Ocean current facts for kids

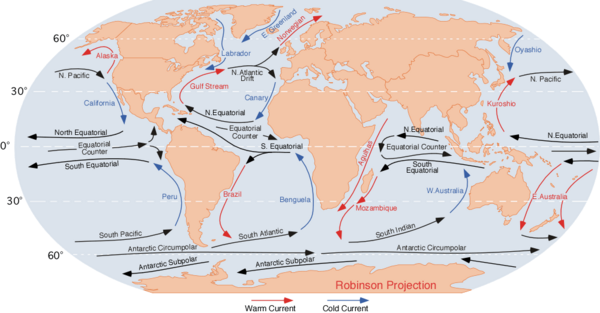

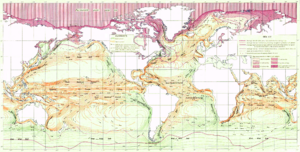

An ocean current is like a giant river of seawater that moves continuously in one direction. These currents are created by many things working together. These include wind, the Earth's spin (called the Coriolis effect), and differences in water temperature and how salty the water is. The shape of the ocean floor and coastlines also change how strong and where a current flows. Ocean currents mainly move water sideways across the ocean.

Ocean currents travel huge distances. Together, they form a "global conveyor belt" that plays a big role in shaping the climate of many places on Earth. Simply put, ocean currents affect the temperature of the areas they pass through. For example, warm currents flowing near cooler coasts make those places warmer. They do this by heating the sea breezes that blow over them.

A great example is the Gulf Stream. This warm current makes northwest Europe much milder than other places at the same latitude. Another example is Lima, Peru. Its cooler subtropical climate is different from nearby tropical areas because of the Humboldt Current. Ocean currents are patterns of water movement that affect climate zones and weather all over the world. They are mostly driven by winds and how dense (heavy) the seawater is. Many other things, like the shape of the ocean basin, also influence them. There are two main types of currents: surface currents and deep-water currents. Both are important for how ocean waters move across the planet.

Contents

What Makes Ocean Currents?

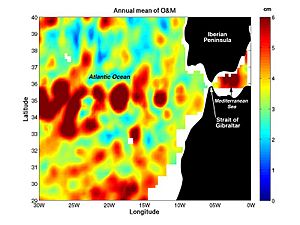

Ocean dynamics describe how water moves in the oceans. Ocean temperature and movement can be thought of in three layers. These are the mixed (surface) layer, the upper ocean, and the deep ocean. Ocean currents are measured in units called sverdrups (sv). One sverdrup means 1 million cubic meters (about 35 million cubic feet) of water moving per second.

Surface ocean currents are different from deep currents. They make up only about 8% of all ocean water. They are usually found in the top 400 meters (about 1,300 feet) of the ocean. They are separated from deeper water by changes in temperature and saltiness. These changes affect the water's density, which then defines each ocean area. Deep ocean water moves because of density and gravity. Cold, dense water sinks into deep ocean basins in very cold places. Surface currents are measured in meters per second (m/s) or in knots.

Wind-Driven Currents

Surface ocean currents are pushed by winds. Large, steady winds create major, lasting ocean currents. Winds that blow only sometimes or seasonally create currents that last for similar amounts of time. The Coriolis effect is very important in how these currents develop. The Coriolis effect makes currents flow at an angle to the wind. This causes them to form spirals that turn clockwise in the northern hemisphere and counter-clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. Also, the areas where surface currents flow can shift a bit with the seasons. This is most noticeable near the equator.

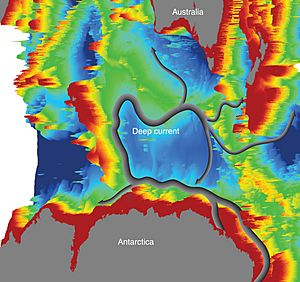

Deep Ocean Currents

Deep ocean currents are driven by differences in water density and temperature. This process is called thermohaline circulation. It's also known as the ocean's conveyor belt. These currents, sometimes called "underwater rivers," flow far below the ocean's surface. They are not easy to see. When ocean currents move a lot vertically (up or down), it's called upwelling (water rising) or downwelling (water sinking). An international project called Argo started studying deep ocean currents with underwater robots in the 2000s.

The thermohaline circulation is a big part of how the ocean moves. It's driven by global differences in density. These density differences are caused by heat from the sun and fresh water entering the ocean. The word thermohaline comes from thermo (meaning temperature) and haline (meaning salt content). Temperature and saltiness together decide how dense seawater is.

Wind-driven surface currents, like the Gulf Stream, travel towards the poles from the warm equatorial Atlantic Ocean. As they travel, they cool down. Eventually, they sink in high latitudes, forming what's called North Atlantic Deep Water. This heavy water then flows into the deep ocean basins. Most of it rises back up in the Southern Ocean. The oldest waters, which take about 1,000 years to travel, rise up in the North Pacific. This means there's a lot of mixing between ocean basins, making Earth's oceans a single global system. As these water masses travel, they carry energy (as heat) and materials (like dissolved substances and gases) around the world. So, how this circulation works has a big effect on Earth's climate. The thermohaline circulation is sometimes called the ocean conveyor belt or the global conveyor belt.

Where Ocean Currents Are Found

Here are some of the main ocean currents found in different parts of the world:

Currents of the Arctic Ocean

- Baffin Island Current

- Beaufort Gyre

- East Greenland Current

- East Iceland Current

- Labrador Current

- North Icelandic Jet

- Norwegian Current

- Transpolar Drift Stream

- West Greenland Current

- West Spitsbergen Current

Currents of the Atlantic Ocean

- Angola Current

- Antilles Current

- Atlantic meridional overturning circulation

- Azores Current

- Benguela Current

- Brazil Current

- Canary Current

- Cape Horn Current

- Caribbean Current

- East Greenland Current

- East Iceland Current

- Equatorial Counter Current

- Falkland Current

- Florida Current

- Guinea Current

- Gulf Stream

- Irminger Current

- Labrador Current

- Lomonosov Current

- Loop Current

- North Atlantic Current

- North Brazil Current

- North Equatorial Current

- Norwegian Current

- Portugal Current

- South Atlantic Current

- South Equatorial Current

- West Greenland Current

- West Spitsbergen Current

Currents of the Indian Ocean

- Agulhas Current

- Agulhas Return Current

- East Madagascar Current

- Equatorial Counter Current

- Indian Monsoon Current

- Indonesian Throughflow

- Leeuwin Current

- Madagascar Current

- Mozambique Current

- North Madagascar Current

- Somali Current

- South Equatorial Current

- Southwest Madagascar Coastal Current

- West Australian Current

Currents of the Pacific Ocean

- Alaska Current

- Aleutian Current

- California Current

- Cape Horn Current

- Cromwell Current

- Davidson Current

- East Australian Current

- East Korea Warm Current

- Equatorial Counter Current

- Humboldt Current

- Indonesian Throughflow

- Kamchatka Current

- Kuroshio Current

- Mindanao Current

- Mindanao Eddy

- North Equatorial Current

- North Korea Cold Current

- North Pacific Current

- Oyashio Current

- South Equatorial Current

- Subtropical Countercurrent

- Tasman Front

- Tasman Outflow

Currents of the Southern Ocean

- Antarctic Circumpolar Current

- Tasman Outflow

- Kerguelen deep western boundary current

Oceanic gyres (large systems of rotating ocean currents)

- Beaufort Gyre

- Indian Ocean Gyre

- North Atlantic Gyre

- North Pacific Gyre

- Ross Gyre

- South Atlantic Gyre

- South Pacific Gyre

- Weddell Gyre

How Currents Affect Climate and Ocean Life

Ocean currents are important for understanding marine debris (trash in the ocean). They also greatly affect temperatures around the world. For example, the ocean current that brings warm water to northwest Europe slowly stops ice from forming along the coast. This helps keep shipping lanes open. So, ocean currents play a key role in influencing the climates of regions they flow through.

Cold ocean currents that come from polar and sub-polar regions bring a lot of plankton. Plankton are tiny organisms that are vital for many sea creatures in marine ecosystems. Since fish eat plankton, you often find many fish where these cold currents are.

Ocean currents are also very important for spreading many forms of life. A good example is the life cycle of the European Eel.

Why Ocean Currents Are Important for People

Knowing about surface ocean currents can help ships save money. Traveling with the current reduces how much fuel ships need. In the past, when ships used sails, knowing about wind patterns and ocean currents was even more important. A good example is the Agulhas Current along eastern Africa. For a long time, this strong current made it hard for sailors to reach India. Today, sailors competing in around-the-world races use surface currents to go faster.

Ocean currents can also be used to make electricity. Places like Japan, Florida, and Hawaii are looking into test projects for this.

See also

In Spanish: Corriente marina para niños

In Spanish: Corriente marina para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |