Muisca facts for kids

| Muysca | |

|---|---|

Muisca raft (1200–1500 CE)

representation of the initiation of the new zipa at the lake of Guatavita |

|

| Total population | |

| 14,051 (2005, census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Altiplano Cundiboyacense, |

|

| Languages | |

| Chibcha, Colombian Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Muisca religion, Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Guane, Lache, U'wa, Tegua, Guayupe, Sutagao, Panche, Muzo |

The Muisca (also called Chibcha) are an indigenous group and culture from the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in Colombia. They formed a large group called the Muisca Confederation before the Spanish arrived. The Muisca people spoke Muysccubun, a language from the Chibchan family.

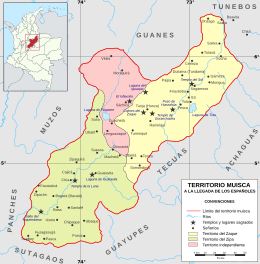

Spanish explorers first met the Muisca in 1537. The Muisca were mainly divided into three groups, each with a powerful leader. The hoa ruled from Hunza, covering parts of modern Boyacá and Santander. The psihipqua ruled from Muyquytá, covering most of modern Cundinamarca. The iraca was a religious leader in Suamox.

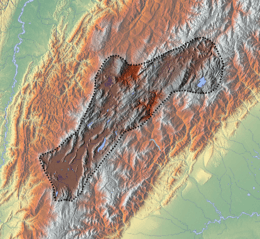

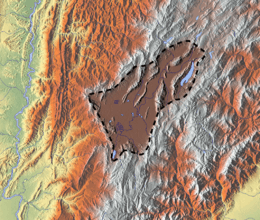

The Muisca territory was about 25,000 square kilometers (9,653 sq mi). It stretched from northern Boyacá to the Sumapaz Páramo. Their land was next to other groups like the Panche and Muzo.

When the Spanish arrived, many Muisca people lived there. Estimates range from 500,000 to over 3 million. Their economy was strong. It was based on farming, salt mining, trading, and making things from metal.

Today, fewer Muisca people remain. Many have blended into the general population. You can find descendants in towns like Cota and Chía. A 2005 census reported 14,051 Muisca people in Colombia.

Many scholars have helped us learn about the Muisca. These include the Spanish explorer Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada and later historians.

Contents

Muisca History

We know about Muisca history up to 1450 mostly from old stories. But writings from the Spanish explorers, called Chronicles of the West Indies, describe the time just before the Spanish arrived.

Early Times

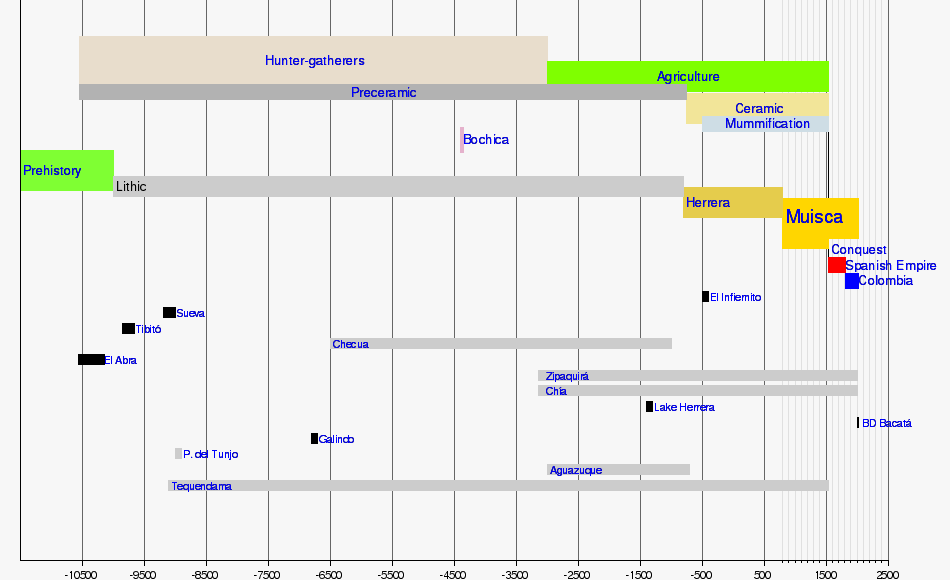

Digs in the Altiplano Cundiboyacense show people lived there since the Archaic age. This was at the start of the Holocene era. Colombia has some of the oldest sites in the Americas. El Abra is about 13,000 years old. Tools found in Tibitó are from 9740 BCE. Human skeletons from 5000 BCE were found at Tequendama Falls. These findings show people from the El Abra Culture lived there.

The Muisca Era

Experts believe the Muisca moved to the Altiplano Cundiboyacense between 1000 BCE and 500 AD. Evidence from Aguazuque and Soacha shows this. Like other early cultures, the Muisca changed from hunting and gathering to farming. Around 1500 BCE, farming groups with pottery skills arrived. They built permanent homes and extracted salt from salty water. The oldest settlement in the highlands is from 1270 BCE.

Between 800 BCE and 500 BCE, more people came. They made colorful pottery and built more homes and farms. These were the groups the Spanish found. The Muisca likely joined with older inhabitants. But the Muisca shaped the culture and how society was organized. Their language, a Chibcha dialect, was similar to languages spoken by groups in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

Conflicts and Warriors

The Zipa Saguamanchica (who ruled from 1470 to 1490) often fought with other tribes. The Sutagao and especially the Panche were frequent enemies. The Caribs also threatened the zaque of Hunza. They often fought over important salt mines. The Muisca had special warriors called güeches.

Timeline of Inhabitation

| Timeline of inhabitation of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia | |

|

|

How the Muisca Were Organized

The Muisca people lived in a confederation. This was a loose group of states that each kept their own power. It was not a kingdom with one absolute ruler. It was also not an empire that controlled other groups. The Muisca Confederation was one of the largest and best-organized groups of tribes in South America.

Each tribe in the confederation had a chief, called a cacique. Most tribes were Muisca, sharing the same language and culture. They traded with each other and united against common enemies. The zipa or zaque was in charge of the army. This army was made up of the brave güeches.

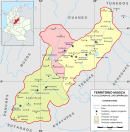

The Muisca Confederation had two main parts. The southern part was led by the zipa, with its capital at Bacatá (now Bogotá). This southern area had most of the Muisca people and was very wealthy.

The northern part was led by the zaque, with its capital in Hunza (now Tunja). Even though both parts shared culture, they sometimes competed. There were four main chiefdoms: Bacatá, Hunza, Duitama, and Sogamoso. These chiefdoms were made of smaller areas. Tribes were divided into Capitanías, led by a Capitan. There were "Great Capitanías" (sybyn) and "Minor Capitanías" (uta). The role of Capitan was passed down through the mother's family.

Here's how their society was structured:

- Confederation (led by zipa or zaque)

-

- --> Priests (Iraca)

- --> Chiefdoms (Cacique)

- --> Capitanía (Capitan)

- --> Sybyn (Great Capitania)

- --> Uta (Minor Capitania)

- --> Sybyn (Great Capitania)

- --> Capitanía (Capitan)

- --> Chiefdoms (Cacique)

- --> Priests (Iraca)

- Lands of the zipa:

- Bacatá rule: Teusaquillo, Tenjo, Subachoque, Facatativá, Tabio, Cota, Chía, Engativá, Usme, Zipaquirá, Nemocón and Zipacón

- Fusagasugá Area: Fusagasugá, Pasca and Tibacuy

- Ubaté Area: Ubaté, Cucunubá, Simijaca, Susa

- Guatavita Area: Gachetá, Guatavita and Suesca, Chocontá, Teusacá, Sesquilé, Guasca, Sopó, Usaquén, Tuna, Suba

- Lands of the zaque:

- Land of Tundama: Cerinza, Oicatá, Onzaga, Sativanorte, Sativasur, Soatá, Paipa, Tobasia

- Land of Sugamuxi: Busbanzá, Toca, Pesca, Pisba, Tópaga

- Independent Chiefdoms: Charalá, Chipatá, Tinjacá, Saboyá, Tacasquirá

The Muisca followed laws based on old customs. These rules were approved by the zipa or zaque. This system worked well for their confederation. Natural resources like forests, lakes, and rivers were shared by everyone.

Muisca Language

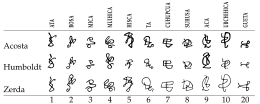

The Muisca language, also called muysca or muysca cubun, belongs to the Chibchan languages family. This language family was spoken in parts of Central America and northern South America. The Tairona and U'wa cultures, related to the Muisca, spoke similar languages. This helped them trade with each other. The Muisca used a type of hieroglyphs for numbers.

Many Muisca words are still used in Colombian Spanish today:

- Places: Many town and region names come from Muisca words. For example, Santa Fe de Bogotá comes from the Muisca word "Bacatá." Many towns in Boyacá and Cundinamarca have Muisca names, like Chocontá and Zipaquirá.

- Fruits: Names for fruits like curuba and uchuva come from Muisca.

- Words for people: The youngest child is sometimes called cuba, or china for a girl. The word muysca itself means "people."

Muisca Economy

The Muisca had a very strong economy and society. This was mainly because their land had valuable resources like gold and emeralds. When the Spanish arrived, they found a rich state. The Muisca Confederation controlled the mining of several important products:

- Emeralds: Colombia is still a top producer of emeralds in the world.

- Copper

- Coal: Coal mines still operate today in places like Zipaquirá. Colombia has large coal reserves.

- Salt: Mines in Nemocón, Zipaquirá, and Tausa produced salt.

- Gold: Gold was brought in from other areas. But it was so plentiful that the Muisca loved to use it for their crafts. The many gold artworks and the tradition of the zipa offering gold to the goddess Guatavita helped create the legend of El Dorado.

The Muisca traded their goods at local markets. They used a system called barter, where they exchanged items instead of using money. They traded everything from daily needs to luxury goods. Salt, emeralds, and coal were so common that they were almost like money.

The Muisca were skilled farmers. They used terrace farming and irrigation in the highlands. Their main crops included fruits, coca, quinoa, yuca, and potatoes.

Another important activity was weaving. The Muisca made many complex textiles. Experts say their weaving skills were very advanced, even compared to today.

Muisca Culture

The Muisca were a farming and pottery-making society in the Andes mountains. Their strong political and administrative system helped them create a unified culture. The Muisca culture has greatly influenced Colombia's national identity.

Symbols and Art

Ancient Muisca patterns appear on the official seals of many modern towns in the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. For example, you can see them in Sopó and Guatavita. The remaining Muisca people in central Colombia also have their own symbol.

Sports and Games

The Muisca had special sports that were part of their traditions. The game of turmequé, also known as tejo, is still popular in Colombia today. Wrestling matches were also important. The winner of a wrestling match received a special cotton blanket from the chief. They were also recognized as a brave guecha warrior.

Muisca Religion

Muisca priests were trained from a young age. They led important religious ceremonies. Only priests were allowed inside the temples. Besides religious duties, priests also advised people on farming or war. The Muisca made special offerings to the Sun god, Sué.

Gods and Goddesses

- Sué' (The Sun god): He was considered the father of the Muisca. His temple was in Suamox, which was a sacred city for the Sun. He was the most worshipped god, especially by the zaques confederation, who believed they were his descendants.

- Chía' (The Moon-goddess): Her temple was in what is now Chía. The zipas confederation worshipped her widely, believing they were her children.

- Bochica: He was a wise leader or hero, not exactly a god, but treated like one. Stories say the land was flooded by Huitaca or Chibchacum. Bochica heard the Muisca's complaints. He used his staff to break two rocks at Tequendama Falls, creating a waterfall that drained the flood. He punished Huitaca by turning her into an owl and making her hold up the sky. Chibchacum was tasked with holding up the Earth.

- Bachué: She was the mother of the Muisca people. Legend says a beautiful woman with a baby came out of Lake Iguaque. Bachué waited for the child to grow up, then they married and had many children, who became the Muisca. Bachué taught them to hunt, farm, follow laws, and worship the gods. She was so loved that the Muisca called her Furachoque (Good woman). When they grew old, Bachué and her husband returned to the lake.

Astronomy and Calendar

The Muisca worshipped two main gods: Sué (the Sun) and Chía (the Moon). They created a calendar based on the number 20. They knew exactly when the summer solstice (June 21) would happen. They called this the Day of Sué, the Sun god. The Sun temple was in Sogamoso, which means "City of the Sun." On the solstice, the zaque went to Sogamoso for a big festival with special offerings. This was the only day the zaque would show his face, as he was seen as a descendant of the Sun god.

Muisca Stories and Myths

The Muisca had many well-known myths and stories. Many Spanish writers who lived in Bogotá recorded these myths. They were interested in the traditions of the people they had conquered. The Muisca territory became the center of Spanish rule in the area.

The Legend of El Dorado

The famous legend of El Dorado ("The Golden One") likely started with the Muisca. The zipa would offer gold and other treasures to the Guatavita goddess. To do this, the zipa would cover himself in gold dust. Then he would wash it off in the lake while throwing gold items into the water. This tradition was known far beyond the Muisca lands. The Spanish were very interested in stories of a "city of gold" that didn't actually exist. Sometimes, indigenous people would send greedy Spaniards in other directions by telling them these stories. Lake Guatavita was explored by explorers looking for the gold offerings. The legend grew, and "El Dorado" became a term for any place where great wealth could be found.

Muisca Homes

The Muisca did not build large stone structures like some other ancient cultures. They used materials like clay, canes, and wood for their homes. Their houses were often cone-shaped. Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, who founded Bogotá, even called the area "Valley of the Palaces" because of these homes. The houses had small doors and windows. The homes of important leaders were different from others. The Muisca used little furniture and often sat on the floor.

The Spanish Conquest

The Spanish took advantage of the rivalries between the zaque and the zipa. This helped them conquer the heart of what is now Colombia. Explorers like Sebastián de Belalcázar, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, and Nicolás de Federman were looking for El Dorado. They discovered the rich plains of Cundinamarca and Boyacá.

The Muisca leaders tried to unite against the Spanish, but it was too late. The Spanish won. They executed the last Muisca rulers, Sagipa and Aquiminzaque, in 1539 and 1540. In 1542, Gonzalo Suárez Rendón finally ended the last Muisca resistance. The Muisca lands were then divided among the Spanish leaders. Later, the Spanish Crown put De Quesada in charge.

Last Muisca Rulers

Under Spanish Rule

After the Spanish Conquest, the Muisca's way of life changed. Their lands became part of a new Spanish colony called the Nuevo Reino de Granada. The Muisca priests and nobles were removed. Only the Capitanías remained. The Spanish gathered much information about the Muisca culture. They created special areas for the Muisca survivors. These people were forced to work the land for the Spanish under a system called encomienda. The colonial era made Bogotá an important city. People from this area later played a big role in fighting for independence.

Independent Colombia

20th Century Changes

After Colombia became independent in 1810, many indigenous lands were dissolved. The land in Tocancipá was dissolved in 1940. The one in Sesquilé was reduced to only 10% of its original size. Tenjo lost 54% of its land after 1934. The land for the Muisca in Cota was re-established in 1916. It was recognized by the 1991 constitution, but then withdrawn in 1998, and finally restored in 2006.

In 1948, the government banned chicha, a corn-based alcoholic drink. This hurt the Muisca's culture and economy. The ban lasted until 1991. Now, the "Festival of the chicha, maize, life, and joy" is celebrated every year in Bogotá.

21st Century Efforts

Since 1989, Muisca people have been working to rebuild their traditional councils. Muisca Councils are active in Suba, Bosa, Cota, Chía, and Sesquilé. In 2002, they held their "First General Congress of the Muisca People." They formed the Cabildo Mayor del Pueblo Muisca, which is part of the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC).

They want to bring back their language and culture. They also work to protect their lands and support Muisca communities in other towns. The Muisca people of Suba have worked to protect wetlands in Bogotá. Suati Magazine, which means "The Song of the Sun," publishes Muisca poetry and stories.

The community in Bosa has made progress in natural medicine. The community in Cota has started growing quinua again. They regularly trade their products at markets.

A report from late 2006 showed:

- 3 Muisca councils: Cota, Chía, and Sesquilé, with 2,318 people.

- In Capital District, 5,186 people are registered as Muisca.

- In Suba and Bosa, 1,573 people are registered.

- This report does not include all Muisca people or those of mixed Muisca heritage.

Images for kids

-

Muisca raft (1200–1500 CE)

representation of the initiation of the new zipa at the lake of Guatavita -

View of the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes

Lake Tota is clearly visible -

Petroglyphs of El Abra (~11,000 BCE)

-

Muisca numerals as depicted by Acosta, Von Humboldt and Zerda

-

Emerald from Muzo

-

Ruins of the astronomical Muisca temple at El Infiernito ("the little hell") near Villa de Leyva

-

Reconstruction of the Sun temple

Archaeology Museum, Sogamoso -

Famous Muisca raft of El Dorado

Gold Museum, Bogotá -

Map of Nuevo Reino de Granada (1625)

See also

In Spanish: Muiscas para niños

In Spanish: Muiscas para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |