El Dorado facts for kids

El Dorado is a famous legend about a lost city of gold. People believed it was hidden somewhere in South America. The story said that the king of this city was so rich he would cover himself in gold dust. He would do this daily or for special events, then wash it off in a sacred lake. Spanish explorers first wrote about this legend in the 1500s. They called the king "El Dorado," meaning 'The Golden One.' Later, the name stuck to the city itself.

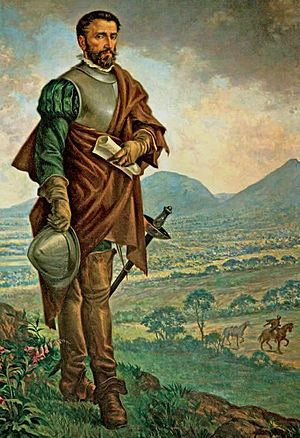

We don't know if this story was completely true. But it might have been inspired by the Muisca people. They were an native group living in the Andean mountains in modern-day Colombia. The Muisca were very skilled at making things from gold. They used gold objects in their religious ceremonies. They also made jewelry and ornaments to trade with other tribes. Early European settlers heard about this gold. They tried many times to reach the Muisca plateau. Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada was the first to succeed in 1537. Quesada and his men took over the Muisca lands for Spain. They took a lot of gold from their palaces and temples.

Soon after, the legend of El Dorado spread among the Europeans. For many years, people searched for the city all over South America. Antonio de Berrio, who inherited Quesada's lands, thought El Dorado was in the Guianas. He tried three times to find a way into the unknown highlands. Before his third try, Walter Raleigh captured him. Raleigh then started his own search in the Guianas.

Raleigh also failed to find the city. But his helper, Lawrence Kemys, learned about a big lake called Lake Parime. People thought this lake was where the golden city might be. Maps in the 1600s showed this lake. But as more areas were explored, people doubted the lake existed. In the early 1800s, Alexander von Humboldt finally said Lake Parime was a myth. This ended the popular belief in El Dorado.

Even though it's a myth, El Dorado has had a lasting impact on culture. The mystery of the lost city and its supposed wealth has inspired many stories. Voltaire included a trip to El Dorado in his 1700s book Candide. More recently, the search for El Dorado has been featured in movies and video games. These include The Road to El Dorado, Paddington in Peru, and Uncharted: Drake's Fortune. It has also inspired music artists like Shakira.

Contents

Why Europeans Looked for Gold

Christopher Columbus was the first European known to reach the Americas in 1492. He landed in the Caribbean islands. When he saw native people wearing gold ornaments, he thought he had found a very rich country. He spent months traveling, looking for the source of the gold. Even though he found no mines, he believed these new lands held great wealth. He promised the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, who funded his trip, that he could "give them as much gold as they have need of."

Columbus knew about old European legends. These stories told of rich, perfect places in the western part of the world. The ancient Greeks believed in the Isles of the Blessed. This was a paradise with perfect weather. Stories said its cities were made of gold, ivory, and emeralds. There was also the mythical continent of Atlantis. It was said to be home to a rich civilization with lots of gold and silver. During the Middle Ages, people told stories of the Isle of Seven Cities. This was a Christian safe haven often shown on maps. It might have inspired the later legend of the Seven Cities of Gold. Columbus also wanted to find places from the Bible, like Ophir and Tarshish. King Solomon was said to have brought huge treasures from these lands. Columbus believed these places, and even the Garden of Eden, were in the newly found continent. Many explorers who came after him shared these beliefs.

However, the first settlers in the Caribbean were disappointed. The native people had some gold, but they didn't mine it in a big way. The Spanish mining efforts quickly used up the local supply. So, the settlers turned their attention to the mainland. They started building colonies along the American coast. At first, things looked unpromising. But then, Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztec Empire and Francisco Pizarro conquered the Inca Empire. These victories brought huge amounts of gold. This made Europeans hope again that vast gold deposits were still waiting to be found.

How the Legend Started

Early Gold Rumors

The first European to enter Venezuela was Ambrosius Dalfinger. He was the governor of the Spanish settlement of Coro. Dalfinger worked for the Welser banking family from Germany. Charles V of Spain had given them control of Venezuela and permission to explore it. The Welsers mainly wanted to find a way through the continent to the Pacific Ocean. This would open a new route to India and help Spain in the spice trade.

In August 1529, Dalfinger started an expedition to Lake Maracaibo. Europeans thought this lake might connect to the Pacific. During their nine-month journey, they took many golden items from the local people. They were told these items came from a tribe high in the mountains. When Dalfinger returned to Coro, he found that people thought he was dead. The Welser family had sent a new governor, Hans Seissenhofer, who named Nikolaus Federmann as his deputy. Dalfinger took back his role but left Federmann in charge while he recovered from an illness.

Federmann quickly used his new power to start his own journey inland. He gave gifts like beads and iron tools to the native tribes. He also looked for information about the Pacific Ocean. He was told that lands near this sea were rich in gold, pearls, and jewels. Federmann's group was led to a hilltop where they saw what looked like a large body of water. This was actually the llanos, a grassy plain that floods often. Federmann failed to find a route to the Pacific. He faced difficult land, many illnesses, and angry natives. So, he had to return to Coro without finding anything.

Dalfinger punished Federmann by banishing him from Venezuela for four years. Dalfinger then went inland again in June 1531. He traveled southwest to the Cesar River. There, he heard about a mountain area called "Xerira." People said this was where all the gold items found among the lowland people came from. This was likely Jerira, at the northern edge of the Muisca plateau. Dalfinger also heard that the tribe making gold objects also sold a lot of salt. With this clue, he led his group south to the trading center of Tamalameque. Then he followed the salt trail into the highlands. At 8,000 feet high, fighting natives in freezing cold, they realized they couldn't go further south. They turned back towards Coro. Dalfinger died on the way back after being shot with a poisoned arrow.

Meanwhile, another group of explorers, led by Diego de Ordaz, searched for the source of the Orinoco River. They sailed inland from the east, rowing hard against the current. They reached where the Orinoco and Meta River meet. They tried to go south along the Orinoco but soon hit rapids they couldn't pass. Going back downriver, Caribs attacked them. Ordaz's men defeated their attackers and captured two. One prisoner was asked about gold nearby. He told the Spaniards that if they followed the Meta River west, they would find a kingdom ruled by "a very brave one-eyed Indian." He said if they found him, "they could fill their boats with that metal." Ordaz tried to follow this advice, but it was the dry season, and the river level was dropping fast. Finally giving up, Ordaz sailed for Spain to plan a second trip. But he died of an illness at sea. Soon, "Meta" became the general name for the legendary golden kingdom.

In 1534, Sebastián de Belalcázar, one of Pizarro's commanders, conquered the Incan city of Quito. He expected to find huge amounts of treasure there. Not finding as much as he hoped, he thought the real treasure was hidden. He started capturing local chiefs to get information from them. One chief captured was not Incan. He said he came from a land twelve days' march to the north. The Spaniards called him el indio dorado, "the golden Indian." It's not clear why, but he might have worn golden armor or other ornaments. Belalcázar was interested in finding this "golden Indian's" homeland. He sent an expedition north, where they found the province of Popayán. However, Belalcázar himself didn't go further at that time.

Conquering the Muisca People

Journeys of Hohermuth and Quesada

After Dalfinger died, Georg Hohermuth von Speyer became the new governor of Coro in 1535. Federmann returned to Coro that same year and became deputy again. Hohermuth sent Federmann on a trip to the Upar valley in the west. Hohermuth led his own trip to the south, hoping to find gold. Hohermuth's group followed the Andes mountains south-southwest along the edge of the llanos. After two years of travel, they reached the Ariari River area. There, they heard rumors of a rich land to the west. But by then, many men had died, and many others were too sick to fight. Hohermuth had to turn back.

On the other side of the mountains, a group led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada was also looking for the land of Meta. This trip started from the Spanish colony of Santa Marta in April 1536. Their goals were to find a land route to Peru and a passage to the Pacific. They thought they could do both by following the Magdalena River to its source. The group traveled south to La Tora (modern-day Barrancabermeja). There, the river became too narrow and fast for them to continue. Even though they had lost many men, Quesada convinced his soldiers not to turn back. He said it "would be ignoble to return with nothing done." He had seen rock salt cakes used by tribes in La Tora. He thought they got the salt from a more advanced society to the east. He remembered the rumors of the "powerful and rich province called Meta." So, like Dalfinger before him, he decided to follow the salt trail into the mountains.

In March 1537, after a long climb, Quesada's group reached a high plateau. They named the place Grita Valley (near modern-day Vélez). This plateau was home to a wealthy civilization. The villages they passed through had lots of gold and emeralds. They were entering the land of the Muisca people.

Quesada's Victory Over the Muisca

The Muisca were farmers who built with wood, not stone. They were not one big tribe. Instead, they were a group of independent chiefdoms. The two most important rulers were the zipa, who ruled the southern lands, and the zacque, who ruled the northern lands. The Muisca were skilled at working with gold and weaving cotton. But they didn't grow much cotton themselves, and they had no gold mines. They got these materials through trade. Their main exports were salt, which they got from natural deposits, and handmade items like gold jewelry and cotton blankets. Most of the gold objects made by the Muisca were actually tumbaga, a mix of gold and copper. Gold was very important in Muisca religion. It decorated their main temples and was used for offerings and burial items. These often looked like human figures called tunjo.

When Quesada arrived at the Muisca plateau, his first move was to march on the zipa's palace at Bacatá (modern-day Funza). The native armies sent to stop the Spaniards were easily defeated. By the end of April, Quesada had entered Bacatá. However, the zipa had escaped, taking all his treasure. After a few failed attempts to find him, Quesada moved to the northern area. He had heard there were emerald mines there. He found the mines at Somondoco, but they were hard to work. His men could only get a few emeralds. So, he continued north to Tunja, home of the zacque. Here, the explorers found "the single greatest haul of treasure in the entire conquest of Muisca territory." They captured the zacque and looted the palace. Then they went to nearby Sogamoso. This was a major religious center and the Muisca's most sacred temple. The Spaniards accidentally burned this temple down. But not before they got another large amount of gold.

Quesada was not satisfied with these gains. He led his men back to Bacatá to continue searching for the zipas treasure. He finally found the ruler's hidden stronghold in the mountains. He launched a night attack, and the zipa was accidentally killed. The zipas successor, Sagipa, made a deal with the Spaniards. But he couldn't tell them where the hidden treasure was and died soon after.

Belalcázar and Federmann Arrive

In early 1539, after almost two years on the plateau, Quesada heard that a group of Europeans were camped in the Magdalena valley near Neiva. This was an army led by Sebastián de Belalcázar. Belalcázar had left Quito quickly in March 1538. He learned that his former general, Francisco Pizarro, had ordered his arrest. Arriving at Popayán, he decided to go east into the highlands. According to Belalcázar's treasurer, Gonzalo de la Peña, the group left Popayán "in search of a land called el dorado." This is the first time this phrase appears in historical records.

Quesada sent a small group to check on the newcomers. The rival groups met peacefully. Soon after, Quesada learned that Belalcázar's forces were coming towards Bacatá. At the same time, his native allies told him that a third army was coming up the slopes from the llanos. This force was led by Nikolaus Federmann.

Federmann had returned to Coro in September 1536 after his trip to the Upar valley. Finding Hohermuth still away, he started an unauthorized journey to the south-southwest, following Hohermuth's path. Survivors of another trip joined him. This trip was led by Jerónimo de Ortal, who had tried to follow Ordaz's path and find the source of the Meta River. His men had rebelled against Ortal and gone off on their own. When they met Federmann, they brought the idea that the legendary land of gold was on higher ground. Federmann, like Hohermuth, traveled along the edge of the Andes. But at one point, he took a detour into the plains. This prevented his group from meeting Hohermuth's returning expedition. Stories from that time suggest Federmann purposely avoided Hohermuth so he wouldn't have to stop his own search and help.

Reaching the Ariari River in late 1538, Federmann heard from the natives that there was much gold to the west. So, he began to climb the Andean slopes. In February 1539, Federmann's tired troops arrived on the plateau near Pasca. Within two months, the armies of Federmann, Quesada, and Belalcázar were camped near each other at Bacatá. Each new arrival believed they had a claim to the plateau and its riches. The geography of South America was still unclear. Belalcázar insisted the Muisca territory was under his control. Federmann argued it was part of Venezuela. Quesada, who was a lawyer, solved the problem by writing a contract. He gave each of his rival explorers a share of the wealth he had taken from the Muisca. All three agreed to return to Spain together and present their claims to the Council of the Indies. Then, on April 29, 1539, the three men together founded the city of Bogotá in the name of Charles V.

How the Legend Grew

Old Stories

Before 1541, there were no written mentions of a place or person called "El Dorado." But in 1541, the historian Oviedo wrote down a story popular among the Spanish in Quito. It was about a native ruler called the "Golden Chief or King":

"They tell me that what they have learned from the Indians is that that great lord or prince goes about continually covered in gold dust as fine as ground salt. He feels that it would be less beautiful to wear any other ornament... He washes away at night what he puts on each morning, so that it is discarded and lost, and he does this every day of the year... The Indians say that this chief or king is a very rich and great ruler. He anoints himself every morning with a certain gum or resin that sticks very well. The powdered gold adheres to that unction... until his entire body is covered from the soles of his feet to his head. He looks as resplendent as a gold object worked by the hand of a great artist."

The timing suggests this story came to Quito from the men who helped conquer the Muisca. Oviedo didn't say where the golden prince was. But by the 1580s, the legend was clearly linked to the Muisca. This is shown in an account by Juan de Castellanos:

"Belalcázar questioned a foreign, traveling Indian living in Quito. He said he was from Bogotá and had come there somehow. He stated that Bogotá was a land rich in emeralds and gold. Among the things that interested them, he told of a certain king, unclothed, who went on rafts on a pool to make offerings. He had seen this, with the king anointing all [his body] with resin and on top of it a quantity of ground gold, from the bottom of his feet to his forehead, gleaming like a ray of the sun... The soldiers, delighted and happy, then gave [that king] the name El Dorado."

A later writer, Antonio Herrera, connected this "traveling Indian" with the indio dorado captured by Belalcázar in 1534. However, modern experts say there's no reason a person from Bacatá would travel so far south to Quito for trade or as a diplomat. It's likely Castellanos's story isn't fully accurate. Belalcázar probably didn't hear the El Dorado legend before he reached Muisca territory.

A new part of Castellanos's story is the king making offerings on a raft. In the early 1600s, Pedro Simón added more details about this ceremony. He claimed it happened at Lake Guatavita near Bogotá. He said the gold dust was offered to a supernatural being living in the lake. Juan Rodríguez Freyle, in 1636, was the first to say the ceremony was an investiture ritual. This means it was a special event for each new zipa (Muisca ruler) to take power. Freyle claimed he got his information from the nephew of the last native ruler of Guatavita.

What We Know Today

Historians disagree on how true these stories are. Warwick Bray says the Spanish conquerors heard the legend from Muisca natives who saw the ceremony. Demetrio Ramos Pérez and John Hemming argue the Spanish invented the story themselves. José Ignacio Avellaneda thinks it's "rather certain" that the legend had some truth. J. P. Quintero-Guzmán suggests the Guatavita ceremony might have been a one-time event. It then lived on in the Muisca's oral history until the Spanish arrived.

Lakes were very important in Muisca religion. People said the mother goddess Bachué came out of a lake before filling the earth with people. Then she returned to the water as a snake. Guatavita was one of several sacred lakes in Muisca territory. It was common for gold, emeralds, and other items to be placed at the lakeside as offerings.

An archaeological discovery called the Muisca raft is often used as proof for the El Dorado legend. It was found in 1969 in a cave near Pasca. This gold object shows a high-ranking man, probably a chief, sitting on a raft surrounded by helpers. Quintero-Guzmán says the link between this object and the golden man legend is "almost undeniable." A similar object was found at Lake Siecha in 1856 but later destroyed in a fire. It was also described as showing the same ceremony. However, others argued it showed a normal boat trip.

The Search for El Dorado Continues

Pizarro and Orellana's Journey

Gonzalo Pizarro, Francisco Pizarro's brother, was governor of Quito when the El Dorado legend grew. In February 1541, he led a trip east from Quito. He hoped to find the country of this golden king. He was guided by a Spaniard who claimed to have been in a place called Cinnamon Valley. This person said that beyond the valley was a flat, open country where people wore gold jewelry. Francisco Orellana, a relative of the Pizarros, was second-in-command.

When they found a few cinnamon trees, Pizarro asked locals about the way to El Dorado. When they couldn't give him information, he had them killed. After some searching, the group reached the Coca River. There, they met a native chief named Delicola. Pizarro's reputation was well known. Delicola quickly told him what he wanted to hear: that further downstream, he would find a rich and powerful civilization. Pizarro built a boat, and the group sailed down the Coca to the Napo River.

On December 25, Pizarro had to stop. His starving men were threatening to rebel. Delicola, who was their prisoner, promised them the land they sought was just a few days down the river. They decided Orellana should take the healthiest men on the boat to find food. Pizarro and the others would follow on foot. However, Orellana couldn't find enough food for Pizarro's army. He soon realized returning upstream would be impossible. He decided to leave Pizarro and sail on. Reaching where the Napo River meets the Amazon, he and his men became the first Europeans to sail the Amazon. They successfully traveled its entire length, eventually reaching the Atlantic Ocean.

During their trip, Orellana's group passed through a long area where the Omagua lived. Orellana was impressed by their religious statues, their well-made pottery, and their good trading routes. He took prisoners and asked them about their culture. They told him that very wealthy people lived a little way inland. But Orellana decided he didn't have enough men to investigate further. Still, his story about the great wealth of the Omagua would influence future trips.

Hernán de Quesada and Philip von Hutten

When Jiménez de Quesada left for Spain, he left his brother Hernán in charge of the Muisca province, now called New Granada. When Hernán de Quesada heard the El Dorado story, he wanted to be the first to find it. He believed his location in Colombia, and his men's local knowledge, would give him an advantage. So, he organized a trip south, leaving Bogotá in September 1541. After some time, suffering greatly from illness and hunger, but pushed on by rumors of golden lands, his group turned west. They found themselves in the region of Pasto, an area already settled by Belalcázar. The trip was considered a failure.

In early 1542, Philipp von Hutten, a German nobleman who had traveled with Hohermuth, set out to find the rich country he was sure Hohermuth had almost found. Bartholomeus Welser, a member of the banking family that governed Venezuela, joined him. Leading their men along the edge of the llanos, they found the tracks of Hernán de Quesada's southbound trip. Thinking Quesada wouldn't have left his province unless he expected to find even greater wealth, they decided to follow the same route. A native chief told them there were no rich settlements in that direction. He added that he heard from neighboring tribes that the Spaniards who passed earlier were all dead or dying. But von Hutten believed this was just an attempt to stop him from his mission.

Towards the end of 1543, on the Guaviare River, von Hutten heard from locals that nearby were "enormous towns of very rich people who possessed countless wealth." He was guided to a village of the Omagua people. He was told the village chief owned several life-sized statues of solid gold. And that even richer chiefs lived beyond. The Europeans attacked. Von Hutten and his captain were badly wounded by native spears. The group retreated to Coro, planning to return with a larger force. However, when they returned, a Spanish rebellion against the Germans led to the execution of Bartholomeus Welser and von Hutten.

Pedro de Ursúa and Aguirre

In 1550, Charles V ordered a halt to all expeditions. A debate was held in Spain about whether they were right. This official pause lasted almost ten years. Then, in 1559, Pedro de Ursúa got permission from the Viceroy of Peru to prepare a trip to the Amazon. By now, many Peruvian settlers believed the fabled El Dorado was in the Omagua lands. Stories from European explorers were confirmed by a group of native Brazilians. They had recently arrived in the Peruvian town of Chachapoyas, having traveled upstream along the Amazon. They said they had been among the Omagua. They spoke of "the priceless value of their riches, and the vastness of their trading." Excited by these reports, Ursúa gathered 370 Spaniards. They set off in small boats on September 26, 1560.

A second goal of the trip was to give jobs to soldiers who were idle after recent civil wars. Among them was Lope de Aguirre, a disgraced former soldier who didn't care about El Dorado and had little loyalty to his leaders. On January 1, 1561, Aguirre led a rebellion against the expedition's leaders. The rebels killed Pedro de Ursúa and chose Fernando de Guzman, a Spanish nobleman, as their new "lord and prince." A few months later, Aguirre had Guzman killed and took command. The search for El Dorado was abandoned. The rebels sailed down the Amazon, planning to conquer Peru. They reached the ocean and sailed north. Then they landed at Borburata and marched overland towards the Andes. At Barquisimeto, the journey ended when Aguirre was killed by his own men.

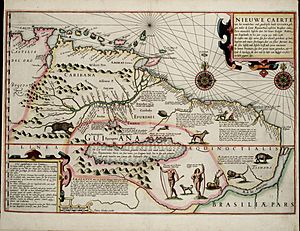

Antonio de Berrio's Search

Quesada died in 1579. His lands and title went to his son-in-law, Antonio de Berrio. Quesada's will said his successor must keep searching "most insistently" for El Dorado. So, Berrio gathered his men and set out across the llanos. By April 1584, he was camped near the Orinoco River, which runs along the western edge of the plain. Berrio believed El Dorado was in the highlands of the Guianas, on the other side of the river. Captured natives confirmed that these highlands had "great settlements and a very great number of people, and great riches of gold and precious stones." They also spoke of a large lake in the Guianas called Manoa. Berrio led his men across the Orinoco. But they soon found they were too tired to continue. He had to turn back home.

In March 1587, Berrio started a second trip. He crossed the river again and spent months exploring the forests on the other side. He searched for a way into the mountains. Eventually, his men rebelled and left him. He had no choice but to return to Bogotá.

During his third attempt, which began in March 1590, Berrio decided to row downstream along the Orinoco, north and east. He wanted to reach the Caroní River, which flows into the Orinoco from the Guianas. The Caroní was known to be hard to navigate. But Berrio hoped he could find a pass to the Guianas by following its banks. When he reached the meeting point, he found he didn't have enough men to climb the mountains. He continued down the Orinoco, reaching the Atlantic Ocean near the island of Trinidad. He and his followers founded a new town on the island, San José de Oruña. They began preparing for a final attack on the Guianas.

Walter Raleigh's Expedition

On March 22, 1595, an English fleet led by Walter Raleigh arrived off the coast of Trinidad. Raleigh was friendly with the Spanish people on the island. He traded with them and invited them onto his ships. After drinking wine, the Spaniards freely talked about Berrio's activities in Guiana, the land's geography, and the riches they believed were inland. On April 7, Raleigh launched a surprise attack on San José and captured Berrio. After getting information from the experienced explorer, Raleigh announced his own plan to go into Guiana and find the golden city.

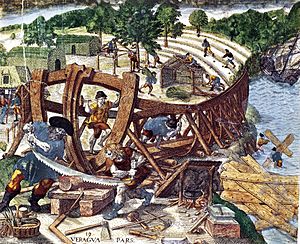

He couldn't bring his large ships into the narrow channels of the Orinoco delta. So, he had his carpenters change one of them (maybe a galleass) so it only needed five feet of water. This ship could carry sixty men, while forty others were in smaller boats. They made slow progress through the delta, soon getting lost in what Raleigh called a "labyrinth of rivers." Eventually, they reached the Caño Manamo, and from there, the main Orinoco River.

A little further upriver, near where the Orinoco and Caroní meet, Raleigh met a native chief named Topiawari. They became friends. Topiawari told him that his people had recently been driven out of inland Guiana by a warlike tribe from the west. This seemed to support the idea, common among the Spanish and strongly believed by Raleigh, that El Dorado was populated by Incans who had escaped from Peru. Topiawari later told Raleigh that the invading tribe was rich in gold. He said their nearest town, just four days' journey south, was the source of "all those plates of gold which were scattered among the borderers, and carried to other nations far and near ... but that those of the land within were far finer."

Raleigh continued to the mouth of the Caroní. Here, the strong current stopped any further progress. He sent out two scouting groups by land, and he went with a third. They found a few precious-looking stones, which the men eagerly dug out with their fingers and daggers. But most of these turned out to be worthless. They heard that at the source of the Caroní, there was a large lake about forty miles wide. People said large amounts of gold could be found there. But with no way to move forward, and threatened by the rising waters of the Orinoco, Raleigh gave up the trip. He hoped to return at a better time.

It wasn't until 1616, over twenty years later, that Raleigh got permission from King James I to try a second trip to Guiana. He promised the king he could find a lot of gold from a certain mine near the Caroní that he had heard about on his first trip. James gave Raleigh strict orders not to fight the Spanish, who still controlled the area around the Orinoco. When he reached South America, Raleigh stayed on his ship. He sent a force led by Lawrence Kemys to find the mine. For unclear reasons, Kemys attacked and captured the Spanish town of Santo Tomé. Raleigh's son Wat was killed in the battle. Unable to find the mine, the men returned to the ship. There, Kemys, facing Raleigh's anger, took his own life. Raleigh was put on trial in England. He was accused of lying about the mine and trying to start a conflict between England and Spain. He was executed.

Lake Parime: The Mythical Lake

During Berrio's first trip, he heard about a huge lake called Manoa. People said it was in the highlands of the Guianas. El Dorado had long been linked to a lake. So, this report made people believe even more that the golden city was somewhere east of the Orinoco. In 1596, Lawrence Kemys heard reports of a lake called Parime or Parima. He thought it was the same as Manoa. People said it was so big that natives "know no difference between it and the main sea." This lake was shown on maps of the Guianas throughout the 1600s, even though no European had ever seen it.

In 1674, two Jesuits, Jean Grillet and François Bechamel, traveled through the area. They found no trace of a lake. In 1740, Nicholas Horstmann discovered Lake Amucu, a little south of where Lake Parime was supposed to be. Amucu was a reedy lake only a mile wide, with no golden city on its banks. People started to doubt Lake Parime's existence. In 1800, Alexander von Humboldt explored the area around the Orinoco. He found that "Parime" was the word local tribes used for any large body of water. He suggested that the seasonal flooding of the plains around Lake Amucu might be the source of the legend. Robert Schomburgk, who visited Lake Amucu in 1836, confirmed this idea. Humboldt's influence eventually led to Lake Parime disappearing from maps and guidebooks. As Schomburgk wrote, it was the "erasing of those last traces of that misleading dream, El Dorado."

El Dorado's Cultural Impact

Even though it's now known as a myth, El Dorado still captures people's imaginations today. One early story to feature the golden city is Candide, a 1759 satire by the French philosopher Voltaire. The book shows the main characters' idealism against the tough realities of life. But in El Dorado, it's different. The city is shown as a "pure Utopia," a perfect place. Yet, the main characters leave because they find its moral perfection boring. Another literary use of the idea is in Edgar Allan Poe's 1849 poem "Eldorado". The story of the "gallant knight" in the poem is usually seen as a metaphor for searching for truth. The last part of the poem hints that it can't be found in this world.

The city has been shown in movies like The Road to El Dorado and Amazon Obhijaan. Some filmmakers have been inspired by the struggles of the explorers. Werner Herzog's Aguirre, the Wrath of God tells a fictional story of Lope de Aguirre's rebellion. The Spanish film Gold, by Agustín Díaz Yanes, shows the challenges of a 1500s Spaniard in America, also partly based on Aguirre. The city was also shown in Dougal Wilson's Paddington in Peru, but not in the usual way. It was a safe place for bears. Video games have also tried to let players experience what early explorers did. A part of the strategy game Age of Empires II lets the player control Francisco de Orellana. Europa Universalis IV: El Dorado lets players send out expeditions to uncover the mysteries of the Americas. The adventure game Uncharted: Drake's Fortune, set in modern times, involves a search for El Dorado. It turns out to be the name of a cursed golden idol.

El Dorado appears in several album and song titles by artists like Neil Young (Eldorado), Electric Light Orchestra (Eldorado) and 24kGoldn (El Dorado). The Colombian artist Shakira supported her El Dorado album with a world tour that ended in Bogotá. Aterciopelados, a Colombian rock group, also have an album called El Dorado. It explores the country's cultural history. El Dorado is also mentioned in the Beatles’ avant-garde song "Revolution 9".

See also

In Spanish: El Dorado para niños

In Spanish: El Dorado para niños

- List of mythological places

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |