Lost-wax casting facts for kids

Lost-wax casting is an ancient way to make copies of sculptures. It's also known as investment casting or cire perdue, which is French for "lost wax." This method is often used to create detailed metal sculptures, like those made from bronze, gold, or silver.

This amazing technique is very old. The first known examples are about 6,500 years old. These were gold items found in Bulgaria. A copper charm from Pakistan is even older, from around 4,000 BC. People in ancient Mesopotamia also used this method. Lost-wax casting was popular in Europe until the 1700s. Today, it's still used for many things, from art to industrial parts.

Contents

How It Works

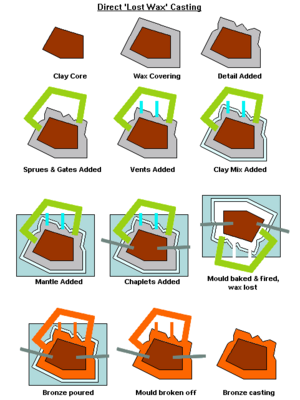

There are two main ways to do lost-wax casting. The "direct method" uses a wax model directly. The "indirect method" makes a wax copy from an original model. Here are the steps for the indirect process:

Making the Model

An artist first creates an original model of the sculpture. This model can be made from clay or wax. Wax and oil-based clay are good choices because they stay soft and easy to work with.

Creating the Mould

Next, a mould is made from the original model. This mould has a soft inner part, usually made of rubber. This inner part is the exact opposite shape of the model. A hard outer mould, often made of plaster, supports the soft inner part. Most moulds are made in pieces so they can be taken apart.

Pouring the Wax

Once the mould is ready, melted wax is poured into it. The wax is swished around to create an even layer inside the mould. This layer is usually about 3 millimeters (1/8 inch) thick. This step is repeated until the wax copy is the right thickness.

Removing the Wax Copy

After the wax cools and hardens, the hollow wax copy is carefully taken out of the mould. The artist can use the same mould to make many wax copies.

Cleaning the Wax

Each wax copy is then "chased." This means a heated metal tool is used to smooth out any marks. These marks might be from where the mould pieces joined. The wax is cleaned up to look like the final sculpture. If parts were moulded separately, they are now heated and attached.

Adding Sprues

A special wax structure, like a tree, is added to the wax copy. These wax "branches" are called sprues. They create paths for the melted metal to flow into the mould later. They also let air escape. A wax "cup" is usually placed at the top of this structure.

Making the Ceramic Shell

The sprued wax copy is dipped into a liquid called silica slurry. Then it's covered with a sand-like material. This creates a hard, ceramic-like shell around the wax. This process is repeated until the shell is thick enough, usually at least half an inch. The bigger the sculpture, the thicker the shell needs to be.

The Burnout

The ceramic-coated piece is placed in a very hot oven, called a kiln. The heat hardens the silica shell. The wax inside melts and runs out, leaving a hollow space. This is why it's called "lost wax." The feeder and vent tubes are also now hollow.

Testing the Shell

After cooling, the ceramic shell is checked for cracks. Water is poured through the feeder and vent tubes to make sure they are clear. Any cracks can be patched up.

Pouring the Metal

The shell is reheated in the kiln to make sure it's completely dry and hot. Then, it's placed in a tub of sand. Metal, like bronze, is melted in a special pot called a crucible. The hot metal is carefully poured into the hot ceramic shell. The shell must be hot, or the temperature difference could break it. The filled shells are then left to cool.

Releasing the Casting

Once cool, the ceramic shell is broken away. This reveals the rough metal casting. The metal sprues are cut off. This extra metal can be melted down and used again.

Finishing the Metal

Finally, the metal casting is "chased" again, just like the wax copy. Any rough spots, like marks from air bubbles or where the sprues were, are filed down and polished. The finished metal piece now looks exactly like the original model.

Jewelry and Small Parts

The lost-wax method is also used to make small items like jewelry. For these, wax models are often made by injecting wax into a rubber mould. These wax pieces are then attached to a wax "tree" structure. This tree is placed inside a metal flask. A special plaster is poured into the flask, covering the wax tree.

After the plaster hardens, the flask is heated in a kiln. The wax melts away, leaving a hollow mould. Hot metal is then poured into this mould. This is often done using special machines that spin the mould or use a vacuum to pull the metal in. This helps the metal fill all the tiny details.

This process can be used with any material that can melt or burn away. Some car makers even use a similar "lost-foam" technique to make engine parts. The model is made of foam, which burns away when hot metal is poured in.

In dentistry, gold crowns and fillings are made using the lost-wax technique. This shows how precise and useful this ancient method still is today.

Glass Sculptures

Lost-wax casting can also create beautiful glass sculptures. First, a sculpture is made from wax. Then, it's covered with a mould material, like plaster, leaving the bottom open. When the mould is hard, it's heated. The wax melts out, destroying the original wax sculpture.

The mould is then placed in a kiln, upside down. Small pieces of glass are put into a funnel-like cup on top. As the kiln heats up, the glass melts and flows into the mould. The glass then cools slowly over several days. Finally, the mould material is removed to reveal the glass sculpture.

History of Lost-Wax Casting

Ancient Discoveries

Some of the oldest gold objects ever found were made using lost-wax casting. These include gold beads and bracelets from Bulgaria's Varna Necropolis, dating back about 6,500 years.

In the Middle East, objects found in Israel from around 3700 BC were also made with this method. In Mesopotamia, people used lost-wax casting for copper and bronze statues from about 3500 BC.

Asia

The oldest copper item made with lost-wax casting is a 6,000-year-old charm from Pakistan. The famous "Dancing Girl" bronze statue from ancient India (around 2300-1750 BCE) was also made this way. This technique was used throughout India for centuries, especially for making beautiful bronze statues during the Chola Period (10th to 12th centuries).

In Southeast Asia, people in places like Thailand and Vietnam used lost-wax casting for items like bangles and drums around 1200 BC. In China, this method became more common around 600 BC. Japan also used it, with a famous example being the large bronze Buddha statue at the Todaiji monastery, made in the 700s.

Africa

In West Africa, skilled artists used lost-wax casting to create amazing bronze sculptures. This started as early as the 800s AD in Nigeria, in places like Igbo-Ukwu and Ife. Later, the Kingdom of Benin became famous for its bronze portraits and reliefs, especially in the 1500s.

Egypt and the Mediterranean

The ancient Egyptians were using lost-wax casting from the mid-2000s BC for jewelry and other items. In the Mediterranean, this technique was very important during the Bronze Age. The ancient Greeks and Romans used it to create large bronze statues. Many of these statues were melted down later, but some have been found in shipwrecks, like the famous Zeus or Poseidon statue.

Americas

People in Central and South America also developed lost-wax casting before Europeans arrived. Cultures in Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia used it to make intricate gold jewelry and bells. This method was used in Mexico starting around the 900s AD.

Literary Mentions

Some old writings mention lost-wax casting. A Roman writer named Pliny the Elder described how to make wax for casting. Another Greek inscription talks about paying artists for their work on a building in Athens around 400 BC.

In India, ancient texts like the Shilpa Shastras (around 320-550 AD) give detailed instructions on casting metal images. The Vishnusamhita even says, "if an image is to be made of metal, it must first be made of wax."

A medieval writer named Theophilus Presbyter, who was a monk and metalworker, wrote a book in the 1100s. It described how to make things like bells and censers using lost-wax casting. He even explained how to mix wax for bells to make them sound right.

Images for kids

-

Hugo Rheinhold's Affe mit Schädel is cast out of bronze using the lost-wax process.

-

The Blätterbrunnen of 1976 by Emil Cimiotti, as seen 2014 in the city center of Hanover, Germany. A lost-wax method was used for the bronze leaves.

See also

- Fusible core injection molding

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |