first time.

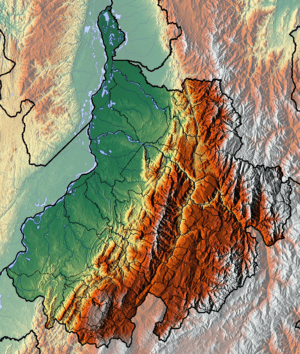

The Spanish defeated the Muisca warriors and continued to Cajicá. From there, they saw the vast, flat plains of the Bogotá savanna, covered with farms. The climate was pleasant. The expedition stopped in Chía for a week. In April 1537, de Quesada led his men to Funza, the zipa's capital. Even though the Spanish army was small (162 men), they defeated the Muisca warriors. Tisquesusa, the zipa, sent messages to other Muisca leaders, but they saw the invaders as sacred and did not attack. Funza was conquered and founded on April 20, 1537.

Conquest of Muyquytá and Hunza

The Muisca leader Tisquesusa learned of the Spanish arrival. He left his capital, Bacatá, and hid. The Spanish found him near Facatativá and attacked him at night. Tisquesusa was wounded by a Spanish soldier and later died from his injuries. His body was found a year later. His sister, Usaca, was hidden but later met a Spanish conquistador, Juan María Cortés. Legend says they fell in love and married. This led to the founding of a colonial village, now part of Bogotá.

In May 1537, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada sent out more expeditions. His captain, Juan de Céspedes, went south and founded Pasca. Gonzalo himself went northeast, searching for El Dorado. He didn't find golden cities, but he found emeralds in places like Chivor. He founded Engativá (May 22) and Chocontá (June 9). He also explored the Tenza Valley, founding Tenza on June 24.

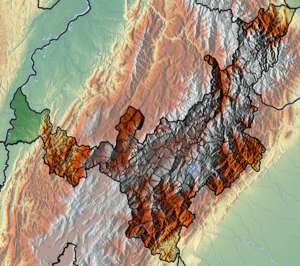

In August 1537, Gonzalo entered the lands of the zaque Quemuenchatocha in Hunza. Quemuenchatocha tried to hide his treasures and avoid the Spanish. But the Spanish, with their better weapons and horses, defeated the Muisca warriors. Gonzalo captured Quemuenchatocha and took him to Suesca. He was pressured to reveal where his treasures were hidden. Quemuenchatocha was later released but died soon after. The Spanish found much gold, emeralds, and silver in Tunja.

After conquering Hunza, Gonzalo de Quesada went to Suamox, the sacred City of the Sun. This city was ruled by the iraca Sugamuxi. The Temple of the Sun was full of gold, emeralds, and mummies. Two Spanish soldiers accidentally set the temple on fire at night. Before it burned, the conquistadors took over 300 kilograms of gold.

Founding of Santafé de Bogotá

By early 1538, the Spanish soldiers were tired. De Quesada divided the treasures they had found. Foot soldiers, horse riders, and captains received different amounts of gold and emeralds. Masses were held for the dead soldiers.

Gonzalo learned that other Spanish groups were approaching. Nikolaus Federmann was coming from the east, and Sebastián de Belalcázar from the south. Gonzalo sent his brother Hernán to meet Belalcázar's group.

On August 6, 1538, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada founded Bogotá. Some historians say it was April 27, 1539, but August 6 is the official date. They built 12 houses and a church. The city was named Santafé de Bogotá. "Santafé" came from a Spanish city, and "Bogotá" from the Muisca capital Bacatá. The new land was called the New Kingdom of Granada.

Later Conquests

Battle of Tocarema

After founding Bogotá, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada went west to fight the Panche. In the Battle of Tocarema on August 20, 1538, the Spanish allied with Sagipa, the new Muisca zipa. De Quesada had 50 soldiers, and Sagipa had between 12,000 and 20,000 Muisca warriors. They defeated the Panche.

However, Sagipa was later arrested by the Spanish. They accused him of ruling illegally and demanded the gold of Tisquesusa. Sagipa refused and hid. When he surrendered, he was pressured to reveal the treasure's location. In early 1539, Sagipa died in the Spanish camp from the harsh treatment.

Return to Spain

The three main leaders, Gonzalo de Quesada, Nikolaus Federmann, and Sebastián de Belalcázar, met in Bosa. They decided to return to Spain to ask the King for rewards. Gonzalo made his brother Hernán the temporary governor of the New Kingdom. Most of Federmann's and Belalcázar's soldiers stayed in Bogotá. In May 1539, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada left for Spain. He would return later to continue searching for El Dorado. He died in Suesca in 1579. Before leaving, the three leaders founded Guataquí on April 6, 1539.

Conquest of Tundama

Tundama, a Muisca ruler in the north, knew about the Spanish conquests. He told his warriors not to surrender. When one warrior suggested surrendering, Tundama cut off his ears and hand. Tundama declared a "death war" against the Spanish. He gathered an army of 10,000 warriors. He also sent a delegation with emeralds and gold to trick the Spanish and gain time to hide his treasures.

On December 15, 1539, Spanish captain Baltasar Maldonado arrived. He offered Tundama peace if he surrendered. Tundama refused, knowing how the Spanish had treated other Muisca leaders. Maldonado attacked Tundama's army. Maldonado had 50 Spanish soldiers and 2,000 indigenous allies. He killed 4,000 of Tundama's warriors. Tundama fled but was later convinced to surrender. Maldonado demanded large amounts of gold and emeralds. When Tundama handed them over, Maldonado felt it wasn't enough and killed Tundama with a hammer.

Early Colonial Period

After founding Bogotá, the Spanish focused on several things. They wanted to extract the rich minerals. They quickly changed farming to include European crops. They also set up a system called encomiendas, where Spanish settlers were given land and indigenous people to work it. A major goal was to convert the Muisca to Christianity.

The Spanish Crown wanted to reduce the Muisca population in certain areas. Indigenous people were forced to live in specific settlements called resguardos. Their traditional religious ceremonies were stopped. The first bishop of Santafé ordered the destruction of Muisca temples. The last public Muisca religious ceremony was in Ubaque in 1563.

Farming changed quickly. By 1555, Muisca people in Toca were growing European crops like wheat and barley. The Muisca's self-sufficient economy changed to one based on intensive farming and mining. This changed their land and culture.

Modern Historical Views

Today, experts study the Muisca and the Spanish accounts. They try to understand the Muisca more accurately. For example, the idea that the Muisca were a very war-like people has been re-examined. Their successful trading was also important. Early Spanish writers, like Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, were all men. This meant their writings might have a biased view.

Many modern female archaeologists and anthropologists, like Ana María Groot, have helped us understand the role of women in Muisca society. They showed that women were very important, especially in salt mining. The idea that the Muisca Confederation was a strict empire has also been questioned.

Some misunderstandings came from language differences. The Spanish used indigenous translators who might not have fully understood the Muisca language. Also, the names of the Muisca rulers, like Tisquesusa and Quemuenchatocha, might have been changed or invented by later Spanish writers. Modern research suggests the Muisca often presented other people to the Spanish to protect their true leaders.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |