Shasta people facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 653 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

( |

|

| Languages | |

| English, formerly Shastan languages | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Okwanuchu |

The Shastan peoples are groups of Native American people who lived in the Klamath Mountains. They traditionally lived near rivers like the Klamath, Salmon, Sacramento, and McCloud rivers. Today, their lands are part of Siskiyou, Klamath, and Jackson counties.

Experts usually divide the Shastan peoples into four language groups. These groups, including the Shasta (also called Kahosadi), Konomihu, Okwanuchu, and Tlohomtah’hello "New River" Shasta, lived in villages often close to water. Their villages were usually small, with just one or two families. Larger villages had more families and buildings for the whole community.

The California Gold Rush in the late 1840s brought many outsiders to California. This was a very hard time for the Shasta. Thousands of miners came to their lands, digging for gold along the rivers. Conflicts started because the newcomers did not respect the Shasta people or their homeland. New diseases and fighting against the Americans quickly reduced the number of Shasta people.

Some Shasta people from Bear Creek fought in the Rogue River Wars. They helped the Takelma people. But then, they were forced to move to the Grande Ronde and Siletz Reservations in Oregon. In the late 1850s, Shastan peoples in California were also forced from their homes and sent to these same distant reservations. By the early 1900s, only about 100 Shasta people were left. Today, some Shasta descendants still live at the Grand Ronde and Siletz Reservations. Others live in Siskiyou County at the Quartz Valley Indian Reservation or Yreka. Many former Shasta members have also joined the Karuk and Alturas tribes.

Contents

What Does the Name "Shasta" Mean?

Before Europeans arrived, the Shastan peoples probably did not use the name "Shasta" for themselves. The Shasta people called themselves "Kahosadi", which means "plain speakers." White settlers used different spellings like Chasta, Shasty, and Sasti.

An early expert, Dixon, thought the name "Shasta" came from a respected man in Scott Valley named Susti or Sustika, who lived until the 1850s. Another expert, Kroeber, agreed with this idea. However, some believe the nearby Klamath people might have used a similar word for the Shasta.

In 1814, a group called Shatasla was mentioned. Some thought this was an old version of "Shasta." But other experts disagree, saying it was likely related to the word Sahaptin.

How Were Shasta Communities Organized?

The Shasta were the largest group among the Shastan speakers. Their lands stretched from Ashland in the north to Mount Shasta in the east, and west to Seiad Valley. This area had four important rivers: the Klamath River, Shasta River, Scott River, and Bear Creek. Each river area had a different group of Shasta people with their own customs and ways of speaking.

Shasta villages often had only one family. In bigger villages, there were leaders called headmen. These headmen had many jobs. They were expected to encourage people to live peacefully, be kind, and work hard. To be a headman, a person usually had to be wealthy. This was because they were expected to use their wealth to help settle arguments within their village or with other villages. Headmen did not fight in raids against enemies. Instead, they talked with enemy leaders to make peace.

Each of the four Shasta groups had its own headman. It is believed that the position was passed down through families. If there was a difficult problem, the headman from the Ikirukatsu group would often help solve it.

Other Shastan Groups

Three other groups who spoke Shastan languages lived near the main Shasta people. These were the Okwanuchu, who lived near the upper Sacramento and McCloud rivers. The Konomihu and Tlohomtah’hoi Shasta lived near the Salmon River. There is not much information recorded about these groups. They each had very small territories.

The Shasta called the Konomihu "Iwáppi." The Konomihu called themselves "Ḱunummíhiwu." They lived along parts of the Salmon River. About seventeen villages were known in Konomihu territory. Their political system was different from the Shasta. They did not have appointed or inherited village leaders. We do not know much about how the Konomihu interacted with their neighbors. However, they often married people from the Irauitsu Shasta group, even though they sometimes had disagreements. The Irauitsu Shasta were also important trading partners. The Konomihu traded their buckskin clothes for abalone beads.

We do not know what the Tlohomtah’hoi Shasta called themselves. The Shasta people likely called them "tax·a·ʔáycu." The Tlohomtah’hoi Shasta mostly lived in the Salmon River basin, but some lived near the New River. There were at least five known settlements.

Very little information has been saved about the Okwanuchu people. We do not know where the name "Okwanuchu" came from. They often married people who spoke the Achomawi language.

How Many People Lived Here?

Estimates for how many Shasta, Okwanuchu, New River Shasta, and Konomihu people lived long ago have changed a lot. In the 1990s, some Shasta people said that over 10,000 Shastan people lived in the 1840s. One expert, Alfred L. Kroeber, thought there were about 2,000 Shasta people in 1770 and another 1,000 from the related groups. Another expert, Sherburne F. Cook, later suggested there were about 5,900 total Shastan people. By 1910, Kroeber estimated only about 100 Shasta people were left.

Daily Life and Culture

What Did They Eat?

The Shastan peoples ate foods found in their local area. Many plants and animals in Shasta lands were also found nearby. The Shasta and other groups in the region commonly gathered and used these foods. There were many game animals in Shasta territories, which sometimes led to conflicts with other Native Californians who wanted the meat and furs. The Shasta used controlled fires to clear undergrowth in forests. This helped grow useful plants that were often food sources.

Fishing happened in spring, summer, and autumn. The Karuk people's White Deerskin dance told the Shasta when it was okay to eat fish. This dance happened in July. Before the dance, Coho salmon could be caught and dried, but not eaten. Rainbow trout had to be released before the Karuk dance. Not following this rule was seen as a serious offense. The Shasta did not use spears much for fishing. They built fires at fish traps to help with night fishing. Their fishing nets were very similar to those made by the Karuk and Yurok. They caught catfish and crawfish using bait on lines, then scooped them up with thin baskets.

California mule deer were hunted in several ways. In autumn, hunters would use controlled fires to make deer run into traps at salt licks. Shasta people also chased deer into nooses tied to trees. Sometimes, dogs were trained to chase deer into creeks, where hidden hunters would kill them with arrows. There were rules about who owned the deer. For example, the person who killed the deer got its skin and back legs. Other rules made sure the meat was shared fairly and set times for hunting.

Smaller animals were also important food sources. Women and children collected mussels from the Klamath River by diving for them. In autumn, when the river was low, mussels were easy to find along the banks. Once enough mussels were gathered, they were steamed in earth ovens. Then, their shells were opened, and the meat was dried in the sun for later use. Grasshoppers and crickets were eaten by some Shasta groups. Shasta men would set parts of grasslands on fire. After the fires died down, they collected the cooked grasshoppers and dried them. Sometimes, grasshoppers were ground into a fine powder with grass seeds.

Acorns were a very important food in Shasta cooking. They came from trees like the Canyon Oak, California Black Oak, and Oregon White Oak. After removing bitter substances, the acorns were made into a dough. Black Oak meal was preferred over White Oak meal. Canyon Oak acorns were often buried until they turned black before being cooked. Nuts from Sugar pines were often steamed, dried, and stored. Pitch from the Ponderosa pine was ground into a powder and eaten or used as chewing gum. Many fruits were picked when ripe and often dried, including Chokecherries, Whiteleaf manzanita berries, Pacific blackberries, San Diego raspberries, and Blue elderberries.

Flower bulbs were gathered each season to add to their food supply. Camas roots were commonly collected. Plants from the calochortus group, called "ipos" by the Shasta, were highly valued. After peeling, ipos roots were eaten raw or dried in the sun and stored. Dried ipos was used in many Shasta dishes. Guests were often given small servings of serviceberries and dried ipos while the main meal cooked. A popular dish was powdered ipos root mixed into manzanita cider. Another eaten flowering plant was Fritillaria recurva, called "chwau." Its bulbs were roasted or boiled.

Where Did They Live?

Shasta houses were similar to those of the Hupa, Karuk, and Yurok peoples. The Shasta built strong, permanent houses for winter. These homes were built in the same spots every year, usually near a creek. Shasta winter villages along the Klamath River often had only three families. Other Shasta villages usually had more families.

Building a winter house started by digging a pit. These pits were usually rectangular or oval, about 16 feet by 20 feet, and about 3 feet deep. After clearing the area, strong wooden poles were placed in the corners to support the roof. More wooden supports were added throughout the house. The pit walls were covered with cedar bark, and the roof was made of sugar-pine or cedar wood.

The okwá'ŭmma, or "big house," was a special building in larger Shasta villages. It was a big pit, up to 26 feet wide, 39 feet long, and 6.6 feet deep. It was built like the winter homes. These big houses were mainly used for community gatherings, religious ceremonies, and dances. If a villager had too many guests for their own house, they could ask to use the okwá'ŭmma. These big houses were owned by an important person, often the headman, and built with help from the community. They were rare; only about three existed along the Klamath River. Male relatives inherited the structure. If only female relatives were left, the house was burned down.

Konomihu homes changed with the seasons, like the Shasta. In spring and summer, during the salmon runs, they used huts made from plant branches. In autumn, they left these huts for bark houses while hunting deer. Their winter houses were different from the Shasta, Karuk, and Yurok. While partly underground, their houses were round, 15 to 18 feet wide, with sloped, cone-shaped roofs.

What Did They Make?

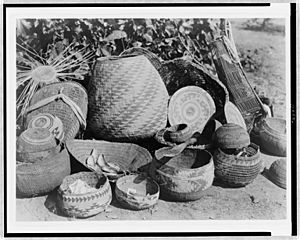

Baskets were very important for Shasta households. They mostly bought their baskets from the Karuk people. The Konomihu also bought most of their baskets from other groups. Shasta-made baskets used plant materials from Ponderosa pine, California hazelnut, willow trees, Bear grass, and Five-fingered fern. Their basket designs were influenced by the nearby Hupa, Karuk, and Yurok peoples. The Shasta made dyes to decorate baskets and other personal items. Red and black dyes were most common, made from acorns and alder bark.

Ropes, cords, mats, nets, and clothes were mostly made from Indian hemp. In winter, snowshoes were often needed to travel. These were made mainly from deer hide with the fur left on. Dentalium shells were important to the Shasta. They were used as decorations on clothing and as a way to trade for goods. The Konomihu made buckskin leggings, robes, and skirts. These were painted with black, red, and white patterns and decorated with dentalia and abalone beads. The Okwanuchu made wooden pipes similar to those made by the Wintu. Raccoon and fox furs were used to stay warm in the cold mountain winters. Moccasins were kept waterproof and soft with oils from deer, fish, cougars, or bears.

In 1845, Charles Wilkes described Shasta weapons: "Their bows and arrows are beautifully made. The bows are made of yew wood, about three feet long, flat, and one and a half to two inches wide. They are neatly backed with animal tendons and painted. The arrows are over thirty inches long; some were made of a fine-grained wood, while others were of reed. They had feathers for five to eight inches, and the sharp heads were beautifully made from obsidian... Their quivers are made of deer, raccoon, or wild-cat skin. These skins are generally whole, left open at the tail end."

How Did They Decorate Their Bodies?

Body decoration was common among the Shasta. They used red, yellow, blue, black, and white dyes in their art. These dyes came from plants and natural clay. Body painting was mainly used by spiritual leaders (shamans) and those getting ready for war. Warriors often used white and black colors for war. Shamans painted red geometric patterns on their buckskin clothes.

Older women created permanent tattoos using small obsidian flakes. Women's tattoos were usually several vertical lines on the chin, sometimes extending to the corners of the mouth. Women without chin tattoos were seen as less attractive. For men, tattoos were important for trading. Lines on their hands or arms were used to measure dentalia and beads. Septum piercings held long dentalia shells or decorated feathers. Ear piercings held groups of dentalia.

How Did They Fight?

Warfare usually involved small raids. Leaders for these attacks were chosen by the raiding party members. Armed groups were formed to respond to aggression or violence against villagers. Prisoners taken in raids were usually not killed. Instead, they were allowed to live as slaves. However, slavery was not very common among the Shasta and was not seen as a good practice. Dixon noted that "persons owning slaves were said to be, in a way, looked down upon."

Shasta warriors wore protective gear when going into conflict. Stick armor was preferred over elkhide armor. Stick armor was made from serviceberry trees and tightly woven with twine. Head coverings were made from elk hide, sometimes in several layers. Shasta women could join in preparing for attacks and even participate in battles. Dixon recorded that women would use obsidian knives to try to disarm or destroy enemy weapons.

Warriors from the Klamath River and Ahotireitsu Shasta groups often fought against the Modoc. These fights are thought to have been the most violent for the Shasta. While disputes and raids happened with the Wintu, they were not as destructive as the wars with the Modoc. Attacks on Wintu and Modoc villages included burning down the settlement. This was not done in raids between Shasta villages.

Neighbors and Trade

The Shasta lived where several major cultural regions met. This was reflected in their neighbors, who had different ways of life and goods. To the southwest, on the lower Klamath River, were the Karuk, Yurok, and Hupa. South of Shasta territory lived the Wintu. To the east and southeast were the Achomawi and Atsugewi, who had some language connections with the Shasta.

Klamath River Societies

The Karuk were known as "Iwampi" by the Shasta, meaning "down the river." The Karuk and Yurok influenced many parts of Shasta society and were their main trading partners. These groups were very similar to the Shasta.

The Shasta generally respected Karuk culture, especially their handmade items. Shasta traders would bring goods like preserved foods, animal furs, and obsidian blades downriver. The Shasta wanted items like Tan Oak acorns, Yurok-made redwood canoes, various baskets, seaweed, dentalia, and abalone beads. The Karuk were also the main source of dentalia for the Konomihu. Baskets and hats used by the Shasta were mostly bought from these Klamath River nations.

Takelma People

The exact border between Shasta and Takelma lands to the north has been debated by experts. Shasta people told one expert, Roland B. Dixon, that they used to live in the Bear Creek Valley. Another expert, Edward Sapir, suggested that both the Shasta and Takelma used this area. Alfred Kroeber believed Shasta lands reached as far north as modern Trail, Oregon.

Based on old accounts, it seems that in the early 1800s, the southern Bear Creek valley was used by both Shasta and Takelma peoples. The higher parts of Neil and Emigrant Creeks, and the northern Siskiyou slopes near Siskiyou Summit, were Shasta areas. Even with conflicts over the Bear Creek Valley, the Takelma were active trading partners with the Shasta and a major source of dentalia shells.

Modoc and Klamath Peoples

The Modoc, known as the "Ipaxanai" by the Shasta (meaning "lake"), were traditionally not highly regarded by the Shasta. A Shasta person once said, "How could you settle anything with them? They didn't have any money." There was some trading between the Shasta and the Klamath, but it was rare. Shasta-made beads were traded for animal furs and blankets.

Both the Modoc and Klamath got horses in the 1820s. This made them much stronger in battle. They began attacking their southern and western neighbors. Both the Ahotireitsu and Klamath River Shasta groups were targets of Modoc raids for slaves.

Achomawi and Atsugewi Peoples

The Achomawi and Atsugewi speakers lived to the east in the Pit River basin. Not much is recorded about Shasta interactions with them. The Shasta were the main source of dentalia for both these groups. There was some direct contact with the Atsugewi, but it was probably minimal. Atsugewi people said they shared many cultural traits with the Shasta, especially their religion, stories, social organization, and customs. The Madhesi group of Achomawi sometimes had conflicts with the Shasta. Villages near modern Big Bend were sometimes raided by Shasta warriors.

Wintu People

Wintu groups near modern McCloud, California and in the Upper Sacramento Valley had the most contact with the Shasta. While fights did happen with Wintu speakers, it was not as common as conflicts with the Modoc. These conflicts led the Wintu to call the Shasta "yuki," meaning "enemy."

Despite occasional fights, there was some trade and cultural exchange. The Wintu were a source of Tan oak acorns and abalone beads. The Shasta were the main distributors of dentalia to the Wintu, along with some obsidian and buckskin. Both the Shasta and Wintu made a cider from Manzanita berries. People from both cultures were inspired by each other's handmade goods. Ahotireitsu Shasta thought Wintu clothing was stylish and made hats from Indian hemp in their style. Upper Sacramento Valley and McCloud Wintu admired the smooth hats used by the Shasta. The Wintu copied these twine hats, often using material from Woodwardia ferns.

Early 1800s: First Encounters

The Shasta word for white people, "pastin," came from "Boston," a word used in the Chinook Jargon for Americans. The Shasta were far from the Spanish colonies in California. When Mexico gained independence, Mexican officials took control of the Spanish settlements. This did not change much for the Native peoples north of the Californian ranches, as they kept their lands and protected position. Around the 1820s, the Modoc and Klamath peoples got horses from groups to the north. With horses, they began attacking the Shasta, Achomawi, and Atsugewi for property, food, and slaves to sell. The Shasta fought back, but they did not get many horses themselves.

The first recorded meeting between the Shasta and Europeans happened in 1826. An expedition from the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) led by Peter Skene Ogden came to trap beavers in the Klamath Mountains. Ogden's group was welcomed by the Shasta. The HBC continued to send expeditions through Shasta lands, following the Siskiyou Trail.

The next known interaction with white people was not peaceful. In autumn 1837, a group of settlers from the Willamette Valley traveled through Shasta lands. They were driving hundreds of cattle. The Shasta welcomed the outsiders, even though communication was difficult. Philip Leget Edwards wrote that the cattle drivers were "at their mercy, but they have offered no injury to ourselves or property." A Shasta boy, about ten years old, traveled with the settlers for some time. As the group continued north, some of the cattle men talked about killing Native people. Two men, William J. Bailey and George K. Gay, had been injured fighting the Takelma people before. They decided to attack the Shasta for revenge. They found a Shasta man and shot him to death. They also tried to kill the Shasta youth who had joined them, but he escaped. The leader, Ewing Young, was very angry about the murder, but most of the group approved. Bailey and Gay were not punished.

Several years later, in 1841, a part of the United States Exploring Expedition visited the Klamath Mountains. They traveled through Shasta lands, generally following the Siskiyou Trail. They visited a Shasta village where people gave them salmon and sold them bows and arrows for trade goods. The villagers showed their archery skills by hitting a button from 20 yards away. After this peaceful visit and trade, the explorers left Shasta lands.

The Discovery of Gold

Contact with Europeans became much more frequent by the 1840s. The United States took control of California during the Mexican–American War. The California Territory was established in 1849, but much of the land was still held by Native peoples. Shasta County was formed in 1850. In 1852, Siskiyou County was created from the northern parts of Shasta County. This new American area included the Shasta homelands in California.

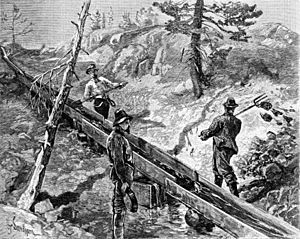

The promise of gold brought hundreds of thousands of outsiders during the California Gold Rush. The new miners and settlers often used violence against Native Californians. Miners moved north from Sutter's Mill looking for more gold. In 1850, gold was found on the Trinity and Klamath rivers. In the Shasta heartland, gold was found along the Salmon, Scott, and upper Klamath rivers in the next two years. Miners founded towns like Scott Bar and Yreka near these new gold sources. Miners did not like the Shasta, seeing them as warlike.

By August 1850, over 2,000 miners were looking for gold on the Klamath and Salmon rivers. Over a hundred miles of the Klamath River had been searched, and parts were taken over by mining operations. Advertisements appeared in newspapers, encouraging Americans to go north for wealth. Besides mining, white settlers also cut down forests to sell wood. By April 1851, a thousand acres of the Shasta River had been prospected. Scott River was said to have "the richest mines in all California." Many miners came to the northern region.

As the number of non-Native people grew, some considered wiping out the Native population. Miners argued that Native people along the Klamath River blocked access to gold. They were seen as "the only obstacle to complete success in those mines." Some newspapers suggested that Native people "must soon be removed by the Government Agents, or be exterminated by the sword of the whites." Violence and murder against Native people were often promoted as the only way to stop their "thieving and other annoying habits." Violence began across the Klamath River in summer 1850. In August, it was reported that miners had killed fifty to sixty Hupa people and burned three of their villages. In October, at the meeting of the Shasta and Klamath rivers, miners killed six Shasta people.

Government Efforts for Peace

In 1848, the Indian Superintendency reported to Congress about Native populations on the Pacific Coast. They suggested hiring new Indian agents. In 1850, William Carey Jones reported that Spanish and Mexican law did not recognize Native people's right to own their lands. After California became an American state, the topic of relations with its Native peoples came up in the Senate. Some argued that Native people had legal rights to their lands and should be paid for their losses. Others disagreed.

In September, the Senate passed two bills to create Federal policy with California Natives. Three commissioners were allowed to make treaties with them. Redick McKee, O. M. Wozencraft, and George W. Barbour were appointed and started talks in 1851. They did not know much about California Natives or how their societies used their lands. The Commissioners divided California into three areas to cover all the Native groups. McKee was assigned to make treaties with Native peoples in Northern California. He made agreements in Humboldt Bay and the lower Klamath River. In September 1851, he arrived in Shasta territory.

Local Conditions for a Treaty

McKee visited the Shasta territories, especially the Shasta and Scott Valleys. He decided that only the Scott Valley could support a reservation and the farming needed to feed the Shasta. This was because there was not much good farming land in the Klamath Mountains. Better areas were in Oregon. The Shasta wanted to keep all of Scott Valley for their reservation. American settlers from Scott Bar and Shasta Butte City also wanted the valley. Federal officials asked them what they wanted in a treaty with the Shasta. They wanted all Shasta people moved to a reservation at the headwaters of the Shasta River.

The Treaty Agreement

The terms McKee wrote for the agreement were not very popular with either the Shasta or the American settlers. The reservation was placed in Scott Valley, but most of the valley would stay with the settlers. The location of the Shasta reservation was accepted, though reluctantly, by most American settlers. Some had bought expensive land from other Americans. They expected to be paid by Congress or the Indian Department for their properties within the reservation.

The treaty area for the reservation was estimated by McKee to have four or five square miles of farmland. The Shasta were promised to receive "free of charge" 20,000 pounds of flour, 200 cattle, many clothes, and household goods from the Federal government in 1852 and 1853. Money was to be set aside by Congress to hire a carpenter, farmers, and teachers on the reservation. Gold prospecting along the Scott River was allowed for two more years. Any other mining operations within the reservation had one year to continue.

At the end of the talks, a bull was given to the Shasta. A celebration was held late into the evening. George Gibbs recorded the day the treaty was formally signed: "In the morning, November 4th, the treaty was explained carefully as drawn up and the bounds of the reservation pointed out on a plat. In the afternoon it was signed in the presence of a large concourse of whites and Indians, with great formality."

Allegations of Poisoning

Some accounts from Shasta people say that three thousand Shasta were at the ceremony. They reported that American officials served them beef poisoned with strychnine. Survivors told of spending weeks finding the dead. Only about 150 Shasta were said to have survived.

Why the Treaty Failed

The 18 treaties negotiated by McKee and the other commissioners were rejected by the California legislature. McKee argued that the reservations were designed to give Native people parts of their traditional lands while keeping gold-rich areas open. He said the commissioners always talked with local American settlers and miners when setting reservation borders. He argued that unless someone could "propose a more humane and available system," the reservations had to be accepted by the California Government. However, the state rejected all treaties and asked its representatives in Washington, D.C., to lobby against them.

President Millard Fillmore and other officials supported the treaties. They were sent to the Committee on Indian Affairs in June 1852. After a private meeting, the treaties were rejected. One reason suggested was that the large amount of land set aside (about 11,700 square miles, or 7% of California) and the money needed made the agreements unpopular in Congress. One expert, Heizer, concluded that the treaty process "was a farce from beginning to end..."

Ongoing Conflicts

Violence against the Shasta continued after the agreement with McKee. On January 18, 1852, three American men attacked and killed a Shasta person without reason on Humbug Creek. This caused panic among the local Shasta, who fled to the mountains. This killing also caused panic among the miners, who feared it would lead to conflict with the Shasta. McKee was asked to return and help. Two of the murderers were caught by miners. The family of the slain man was given six blankets as payment.

In July 1852, a group of miners found and killed fourteen Shasta people in Shasta Valley. This was in revenge for the murder of a white man. This increase in violence continued to reduce the number of Shasta. Their actions against white violence were to protect "their communities from assault, abduction, murder, massacre, and, ultimately, obliteration."

In January 1854, Americans in Cottonwood formed an armed group called the "Squaw Hunters." That month, they went to a nearby cave where over 50 Shasta were living. The Squaw Hunters attacked the Shasta, killing 3 children, 2 women, and 3 men. Afterward, they falsely claimed the Shasta were preparing to attack Americans. This rumor caused panic among settlers. Twenty-eight men gathered to attack the cave. In the fight, four Americans and one Shasta died. Federal troops from Fort Jones and local volunteers gathered near the Klamath River. In total, about fifty armed Americans were present. More forces arrived with a howitzer, which was fired at the cave many times. Representatives of the Shasta leader known as "Bill" asked for peace and said they were innocent. Military officials agreed that the Shasta were innocent. American settlers were blamed for the violence. The decision to stop fighting with Bill's people was unpopular with local settlers.

In late April 1854, a group of miners found and killed 15 Shasta. These murders were in revenge for some stolen cattle.

In May 1854, a Shasta man was accused of attacking an American woman. Fort Jones ordered the man to be captured and taken to authorities in Yreka. The accused man was not from Bill's group. Bill asked for a guarantee that the man would not be executed. Fort Jones said this was not possible. The commanding officer declared that if the man was not delivered soon, all Shasta would be held responsible. A large group of "De Chute" (likely Tenino) Native people visiting the area were threatened to be used in military actions against the Shasta. Leaders from the Irauitsu group supported capturing the man but also did not want him executed.

The accused Shasta was eventually taken to authorities in Yreka. On May 24, while returning to Yreka, the Shasta group was attacked on the Klamath River by American settlers and "De Chutes." The American officer told the Shasta to flee while he tried to talk to the attackers. The armed men refused to let the Shasta leave peacefully and shot at them. Two Shasta were killed instantly, and three were seriously injured.

On May 17, 1854, some Shasta warriors attacked a group of mules in the Siskiyou Mountains. Two Americans were leading the mules. One was killed, and the other escaped. Five horses and a mule were taken by the Shasta.

Rogue River Wars

The Irkirukatsu Shasta joined their Takelma neighbors in fighting against American settlers during the Rogue River Wars. New settlers started farms across the Rogue Valley in 1852 and 1853. Open meadows were plowed and fenced. Oak forests were cut down for building supplies and more farmland. Livestock like pigs dug up and ate the bulbs and roots of important flowering plants. These actions quickly destroyed many food sources for the Native people, including camas, acorns, and grass seeds.

A group of 150 to 300 Shasta gathered in the upper Rogue River basin in the winter of 1851-1852. They had gathered to settle a dispute over a woman. The American witness thought it was a "war expedition." However, the peaceful end to the matter, with payment, followed traditional Shasta ways of solving problems.

In early August 1853, a settler named Edwards was found killed in his cabin. This death caused a strong reaction from American settlers. Militias were formed to attack any Native people in the Rogue River basin without distinction. About a month before, Edwards had visited a Dakubetede settlement and taken a Shasta slave. The kidnapping was accepted by Americans, and requests for payment from the former slave owner were ignored. People in Jacksonville at the time thought this dispute caused the murder. The Irkirukatsu Shasta were especially targeted because they were seen as unwelcoming and aggressive towards American settlers. They received help from some Klamath River Shasta who had been forced from their homes by miners.

Eventually, the Shasta and Takelma were forced to accept being moved from the Rogue Valley. American officials met with the leaders of the Irkirukatsu Shasta and others on November 18, 1854. The "Chasta Treaty" was signed, but its terms were not clear to the Native leaders. The treaty said that the Federal government would pay for and staff several facilities on the reservation where the Oregon Shasta and their neighbors would be moved. This included a hospital, a schoolhouse, and two blacksmith shops.

Life on the Reservation

Life on the reservations was a difficult change for the Shasta. In November 1856, the Grand Ronde reservation had about 1,025 Native people, with 909 being Takelma or Shasta. On September 21, 1857, a federal official visited the Siletz Reservation. He estimated there were 544 Shasta and Takelma people there. The Superintendent, James Nesmith, reported in 1858 that some parts of the 1854 "Chasta Treaty" had not yet been put into action. Once moved to the Siletz Reservation, the promised blacksmiths, school teachers, and medical officials had to be shared among all Native people living there, not just those who signed the "Chasta Treaty."

Images for kids

-

Dentalium shells were brought in from the Takelma, Karuk, and Yurok. They were used by the Shasta in personal adornments, artistic additions to clothing or as a trading medium.

See also

In Spanish: Shasta (tribu) para niños

In Spanish: Shasta (tribu) para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |