Muisca architecture facts for kids

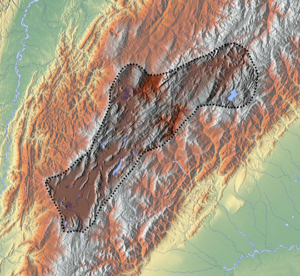

This article explores the architecture of the Muisca people. The Muisca lived in the central highlands of the Colombian Andes, in a region called the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. They were one of the four major civilizations in the Americas before Europeans arrived.

Unlike the Aztecs, Maya, and Incas who built huge stone structures, the Muisca built their homes and temples from materials like wood and clay. These materials don't last as long, so their buildings were more modest. The Muisca were very skilled in farming, gold-working, making cloth, and pottery.

Most of what we know about Muisca buildings comes from archaeological digs. These digs have been happening since the mid-1900s. Sadly, the Spanish conquerors destroyed most of the original Muisca buildings. They replaced them with their own colonial architecture.

However, some Muisca houses (called bohíos) and their most important temple, the Temple of the Sun in Sogamoso, have been rebuilt. These reconstructions help us imagine what Muisca towns looked like.

Contents

Discovering Muisca Architecture

We learn about Muisca architecture from early Spanish explorers and later archaeologists. Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada was the first European to meet the Muisca in 1537. Later, friars like Pedro Simón and Juan de Castellanos wrote about what they saw. Modern archaeologists like Eliécer Silva Celis and Carl Henrik Langebaek have also found important clues.

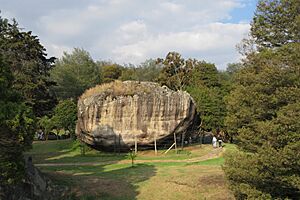

Life Before the Muisca

The high plateau where the Muisca lived has been home to people for at least 12,400 years. The earliest people were hunter-gatherers who lived in caves and rock shelters. You can see evidence of this at places like El Abra and Tequendama.

Around 800 BCE, people started farming more. This led to them moving out of caves and building homes on the plains. The population grew, especially around 800 CE, which is when the Muisca period began. By 1200 CE, Muisca society was more organized, and their communities were larger.

Muisca Homes and Villages

What Muisca Houses Looked Like

The Muisca houses, called bohíos or malokas, were usually round. They were made with wooden poles and clay walls. The roof was shaped like a cone and covered with reeds. A long wooden beam in the middle supported the roof. The inside of the roof was often decorated with colorful cloths. The floors were usually covered with fine straw. Some important houses, perhaps for leaders (caciques), even had ceramic floors.

How Muisca Villages Were Organized

Even though Spanish explorers said the Muisca lands had "great populations," the people lived in small, spread-out villages. This was because their farming methods worked best with smaller settlements. Houses on the Bogotá savanna were often built on slightly higher ground. This helped protect them from floods from the many rivers and swamps in the area.

Each Muisca community had its own farms and hunting areas around their homes. The houses in a village were built around a central square. The house of the cacique (the leader) was usually in the middle. Villages were often surrounded by a fence or enclosure (cercado) with two or more entrances.

Historians like De Quesada described villages with anywhere from 10 to 100 houses. Later in the Muisca period (1200-1537 CE), communities became larger and more crowded, especially in areas like Suba and Cota.

Finding Ancient Homes

Archaeologists have found remains of Muisca houses. For example, in the Las Delicias area of Bogotá, six circular house structures were found. They were about 4.6 meters (15 feet) across. These homes were used from the early Muisca period until the time of the Spanish conquest. Archaeologists found pottery, animal bones, tools, seeds, and jewelry there.

In Soacha, archaeologist Eliécer Silva Celis found evidence of Muisca homes from different time periods. These sites showed signs of fires and animal bones, telling us people lived there for a long time.

Many experts believe that Muisca housing was quite equal. There wasn't a huge difference between the homes of leaders and those of regular people.

Some historical writings mention that the entrance posts of the caciques' houses had special items hanging from them. These items were part of important religious ceremonies, making the houses sacred.

Muisca Roads

The Muisca built unpaved roads. This makes them hard to find today. Some roads were used for trade, connecting the Muisca with their neighbors to the east, north, and west. Other roads were sacred paths used for religious journeys. For example, holy roads were found in Guasca and near the Siecha Lakes.

Roads that crossed the mountains were narrow. This made it tough for the Spanish conquerors, especially with their horses. But once they reached the open plains of the Bogotá savanna, moving around became much easier.

Muisca Temples

The Muisca religion was very important to them, and they built many temples. The most sacred temples were the Temple of the Sun in Sugamuxi and the Temple of the Moon in Chía. The Sun Temple honored Sué, the Sun god, and the Moon Temple honored his wife, Chía. Another famous temple was the Goranchacha Temple, which Muisca myths say was built by a leader named Goranchacha.

Pedro Simón wrote that temples were built with strong wood from the guayacán tree so they would last a long time.

Other Muisca Structures

Besides houses and temples, the Muisca also had other special places, mostly for religious reasons. They held ceremonies at natural sites like Lake Guatavita and Lake Tota. They also built specific spots for rituals, such as the Cojines del Zaque (meaning "Cushions of the Zaque") and the Hunzahúa Well, both in Hunza (modern-day Tunja).

There's a story that the Muisca built a stone fortress in Cajicá, which would be unusual since most of their buildings were wood and clay. This fortress was said to have thick, tall walls. However, modern scientists are not sure if this stone structure really existed before the Spanish arrived.

After the Spanish Conquest

After Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada conquered the Muisca capital, Bacatá (which later became Bogotá), the Spanish quickly started building their own structures. They first built twelve houses and a church in the Muisca style, using wood and clay.

The Spanish had a policy of tearing down existing Muisca buildings. Since Muisca architecture used non-permanent materials, it was easy for the Spanish to replace them with their own colonial-style buildings.

Rebuilding the Past

Today, you can see reconstructed Muisca bohíos and the important Temple of the Sun at the Archaeology Museum in Sogamoso. These reconstructions were done in the 1940s by archaeologist Eliécer Silva Celis.

Archaeological work in the Bogotá area is often difficult. The city is always growing, and new construction can quickly cover ancient sites. For example, one archaeological site was covered by new buildings just months after it was discovered.

|

See also

In Spanish: Arquitectura muisca para niños

In Spanish: Arquitectura muisca para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |