SS California (1848) facts for kids

SS California, Pacific Mail's first ship on the Panama City to San Francisco route.

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | California |

| Laid down | 4 January 1848 |

| Launched | 19 May 1848 |

| Fate | Wrecked Pacasmayo Province, Peru 1895 |

| General characteristics | |

| Length | 203 feet (62 m) |

| Beam | 33.5 feet (10.2 m) |

| Draft | 14 feet (4.3 m) |

| Depth of hold | 20 feet (6.1 m) |

| Propulsion | 2 × 26 feet (7.9 m) dia. side paddle wheels |

The SS California was a very important ship in American history. It was one of the first steamships to sail in the Pacific Ocean. It was also the very first steamship to travel from Central America all the way to North America.

The ship was built for a company called the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. This company started on April 18, 1848. It was created by a group of merchants from New York City, including William H. Aspinwall. The California was the first of three steamships built to carry mail, passengers, and goods. These ships would travel between Panama and cities like San Francisco and Oregon.

Contents

Why the California Was Built

In the early days of the United States, the government usually didn't build roads or canals. They believed this was a job for private companies or individual states. However, the government could pay companies to carry mail. This was a way to help build important travel routes without directly building them.

Before 1848, Congress had already paid for mail ships to travel between Europe and the United States. Around 1847, another company, the U.S. Mail Steamship Company, won a contract. They would carry mail from East Coast cities and New Orleans to the Chagres River in Panama.

The Chagres River was the start of a difficult journey across the Isthmus of Panama. Travelers would get off their steamship on the Atlantic side. Then, they would go up the Chagres River for about 30 miles (48 km) in native canoes. After that, they would switch to mules to finish the 60-mile (97 km) trip. During the rainy season, this trail was often very muddy and hard to cross.

Building the Ship

The U.S. Mail Steamship Company sent its first steamship, the SS Falcon, from New York City on December 1, 1848. This was just before President James K. Polk officially announced the discovery of gold in California. When the Falcon reached New Orleans, many people wanted to travel on it. Other steamships and sailing ships soon joined the Falcon, all heading for Panama.

The SS California was built as part of a special mail contract from Congress in 1847. This contract was worth about $199,000. It was meant to set up regular mail, passenger, and freight service to the new territories of Oregon and California. The plan was for three steamships, each about 1,000 tons, to sail regularly (about every three weeks) between Oregon/California and Panama City. Panama City was the Pacific end of the trail across the Isthmus of Panama.

The job to build the California was given to William H. Webb in 1848. He was famous for building fast clipper ships. Ship designs for ocean-going steamships were already well-known from ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean.

The California was 203 feet (62 m) long and 33.5 feet (10.2 m) wide. It was 20 feet (6.1 m) deep and drew 14 feet (4.3 m) of water. It could carry 1,057 gross tons of weight. The ship had two decks, three masts, and a round back end. It could normally carry about 210 passengers. The California's keel (the bottom structure of the ship) was laid down on January 4, 1848. It was launched on May 19, 1848, and cost $200,082 to build.

The California was made from strong oak and cedar wood. Its hull (the body of the ship) was strengthened with diagonal iron straps. This helped it handle the force of its large paddle wheels. The ship's hull was a changed version of the popular clipper ship hulls of that time. It had three masts and sails, like a brigantine sailing ship. The sails were mostly for extra power or in emergencies. The ship was expected to use its steam engine almost all the time.

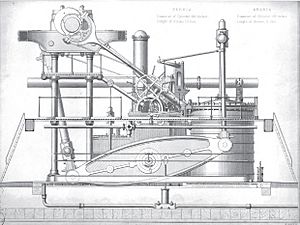

The California was powered by two large paddle wheels on its sides. Each wheel was 26 feet (7.9 m) across. These wheels were turned by a huge single-cylinder steam engine. This engine was built by the Novelty Iron Works in New York City. The engine's cylinder was about 75 inches (190 cm) wide, and its piston moved 8 feet (2.4 m). The engine turned the paddle wheels about 13 times per minute. This moved the ship at about eight knots (about 9 miles per hour or 15 km/h). It could go up to 14 knots (16 mph or 26 km/h) in good conditions. The ship carried about 520 tons of coal for fuel.

How the Engine Worked

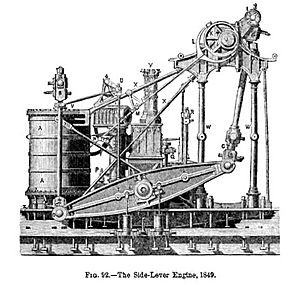

The California used a "side-lever engine." This was a strong and fairly simple type of early steam engine for ships. It was not the most efficient design, but it worked well when fuel was cheap. One problem with this engine was that it placed a lot of weight high up in the ship. This made the ship less stable in rough seas.

Like all engines, the side-lever engine needed oil to run smoothly. The steam itself would pick up a little oil before going into the cylinder. Other moving parts used oil cups. The oil used back then was a type of whale oil.

The Californias engine used steam at about 10 pounds per square inch (psi). This steam was made by two boilers that used salt water and burned coal. Steamships needed a lot of coal, from 2 to 10 tons every day. This made them expensive to run. They could travel about 3,000 miles (4,800 km) before needing more fuel. Twelve firemen worked around the clock to shovel coal into the Californias boilers.

A regular sailing ship usually traveled at 4-5 knots (about 5-6 mph or 7-9 km/h). A clipper ship averaged about 6-7 knots (7-8 mph or 11-13 km/h). Clipper ships could go much faster, up to 15-20 knots (17-23 mph or 28-37 km/h) in perfect conditions. For example, the Flying Cloud set a world record. It sailed from New York City to San Francisco around Cape Horn in just 89 days and 8 hours. This record lasted for over 130 years!

The California left New York City on October 6, 1848. It was not full, carrying only some of its 60 first-class passengers and 150 economy passengers. Only a few were going all the way to California. The ship had a crew of about 36 men. The California left New York before the news of the California Gold Rush had fully reached the East Coast.

It reached Rio de Janeiro in a record 24 days from New York. There, it stopped for engine repairs and to get more coal, fresh water, wood, and food. After sailing through the Strait of Magellan, it stopped at Valparaíso, Chile; Callao, Peru; and Paita, Peru for more supplies. The coal for these stops had been sent ahead by other sailing ships.

The Gold Rush Journey

As news of the California Gold Rush spread, the California started picking up more passengers who wanted to go to California. In Valparaíso, almost all the remaining spots on the ship were filled. When the ship arrived in Panama City on January 17, 1849, there were many more people waiting than there was room.

To decide who would get on board, a lottery was held. Tickets cost $200, and some people sold their tickets for much more money. The SS California eventually sailed for San Francisco with about 400 passengers and its crew of 36. Many more passengers were left behind, hoping to find another ship later.

On the way to San Francisco, the ship ran low on coal. It had to stop in San Diego and Monterey, California to get wood to burn in its boilers. The engines were simple enough to burn either coal or wood. Any extra wood on board was also used as fuel. The ship had more passengers than expected, and the strong southbound California Current meant it used more coal than planned. Since it was the first steamship on this route, there was no past experience to guide how much fuel was needed.

Soon after arriving in San Francisco, almost all of the crew left the ship. They had heard about the gold and wanted to try their luck. It took Captain Cleveland Forbes two months to hire a new crew and get more coal. The California left San Francisco on May 1, 1849. It carried mail, passengers, and valuable goods back to Panama. It reached Panama City on May 23, 1849. The new crew was much more expensive, but the route was so profitable that the extra costs were simply added to the ticket prices.

The mail, passengers, and important goods flowing to and from California quickly became a very good business. Much of the gold found in California was sent back East by steamship through Panama. Businesses also needed new goods, which were mostly available in the East. By the end of May 1849, 59 ships, including 17 steamers, had brought about 4,000 passengers to San Francisco.

As some early miners found gold, many bought tickets to return to the East Coast through Panama. This was the fastest and most popular way to travel. Soon, a very profitable steamship route was running regularly to and from Panama City. Most of the gold found in California was eventually sent back East this way. Gold shipments, with guards, would go to Panama. Then, they would take a well-protected mule and canoe trip across the Isthmus. Finally, they would catch another steamship to the East Coast, usually New York City.

As the Panama Railroad was being built, passengers, gold, and mail used its tracks as they were laid across Panama. These shipments helped pay for the railroad's construction. After it was finished, its 47 miles (76 km) of track became some of the most profitable in the world.

The first three steamships built for service in the Pacific were the California (1848), the SS Oregon (1848), and the SS Panama (1848). The Oregon was launched on August 5, 1848, and arrived in San Francisco on April 1, 1849. It was used regularly on the Panama City-San Francisco route until 1855. The Panama was launched on July 29, 1848, and arrived in San Francisco on June 4.

The trip from Panama City to San Francisco usually took about 17 days. The return trip from San Francisco to Panama City was slightly faster. As more steamships became available, a regular schedule was set up. Ships would travel to and from Panama City about every ten days.

As the gold rush continued, the very profitable San Francisco to Panama City route needed more and larger paddle steamers. Ten more ships were eventually added to the service. The California soon seemed small compared to these newer, bigger ships. It operated regularly between San Francisco and Panama from 1849 to 1854. In 1856, it was used as a spare ship. In 1875, its engine was removed, and it was changed into a sailing ship. It was then used to carry coal and lumber until it was wrecked near Pacasmayo Province, Peru, in 1895.

The Panama Railroad's Impact

In 1851, William H. Aspinwall and his partners started building the Panama Railroad across Panama. This railway began in a town called Aspinwall (now Colon) on the Atlantic side. The Pacific end was Panama City. Tracks were laid from both ends until they met in January 1855. Building this railroad cost about 5,000 lives and $8 million.

This railroad made the sea routes through Panama very appealing. It made travel to or from California faster and more reliable, even before it was fully completed in 1855. A trip that used to take 7-10 difficult days was changed into a one-day train ride. After 1855, a trip from the East Coast to California could reliably take about 40 days or less. The Panama route and the easy one-day train ride across Panama basically stopped other routes to California through Nicaragua and Mexico. Most miners returning home (about 20% of the "Argonauts" went back East) and their gold took the Panama route.

Ship's Journey Log

| Log of the SS California Captain Cleveland Forbes ** |

||

|---|---|---|

| Location | Date | Time |

| Left New York | *October 6, 1848 | at 6.50 P.M. |

| Near Bermuda | October 9, 1848 | |

| Crossed Equator heading south | October 24, 1848 | |

| Passed Fernando de Noronha | October 25, 1848 | |

| Arrived at Rio de Janeiro‡‡ | November 2, 1848 | at 4 P.M. |

| Left Rio de Janeiro | *November 25, 1848 | at 5 P.M. |

| Navigating Straits of Magellan | December 7–12, 1848 | |

| Arrived at Valparaíso (Chile) | December 16, 1848 | at 9 A.M. |

| Left Valparaíso | December 22, 1848 | at 5 P.M. |

| Anchored at Callao Roads | December 27, 1848 | at 10 A.M. |

| Left Callao (near Lima Peru) | January 10, 1849 | at 6.30 P.M. |

| Arrived at Paita (Peru) | *January 12, 1849 | at 9 A.M. |

| Left Paita | January 14, 1849 | at 12 noon |

| Crossed Equator heading North | January 15, 1849 | |

| Arrived Panama | *January 17, 1849 | at 12 noon |

| Left Panama City | February 1, 1849 | |

| Arrived Acapulco (Mexico) | February 9, 1849 | |

| Left Acapulco | February 11, 1849 | |

| Arrived San Blas, Nayarit (Mexico) | February 13, 1849 | |

| Left San Blas | February 14, 1849 | |

| Arrived at Mazatlán (Mexico) | February 15, 1849 | |

| Left Mazatlán (Mexico) | February 15, 1849 | |

| Arrived at San Diego (Cal.) | February 20, 1849 | |

| Arrived at Monterey (Cal.) | February 23, 1849 | at 11 A.M. |

| Left Monterey | February 27, 1849 | at 7 P.M. |

| Arrived at San Francisco | February 28, 1849 | at 10 A.M. |

The logbook of the SS California was first printed in a newspaper called the New Orleans Daily Picayune. All the dates in the log are given in "sea time." Navigators start their day at noon. This is because they usually figure out their latitude by looking at the sun at that time. They also figure out longitude during the day using a special clock called a marine chronometer. The navigator's day is one day ahead of the regular calendar day.

‡‡ The trip from New York City to Rio de Janeiro took 24 days, which was a new record! The long stop in Rio was because the engine needed repairs, and the Captain was sick.

The End of the California

The SS California was wrecked and sank in the Pacific Ocean near Pacasmayo Province, Peru, in 1895. Luckily, no lives were lost. At that time, the ship had been changed into a sailing ship called a barque. It was being used to carry coal and lumber. On its last trip, it had left Port Hadlock in Washington state with a cargo of lumber worth $3,000.