John Mullan (road builder) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Mullan Jr.

|

|

|---|---|

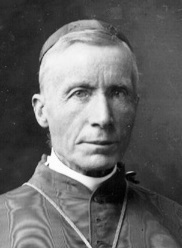

John Mullan in the 1870s or 1880s

|

|

| Born | July 31, 1830 Norfolk, Virginia, U.S.

|

| Died | December 28, 1909 (aged 79) Washington, D.C., U.S.

|

| Occupation | Soldier, civil servant, lawyer |

| Years active | 1852 to 1884 |

| Known for | Building the Mullan Road in Montana, Idaho, and Washington state |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1852–1863 |

| Rank | |

John Mullan Jr. (born July 31, 1830 – died December 28, 1909) was an American soldier, explorer, and road builder. After finishing his studies at the United States Military Academy in 1852, he joined a survey team. This team explored western Montana and parts of southeastern Idaho.

Mullan discovered Mullan Pass and helped build the famous Mullan Road. This important road connected Montana, Idaho, and Washington state. He worked on it from 1859 to 1860. Later, he became a successful real estate dealer and lawyer in California. He also worked as an agent for several states, helping them get money from the government.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Mullan Jr. was born in Norfolk, Virginia, on July 31, 1830. His parents were John and Mary Mullan. He was the oldest of 11 children. In 1833, his family moved to Annapolis, Maryland. His father was a sergeant in the United States Army.

John Jr. started school in 1839. Even though his family had many children, they managed to pay for his education. He went to St. John's College in Annapolis. There, he studied many subjects like Greek, Latin, history, and mathematics. He also learned about surveying and geology. Mullan graduated from St. John's in 1847 when he was just 16 years old.

In 1845, the Army post at Fort Severn in Annapolis became the United States Naval Academy. John Mullan Sr. was assigned to work for the Navy there. He spent the rest of his career doing repairs and cleaning at the Naval Academy.

West Point Training

John Mullan Jr. wanted to join the Army like his father. He applied to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. The Mullan family had good political connections. Many respected people in Annapolis wrote letters recommending John Jr. Even the Maryland state politicians asked President James K. Polk to accept him.

In 1848, Mullan visited President Polk in Washington, D.C. Polk reportedly asked if Mullan was "rather small to want to be a soldier." Mullan bravely replied, "I may be somewhat small, sir, but can't a small man be a soldier as well as a tall one?" Polk was impressed and gave him a spot at West Point six weeks later.

Mullan started at West Point on July 1, 1848. West Point was known as the best engineering school in the country. Mullan studied engineering, math, and science. He learned how to use a compass and odometer for navigation. Mullan loved to read about the newly acquired western United States. He graduated in 1852, ranking 15th in his class of 43. Many of his classmates became famous generals, like George B. McClellan.

After graduating, Mullan became a brevet 2nd Lieutenant in the Army. He was first sent to Fort Columbus in New York Harbor. In November 1852, he traveled by steamship to San Francisco. He was then assigned to the 1st Artillery Regiment.

The Stevens Survey Expedition

Getting Ready for the Journey

In 1853, President Franklin Pierce chose Isaac Stevens to be the Governor of the new Washington Territory. Stevens also got a big job: leading a survey to find railroad routes across the Pacific Northwest. The government wanted to find the best way to build a railroad to the West Coast. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis was eager for these surveys to happen.

The Stevens survey was a very important project. It was the first big exploration of the western United States since the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806). Stevens chose many different people for his team. There were soldiers, laborers, mapmakers, engineers, and scientists. Mullan joined the team as a topographical engineer. This meant he would help map the land.

Mullan traveled east to St. Louis, Missouri, a busy city. In May, he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant. He then met with Stevens and other leaders of the survey. Stevens told Mullan to go to Fort Union. This fort was where the Missouri River and Yellowstone River meet. Mullan's job was to set up a supply base there.

From Fort Union to Fort Benton

Mullan and his group traveled by steamboat up the Missouri River. They left St. Louis on May 21 and arrived at Fort Union on July 3. During the trip, Mullan recorded weather observations. He also helped map the land the ship passed through. On this journey, Mullan met Native Americans for the first time.

While at Fort Union, Mullan explored the nearby area with 11 other men. They traveled along Big Muddy Creek and the White Earth River. They mapped the land before returning to Fort Union.

Stevens and the main survey party arrived at Fort Union on August 1. On August 9, the whole team left the fort. They traveled along the Milk River. Mullan continued to make maps and record weather data. The group reached Fort Benton on September 1. This was the highest point on the Missouri River where boats could travel.

Peace Mission to the Salish People

On September 9, Stevens sent Mullan on an important mission. Mullan was to meet with the Salish nation. He needed to tell them that the United States government wanted peace. He also asked them to make peace with the Piegan Blackfeet tribe. Mullan also hoped to get guides from the Salish. These guides would help him explore mountain passes in the Rocky Mountains.

Mullan traveled south from Fort Benton. He crossed several rivers and passed through the Judith Gap. On September 18, he found about 50 Salish lodges and 100 Kalispel lodges. The tribes welcomed him warmly. Mullan, who had studied French, was able to talk with some Salish who spoke French. The Salish chief agreed to consider the peace message. He also sent four men with Mullan to guide him through the mountains.

Mullan and his guides returned to the Musselshell River. They then followed the Smith River through the Castle Mountains. They reached the Missouri River. The Salish guides led him across the Helena Valley. On September 24, he crossed the Continental Divide through a pass. He then went down into the valley of the Little Blackfoot River. He followed the river to the Missoula Valley. Then he traveled south through the Bitterroot Valley. He reached Fort Owen on September 30, 1853. There, he met up with the main Stevens survey party.

Exploring the Bitterroot Valley

On October 6, 1853, Mullan joined Stevens at the mouth of Hellgate Canyon. The railroad survey was behind schedule. Stevens needed to go to Olympia to start his job as Territorial Governor. He gave Mullan the important task of mapping western Montana. Mullan's goal was to find the best route for a railroad. He also had to record weather, river flows, and information about wildlife and geology.

On October 8, Mullan set up a camp called Cantonment Stevens. It was near Corvallis, Montana. He and 15 men built barns, a corral, and log cabins. Mullan then tried to explore the southern Bitterroot Valley. He wanted to find a way to Fort Hall in Idaho. But his guide got lost, and they had to return to camp.

In November, Mullan explored the Bitterroot River to its source. He crossed the Sapphire Mountains and Anaconda Range. He also explored the Big Hole River. He traveled through heavy snow and strong winds. Rivers were covered in thin ice, and horses often fell through. His team often went hungry. In 45 days, he traveled over 700 miles. He crossed the Continental Divide four times in winter. He found two wagon routes from Fort Hall to Fort Owen.

Finding Mullan Pass

In February 1854, Mullan learned about a better mountain pass from Native Americans. On March 2, he left the Missoula Valley with five men, including Gustav Sohon. He traveled along the Little Blackfoot River and over "Hell Gate Pass." He then followed the Missouri River north to Fort Benton, arriving on March 12.

Mullan got soldiers, wagons, and supplies. He left on March 14 to find a good road from Fort Benton. He followed the Missouri River, which was flat. Then he went inland and found a wide, flat prairie. This allowed him to avoid rugged mountains. He followed Little Prickly Pear Creek back to the Missouri River. On March 21, he camped near the Lewis and Clark Range. Following Tenmile Creek, he discovered and crossed Mullan Pass.

After crossing Mullan Pass, he reached the Little Blackfoot River valley. He arrived back in the Missoula Valley on March 28. Mullan Pass was longer than other routes. But it had a gentle slope and was not heavily wooded. This made it perfect for building a wagon road. Mullan had crossed it in winter with no problems. The importance of Mullan Pass was quickly recognized.

Exploring the Flathead Valley

Mullan then looked for a route west from the Flathead Valley to eastern Washington. On April 14, Mullan left Cantonment Stevens with four men. He followed the Clark Fork River to where it meets the Flathead River. His group built rafts to cross the Flathead River. They reached Camas Prairie on April 17. They spent the night with the Kalispel Indians.

They traveled north for two days and met a group of Yakama people. They followed the Flathead River to Flathead Lake. Mullan's group traveled north of the lake but could not find a way west. They turned south again on April 27.

The party built a bridge to cross the Tobacco River. A Ktunaxa (Kootenai) Indian offered them hospitality. They followed the Tobacco River to its source near Fortine, Montana. The next day, they met Michael Ogden, a trader. After resting, they continued south back to Cantonment Stevens. They found a series of hot springs near Hot Springs, Montana.

On May 4, Mullan's group was blocked by the swollen Clark Fork River. They built two rafts. One raft, with Mullan and others, was swept downstream. Mullan was almost drowned when the raft hit a snag. His men saved him. They swam to a rocky island and pulled the raft close. They saved most of their supplies before the raft broke apart. After this dangerous event, Mullan's group arrived back at Cantonment Stevens on May 5.

Final Explorations

Mullan still needed to find the best route for a railroad or wagon road. On May 21, Mullan set out on horseback. He followed the Clark Fork River to Lake Pend Oreille. The group then canoed across the lake and down the Pend Oreille River. They reached the St. Ignatius Mission near Cusick, Washington. Mullan then traveled to Fort Colville, a trading post on the Columbia River. After getting supplies, he returned to St. Ignatius.

Mullan's group then went south to the Spokane Valley. They returned east by following the Coeur d'Alene River into the mountains. They crossed Lookout Pass back to the Bitterroot Valley and Cantonment Stevens. Mullan reported that the Pend Oreille route was not as good as the Lookout Pass route because of flooding.

Mullan then explored the last route: Lolo Pass, following the Lewis and Clark Expedition trail. Mullan and his group left on September 19. They followed Lolo Creek and then the Lochsa River. The route over Lolo Pass was steep and blocked by many fallen trees. After 11 days of very difficult travel, Mullan's group reached the Weippe Prairie. They continued following the Clearwater River.

About 20 miles from the Snake River, Mullan's group went south up Lapwai Creek. They found the farm of fur trader William Craig. Craig and the local Niimíipu (Nez Perce) people gave them fresh vegetables. This was the first fresh food the group had eaten in 21 months. Mullan's party stayed at the Craig farm. Then they traveled west to Fort Walla Walla. They reached Fort Walla Walla on October 9. Mullan advised that the future military road should use Lookout Pass. He was then released from the Stevens survey team.

Between Expeditions (1855-1858)

In December 1854, Mullan went to Olympia. He helped Stevens write reports about the survey mission. Mullan and Stevens became good friends. Stevens sent Mullan to Washington, D.C., with ideas to build a military road. In January 1855, Mullan learned that Congress had set aside $30,000 for a military wagon road. But Secretary of War Davis refused to spend the money. He felt it was not enough to build the road properly.

Mullan tried to convince Davis to release the money, but he was not successful. On February 28, the Army promoted Mullan to 1st Lieutenant. He was ordered to join his unit in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. This area was suffering from a yellow fever outbreak. Mullan did not report immediately, but he eventually joined his unit in July. He asked to transfer to the Corps of Topographical Engineers, but his request was denied.

Seminole War Service

Many historical sources say that Mullan fought in the Third Seminole War in Florida. This war started in November 1855. Some sources claim he spent up to two years fighting there.

However, Mullan's biographer, Keith Peterson, believes Mullan spent little to no time in Florida. Mullan stayed in Louisiana until January 1856. He was then ordered to Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland. He arrived there in March. He was away from his unit in May and June 1856, but this would have left almost no time to travel to Florida and fight. He returned to his unit in July 1856. He stayed there until December 1857, when he was sent to Washington, D.C., to work with Isaac Stevens again.

Approval for the Mullan Road

Isaac Stevens believed that a military road was needed to move troops and supplies. He also thought it would help with settlement and prevent Native American attacks. Stevens resigned as Washington Territory's governor in July 1857. He was then elected as its representative in Congress. Stevens moved to Washington, D.C., and began pushing for money to build the Fort Benton-Fort Walla Walla road.

In late 1857, Mullan was ordered to Washington, D.C., to help Stevens. Moving military personnel and supplies was very important due to ongoing conflicts. On March 15, 1858, the War Department ordered the construction of the Fort Benton-Fort Walla Walla Road. Mullan was put in charge of this project.

The Coeur d'Alene War

Mullan thought he could finish the military road by December 1858. He left New York City on April 5 and arrived in San Francisco on May 1. He then traveled to Fort Dalles, arriving on May 15. Mullan hired 30 civilians for his road crew. He began working on the road. They had graded the flat prairie when news arrived. On May 17, 1858, Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Edward Steptoe had been defeated. He was routed by warriors from the Cayuse, Schitsu'umsh, Spokan, and Yakama tribes. This happened at the Battle of Pine Creek. The Schitsu'umsh were angry because miners and settlers were entering their lands. They saw the Mullan Road as a threat to their territory.

This was the start of the Coeur d'Alene War.

Mullan realized he could not continue building the road during the conflict. On May 27, he asked Steptoe for 65 soldiers to protect his crew. Steptoe replied on May 30 that he could not send soldiers. Mullan had to stop his road-building work. He kept only a few men to care for the horses and mules.

Looking for the Enemy

Mullan immediately volunteered to serve under Colonel George Wright. Wright was leading the Army's response. Wright was ordered to punish the tribes severely. He was also told that any surrender must allow Mullan to build his road without trouble. Mullan knew no road work could be done in 1858. He wrote to the War Department asking for more money for the road.

On July 14, Mullan left for Fort Walla Walla. Wright signed a treaty with a group of Niimíipu (Nez Perce) on August 6. They agreed to fight with the U.S. Army. On August 7, Captain Erasmus D. Keyes led 700 men out of Fort Walla Walla. This group included 200 civilian workers and 30 Niimíipu soldiers. They also had cannons.

The column reached its destination on August 10. They began building Fort Taylor. Mullan was ordered to clear a path along the river. On August 11, Mullan's men captured two Native Americans. One escaped into the Snake River. Mullan chased him, firing his pistol. The other man fought Mullan, almost drowning him. Mullan survived because the man stumbled into a hole. The Native American then escaped.

Wright's column crossed the Snake River on August 25 and 26. On August 30, a small group of Native Americans fired on Wright's camp. Mullan and his Niimíipu chased them but were called back. The next day, Mullan and his scouts got separated from the main group. They had to work hard to avoid being seen by enemy patrols before rejoining Wright.

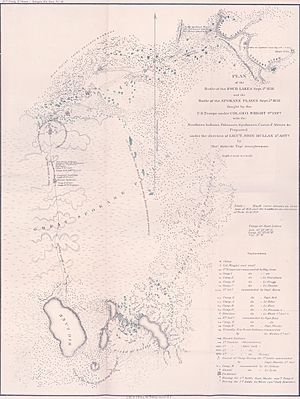

Battles of Four Lakes and Spokane Plains

On September 1, 1858, Mullan fought in the Battle of Four Lakes near Spokane, Washington. At the start of the battle, he led his Niimíipu scouts in an attack on the Native American left side. They drove the enemy from a ridge. Wright praised Mullan greatly for his actions.

Wright rested his men for three days. On September 5, they moved north again. The Native Americans had gathered more warriors. Between 500 and 700 warriors began attacking the column. They set fire to the prairie and used the smoke for cover. Wright moved his group toward the Spokane River. He ordered Mullan and his 30 Niimíipu scouts to go ahead. They raced through the smoke to find the right direction for the column. They did this many times for eight hours. Wright's cavalry charged into the enemy, scattering them. By nightfall, the column reached the river, and the Native Americans had fled. Only one soldier was slightly hurt.

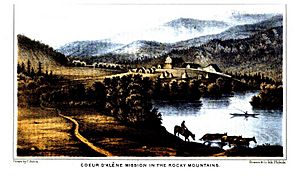

The column reached the Coeur d'Alene Mission on September 15. The Schitsu'umsh chiefs signed a surrender document on September 17. The Spokan followed on September 27. On September 23, Mullan joined a unit to find the bodies of soldiers who died at the Battle of Pine Creek.

Mullan had asked to go to Washington, D.C., to get more money for the military road. On September 30, Mullan received orders to go to Fort Vancouver. He was to wait for instructions there. Mullan left Wright's party on October 2 and arrived in Vancouver on October 9.

Building the Mullan Road

Getting More Money

Instead of waiting at Fort Vancouver, Mullan quickly left for the East Coast. He took a steamer to Panama, crossed the land, and took another steamer to New York City. He then traveled by train to Annapolis. Mullan avoided trouble because Isaac Stevens was also in Washington, D.C. Stevens needed Mullan to help get more money for the road. Secretary of War John B. Floyd also agreed that more funds were needed.

Mullan went to Washington, D.C., in December 1858. Congress was discussing the Army's budget. In late 1858 or early 1859, Jefferson Davis suggested adding $350,000 for a military road. Secretary of War Floyd supported this idea. On February 26, 1859, Davis proposed $100,000 for the road, and it was approved. In the House, Isaac Stevens also pushed for the funding. On March 1, the House approved $100,000. President James Buchanan signed the bill into law on March 3.

Mullan spent March gathering information on road-building. He ordered equipment and hired a larger civilian work crew. He also asked the military for an escort and funds for gifts for Native Americans.

Before leaving for the West Coast, Mullan got engaged to Rebecca Williamson of Baltimore. She came from a wealthy and well-connected family. They likely met in 1856 when Mullan was stationed at Fort McHenry.

Building the Road: 1859

Mullan left Baltimore on March 31 and New York City on April 5. He traveled by steamers and crossed Panama again. He reached Fort Dalles on May 15, 1859. He hired over 80 civilians for his road crew. This included his brothers, Louis and Charles, and his future brother-in-law, David Williamson. The crew had carpenters, cooks, and teamsters. The Army provided an escort of 100 soldiers. Mullan also got 180 oxen and many cattle, horses, and mules. He hired John Creighton, a famous wagon master.

Mullan's team started scouting the route on May 16. The work crew began building the road on July 1. The road went north to Fort Taylor. There, they crossed the Snake River using pontoon boats. After crossing, the crew started placing wooden mile markers. These markers often had information about distances to water. An old branding iron with "M" and "R" was used. Mullan meant "Military Road," but the crew started calling it "Mullan Road." The crew also made important maps of the area.

In mid-July, the crew reached Lake Coeur d'Alene. Mullan decided to build the road along the southern edge of the lake. This meant a steep, 700-foot descent into the St. Joe River Valley. It was very difficult to pass through the thick forest. Huge fallen trees blocked the way, and large rocks had to be blasted or moved. It took eight days just to reach the valley floor. Mullan then found a large swamp. His crew built a corduroy road across it. They reached the 240-foot-wide St. Joe River. They built two flat-bottomed boats to use as a ferry. The work crew reached the Coeur d'Alene Mission on August 16. They had built 198.5 miles of road.

Mullan's men rested at Coeur d'Alene Mission. Mullan sent Gustav Sohon ahead to find a path into the Bitterroot Mountains. While waiting, one of Mullan's men found gold. Mullan kept the discovery a secret and told the War Department. Sohon found St. Regis Pass, which Mullan named "Sohon Pass." As they moved toward the pass, Mullan found the forest incredibly thick. To speed up the work, he sent 23 men ahead. His two crews then worked toward each other.

Following the Coeur d'Alene River into the mountains, Mullan's crew had to build 50 to 60 bridges. It rained throughout October. On November 3, 15 to 18 inches of snow fell. Snow fell for a week, and then the temperature dropped below 0°F. Food supplies ran low, and winter clothing was delayed. Mullan's crew had cut about 80 miles of road through the forest and mountains. They stopped near De Borgia, Montana, and built huts and a storehouse. This camp was called Cantonment Jordan. Most of Mullan's animals died. The men had to butcher the few cattle that survived. A few men tried to take the remaining horses and mules to the Bitterroot Valley, but none survived the 100-mile trek.

The winter was incredibly harsh. On December 5, the temperature dropped below -40°F. The snow was 5 feet deep in December and 7 feet deep in January. Many men suffered from frostbitten feet. Despite the difficulties, Mullan kept his men working. About 25 soldiers got scurvy from eating too much salted meat. Mullan had vegetables brought from the Coeur d'Alene Mission. He convinced the soldiers to eat them, and the scurvy ended.

Building the Road: 1860

To stay in touch with the outside world, Mullan paid two men to carry mail to and from Fort Walla Walla. Mail arrived twice a month. Another man was sent to Salt Lake City, Utah Territory, to buy new mules. P.M. Engle was sent to Fort Benton to buy cattle and supplies. In early January, Mullan sent engineer Walter Whipple Johnson to Washington, D.C. Johnson's job was to stop rumors that the road crew was in trouble. During the winter, Mullan also decided to change his route. He realized the road should have followed the north shore of Lake Coeur d'Alene and the Clark Fork River.

In Washington, D.C., there was a fight to get more money for the Mullan Road. On December 1, 1859, Secretary of War Floyd told Congress about "great mineral wealth" in the mountains. On January 18, 1860, Senator Joseph Lane announced he would propose a bill to finish the road. Captain Andrew A. Humphreys at the War Department decided to cancel the road in April 1860. He said Mullan had spent too much money. Johnson arrived in Washington just as the money seemed lost. He and Isaac Stevens pushed for the bill to pass. Floyd also supported them, believing there was gold in the Rocky Mountains. The bill, which provided $100,000 to finish the road, passed the House on May 12. The Senate approved it on May 23. President Buchanan signed it into law on May 25.

Walter Johnson also had another mission. He convinced Floyd to order soldiers to use the Mullan Road. This would prove the road's value for military use. Johnson returned with good news about the new money.

Mullan was determined to keep building the road. On February 20, he sent his civilian workers ahead. They went to where the Clark Fork and Blackfoot rivers meet near Missoula, Montana. They were to build a large flatboat ferry and small pirogues. Mullan ordered the soldiers to start building the road from Cantonment Jordan to the Blackfoot River. By June 4, the 85-mile road was cut through to the Blackfoot. Cantonment Jordan was then abandoned.

Mullan left Lieutenant White in charge on February 26. He rode to Fort Owen, which had grown much larger. He rested for two weeks. Then he met with the Kalispel people. His good relationship with them convinced 17 Kalispel to take 120 horses. They went with Gustav Sohon across the mountains to Fort Benton. They returned a month later with supplies.

Mullan was running out of time. Major George A.H. Blake was coming up the Missouri River with 300 men. He planned to use the Mullan Road to travel to Fort Walla Walla. The road had to be finished by the time he arrived. This meant Mullan had to work faster and cut corners. Floods destroyed his ferries twice. Mullan had to build many bridges across the Blackfoot River. The construction crews reached Mullan Pass on July 18, 1860. The treeless top of the pass meant the hardest part of the road-building was over. The only remaining difficulty was at Tower Rock. The crew spent four days digging and blasting there.

The construction crew reached the Sun River on July 28. This meant the main grading work was done. For the last 55 miles, the crew only had to place mile markers. Mullan finished the Mullan Road on August 1, 1860. He immediately wrote to Captain Humphreys. He told him that the southern route around Lake Pend Oreille was wrong. He asked for money and permission to reroute the road around the north end. He then sent Theodore Kolekci with all his field notes to the Army in Washington, D.C.

The Mullan Road cut through 120 miles of thick forest and 424 miles of prairie. About 30 miles of hillside cuts were dug. Hundreds of bridges and several ferries were built. Building the Mullan Road, along with his other explorations, made John Mullan famous. He became known as a great explorer of the Inland Northwest. In January 1861, the Washington Territorial Legislature thanked Mullan for building the road.

Later Military Years

On August 5, 1860, Mullan returned west to Fort Walla Walla. He made repairs to the Mullan Road as he went. Major Blake and his men followed behind him. Mullan reached the Coeur d'Alene Mission around September 21. He arrived at Fort Walla Walla on October 8. Mullan found orders waiting for him. He was told to stay at the fort for the winter and write a report. Mullan stayed until January 1861. Then he and Gustav Sohon traveled to Fort Vancouver. They took a steamer to San Francisco. From there, they traveled by Butterfield Overland Mail (a stagecoach) overland to St. Louis. The stage trip took 22 days.

Rerouting the Mullan Road

The American Civil War was about to begin. There was little desire in the Army to spend money on a road in the Washington Territory. Mullan bravely suggested building a military road from Fort Laramie in Wyoming to Fort Walla Walla. This idea was quickly turned down. Mullan had asked to reroute the Mullan Road in August 1861, and Captain Humphreys had approved this plan on February 7. Mullan stayed in Washington for about six weeks. He met with Isaac Stevens. Mullan left the city in early March and reached San Francisco on April 5.

It is not clear exactly when Mullan reached Fort Walla Walla. The Corps of Topographical Engineers had approved 15 months of work with a budget of $85,000.

Mullan was delayed in starting work. The Fort Colville Gold Rush and the Clearwater Gold Rush made it hard to find men and animals. Mullan had planned to start work on April 1, but his late arrival prevented that. He finally left Fort Walla Walla on May 13. Mullan set out with 60 civilian workers and 21 soldiers as guards. Another 39 soldiers guarded the supply train. Due to the risk of Indian attacks, 79 more soldiers followed a few days later.

Mullan reached the Snake River on May 20. By June 4, the crew had repaired about 156 miles of road. They reached Antoine Plante's farm and ferry on the Spokane River. Mullan's civilians and soldiers began cutting through thick timber north of Lake Coeur d'Alene on June 5. They built two supply depots as they worked east into the Rocky Mountains. They reached the top of the pass (Fourth of July Summit) on July 4. They had cut 6.5 miles through the thick forest. They added another 5.5 miles by July 14. The party reached the Coeur d'Alene Mission on July 31, a month behind schedule.

Mullan then learned that the steamer Chippewa had been destroyed by fire and explosion. This steamer was carrying Mullan's supplies. Mullan had to send riders back to Fort Walla Walla to buy expensive new supplies. On August 11, 1862, while Mullan was slowly cutting through the Bitterroot Mountains, the War Department promoted him to Captain. On August 13, Mullan sent Lieutenant Marsh with 50 soldiers and civilians. Their job was to lightly repair the road ahead. This would allow supplies to be moved into the Bitterroot Valley for the winter camp. Three days later, the party reached the 222-mile marker on the Mullan Road.

Snow began falling on November 1. Mullan ordered Lieutenant Marsh to take the supply train to the Clark Fork and Blackfoot rivers. He was to set up another supply depot there. A messenger reached Mullan on November 4, ordering the troops to return east. But with heavy snow, Lieutenant Marsh knew travel was too risky. The work crew reached the depot on November 22. Mullan set up five work-camps along the Clark Fork. Each camp was where a lot of digging was needed to avoid crossing the river too much. The depot and camps were called Cantonment Wright. The animals were driven south to the Bitterroot Valley, hoping for warmer temperatures. By December 1, daytime temperatures were below 0°F. This was one of the worst winters ever recorded. Most of Mullan's animals died from cold and hunger. The men had to pull supplies from the depot using sledges. The cold was so bad in mid-January that all work stopped for two weeks. Mullan spent Christmas Day at John Owen's cabin. He gave the first public lecture in Montana state history there. During the winter, Mullan's men built a four-span bridge across the Blackfoot River. They also dug and blasted almost seven miles of cut-outs along the Clark Fork.

The winter was so harsh that Mullan's party could not move again until May 23, 1862. With little repair work left, the crew reached Fort Benton on June 8. Mullan returned to Fort Walla Walla on August 13. By this time, people in the Washington Territory were discussing new laws. They were preparing for statehood. Some wanted the new territory to include Washington state, the Idaho panhandle, and western Montana. They wanted the capital moved to Walla Walla. Mullan met with Walla Walla's leaders. He became convinced that this was the best option. Mullan disbanded his work crew and sold his remaining animals. He left for Washington, D.C., in early September.

Mullan took Gustav Sohon with him. In October 1862, they made the difficult stagecoach journey from San Francisco to St. Louis again. Mullan found working at the Topographical Engineers difficult. He wanted to work from home, but he had to work in an office. He hired staff without permission. He tried to include extra material in his report. He also started asking for new money to rebuild part of the Mullan Road. The department told him to finish his report quickly.

Territory Politics

Representative James Mitchell Ashley was in charge of the House Committee on Territories. He liked states with square borders. Ashley asked Mullan for his advice on how to reorganize the Washington Territory. In mid-December 1862, Mullan drew a map for a new territory. It included present-day Washington state, the Idaho panhandle, and western Montana. He also proposed another new territory called "Montana." This territory would include southern Idaho and eastern Montana.

Ashley introduced a bill on December 22, 1862, to create the new Montana Territory. It passed the House easily on January 12, 1863. Mullan spent a lot of time in 1863 trying to get the Senate to pass Ashley's bill. Mullan also wanted to be named governor of the new "Montana Territory." He asked many important people for their support. But William H. Wallace, Washington Territory's representative, wanted much smaller territories. To stop Ashley's bill, Wallace introduced his own bill in the Senate.

By March 3, 1863, the last day of the session, both bills were stuck. Wallace then pushed the Senate to pass a new bill. This bill changed Washington Territory's borders to his preferred ones. It also created the new Idaho Territory from the rest of the land. Ashley was very angry. He demanded a committee to fix the differences between the bills. But it was almost midnight, and Congress members were tired. At 2:00 AM on March 4, the House passed Wallace's bill. President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill into law near dawn.

Mullan was worried by Wallace's actions. He immediately tried to become Idaho Territory's governor. He gave his letters of recommendation to Lincoln on the morning of March 4. Three of Mullan's Senate supporters met with the president on March 5 to support him. But Wallace was a friend of Lincoln's. He had also been asking for the position. Mullan was a Democrat, and Wallace was a Republican. Lincoln nominated Wallace as the first Territorial Governor of Idaho Territory. The Senate approved the nomination on March 10.

Leaving the Army

Mullan had planned to use his Army connections to make money. He had bought property and businesses in Walla Walla. He wanted to return there and use his Army experience to become rich.

On April 4, 1863, John Mullan resigned from the U.S. Army. Losing the governorship of Idaho Territory made Mullan bitter. But it was not the only reason he left the Army. He disliked Army rules. He was eager to make money for himself and his family. He already had business interests in Walla Walla.

Mullan married Rebecca Williamson on April 28, 1863.

Business Ventures

Walla Walla Railroad

In 1862, Mullan began planning his business career after the Army. In 1861, his younger brother, Louis, agreed to help start a railroad company. This railroad would be 30 miles long. It would go from Walla Walla west to Wallula. This would bypass rapids on the Columbia River. The territorial legislature approved the railroad's plan in January 1862. Louis likely told John about the railroad. In October, John sent a letter to the company's founders. In the letter, read at a public meeting in Walla Walla, John Mullan said the company could raise $250,000 to $300,000. The founders were very excited.

On January 1, 1863, John Mullan announced the railroad project to industry journals. He asked for investors. The company's rules were approved on March 14, 1863. On March 28, 1863, Mullan agreed to be a leader of the new railroad.

After his marriage, John and Rebecca Mullan traveled to New York City. Mullan gave a long speech about eastern Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana. He spoke to the American Geographical and Statistical Society on May 9. While in the city, Mullan met with some of the railroad company's founders.

The state charter required the railroad route to be surveyed by November 1, 1863. The road had to be open by November 1, 1868. However, the railroad project never went forward. Steamship companies put new, fast ships on the Columbia River in spring 1863. These ships made freight prices so low that the railroad could not compete.

Walla Walla Farm

Mullan bought several businesses near Fort Walla Walla in spring 1858. He expected the area to become a boom town after his road was finished. He bought part of a sawmill and a 480-acre farm. He also fully owned a livery stable. Mullan sent his 20-year-old brother Louis to run the businesses. He gave Louis the legal power to act for him. Mullan's partner sold his shares to Mullan in 1860. By then, Louis was not handling the businesses well. So, Mullan sent his 24-year-old brother Charles to help Louis. Charles was also not very capable.

John and Rebecca arrived in Walla Walla in August 1863. Mullan found that Louis and Charles had been sued often for not paying bills. The farm, sawmill, and stable were almost bankrupt. He also found that Louis and Charles were using his name to get expenses. Louis had also fenced off 160 acres of John's farm and claimed it as his own. In September, Mullan's 30-year-old brother, Dr. James A. Mullan, and his 17-year-old brother, Ferdinand, arrived. James immediately started working with Louis to cheat John. The relationship between John and Louis broke down. On December 27, 1863, John tried to evict Louis. Louis sued, claiming he owned the 160 acres. He said John and Charles were trying to sell property without his consent. In court, James and Ferdinand claimed John had promised all brothers an equal share in the farm and businesses.

By late 1864, John Mullan was bankrupt. He sent Rebecca to Baltimore. He stayed in Walla Walla for a few months to sell his belongings and pay some debts. Then he also returned to Baltimore. Louis gave James a share in the 160-acre farm. They sold it after a few years.

Chico Stagecoach Business

Mullan realized that guidebooks about the West sold well. He decided to turn his 1863 Army report into a book. He worked on the book throughout 1865. He published the Miners and Traveler's Guide in the middle of that year.

While working on his book, Mullan learned about a plan. John Bidwell, a large landowner in northern California, and miner Elias D. Pierce wanted to start a passenger and freight stagecoach line. It would go between Bidwell's ranch (near Chico) and the booming mining town of Boise. Mullan decided to join this venture. He traveled alone to Boise, arriving in mid-1865. Mullan spent about two months helping to improve an existing road.

In August 1865, Mullan led the first group to travel along the newly improved road. They arrived in Ruby City (southwest of Boise) on September 1. But the new Idaho and California Stage Line did not have enough coaches for regular service. Also, Native Americans strongly opposed the new road.

In October 1865, Mullan returned east to raise money for the stage line. He lived with his wife's family in Baltimore. He tried to get a mail contract with the U.S. Post Office Department. He thought his brother-in-law, L.T. Williamson, would have a better chance of winning the contract. On March 18, 1866, the Post Office gave the contract to Williamson. Mullan then started a company called the California and Idaho Stage and Fast Freight Company. He raised $300,000 in New York and Baltimore to fund the new stage line.

Mullan returned to San Francisco in May 1866. He hired 100 to 200 Chinese immigrants to repair the road and build stations. He also built a blacksmith shop in Chico. He bought coaches and animals. The first stagecoach left just after midnight on July 1. It reached Ruby City three days later.

However, the California and Idaho Stage and Fast Freight Company soon failed. Native Americans, angry about new white settlers, burned several stations. They also killed many horses. Mullan convinced the U.S. Army to place troops along the line, but there were not enough. Competition from other roads also hurt Mullan's business. A new road between Umatilla, Oregon, and Boise brought a lot of freight. Another new road opened in September 1866 between Boise and Hunter, Nevada. Mullan had also upset several wealthy businessmen while trying to get the mail contract. These businessmen refused to help Mullan. He ended up $12,000 in debt. Mullan's last stagecoach left on November 18, 1866.

California Land Attorney

After his stagecoach business failed, John Mullan moved to San Francisco. Rebecca joined him there. John found a job in a local bank. Rebecca also worked at the bank as a copyist. Together, they earned $200 to $300 a month. Mullan also worked for the Surveyor General of the United States in 1867. Mullan had read a lot about law over the years. He decided to become a lawyer. After a few months of study, he passed the California bar exam.

Mullan's first big client was the City of San Francisco. They hired him as an engineer and lawyer. He helped plan an expansion of the city's fresh water system. Mullan earned $8,000 for this work.

In 1868, Mullan became the manager for the California Immigration Association. He helped settlers get information about public land. He opened a real estate office in 1871. By 1872, he had a law practice in the same office.

In 1873, Mullan started a law firm, Mullan & Hyde, with Frederick A. Hyde. Their partnership lasted until 1884. The firm became the largest land speculator in California. When territories become states, the federal government gives large amounts of federal land to the state. This land is supposed to be sold to the public. The money from sales is meant to support education and the new state government.

However, the California State Land Office was weak. Mullan & Hyde worked with clerks in the land office to illegally obtain land. Mullan and his staff could view and even remove official documents. They bribed people to file false land claims. They sold illegally obtained land at very high prices. They also bought land without making the required down payment.

Mullan & Hyde also used a system called "in lieu" to get land. Sometimes, people who bought public land found out it was already owned by someone else. In these cases, they could choose other public land "in lieu" (instead) of the land they lost. Mullan & Hyde would get "in lieu" forms. They would copy the information, put a fake name on the form, and backdate it. Then they would slip the fake form into the state and federal land office files. This meant that even "in lieu" land was often already taken. Mullan & Hyde became the top firm for stealing "in lieu" land.

Mullan also made money from selling "scrip land." Under the Morrill Act of 1862, the federal government gave each state land to support state colleges and universities. The University of California was supposed to keep this land as an investment. But the state gave the university so little money that it started selling this land at low prices. Mullan worked with public land officials. He bought large areas of scrip land before it was available to the public. Then he resold the land at much higher prices.

His unethical land dealings made Mullan a rich man. He was able to pay off the debts from his stagecoach business. Mullan was lucky. In February 1904, the federal government charged Frederick A. Hyde with fraud. Hyde was accused of widespread fraud. His trial lasted four years. Hyde was found guilty in June 1908. He was sentenced to two years in prison and fined $10,000. He appealed, but the Supreme Court upheld his sentence in 1912. Mullan was not charged, but his reputation was damaged for the rest of his life.

State Agent in Washington, D.C.

In 1878, Mullan offered to help California Governor William Irwin. He would try to get money from the federal government for a problem in the California Statehood Act. When new states join the U.S., the federal government usually gives them 5 percent of the money from selling federal land in that state. California's statehood act, passed in 1850, did not include this rule. Mullan offered to represent California in Washington, D.C., to get these missing funds. In return, the state would pay Mullan 20 percent of the money he collected. The state legislature approved this. Governor Irwin appointed Mullan on November 1, 1878. By 1881, Nevada and Oregon also hired Mullan as their agent. The Washington Territory did so in 1886.

Mullan did not just work on land claims. He acted as an agent for each state on many issues. This included getting money back for state spending during Indian wars. He also helped with federal payments to Civil War soldiers. Over time, he became a lawyer-ambassador. He wrote requests for Congress and lobbied federal officials. Mullan won small payments for his clients, which gave him a steady income. However, Mullan spent more money than he had. He expected a huge payment if he could get the California public lands money.

California Governors George Clement Perkins and George Stoneman had reappointed Mullan as the state's agent. The state legislature had confirmed each appointment. But in 1886, Robert Gardner, a former California Surveyor General, started a campaign against Mullan. He accused Mullan of hiding the true amount of money the state could get. He said Mullan wanted to get rich himself. In spring 1886, former Governor Perkins wrote to Mullan. He said he had made a mistake in appointing Mullan and allowing such a large fee.

Mullan's job had not yet ended when Governor Washington Bartlett died on September 12, 1887. Robert Waterman became governor. In February 1888, Waterman threatened to end Mullan's job. Mullan wrote a book to defend his work. But Republican newspapers and Gardner claimed Mullan's appointment was wrong. They said the state's congressional representatives could have done the same work for free. On January 18, 1889, Waterman ended Mullan's job. Mullan believed the Democratic legislature would give him his job back. He moved to San Francisco to fight the charges. The state legislature investigated the appointments. In 1889, the investigation ruled that Governors Perkins and Stoneman had acted legally. Mullan remained dismissed, but he believed he was still owed fees for money already won.

Mullan had gotten $228,000 from the federal government for California's Civil War costs. Mullan was supposed to get $45,600. But the government's check arrived after the 1889 investigation. The state said Mullan was not owed the fee because payment was made after he was dismissed. Mullan sued. The case went to the Supreme Court of California. The court ruled that Mullan had no legal agreement with the state for any fees. Mullan then asked the state legislature to pay him anyway. The state legislature passed a bill to pay him in 1897, but Governor James Budd stopped it. The state legislature passed another bill in 1899, but Governor Henry Gage also stopped it.

California's actions encouraged Mullan's other clients. In 1894, Mullan won $400,000 for Nevada and $350,000 for Oregon. Both states quickly passed laws. These laws made the United States Department of the Treasury send checks directly to the state. This bypassed Mullan and denied him any commission.

Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions

In March 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant announced his "Peace Policy." This policy changed how the government worked with Native Americans. Instead of fighting tribes, the government would establish reservations. Tribes would be cared for, educated, and housed. In the past, Indian agents were often corrupt. Grant's new policy used Christian missionaries as agents. The hope was that priests and nuns would be honest. In April 1869, Congress created the Board of Indian Commissioners. This board oversaw Christian missions and reservation work. Because of strong anti-Catholic feelings, only Protestants were appointed to the Board. Catholic missions were allowed at only 7 of 73 Indian agencies.

In response, the Catholic Church created the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions (BCIM) in 1874. This group lobbied the government for more access to reservations. It was reorganized in 1879. Leaders from the Catholic Archdioceses of Baltimore and Philadelphia led the BCIM. A commissioner (a non-religious person) acted as the group's lobbyist and fundraiser in Washington, D.C.

Retired Brigadier General Charles Ewing was the Commissioner for Indian Missions. He died suddenly in June 1883. Father Jean Baptiste Brouillet, a friend of Mullan's, wanted Mullan to be the new commissioner. Mullan knew the West well. He was friends with many Native Americans. He was also influential in Washington, D.C. James Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore, approved Mullan's appointment in October 1883.

Mullan was a dedicated and effective commissioner. He attended almost every meeting. He spent months each year visiting schools and reservations. He raised a lot of money. He also published a book praising the organization's work. By 1886, the number of Catholic schools had increased from 18 to 27. Mullan had convinced the government to increase student funding. While traveling, Mullan also visited western Montana for the first time since building the Mullan Road. Henry Villard, president of the Northern Pacific Railway, invited Mullan to a special event. On September 8, 1883, a gold spike was driven at Montana's Clark Fork River. This marked the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway.

Mullan's role with the BCIM lasted only two and a half years. Father Brouillet died in February 1884. In May 1884, Archbishop Gibbons named Father Joseph Stephan to lead the BCIM. Mullan and Father Stephan did not get along. In fall 1884, Father Stephan tried to take away Mullan's authority. Mullan protested, and the archbishops gave him back his power. But their relationship got worse. In September 1886, Mullan pushed for a financial investigation of a Catholic mission. This mission was outside the BCIM's control. It was also overseen by Bishop Martin Marty, Father Stephan's mentor. Father Stephan then accused Mullan of several wrongdoings. Archbishop Gibbons supported Stephan. Mullan had challenged a bishop's ethics. He had also hurt the Catholic Church's reputation with donors. Mullan was asked to resign, but he refused. Mullan attended his last BCIM meeting in March 1887. When the organization met again in July, Mullan's job no longer existed due to changes in their rules.

Later Years and Death

Even after losing his job as California's agent, Mullan continued to spend too much money into the 1890s. When his mother died in 1888, Mullan gave his share of her estate to his two younger sisters. He and his wife lived in a nice home in Washington, D.C., with two servants. By 1891, Mullan was having money problems. He tried to get back pay from the War Department but failed. Even so, when his brother Ferdinand died in 1892, John gave his share of the estate to his sisters.

Mullan's wife, Rebecca, died in September 1898. John Mullan became ill that same year. He was very weak and had trouble sleeping and eating. He lost a lot of weight. He spent most of 1898 and 1899 under a nurse's care. He could no longer live alone and moved in with his two daughters. He spent his time reading. He would sometimes visit his sisters in Baltimore or Annapolis for months. Mullan had a stroke in 1904. This left his left arm paralyzed and affected his right arm's movement.

Mullan could not continue lobbying for the money he was owed. He asked his daughter Emma to move to California in 1905 and continue his efforts. She did, and that year, a bill passed giving Mullan $45,000. Governor George Pardee was facing criticism. He decided to give Mullan only $25,000. Emma accepted the first payment. But she took legal action to get the full $45,000. State courts ruled that the governor could not change the law. They awarded Mullan the full $45,000 in 1910.

Despite his poor health, Mullan continued to earn some money. He did limited legal work for miners and farmers. He also worked for the Catholic Church. But this did not bring in enough money. His daughter, Mary, got a job as a stenographer with the War Department. She earned $900 a year. But this was not enough for Mullan's large debts. She resigned in late 1903. Around 1905 or 1906, Emma and May Mullan started a laundry business. It specialized in fine fabrics, furs, and carpets. It was called the DeSales Hand Laundry.

John Mullan sued the U.S. government on behalf of Oregon. He demanded that the government pay Oregon $690,000. This was for costs the state had during the Civil War. He won the case, but Oregon refused to pay him. Emma Mullan then went to Oregon. In 1907, the state legislature passed a bill. It awarded John Mullan $9,465. That same year, Mullan made a new will. He asked his sisters to give his share of his father's estate to his children.

Death

Mullan's health got much worse in 1907. He had to use a wheelchair. Later, he was confined to bed. Emma had married and moved to California. May Mullan took an apartment in Washington, D.C. She and her father lived there until he died.

Mullan's health declined quickly in December 1909. He died at May Mullan's home in Washington, D.C., on December 28, 1909. His funeral was held at St. Mary's Church in Annapolis. He was buried at St. Mary's Cemetery next to his parents and brothers. His brother, Dennis, and two sisters, Annie and Virginia, survived him. His son, Frank, and daughters Emma and May also survived him.

At the time of his death, Mullan had no money.

Personal Life

John Mullan's father, John Mullan Sr., died in Annapolis on December 23, 1863. His mother, Mary Bright Mullan, died on November 8, 1888.

John Mullan met his future wife, Rebecca Williamson, in Baltimore in 1856. They married on April 28, 1863. While living in San Francisco, they had five children. Rebecca and the children traveled to Europe in June 1885. John Mullan joined them in late 1886. The family did not return to the United States until 1887. Rebecca died at their home in Washington, D.C., on September 4, 1898. She was buried in Bonnie Brae Cemetery in Baltimore.

The Mullans had five children, but two died as babies. Their oldest surviving child, Emma Verita, was born in San Francisco in 1869. She married George Russell Lukens, a California state senator. She died without children in San Francisco on March 20, 1915. She was buried at Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery. Their second oldest surviving child, Mary Rebecca (known as "May"), was born in San Francisco in 1871. She married Henry Hepburn Flather, a banker. They lived in Georgetown in Washington, D.C. May Mullan died on December 31, 1962. She was buried at New Cathedral Cemetery in Baltimore. The Mullans' youngest surviving child, Frank Drexel, was born in San Francisco in 1873. He died on February 18, 1936, from a heart attack. He was buried at Bonnie Brae Cemetery near his mother.

John Mullan held some views that are considered racist today. He believed that government should be run "by white men, for the benefit of white men." He opposed Asian immigration, except for certain labor purposes. He also opposed Asian immigrants becoming citizens. Historian Keith Petersen has stated that Mullan's opinions were "vile" even for his time.

John Mullan III and Peter Mullan

While Mullan was with Colonel Wright during the Coeur d'Alene War, he became the informal guardian of an orphaned Yakima boy. On August 24, three young Native American boys were captured. They said they were Yakimas who had been enslaved. Wright sent the two older boys to Fort Walla Walla. Mullan convinced Wright to let him care for the youngest boy, who was about 14 years old. The boy, whom Mullan named John, stayed with Mullan's brother at Mullan's Walla Walla farm until 1864. After John Mullan Jr. lost the farm, the boy's location is unknown.

Oral stories in the Spokane area tell a different account. This tradition says that in fall 1853, John Mullan met and married Mary Ann Finley. She was part Native American. On June 9, 1855, Mary Ann died giving birth to a son named Peter Mullan. Some historians believe Peter Mullan was not John Mullan's child. They think a full-blood Native American was Peter's father. Mullan biographers Louis C. Coleman and Leo Rieman came to similar conclusions. However, historian Keith Petersen believes it is possible that Mullan was Peter Mullan's biological father. He also thinks Peter Mullan is not the same person as John Mullan III.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |