History of Bogotá facts for kids

The history of Bogotá tells the story of the area around Bogotá, the capital city of Colombia. Long ago, groups of native people from Central America moved to this region. Among them were the Muisca, who spoke the Chibcha language. They settled in the high plains of what is now Cundinamarca and Boyacá.

When Spanish explorers arrived, they built a major settlement. Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada founded the city in 1538. It became the capital of Spanish provinces and the main city for the Viceroyalty of New Granada. After Colombia gained independence, Bogotá became the capital of Gran Colombia, and later, the capital of the Republic of Colombia.

Contents

Ancient Times: The Muisca People

The first native people to live in the Bogotá area were the Muisca. They spoke the Chibcha language. When the Spanish arrived, there were likely between 110,000 and two million Muisca people.

The Muisca lived in the cool highlands between the Sumapaz mountains and the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy. Their land covered about 25,000 square kilometers (9,650 square miles). This area included the high plains of Bogotá, parts of Boyacá, and a small part of Santander. The best farming lands were old lake beds, like the Bogotá savanna. This area was called Bacatá.

The Muisca had a special way of organizing their land. The northern part was ruled by a leader called the zaque from Tunja. The southern part, Bacatá, was ruled by the zipa. The Muisca were mostly farmers and traders. They lived in many small villages with wooden and clay houses. The iraca from Sogamoso was their main religious leader.

The Muisca grew many crops like maize (corn), potatoes, beans, and tomatoes. They were known as the "Salt People" because they got salt from special water in places like Zipaquirá. They also mined Emeralds in Chivor and traded them with other groups.

Muisca Beliefs and Stories

The Muisca had many interesting myths and religious beliefs. Chía was a special place for worshipping the moon, while Sogamoso was for the sun. They believed their priests watched the stars.

One important story is about Bochica, a god who taught them skills and good behavior. He also saved them from a flood by breaking a rock, which created the Tequendama falls. The Muisca believed lakes were sacred. They offered gold and pottery gifts in lakes like Guatavita. They also honored their dead leaders by mummifying them and burying them with their belongings.

Muisca Art and Craftsmanship

Even though the Muisca didn't have gold themselves, they traded for it with other tribes. They made many beautiful gold objects, especially small figures called tunjos. These figures looked like people or animals and were offered to their gods. They used techniques like lost wax casting and hammering. The Muisca also made gold necklaces, bracelets, and other jewelry. You can see these amazing pieces in the Gold Museum in Bogotá. They also made clothes and pottery.

The Spanish Arrive

In 1533, people believed the Magdalena River led to the Pacific Ocean and the legendary land of El Dorado, a city of gold. Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, a Spanish explorer, wanted to find El Dorado. He left Santa Marta on April 6, 1536, with 800 soldiers.

His group split up, with some traveling by land and others by boat up the Magdalena River. When they met, they heard about native people to the south who made large salt cakes. Quesada decided to change his path and search for these "salt villages" in the Andes mountains. Many soldiers died on the difficult journey, and only 70 men were left when they reached the high plains.

Along the way, they collected a lot of gold and emeralds. They met the Muisca leaders, including the zaque Quemuenchatocha in Tunja. They also raided Sogamoso, where they accidentally burned the Sun Temple.

On March 22, 1537, the Spanish arrived in the Muisca territory, passing through salt-mining villages like Nemocón and Zipaquirá. They found good roads and continued southwest. They passed through several villages, including Cajicá and Chía. They reached Bacatá, the capital of the southern Muisca kingdom, but found it empty. The zipa Tisquesusa had fled and was later killed by a Spanish soldier.

Spanish Rule and the Founding of Bogotá

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada decided to build a city. He chose a spot at the foot of the mountains, near a Muisca village called Teusaquillo. This place had water, wood, good land for farming, and was protected from winds by the mountains of Monserrate and Guadalupe.

The exact date Bogotá was founded isn't clear, but August 7, 1538, is generally accepted. On that day, a priest named Domingo de las Casas held the first church service in a simple hut. The Spanish colony was named New Kingdom of Granada, and its capital was Santa Fe, later called Santa Fe de Bogotá, and then just Bogotá. The name Bogotá comes from the Muisca name Bacatá.

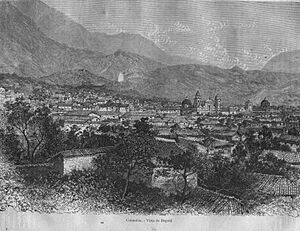

City Layout and Growth

The city was designed with a grid of squares. Streets running east-west were 7 meters (23 feet) wide, and north-south streets were 10 meters (33 feet) wide. In 1553, the main square, now called Bolívar Plaza, was moved to its current spot. The first cathedral was built on its eastern side. The street connecting the main plaza to Herbs Plaza (now Santander Park) was called "Royal Street," which is now Carrera Seventh.

The population of Santa Fe grew quickly, made up of Spanish people, mixed-race people, Muisca, and enslaved people. By 1789, there were over 18,000 residents, and by 1819, about 30,000. The city's importance grew when it became a diocese (a church district).

Government and Education

The city was governed by a mayor and two council members. In 1550, the Audience of Santafé de Bogotá was set up to help manage the area. This made Bogotá the capital of the New Kingdom of Granada. In 1739, it became a Viceroyalty, which it remained until Simón Bolívar led the fight for independence in 1819.

Religious groups played a big role in education. The first universities were founded by Dominican monks in the late 1500s. The San Bartolomé seminar school was founded in 1592 for Spanish children. Later, other important schools like San Francisco Javier (Javeriana University) and Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario were established. In 1783, the first school for girls was founded, giving women the right to education that was previously only for men.

Arts and Science

During the colonial period, art in Bogotá was mostly about religious themes. Famous painters like Gregorio Vázquez de Arce y Ceballos created beautiful works. Wood carving was also very important, with detailed altars in churches.

A major scientific project was the Botanic Expedition, started in 1783. Its goal was to study the native plants of the region. Scientists like José Celestino Mutis and Francisco José de Caldas led this work. They created many detailed drawings of plants. The famous naturalist Alexander von Humboldt also visited Colombia and studied its plants, geography, and people, especially the Muisca.

The Nineteenth Century

The Fight for Independence

People in Spanish colonies across America were restless, and this led to the independence movement in New Granada. One important event was the Revolution of Comuneros in 1781, a riot that Spanish authorities put down. However, leaders like Antonio Nariño continued the fight. He translated and published the "Rights of Men and the Citizen" in Santa Fe.

On July 20, 1810, a small argument over borrowing a flowerpot turned into a big uprising, leading to the cry for independence. The years between 1810 and 1815 are called "Patria Boba" (Silly Homeland). During this time, the new leaders argued among themselves about how to govern, forming the first political parties: federalists and centralists.

In 1815, Spanish forces led by Pablo Morillo arrived to take back control. This period, known as the "Terror Epoch," lasted until 1819. Many important people died, but the war ended with the victory of Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Paula Santander. They won the Battle of Vargas Swamp and the Battle of Boyacá in 1819, securing independence for Colombia.

Gran Colombia and Later Changes

In 1819, Simón Bolívar created Gran Colombia, a large country that included Venezuela, New Granada (Colombia), and Quito (Ecuador). However, this country broke apart in 1830, the same year Bolívar died.

Between 1819 and 1849, not much changed from the colonial period. But in the mid-19th century, major reforms happened. Slavery was abolished, and people gained freedom of religion, education, printing, and trade. The country faced many civil wars, including the "One Thousand Days War" from 1899 to 1902, which was very bloody.

Education and Culture in the 1800s

Bogotá remained the main center for education and culture. In 1823, the Public Library (now the National Library) was expanded, and the National Museum was founded. These institutions were very important for the new republic's cultural growth.

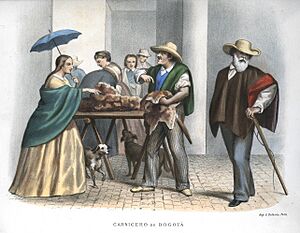

Between 1850 and 1859, the Geographic Commission, led by Italian Agustín Codazzi, studied Colombia's history, geography, and cultures. Artists working with the Commission drew pictures of people, work, clothes, and landscapes across the country.

Many travelers and artists visited Bogotá in the 1800s. They drew and wrote about the nature, people, and daily life they saw. Some stayed and opened art schools. The Mexican artist Santiago Felipe Gutiérrez founded an academy in 1881 that became the National University School of Beaux Arts.

Cultural life in Bogotá revolved around literary gatherings where people shared ideas and enjoyed music and plays. The Cristóbal Colón Theater, opened in 1892, and the Municipal Theatre, opened in 1895, hosted operas and musical shows.

Despite wars, Bogotá kept many traditions from colonial times, mixed with European influences. Chocolate with homemade cookies was a popular treat, and "ajiaco" became a typical dish. People danced the "pasillo," a fast waltz.

New Technologies and City Growth

Bogotá was quite isolated because transportation was difficult. But by the end of the century, things improved with the arrival of the railroad. The first section of the railroad to Girardot was built in 1881. By 1908, the rails connected Bogotá to Facatativá, allowing people to travel to the Magdalena River.

The first telephone line in Bogotá connected the National Palace to the mail and telegraph offices on September 21, 1881. In 1884, public telephone services began.

On December 25, 1884, the first tramway, pulled by mules, started running from Plaza de Bolívar to Chapinero. At first, it ran on wooden rails, but these were replaced with steel rails from England. The tramway served the city until 1948, when buses took over.

The Twentieth Century

The early 20th century was tough for Colombia. The One Thousand Days War (1899-1902) caused great damage, and Colombia lost Panama. But between 1904 and 1909, President Rafael Reyes worked to rebuild the country. Peace led to more economic activity. Bogotá began to change with new buildings and more industry.

In 1910, the Industrial Exposition of the Century showed off the country's progress in industry, crafts, and electricity. Bogotá's economy grew, especially after 1923 when the United States paid Colombia for its role in Panama's separation. This money helped build roads, grow industries, and expand the city's economy.

Political Changes and Urban Growth

In 1930, Enrique Olaya Herrera became president. The Liberal Party, which ruled for 16 years, made many reforms in farming, society, politics, and education. Labor unions became stronger, and more people could go to school.

In 1938, Bogotá celebrated its 400th birthday. The city had grown to 333,312 people. This celebration brought many new buildings and jobs. In 1948, after the killing of liberal leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, downtown Bogotá was largely destroyed, and violence increased. This event, known as the Bogotazo, greatly changed the city.

Life in 20th Century Bogotá

Bogotá's cultural life changed quickly with new communication methods like newspapers, magazines, cinema, and radio. Air travel connected Bogotá to the rest of the world. The city's population exploded as people from rural areas, fleeing violence or seeking work, moved to Bogotá. The population went from 700,000 in 1951 to 2.5 million in 1973.

The city modernized, with more jobs in industry, finance, and construction. During General Rojas Pinilla's rule (1953-1957), television arrived in Colombia. New projects like El Dorado Airport were built, leading to new neighborhoods.

In 1954, several nearby towns like Usme and Suba were added to Bogotá, creating the Special District of Bogotá. This was planned for future growth. In 1991, under a new constitution, Bogotá became the Capital District. By 1993, the population reached almost 6 million.

Economic Development

Bogotá's economy has grown and become very diverse. Industrial production is now very important, with special industrial areas. Craftsmanship is also valued and provides income for many families. Trade, finance, and banking have made Bogotá the economic center of Colombia. The Sabana of Bogotá is now a major flower production area, exporting flowers worldwide and creating many jobs.

Cultural and Educational Growth

Since 1950, there has been a lot of development in architecture, sculpture, painting, music, and literature. Universities now offer many artistic and academic programs. They train professors, researchers, writers, musicians, and filmmakers who are known internationally.

The Twenty-First Century

Bogotá is now a modern city with nearly seven million people, covering about 330 square kilometers (127 square miles). Thanks to new technologies and big changes in recent years, Bogotá offers a rich and varied cultural life. It has modern services as well as traditional neighborhoods.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Bogotá para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Bogotá para niños

- Timeline of Bogotá

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |