Tenino people facts for kids

The Tenino people, also known as the Warm Springs bands, are Native American groups from North-Central Oregon. They speak a language called Sahaptin. Historically, they lived in specific areas within Oregon.

The Tenino people included four main groups:

- The Tygh (or "Upper Deschutes")

- The Wyam (or "Lower Deschutes"), also called "Celilo Indians"

- The Dalles Tenino (or "Tenino proper")

- The Dock-Spus (or "John Day")

These groups moved between winter camps and summer camps, often near the Columbia River. In 1855, they signed a treaty with the United States government. Today, the Warm Springs bands are part of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. They live on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation in Central Oregon.

Contents

A Look at Tenino History

Who Were the Tenino Bands?

The Tenino people were made up of four main local groups:

- The Dalles Tenino: They had summer villages near the Fivemile Rapids Site on the Columbia River. Their winter village was at Eightmile Creek. The name "Tinainu" was used for this group and for all the Tenino people.

- The Tygh (or "Upper Deschutes"): Their main summer village was on the Upper Deschutes River. Their winter village was near today's Tygh Valley, Oregon. They had three smaller village groups.

- The Wyam (or "Lower Deschutes"), also known as "Celilo Indians": Their summer village was at Celilo Falls on the Columbia River. This place was called Wyam, meaning "echo of falling water." Their winter village was on the Lower Deschutes River.

- The Dock-Spus (or "John Day"): They had two summer villages on the Columbia River. Their winter villages were on both sides of the John Day River.

These groups spent winters inland where they had water and fuel. In summer, they moved to the Columbia River for fishing.

Tenino Language and Neighbors

The Tenino people spoke a dialect of the Sahaptin language. This language was also spoken by the nearby Umatilla people. Other tribes in the area spoke different languages. For example, the Wasco and Wishram people to the northwest spoke a Chinookan language. The Molala people to the west spoke Waiilatpuan. The Northern Paiute to the south spoke a form of Shoshoni.

The Tenino people mostly lived peacefully with their neighbors. They remembered one big battle with the Molala, which pushed the Molala across the Cascade Mountains. They also had a short fight with the Klamath, who were usually good trading partners. The Northern Paiute were sometimes enemies, and conflicts happened between them.

How the Tenino Lived: Economy

Before the 1800s, the Warm Springs bands moved around a lot. They did not farm or raise animals for food. Instead, they relied on fishing for salmon, hunting wild animals, and gathering wild plants.

Men did most of the hunting and fishing. They also made tools from stone, bone, or animal horns. Men cut down trees for firewood and built the winter houses. They also made dugout canoes for traveling on the rivers.

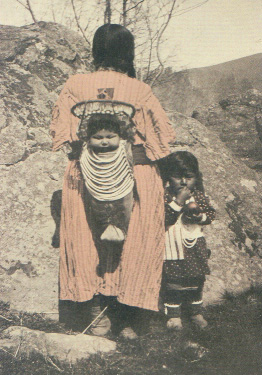

Women were in charge of preserving meat and fish by drying or smoking them. They also gathered most of the plant foods, like berries, roots, acorns, and pine nuts. Women cooked for their families and made or fixed clothing and bedding. They also made thread, rope, baskets, bags, and mats.

Women were usually the main traders with other tribes. In late summer and fall, groups of men would also go out to trade. The Tenino people traded dried salmon, fish oil, and animal furs. They received items like baskets, horses, buffalo hides, feathers, and shells.

The Warm Springs bands lived in family groups, not in one big communal house. Each family had its own homes. In winter, from November to March, each family had two houses. One was an oval dugout lodge covered with earth for sleeping. The other was a rectangular house above ground, covered with mats, used for cooking and daytime activities. In summer, from April to October, families moved to the river. They built temporary rectangular houses with poles and mats. Half of these houses were for sleeping, and the other half was a covered area for preparing salmon.

Tenino Culture and Festivals

The Tenino people held special festivals to celebrate the first foods of the new year. Every April, a group would go to catch fish and gather wapato roots. This was for a big festival held by most of the Tenino groups at the Dalles Tenino village. The Dock-Spus band celebrated separately. This "First Fish" ritual was common among many Native American peoples of the Pacific Northwest and Columbia River plateau.

During the First Fish ritual, a person who knew special songs and words would catch the ceremonial fish. The fish was never allowed to touch the ground. It was placed on a mat, cut with a traditional knife, cooked in a special way, and shared by certain tribal members. After eating, the bones were thrown back into the water. This was so dogs or other animals would not eat them. The meal was followed by traditional songs and dances. People believed that the soul of the First Fish would tell other salmon how respectfully it was treated. This would encourage more salmon to come upstream.

After this festival, about half the families would go hunting to the south. The rest stayed at the summer village to catch and dry fish.

Every July, the whole community gathered again. This time, they celebrated summer foods like berries and venison. After this festival, the community would split again. Some stayed to catch and smoke salmon, while others gathered nuts and berries and hunted. In October, they gathered reeds to make mats. Then, the temporary summer village was taken down, and everyone returned to their permanent winter village inland.

Meeting European-Americans

The Lewis and Clark Expedition first met the Tenino people in October 1805. Several Tenino helped the explorers move their boats and supplies around the difficult Celilo Falls. The explorers spent a whole day moving their things, while many people watched.

Near Celilo Falls, explorer William Clark saw how the Tenino people dried salmon to preserve it: "After being sufficiently dried, it is pounded fine between two stones. Then, it is put into a basket made of grass and rushes, about two feet long and one foot wide. This basket is lined with dried salmon skin. The fish is pressed down as hard as possible. When full, they close the basket with fish skins. They then place these baskets in a dry spot, with the tied part facing up. They usually set seven baskets close together, with five on top. They secure them with mats, which are wrapped around them and tied fast, then covered with more mats. These 12 baskets, each weighing 90 to 100 pounds, form a stack. The people told me that fish preserved this way can stay good for several years. They also told us that large amounts are sold to white people who visit the mouth of this [Columbia] river, as well as to other Native people downstream."

Warm Springs Reservation is Formed

On June 25, 1855, the United States government created the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. This was part of a treaty with the four Tenino bands and three bands of the nearby Wasco people. The Dalles Tenino, Tygh, Wyam, and Dock-Spus groups had to move from their traditional lands to the new reservation in 1857. The Wasco bands and other Chinookan-speaking neighbors followed in 1858. By 1858-59, about 850 Tenino people had moved there. About 160 members of the Wyam and Dock-Spus bands had not yet moved.

This new reservation was on land that traditionally belonged to the Northern Paiute. For several years, the Northern Paiute sometimes raided the reservation for horses and other items.

Besides the reservation, the Tenino people have a treaty right to use lands around Government Camp, Oregon on Mount Hood. The Mt. Hood Tribal Heritage Center, called Wiwnu Wash, opened at the Mount Hood Skibowl in 2012.

The Tenino People Today

Today, the Warm Springs bands are part of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. As the 20th Century ended, the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs had a total of 3,405 members. This includes descendants of the Tenino, Wasco, and Northern Paiute tribal groups.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |