Muisca mummification facts for kids

The Muisca people, who lived in the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Colombian Andes long ago, were skilled and developed. They had a special practice called mummification. They mummified important people in their society, like their leaders (called zipas, zaques, and caciques), priests, and their families. These mummies were not buried in the ground. Instead, they were placed in caves or in special houses built just for them.

Many mummies from groups that spoke the Chibcha language, including the Muisca, Lache, and Guane, have been found. In 1602, early Spanish explorers found 150 mummies in a cave near Suesca. They were arranged in a circle, with the leader's mummy in the middle, surrounded by cloths and pots. In 2007, a baby mummy was found in a cave near Gámeza, Boyacá, along with a small bowl, a pacifier, and cotton cloths. Mummification continued even after the Spanish arrived, with some of the youngest mummies dating to the late 1700s.

Early Spanish writers like Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada and Pedro Simón first wrote about Muisca mummies. Later, researchers like Ezequiel Uricoechea and Liborio Zerda in the 1800s, and Eliécer Silva Celis and Abel Fernando Martínez Martín in the 1900s and 2000s, have studied these mummies.

Contents

Who Were the Muisca?

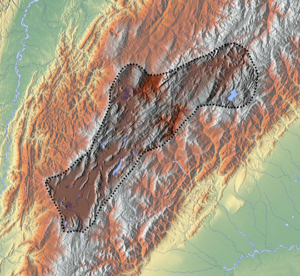

Centuries before the Spanish arrived in 1537, the Muisca people lived on a high plateau called the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. This area is in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes mountains. The Muisca were a developed society, mainly farmers and traders.

Unlike the Maya, Aztec, or Inca, the Muisca did not build large stone structures. Their houses, temples, and shrines were made from wood and clay. They were sometimes called "Salt People" because they mined halite (salt) from places like Zipaquirá, Nemocón, and Tausa.

How Muisca Mummified Their Dead

Mummification was a common practice among many cultures in South America. For example, the Nazca, Paracas, and Chachapoya in Peru also mummified their dead. The oldest known mummies in the Americas are from the Chinchorro culture in Chile, dating back about 7,000 years. Many other cultures in Colombia also practiced mummification, including the Calima, Pijao, and Quimbaya. Closer to the Muisca, the Guane, Lache, Chitarero, and Zenú also mummified their dead.

The Muisca started mummifying people around the 5th century AD.

The Mummification Process

There were two main ways the Muisca prepared bodies for mummification:

- Using a Balm: One method involved taking out the internal organs. Then, a dusty balm, likely a type of resin, was used to dry the body. This process could take about eight hours.

- Using Fire and Smoke: A more common method involved drying the body with fire and smoke. In this process, the organs were not removed. The heat from the fire dried the body, and the smoke helped preserve it, stopping it from decaying. The Guane people also used this method.

What Went with the Mummies?

After being dried, the bodies were wrapped in many layers of cotton cloths, often painted. Emeralds were placed in the mouths and over the eyes and belly button. Sometimes, cotton cloths were even put into other body openings. The ears and nose were also covered with cotton.

During the mummification rituals, the Muisca would sing songs and drink a corn drink called chicha for several days.

The Muisca believed in an afterlife, a world similar to ours. So, mummies were placed with pots of food like beans and maize, more chicha, blankets, and small golden figures. These items were meant to help them in the next world. Mummies of important people were also decorated with golden earrings, noserings, golden feathered crowns, and emeralds.

In 2007, a cave discovery in Gámeza, Boyacá, showed that even children were mummified. A baby mummy, just a few months old, was found wrapped in cotton cloths with a teether, a small bowl, cotton strings, and a small bag around its neck.

Where Mummies Were Placed

Muisca mummies were not buried underground. Instead, they were placed on raised platforms made of reed, like an elevated bed, called barbacoas. Some were placed on small wooden stools. All the mummies found were in a sitting position, with their arms and legs folded towards their body. Some mummies, likely those of warriors, were found holding golden weapons. These warriors were also richly decorated with emeralds, crowns, and fine cotton cloths and bags.

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, who first met the Muisca, wrote that guecha warriors sometimes carried mummies on their backs during battles. This was done to set an example and to scare their enemies. When Spanish soldiers entered the Sun Temple in Sogamoso in 1537, they found mummies decorated with golden crowns and other items sitting on raised platforms.

Different Social Classes

Even though Muisca society was generally fair, the way people were buried showed their social class. Important people and their families were mummified, but common people were not. The places where the mummies of leaders (zipa and zaque) were kept, often in temples and caves, were decorated with golden stools and guarded by priests. Leaders (caciques) were sometimes placed with their slaves and wives. Priests (xeques) were placed in secret spots. Often, the mummies of leaders were kept in their own houses, and religious people would pray to their ancestors there. Sometimes, special houses called bohíos were built as mausoleums just for the mummies of the highest classes.

Mummy SO10-IX: A Special Case

A mummy known as SO10-IX, found near Sativanorte and now in the Archaeology Museum of Sogamoso, has been studied in great detail. It was found by children near the Chicamocha River.

Scientists used carbon dating to find out that this mummy is about 615 years old, meaning it lived between 1300 and 1370 AD.

When researchers first studied Mummy SO10-IX in 2004, they found it was wrapped in a bent position, like a baby in the womb. Parts of its left arm and right leg were missing. Its upper arms were bent, and its hands were tied together with a cotton cord and placed near its head. Cotton blankets were found with it. The mummy also showed signs of insects.

Inside the mummy, researchers found remains of beetles and part of a lung. The skull was normal, and it had straight black hair that looked like it had been cut. Cotton was found inside the ears and nostrils. One of the bones in the spine showed a problem. The mummy was identified as likely a male, about 30 to 35 years old, and about 166 cm (5 feet 5 inches) tall. His teeth had no cavities, and tiny plant and algae remains were found in his mouth.

Based on its pierced ears, researchers believe this mummy might have been a shaman (a spiritual leader). It also showed signs of illnesses in its limbs, suggesting the Muisca community cared for him.

Other Mummies in the Colombian Andes

Muisca mummies have been found in many places, including Gachantivá, Iguaque, Villa de Leyva, Moniquirá, Socotá, Sogamoso, Tunja, Ubaté, Pisba, Usme, and Suesca. Mummies wrapped in cloths were found in Boavita, Tasco, Tópaga, Gámeza, and Gachancipá. In Usme, a large burial site was discovered in 2007, covering about 30 hectares (74 acres). It contained oval and circular graves, pots, and some signs of sacrifices. The 135 human remains found there date from the 8th or 9th century to the 16th century AD.

Mummies from other nearby groups were found in places like Chiscas (Lache), Muzo (Muzo people), Bucaramanga (Guane), and Silos (Chitarero).

By 2012, seventy mummies had been studied in Colombia. Most of them (54) were from Chibcha-speaking groups. The rest were from the Yuko culture. Many mummies found after the Spanish conquest were in caves, arranged in scenes. For example, the 150 mummies found in a cave in Suesca in 1602 were arranged in a circle around the leader's mummy, surrounded by cotton cloths. This circular arrangement was similar to how Muisca villages were set up, with the leader's house in the center.

In 1885, a Muisca scholar named Liborio Zerda described a mummy of a young girl found in a cave high in the mountains near Aquitania. She was wrapped in cotton blankets and decorated with gold items, and her body was in a squatting position.

Some Muisca mummies were so well preserved that their faces still looked like they had just died, even though hundreds of years had passed.

The Zenú and Panche cultures placed their mummies with the head facing east, while the Muzo placed theirs with the head facing west. The Muisca usually placed the heads of their mummies facing east, though some graves have been found facing south.

Where to See Muisca Mummies

Muisca mummies are displayed or kept in museum collections in Colombia and other countries.

- The Museo del Oro in Bogotá has a mummy from Pisba, Boyacá.

- The Museo Arqueológico Casa del Marqués de San Jorge and the Museo Nacional in Bogotá also have Muisca mummies.

- The mummies from Sativasur and Gámeza are kept in the Archaeology Museum in Sogamoso.

- The mummy found in Gachantivá is part of the collection at the British Museum in London.