Muisca art facts for kids

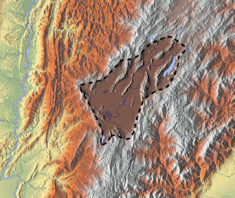

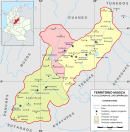

This article is all about the amazing art made by the Muisca people. The Muisca were one of the four big civilizations in the Americas before Christopher Columbus arrived. They lived in the Altiplano Cundiboyacense region, which is now central Colombia.

The Muisca created many types of art, including pottery, woven fabrics, body paint, and rock art. While their buildings were not as grand as those of the Inca, Aztec, or Maya, the Muisca were famous for their incredible gold work. The Museo del Oro in Bogotá, Colombia's capital, has the world's largest collection of gold objects, including many from the Muisca culture.

The first art in the Eastern Andes Mountains of Colombia dates back thousands of years. Even though this was before the Muisca civilization began around 800 AD, some of these early art styles continued to be used.

During ancient times, people in the highlands made rock carvings (petroglyphs) and rock paintings (petrographs). These showed their gods, the many plants and animals of the area, and abstract designs. The Muisca were farmers who grew their own food. Their culture grew, focusing on pottery and getting salt. This period, called the Herrera Period (800 BC to 800 AD), saw the creation of the oldest known Muisca building: El Infiernito ("The Little Hell"), an ancient site for studying the stars.

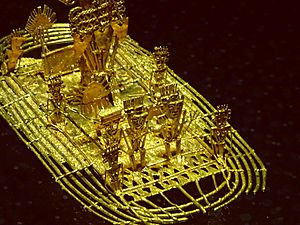

The Herrera Period also saw pottery and textiles become very common. It was also the start of their amazing gold work, which later became a main reason for the Spanish conquest. The best example of Muisca gold art is the Muisca raft. This masterpiece shows the special ceremony where a new leader, the psihipqua of Muyquytá, was chosen. This ceremony happened on a raft in Lake Guatavita. Priests and chiefs wore golden crowns with feathers, and there was music and dance. Stories of these ceremonies led the Spanish to believe in the legend of El Dorado, a mythical golden place.

The rich art of the Muisca still inspires artists and designers today. Muisca designs appear in murals, clothing, and objects. You can even find them in animated videos and video games. Many researchers have studied Muisca art since colonial times. Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, the first Spanish conqueror to meet the Muisca, wrote about their skilled and organized society. Later, people like Alexander von Humboldt and Carl Henrik Langebaek Rueda continued to study and share their knowledge of Muisca art.

Contents

Early Art in the Andes

The central highlands of the Eastern Andes Mountains, known as the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, have been home to people since about 12,500 years ago. This is known from discoveries at places like El Abra near Zipaquirá. The first people were hunter-gatherers who lived in caves and rock shelters. Some of these sites include Tequendama in Soacha and Piedras del Tunjo in Facatativá.

Around 3000 BC, people started living in open areas and built simple round houses. Here, they made stone tools for hunting, fishing, and preparing food. They also created early art, mostly rock art. A key site for this change is Aguazuque, near Bogotá.

Evidence shows that guinea pigs were raised for food at Tequendama and Aguazuque. People also hunted white-tailed deer. Their diet greatly improved when farming began, possibly from people moving north from Peru. The main crop was maize (corn), and tubers (like potatoes) were also important. The rich soil of the Bogotá savanna helped farming grow, which you can still see in the farmlands around Bogotá today.

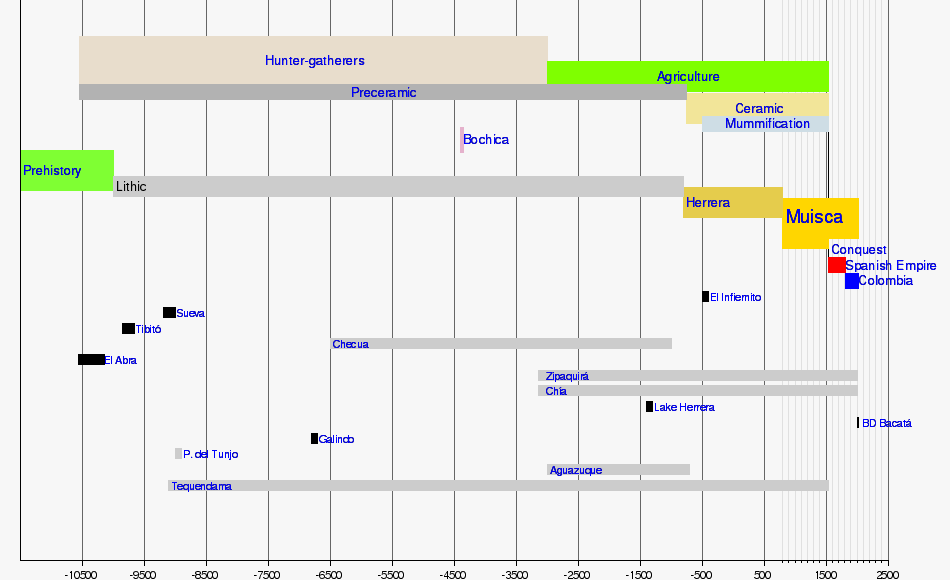

| Timeline of inhabitation of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia | |

|

|

Art Before the Muisca

The first art found in the Altiplano are petrographs (rock paintings) and petroglyphs (rock carvings). These are mostly found in rock shelters on the Bogotá savanna, like El Abra and Tequendama.

The Herrera Period (800 BC to 800 AD) was when the first pottery appeared. The oldest Herrera pottery, from Tocarema, dates back to 800 BC. Herrera art also includes the ancient site El Infiernito, which was used for religious events.

Goldworking in northern South America, especially in Colombia, is thought to have started further south in Peru and Ecuador, between 1600 and 1000 BC. Different goldworking cultures developed in southern Colombia around 500 BC. The first signs of goldworking on the Altiplano appeared late in the Herrera Period. Golden objects found in Tunja and Guatavita are estimated to be from 250 to 400 AD.

Muisca Art Forms

The Muisca period began around 800 AD and lasted until the Spanish conquest of the Muisca in 1537. The Early Muisca Period (800 to 1000 AD) saw more trade with people on the Caribbean coast, the practice of mummification, and the start of goldworking. Later, Muisca society became more complex, with more trade, population growth, and larger settlements near farms. When the Spanish arrived, they saw many Muisca towns on the flat Bogotá savanna.

Animal Figures in Art

Like the Tairona people on Colombia's Caribbean coast, the Muisca made animal figures based on the animals living in their area. Frogs and snakes were very common. Snakes were often made in zig-zag shapes with eyes on top of their heads. Many snake figures also showed their forked tongues and even beards or human heads. Some researchers believe the beards might represent the fish that were an important part of the Muisca diet.

Frogs (called iesua, meaning "food from the Sun" in Muysccubun) were very important to the Muisca. They represented the start of the rainy season. Frog symbols were even used in the Muisca calendar. Frogs appear in many Muisca artworks: painted on pottery, carved in rock art, and as small figures. They were often shown with everyday activities and sometimes represented people, especially women.

Goldworking Skills

The Muisca were famous for their goldworking. Even though they didn't have much gold in their own land, they got a lot through trading. They traded mainly in places like La Tora (now Barrancabermeja) along the Magdalena River. The oldest Muisca gold items found date back to 600-800 AD. These were found in Guatavita and Fusagasugá. Muisca goldwork is similar to, but not exactly the same as, the gold art of the Quimbaya people.

Muisca goldworking developed in stages:

- Early people made gold and copper objects like crowns and offering figures. They used simple molds and hammers.

- Around 400 AD, they became more advanced, using tumbaga (a mix of gold, copper, and silver) and making more offering figures.

- The last stage involved very detailed goldwork, using gold obtained through trade with other groups.

The Muisca traded with groups closer to the Caribbean Coast to get valuable sea snails. These snails were actually worth more than gold to the Muisca, because they lived so far inland in the Andes. The Muisca's amazing gold art led to the El Dorado legend among the Spanish conquerors. This legend drove them on a long, difficult journey into Colombia.

Tunjos: Small Offerings

Tunjos (from the Muisca word tunxo) are small figures used as offerings. The Muisca made many of them. They are often found in lakes and rivers on the Altiplano. Most tunjos look like people, but some look like animals. They were usually made from tumbaga, a mix of gold, copper, and silver, sometimes with traces of lead or iron. Some tunjos made of ceramic or stone have been found in Mongua.

Tunjos had three main uses:

- Decorating temples and shrines.

- Offerings in sacred lakes and rivers as part of religious rituals.

- Placed with the dead to help them in the afterlife.

Ceramic tunjos were kept in Muisca homes, along with emeralds.

Gold and silver were not common in the Muisca lands, but copper was mined in places like Gachantivá. To make these detailed figures, the Muisca used a method called lost-wax casting. They would create a mold, fill it with beeswax (obtained through trade with neighboring groups), and then heat the mold. The wax would melt away, leaving a space for the melted tumbaga or gold to be poured in. This method is still used today to make tunjos in Bogotá.

Spanish writers from the late 1500s reported that the Muisca still used tunjos for religious offerings, even after the Spanish arrived. This shows that their religious practices were still strong, despite efforts to convert them to Catholicism.

The Muisca Raft

The Muisca raft is a true masterpiece of Muisca goldworking. This object, about 19 centimeters long, was found in 1969 in a ceramic pot in a cave near Pasca. It is now the main exhibit at the Museo del Oro in Bogotá.

The raft is believed to show the special ceremony for a new zipa (ruler) at the sacred Lake Guatavita. The new ruler would cover himself in gold dust and jump into the lake to honor the gods. Priests (called xeque) would join this ceremony. This ritual was the basis for the El Dorado legend that attracted the Spanish conquerors to the high Andes. The raft was made using the lost-wax casting method and is mostly tumbaga (about 80% gold, 12% silver, and 8% copper). It weighs 229 grams.

The Muisca raft is also featured on the coats of arms of Sesquilé, where Lake Guatavita is, and Pasca, where the raft was found.

Muisca Jewelry

Muisca society was mostly equal, but there were some differences in who wore jewelry. Guecha warriors, priests, and caciques (chiefs) could wear many types of jewelry. Common people wore fewer pieces. Gold or tumbaga jewelry included diadems (headbands), nose rings, breastplates, earrings, pendants, and bracelets.

Muisca Architecture

Unlike the Maya, Aztec, and Inca, who built huge pyramids and stone cities, the Muisca's buildings were simpler. Their houses (called bohíos or malokas) and temples were made from materials like wood, clay, and reeds, which don't last long. This is why very few traces of their architecture remain today.

The Muisca built circular houses on slightly raised platforms to protect them from floods. Small villages, with 10 to 100 houses, were surrounded by wooden fences called ca. Villages had two or more entrances. Houses and temples were built around a central wooden pole that supported the roof. Temple poles were made from strong Guaiacum officinale trees. House floors were covered with straw, or for chiefs, with ceramic tiles. Cloths painted red and black were hung from the roofs. Tunjos, emeralds, and sometimes remains from special offerings decorated houses and sacred places.

Muisca Roads

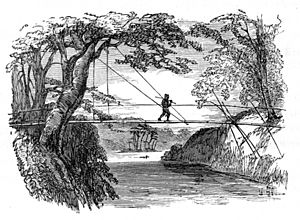

The Muisca used simple dirt roads for trade and travel. These roads are hard to find today. Roads leading to important religious sites, like Lake Tota, were marked with stones, which can still be seen. The Muisca crossed rivers using bridges made of vines and bamboo. Mountain roads were narrow, which was a problem for the Spanish conquerors who used horses.

Remaining Ancient Structures

A few Muisca structures still exist:

- The Cojines del Zaque ("cushions of the zaque") in Tunja are two round stones used for religious ceremonies.

- Of the Goranchacha Temple, only a circle of pillars remains in Tunja.

- The holiest Muisca temple, the Sun Temple in Suamox, was burned by the Spanish. It has been rebuilt based on archaeological research and is now part of the Archaeology Museum in Sogamoso.

-

Muisca bohíos are shown in the upper right of the seal of Sopó.

Muisca Mummies

Mummification was a practice shared by many ancient civilizations. The Muisca continued this tradition, which started in the Herrera Period around 500 AD. They prepared their dead by drying bodies over fires for up to eight hours. This heat preserved the body. After drying, bodies were wrapped in cotton cloths and placed in caves, buried, or sometimes put on platforms inside temples, like the Sun Temple. Mummies were usually placed with their arms folded across their chests and hands near their chins, with legs over the abdomen. During this process, the Muisca played music and sang songs to honor the dead. Mummification continued even after the Spanish arrived, with some mummies found from the late 1700s.

To prepare the dead for the afterlife, mummies were surrounded by ceramic pots with food, tunjos, and cotton bags. Guecha warriors were buried with golden weapons, crowns, emeralds, and cotton. When chiefs like the caciques, zaque, and zipa died, their mummified bodies were placed in special tombs. They were sometimes joined by their wives, servants, and children. A baby mummy found in Gámeza had a teether around its neck. Other child mummies were richly decorated with gold and placed in caves.

When Muisca warriors fought, they sometimes carried the mummies of their ancestors on their backs. This was meant to impress enemies and bring good luck in battle.

Music and Dance

The Muisca played music, sang, and danced mainly during religious ceremonies, funerals, and initiation rituals. They also celebrated with music after harvests, during planting, and after winning battles. Even when building houses, the Muisca performed music and dances. Early Spanish writers noted that the music and singing sounded sad.

Their musical instruments included drums, flutes made of shells or ceramics, golden trumpets, zampoñas (panpipes), and ocarinas. During rituals, people wore feathers and animal skins (especially jaguars) and painted their bodies. Both men and women, and people from all social classes, held hands and danced. The main gods linked to dance were Huitaca and Nencatacoa.

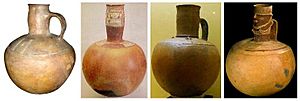

Muisca Ceramics

The Muisca started using ceramics in the Herrera Period, about 3000 years ago. The many different clays from the rivers and lakes in their valleys allowed them to make various types of pottery.

The Muisca made ceramic pots for cooking, for extracting salt from salty water, as decorative ritual pieces, and for drinking chicha (a fermented drink). Large ceramic jars were found around the sacred site of El Infiernito. These were used for big rituals where people drank chicha. Musical instruments like ocarinas were also made of ceramics. Muisca pots and sculptures were often painted with animal figures common in their land, such as frogs, armadillos, snakes, and lizards. Main pottery centers were near places with lots of clay, like Tocancipá and Ráquira.

Muisca Textiles

The Muisca were skilled at making textiles from fique or cotton. They made cords from fique or even human hair. Since cotton didn't grow much in their cold climate, they traded for most of their raw cotton with neighboring groups like the Muzo and Guane. Muisca women then wove this raw cotton into fine mantles (cloaks) that were traded in their many markets.

Muisca mantles were decorated with various colors. They got colors from seeds (like avocado for green), flowers (like saffron for orange and indigo weed for blue), fruits, tree bark, and plant roots. They also used animals, like the cochineal insect for purple, and minerals, like blue and green clays from Siachoque. Colors were applied using pencils, colored threads, or stamps. The Muisca used different weaving techniques, similar to those in South America and Mesoamerica. Small textiles were even used as a form of money, just like small pieces of gold or salt.

In Muisca mythology, the god Bochica is said to have taught the Muisca how to weave and use spindles. The god Nencatacoa protected weavers and painters.

-

The ruana was a special Muisca mantle, similar to a poncho. (This is a modern version.)

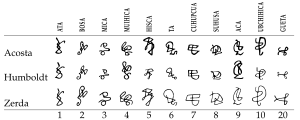

Muisca Numerals and Hieroglyphs

The Muisca did not have a written language for full texts, but they used hieroglyphs (picture symbols) for their numbers. These symbols have been studied by many researchers. They appear in rock art and on textiles. The frog symbol is very important in their number system. It appears five times in the numbers from one (ata) to twenty (gueta). This is because the Muisca did not have separate symbols for numbers 11 to 19. Instead, they combined numbers one to nine with ten. For example, fifteen was "ten-and-five."

Body Art

Tattoos were common for the Muisca and showed who they were. They used the Bixa orellana plant to paint their bodies. Other groups like the Arawak and Tupi also used this plant for body paint.

Muisca Rock Art

Many examples of Muisca rock art have been found in the Altiplano. The first rock art was discovered by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada during the Spanish conquest of the Muisca. This art includes petroglyphs (carvings) and petrographs (drawings). The rock paintings were often made using the index finger. Researchers like Miguel Triana and Eliécer Silva Celis have studied this art in detail.

In the rock art of Soacha-Sibaté, researchers have found specific designs:

- Triangular heads: Human figures with triangular-shaped heads, painted in red.

- Complex hands: Hands drawn with spirals, circles, and more details, found in Sibaté, Saboyá, and Tibaná.

- Radial representations: Main figures with concentric square or circular lines around them. The circular drawings are thought to represent the Muisca gods Chía (the Moon) and Sué (the Sun).

- Rhomboidal motives: Diamond-shaped designs found in Sibaté, whose meaning is still unknown.

- Winged figures: These look like the birds seen in Muisca tunjos and ceramics.

Detailed studies of the rock art in Piedras del Tunjo Archaeological Park in Facatativá show paintings in red, yellow, ochre, blue, black, and white. The designs include what might be a tobacco plant, zig-zag patterns, human figures, concentric lines, animal figures, and human-animal mixes that look like frogs.

Research on the rock art of Sáchica shows plant-like designs, masked human figures, rings, triangular heads, and faces with eyes and noses but no mouths. Most of the rock paintings here are abstract. Red, black, and white are the main colors. Black is thought to be from a time before the Muisca. Radial structures on the heads of human figures are believed to represent feathers. Feathers were very valuable to the Muisca and were worn by priests and chiefs during the El Dorado ritual.

Handprints, similar to those in Argentina's famous Cueva de las Manos, have been found on rocks in Soacha and Motavita.

Muisca Rock Art Locations

As of 2006, over 3,400 rock art sites had been found in Cundinamarca alone, with more than 300 on the Bogotá savanna. More sites have been discovered since then. Sadly, the rock art at Facatativá is heavily damaged. Efforts are being made to protect this unique cultural heritage. Rock paintings in areas like Soacha are also at risk due to mining activities.

| Town | Department | Altitude (m) town center |

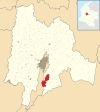

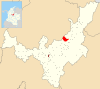

Type | Image | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Abra | Cundinamarca | 2570 | petroglyphs | ||

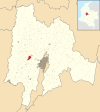

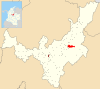

| Facatativá P. del Tunjo |

Cundinamarca | 2611 | petrographs | ||

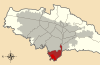

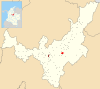

| Tenjo | Cundinamarca | 2587 | petrographs | ||

| Tibacuy | Cundinamarca | 1647 | petrographs | ||

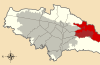

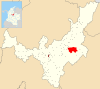

| Berbeo | Boyacá | 1335 | petroglyphs | ||

| Sáchica | Boyacá | 2150 | petrographs | ||

| Bojacá | Cundinamarca | 2598 | petrographs | ||

| La Calera | Cundinamarca | 2718 | petrographs | ||

| Chía | Cundinamarca | 2564 | petrographs | ||

| Chipaque | Cundinamarca | 2400 | petrographs | ||

| Cogua | Cundinamarca | 2600 | petrographs | ||

| Cota | Cundinamarca | 2566 | petrographs | ||

| Cucunubá | Cundinamarca | 2590 | petrographs | ||

| Guachetá | Cundinamarca | 2688 | petrographs | ||

| Guasca | Cundinamarca | 2710 | petrographs | ||

| Guatavita | Cundinamarca | 2680 | petrographs | ||

| Machetá | Cundinamarca | 2094 | petrographs | ||

| Madrid | Cundinamarca | 2554 | petrographs | ||

| Mosquera | Cundinamarca | 2516 | petrographs | ||

| Nemocón Checua |

Cundinamarca | 2585 | petrographs | ||

| San Antonio del Tequendama |

Cundinamarca | 1540 | petrographs | ||

| San Francisco | Cundinamarca | 1520 | petrographs | ||

| Sibaté | Cundinamarca | 2700 | petrographs | ||

| Soacha | Cundinamarca | 2565 | petrographs | ||

| Subachoque | Cundinamarca | 2663 | petrographs | ||

| Suesca | Cundinamarca | 2584 | petrographs | ||

| Sutatausa | Cundinamarca | 2550 | petrographs | ||

| Tausa | Cundinamarca | 2931 | petrographs | ||

| Tena | Cundinamarca | 1384 | petrographs | ||

| Tenjo | Cundinamarca | 2587 | petrographs | ||

| Tequendama | Cundinamarca | 2570 | petrographs | ||

| Tibiritá | Cundinamarca | 1980 | petrographs | ||

| Tocancipá | Cundinamarca | 2605 | petrographs | ||

| Une | Cundinamarca | 2376 | petrographs | ||

| Zipacón | Cundinamarca | 2550 | petrographs | ||

| Zipaquirá | Cundinamarca | 2650 | petrographs | ||

| Bosa | Cundinamarca | 2600 | petrographs | ||

| Usme | Cundinamarca | 2600 | petrographs | ||

| Belén | Boyacá | 2750 | petrographs | ||

| Gámeza | Boyacá | 2750 | petrographs | ||

| Iza | Boyacá | 2560 | petrographs | ||

| Mongua | Boyacá | 2975 | petrographs | ||

| Motavita | Boyacá | 2690 | petrographs | ||

| Ramiriquí | Boyacá | 2325 | petrographs | ||

| Saboyá | Boyacá | 2600 | petrographs | ||

| Tibaná | Boyacá | 2115 | petrographs |

Muisca Art Today

In the center of Bogotá, people still make tunjos using the same methods the Muisca used long ago. While Muisca art isn't as widely known as Maya or Aztec art, modern artists do create new works inspired by it.

In Bosa, a part of Bogotá, a mural shows different Muisca gods and goddesses. Another mural of Muisca deities is in the Hotel Tequendama in Bogotá. Professional graphic designers in Colombia also create modern art based on these gods. The Muisca are even featured in the video game Europa Universalis IV, where you can play as them in an expansion called El Dorado. This game includes many Muisca rulers, from Michuá to Aquiminzaque.

Colombian-Australian artist María Fernanda Cardoso created a piece about the importance of frogs in Muisca culture, called "Dancing Frogs." In the 19th century, writer and future Colombian president Santiago Pérez de Manosalbas wrote a work called Nemequene, about the zipa Nemequene.

-

A statue honoring the messenger god Bochica in Cuítiva, Boyacá.

-

The seal of Guatavita shows a Muisca figure against a shining Sué (Sun god).

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |