Rock Springs massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rock Springs massacre |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Nadir of American race relations | |

| Location | Rock Springs, Wyoming, US |

| Date | September 2, 1885 7:00 a.m. – late night (UTC-6) |

|

Attack type

|

Mass murder, massacre, riot |

| Weapons | Various |

| Deaths | At least 28 immigrant Chinese miners (some sources indicate as many as 40 to 50 died) |

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

15 |

| Perpetrators | White miners |

The Rock Springs massacre, also known as the Rock Springs riot, happened on September 2, 1885. It took place in the city of Rock Springs in Sweetwater County, Wyoming. This event was a violent attack by white immigrant miners on immigrant Chinese miners. It was caused by strong feelings against Chinese people, who were seen as taking jobs from white miners. The Union Pacific Coal Department preferred to hire Chinese miners because they would work for less money. This made the white miners very angry.

When the violence ended, at least 28 Chinese miners had died, and 15 were hurt. The attackers also burned 78 Chinese homes. This caused about US$150,000 in damage, which would be a lot more money today.

Tension between white and Chinese immigrants was very high in the American West during the late 1800s. The Rock Springs massacre was one of many violent events that came from years of anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act stopped most Chinese immigration for ten years. But thousands of Chinese immigrants had already come to the American West. Many Chinese immigrants in Wyoming Territory first worked for the railroad. Then, many got jobs in coal mines owned by the Union Pacific Railroad. As more Chinese people arrived, the feelings against them grew stronger among white people. The Knights of Labor, a group against Chinese immigrant workers, started a chapter in Rock Springs in 1883. Most of the attackers were members of this group.

Right after the riot, United States Army soldiers were sent to Rock Springs. They helped the Chinese miners who had survived and fled to Evanston, Wyoming return to Rock Springs a week later. Newspapers reacted quickly. The local newspaper in Rock Springs supported the outcome of the riot. Other Wyoming newspapers mostly felt sorry for the white miners. The massacre in Rock Springs also led to more anti-Chinese violence, especially in the Puget Sound area of Washington Territory.

Contents

Why the Rock Springs Massacre Happened

Chinese people did not immigrate to all parts of the United States equally. Most of the nearly 100,000 Chinese immigrants lived in the American West. This included California, Nevada, Oregon, and the Washington Territory.

The first jobs for Chinese workers in Wyoming were on the railroad. They worked for the Union Pacific company (UP) maintaining the tracks. Chinese workers soon became very helpful to Union Pacific. They worked along UP lines and in UP coal mines from Laramie to Evanston. Most Chinese workers in Wyoming ended up in Sweetwater County. However, many also settled in Carbon and Uinta counties. Most Chinese people in the area were men working in the mines.

Racism against Chinese immigrants was common and not often questioned at the time. People often saw Asian immigrants as "different" in their background, habits, and way of life.

In 1874–75, there were problems with coal production because of worker strikes. So, the Union Pacific Coal Department hired Chinese workers for their coal mines in southern Wyoming. The number of Chinese people grew slowly at first. But where Chinese immigrants lived, they usually lived close together. For example, in a remote camp called Red Desert, 12 out of 20 people were Chinese laborers. They worked under an American boss.

By 1880, most Chinese people in Sweetwater County lived in Rock Springs. While many Chinese workers in Wyoming worked in coal mines, those in Rock Springs also had other jobs. There were Chinese gamblers, a priest, a cook, and a barber. In Green River, Wyoming, there was a Chinese doctor. Chinese servants and waiters worked in Green River and Fort Washakie. Chinese gold miners worked in Atlantic City, Miner's Delight, and Red Canyon, Wyoming. Still, most of the 193 Chinese people in Sweetwater County by 1880 worked in the coal mines or on the railroad.

Reasons for the Attack

The riot happened because of a mix of racism and anger against the Union Pacific company. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. This law stopped Chinese laborers from coming to the United States for ten years. Before the Rock Springs massacre, many people saw the hiring of Chinese workers as unfair.

The white miners in Rock Springs were mostly immigrants from places like Cornwall, Ireland, Sweden, and Wales. They believed that Chinese workers, who were paid less, were lowering their own wages.

The Chinese people in Rock Springs knew about the bad feelings and rising tension with white miners. But they didn't take any special steps to protect themselves. This was because nothing like a race riot had happened there before. The main reasons for the violence were racism and anger about the Union Pacific Coal Department's rules.

Until 1875, only white miners worked in the Rock Springs mines. That year, a strike happened. The company replaced the striking white miners with Chinese workers less than two weeks after the strike began. The company then continued mining with 50 white miners and 150 Chinese miners. As more Chinese workers came to Rock Springs, the anger from white miners grew. At the time of the massacre, there were about 150 white miners and 331 Chinese miners in Rock Springs.

In the two years before the massacre, a "Whitemen's Town" was built in Rock Springs. By 1883, the Knights of Labor started a group there. The Knights were a main group against Chinese workers in the 1880s. In 1882, they had worked to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act. There is no proof that the national Knights of Labor group planned the Rock Springs massacre.

In August 1885, signs were put up from Evanston to Rock Springs. They demanded that Chinese immigrants leave. On the evening of September 1, 1885, the day before the violence, white miners in Rock Springs had a meeting about the Chinese immigrants. It was rumored that threats were made against the Chinese that night.

The Massacre Unfolds

What Happened on September 2, 1885

At 7:00 a.m. on September 2, 1885, ten white men arrived at coal pit number six. They said that the Chinese workers had no right to work in a certain part of the mine. Miners were paid by the ton, so where they worked was important. A fight started, and two Chinese workers were badly beaten. One of them later died from his injuries. The white miners, many of whom were Knights of Labor members, then left the mine.

After this, more white miners gathered near the town. They marched to Rock Springs along the railroad tracks, carrying guns. Around 10:00 a.m., the bell in the Knights of Labor meeting hall rang. The miners inside joined the growing crowd. Some white miners went to saloons instead of joining the mob. But by 2:00 p.m., a Union Pacific official convinced the saloons and grocery stores to close.

With the stores closed, about 150 men, armed with Winchester rifles, moved toward Chinatown in Rock Springs. They split into two groups and entered Chinatown by different bridges. The larger group used the railroad bridge and divided into smaller teams. The smaller group used the town's wooden bridge.

Teams from the larger group went up the hill toward coal pit number three. One team took a spot at the coal shed, another at the pump house. A warning group went into Chinatown first. They told the Chinese people they had one hour to pack and leave town. After only 30 minutes, the first gunshots were fired from the pump house. Then, shots came from the coal shed. A Chinese worker named Lor Sun Kit was shot and fell. As the group from coal pit number three rejoined them, the crowd moved toward Chinatown. Some men fired their weapons as they went. The smaller group of white miners at the wooden bridge also split into teams and surrounded Chinatown. One team stayed at the bridge to stop any Chinese from escaping.

As the white miners moved into Chinatown, the Chinese realized what was happening. They learned that Leo Dye Bah and Yip Ah Marn had already been killed. As news of the murders spread, the Chinese fled in fear. They ran in every direction: up the hill, along the base of other hills, and across Bitter Creek. The mob was coming from three directions.

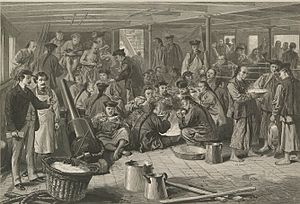

Chinese immigrants who survived the Rock Springs massacre later told the Chinese consul in New York City what happened:

- The mob would stop Chinese people, point a weapon at them, and ask if they had a gun.

- They would search them and steal their watches, gold, or silver before letting them go.

- Some rioters would beat Chinese people before letting them go.

- If they couldn't stop a Chinese person, they would shoot them dead and then rob them.

- Some would throw a Chinese person down, search, and rob them.

- Others would just rob them and tell them to leave quickly.

- Some people just watched, shouted, laughed, and clapped.

By 3:30 p.m., the massacre was in full swing. A group of women in Rock Springs gathered at the wooden bridge, cheering on the violence. Two women reportedly fired shots at the Chinese. As the riot continued into the night, Chinese miners scattered into the hills, hiding in the grass. Between 4:00 p.m. and 9:00 p.m., the rioters set fire to the coal company's camp houses. By 9:00 p.m., almost all Chinese homes were burned. In total, 79 Chinese homes were destroyed. The damage to Chinese property was estimated at about $147,000.

Some Chinese people died on the banks of Bitter Creek as they ran away. Others died near the railroad bridge while trying to escape Chinatown. Some Chinese immigrants who hid in their houses were also killed. One Chinese immigrant was found dead in a laundry house in Whitemen's Town, his home destroyed.

The attacks in Rock Springs were extremely violent. They showed a deep hatred for the victims. There were 28 confirmed deaths, and at least 15 miners were wounded. However, some sources say that 40 to 50 people might have died, as some who fled were never found.

What Happened After the Massacre

Immediate Aftermath

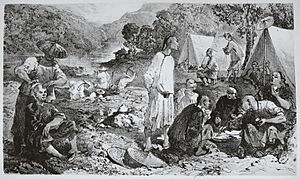

In the days after the riot, Chinese immigrants who survived fled Rock Springs. Union Pacific trains picked them up. By September 5, almost all survivors were in Evanston, Wyoming, about 100 kilometers (60 miles) west of Rock Springs. Once there, they faced threats of violence. Evanston was another area in Wyoming where anti-Chinese feelings were strong.

Rumors quickly spread that the Chinese would return to Rock Springs. On September 3, the Rock Springs Independent newspaper said that if the Chinese returned, "Rock Springs is killed, as far as white men are concerned." The local newspaper defended the massacre. Other western newspapers also supported the white miners' reasons for the riot. However, Wyoming newspapers generally did not approve of the violence itself.

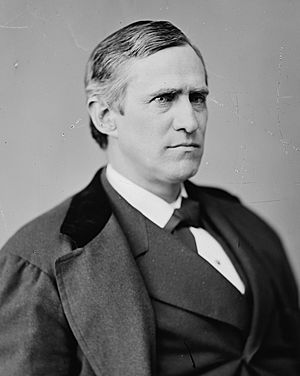

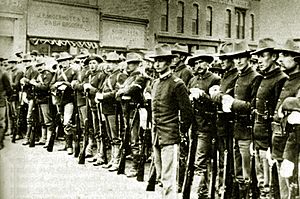

Wyoming's Governor, Francis E. Warren, visited Rock Springs on September 3, 1885, the day after the riot. He wanted to see the situation for himself. After his trip, Warren went to Evanston. From there, he sent messages to U.S. President Grover Cleveland, asking for federal troops. Back in Rock Springs, the riot had calmed down, but the situation was still tense. Two companies of the United States Army's 7th Infantry arrived on September 5, 1885. One company stayed in Evanston, and the other in Rock Springs. More soldiers were ordered to Wyoming.

On September 9, 1885, one week after the massacre, six companies of soldiers arrived in Wyoming. Four of these companies then helped the Chinese people return to Rock Springs. Once back, the Chinese workers found only burned land where their homes used to be. The mining company had buried only a few of the dead.

The situation in Rock Springs became stable by September 15. Governor Warren then asked for the federal troops to be removed. But the mines in Rock Springs stayed closed for a while. On September 30, 1885, white miners, mostly Finnish immigrants and Knights of Labor members, went on strike in Carbon County, Wyoming. They were protesting the company's continued use of Chinese miners. In Rock Springs, white miners were still not back at work in late September because the company still used Chinese labor. Rock Springs became quieter. On October 5, 1885, most of the emergency troops were removed. However, temporary army posts remained in Evanston and Rock Springs for a long time.

The strike by white miners was not successful. They went back to work within a couple of months. The national Knights of Labor group refused to support the strike in Carbon and the holdout by white miners in Rock Springs. They did not want to seem like they approved of the violence at Rock Springs. When the Union Pacific Coal Department reopened the mines, it fired 45 white miners who were involved in the violence.

Arrests and Justice

After the riot, sixteen men were arrested. This included Isaiah Washington, who was elected to the local government. The men were taken to jail in Green River. They were held there until a local jury refused to charge them with any crimes. The jury said that even though they questioned many witnesses, no one could name a single criminal act done by any known white person that day.

The people arrested as suspects were released a little over a month later, on October 7, 1885. When they were released, they were met by hundreds of people who cheered for them. No one was ever found guilty for the violence at Rock Springs.

Government and Diplomatic Issues

After the riot, the U.S. government was slow to make up for the massacre. In China, a leader in the Guangdong region suggested that Americans in China might be attacked in revenge. American diplomats in China reported that anti-American feelings were growing in Hong Kong and Canton. They warned their government that the massacre could hurt U.S. trade with China. They also said that British merchants and newspapers in China were telling the Chinese to "stand up for their oppressed countrymen in America."

The United States government agreed to pay for the damaged property. But they would not pay for the actual victims of the massacre. U.S. Secretary of State Thomas F. Bayard believed that the violence against Chinese immigrants happened because they did not try to fit into American culture. He also thought that racism against Chinese people mostly came from other immigrants, not from most Americans.

Because of the warnings from diplomats, Bayard asked the U.S. Congress to pay money to the victims. Congress provided US$147,748.74 as a payment. This money was given as a gift, not as a legal admission of fault for the massacre. This outcome was a small diplomatic win for China.

Wyoming's Governor, Francis Warren, called the riot "the most brutal and terrible outrage that ever occurred in any country."

Public Reaction

After the riot, many newspapers and important political figures spoke out. The New York Times strongly criticized Rock Springs. It said the city deserved the same fate as "Sodom and Gomorrah" (two cities from the Bible destroyed for their wickedness). The Times also criticized those who stood by and let the mob continue. However, newspapers in Wyoming, like the Cheyenne Tribune and the Laramie Boomerang, felt sympathy for the white miners. The Boomerang said it "regretted" the riot but found reasons for the violence.

Other publications also showed anti-Chinese feelings. The Chautauquan: A Weekly Newsmagazine described the Chinese as weak and defenseless. It said that murdering an "industrious Chinaman" was as bad as murdering women and children.

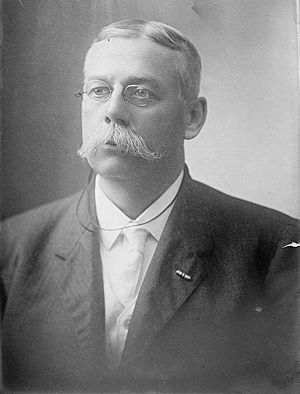

Knights of Labor leader Terence V. Powderly blamed the "problem" of Chinese immigration on the weaknesses of the 1882 Exclusion Act. He said that poor law enforcement, not the rioters, was to blame for the attacks. Powderly believed that Congress should fix the laws against Chinese immigration to prevent such incidents.

In December 1885, U.S. President Grover Cleveland spoke to Congress. He said that the United States wanted good relations with China. He stated that the government should do everything to treat the Chinese fairly and that the law must be strictly followed. He also said that "race prejudice is the chief factor to originating these disturbances."

Violence After Rock Springs

The Rock Springs massacre led to other attacks against Chinese people. These happened mostly in Washington Territory, but also in Oregon and other states. Near Newcastle, Washington, a group of white people burned down the homes of 36 Chinese coal miners. In the Puget Sound area, Chinese workers were forced out of communities and attacked in cities like Tacoma, Seattle, Newcastle, and Issaquah. These events were directly linked to the wave of violence that started in Rock Springs.

The anti-Chinese violence also spread to Oregon. Mobs forced Chinese workers out of small towns there in late 1885 and mid-1886. Other states also reported incidents. Even as far away as Augusta, Georgia, people expressed anger against the Chinese because of the Rock Springs massacre.

Why This Event Matters Today

Historians today see the Rock Springs massacre as one of the worst and most important examples of anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States. The riot was widely covered by newspapers like The National Police Gazette and The New York Times. Among all the anti-Chinese violence in the American West, the Rock Springs massacre is considered the most well-known.

Today, almost all historians agree that race prejudice was the main reason for the riot. However, some earlier works focused more on economic reasons, like competition for jobs. While job competition played a part, it is generally seen as less important than racism. The use of Chinese workers by the railroad during a strike in 1875 caused a lot of anger among white miners. This anger grew until the Rock Springs massacre.

Some people also believed that the Chinese refused to fit into American culture. This idea was common in the past and still influences some views of the event today.

Today, Rock Springs has a population of nearly 20,000 people. The area where the army post once stood is now part of the city. The area that was once Chinatown now has a public elementary school built over part of it. The places in Rock Springs connected to the massacre have been covered by the city's growth.

|

See also

In Spanish: Masacre de Rock Springs para niños

In Spanish: Masacre de Rock Springs para niños