Butterfield Overland Mail facts for kids

"The Overland Mail Coach," illustration from Arizona, As It Is (1877)

|

|

| Industry | Postal service |

|---|---|

| Headquarters |

United States

|

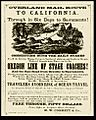

The Butterfield Overland Mail was a famous stagecoach service in the United States. It ran from 1858 to 1861. This service carried both passengers and U.S. Mail. It connected the eastern cities of Memphis, Tennessee and St. Louis, Missouri, to San Francisco, California, in the west.

The routes from Memphis and St. Louis met at Fort Smith, Arkansas. From there, the stagecoaches traveled through Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. The journey ended in San Francisco. In 1857, the U.S. government decided to create this mail route. It was a big step for connecting the country. In 2023, this historic route was named a national historic trail.

Contents

How the Mail Service Started

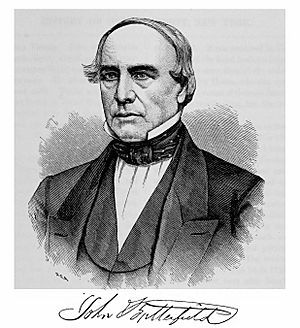

John Butterfield: The Man Behind the Mail

John Butterfield was born in New York in 1801. He started working with stagecoaches around 1820. He began as a driver and quickly learned the business.

Later, John Butterfield started his own stagecoach lines. He became very successful in New York. By 1857, he had 37 years of experience. This long history helped him win the big government contract.

Winning the Overland Mail Contract

In the 1840s and 1850s, people wanted better ways to communicate across the United States. Connecting the East and West Coasts was a big goal. The government decided to create an overland mail route.

In April 1857, the Post Office asked companies to bid on the mail service. Many experienced stagecoach operators applied. John Butterfield won the contract. His company was officially called the Overland Mail Company.

This was the longest mail contract ever given in the United States. It was worth $600,000 a year. John Butterfield was the president. Many of the main owners were also from New York, near Butterfield's home. The Postmaster General, Aaron Brown, chose Butterfield because he believed Butterfield had the most experience.

The chosen route was called the Oxbow Route. It was about 600 miles longer than other routes. However, it had one big advantage: it was usually free of snow. This made it a more reliable path for mail and passengers.

The Route and Its Builders

The contract for the Butterfield Overland Mail started on September 16, 1858. The route was split into eastern and western parts. El Paso, Texas was the middle point. Each part had smaller sections, managed by a superintendent.

Building the Butterfield Trail

John Butterfield chose two of his most trusted employees to set up the trail. These were Marquis L. Kenyon and John Butterfield Jr. In 1858, they helped pick the route and locations for the stage stations. Kenyon had a lot of experience with stagecoaches.

Kenyon traveled the entire route from East to West. He surveyed it and chose the best path. He then got all the supplies needed. John Butterfield Jr. also helped mark the stations and organize the work. He even drove the first stagecoach over the route.

The Butterfield Trail helped connect the East and West. It also made it easier for people to move and settle in the West. The company improved the trail by adding water sources and stations. Even after the service stopped in 1861, the trail remained important. People still call it "The Butterfield Trail" today.

The section from San Francisco to Los Angeles was already somewhat developed. But east of Los Angeles, Kenyon faced a harder job. He had to build the trail through open desert.

Improvements Along the Trail

Many parts of the trail were improved. New roads were built in Texas, saving many miles. For example, a new road from Grape Creek to Concho River saved 30 miles. The New Pass between Los Angeles and Fort Tejon in California was also made better.

When the service started, there were 139 stations. By the time it ended, there were 175. These new stations helped the mail line. They often grew crops, which also helped supply the service.

Water was very important on the trail. Many waterholes were dug out to hold more water. Cisterns were built at some stations. Water wagons carried water from far away to fill these cisterns. At Hueco Tanks in Texas, the tanks were made larger to hold a year's supply of water.

Bridges were also built. There was a heavy bridge over the Blue River in Indian Territory. Two bridges were built in Arizona, across the San Simon River and the San Pedro River.

President James Buchanan congratulated John Butterfield in 1858. He said the trail was a "glorious triumph for civilization and the Union." He believed settlements would follow the road. The improved trail also helped other mail lines. It made travel safer and easier for many people moving West.

| Division | Route | Miles | Hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Division 1 | San Francisco to Los Angeles | 462 | 80 |

| Division 2 | Los Angeles to Fort Yuma | 282 | 72.2 |

| Division 3 | Fort Yuma to Tucson | 280 | 71.5 |

| Division 4 | Tucson to Franklin | 360 | 82 |

| Division 5 | Franklin to Fort Chadbourne | 458 | 126.3 |

| Division 6 | Fort Chadbourne to Colbert's Ferry | 282+1⁄2 | 65.3 |

| Division 7 | Colbert's Ferry to Fort Smith | 192 | 38 |

| Division 8 | Fort Smith to Tipton | 318+1⁄2 | 48.6 |

| Division 9 | Tipton to St. Louis by railroad | 160 | 11.4 |

| Totals | 2,795 | 596.3 |

Connecting San Francisco to Memphis

The route from San Francisco to Fort Smith was the same for both eastern destinations. Travel time from Fort Smith to Memphis was similar to St. Louis. The southern route often used different ways to travel. This was because the Mississippi River and its branches were wild back then.

There was no bridge at Memphis. The mail sometimes traveled by steamboat on the Mississippi River. It would go up the Arkansas River to Little Rock. From there, it would switch to stagecoach. If the rivers were too low, the entire trip across eastern Arkansas was by stagecoach.

Butterfield's Vehicles

No one on a Butterfield stagecoach was ever killed by outlaws. However, some people died in accidents. These were often caused by wild mules or horses. Butterfield's stages were not allowed to carry valuable items like money or jewelry. Because of this, they didn't have "shotgun" riders.

A passenger named Waterman L. Ormsby asked a driver if he had any weapons. The driver said, "No, I don't have any; there's no danger." But many passengers carried weapons, especially in areas where Comanche and Apache tribes lived.

Mail Stagecoach

These stagecoaches were strong and comfortable. They had padded seats and decorated wooden panels. They often had window openings, but western models for rougher trails had no glass. The roof was strong enough for luggage. A canvas boot at the back held luggage and mailbags. Mail stagecoaches had a larger compartment for mail under the driver's seat. Butterfield used these stagecoaches on about 30% of the trail, mostly at the eastern and western ends.

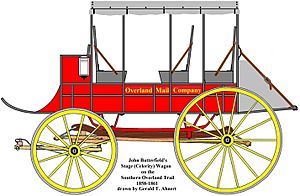

Stage (Celerity) Wagon

Celerity means 'swiftness'. These wagons were lighter than stagecoaches. They were designed for rougher trails, sand, and steep hills. They were open on the sides, with no doors or windows. They often had a canvas top and curtains that could be rolled down for protection from dust.

Butterfield's Overland Mail Company used these wagons on 70% of the trail. This was the 1,920-mile section from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Los Angeles, California. Some people called them "mud wagons," but the manufacturers didn't use that name.

Making the Stages

Newspapers reported in 1858 that J.S. & E.A. Abbot Co. in New Hampshire made Butterfield's stagecoaches and wagons. Butterfield ordered 100 stages. These were either put into use or sent to stations along the trail.

A report from September 1858 said the road was stocked with "substantially-built Concord spring wagons." Another article said that 60 more wagons were coming. These "Concord" stagecoaches were well-known for their quality.

A passenger described the celerity wagons: "They are made much like the express wagons... only they are heavier built, have tops made of canvas, and are set on leather straps instead of springs." He also noted that each wagon had three seats that could fold down to make a bed for four to ten people.

The same stagecoach or driver was not used for the entire 2,700-mile trip. They were changed often to prevent fatigue and breakdowns. Butterfield bought horses, mules, and a wagon or coach for every 30 miles of the route. Stations were set up for changing animals and feeding them.

About 34 mail stagecoaches were used on the more settled parts of the trail. About 66 celerity wagons were used on the frontier sections.

Other Wagons

Butterfield also used water wagons and freight wagons. Water wagons were very important. To make the trail straighter, stations were built away from natural water sources. Water wagons then brought water from distant springs to fill cisterns at these stations. This was expensive but necessary.

For example, in Texas, a desert section was 75 miles wide. Water wagons with large tin boilers, like steamboat boilers, carried water to stations. These trains ran regularly, filling large reservoirs for passengers, employees, and animals.

Stage Drivers and Animals

Many of Butterfield's employees, including the stage drivers, were from New York. A census from 1860 in Tucson showed that many employees were born in New York. Passengers often found the employees polite and helpful. Most drivers were experienced. Some were a bit reckless, but generally, they were careful.

Each stagecoach usually had four horses or mules. Many reports describe problems with the wild mules and mustangs used between Fort Smith and Los Angeles. These animals were often unbroken. Despite this, the stages usually kept to their schedule.

One passenger described how difficult it was to get the wild horses to move. People had to stand at the horses' heads until the driver was ready. Then, they would let them go, and the horses would start running. As they traveled further, the animals became tamer.

Sleeping on the Stages

The 25-day trip did not stop for passengers to sleep. They had to sleep inside the moving stagecoaches. Many passengers shared funny stories about trying to sleep. A common problem was losing their hats because the open-sided celerity wagons offered little protection from the wind.

Historian Frank Norris said that pulling up to a Butterfield stage station was like making a "NASCAR pit stop." This means they were very fast and efficient at changing horses and getting back on the road.

Surviving Butterfield Stages

When Butterfield's service ended in March 1861 due to the Civil War, many stages were taken by the Confederate Army. Some equipment was moved to the central trail to continue the mail contract. Only enough stages made it to operate the line from Salt Lake City, Utah, to western Nevada.

One employee, Edwin R. Purple, helped move 18 stage wagons and 130 horses from Arizona to Salt Lake City in 1861. It is thought that many original stagecoaches were bought by movie companies in the 1930s to 1950s. Many were destroyed in movie scenes showing attacks.

How the Service Operated

Butterfield's Overland Mail Company had a six-year contract starting September 16, 1858. The first stagecoach going east left San Francisco just after midnight on September 14, 1858. The mail reached St. Louis in about 24 days. The first stage going west left Tipton, Missouri, on September 16, 1858. The first 160 miles from St. Louis to Tipton were covered by railroad.

The company made two trips a week. At first, mail left St. Louis and San Francisco every Monday and Thursday. Later, San Francisco departures changed to Monday and Friday. The fare to the end of the railroad line was $100, later increasing to $200.

Pony Express and the Overland Mail

When the Overland Mail Company's contract moved to the Central Overland Trail, the Pony Express was added. This happened on March 12, 1861. The new contract required a semi-weekly Pony Express service. It had to deliver mail in 10 days for eight months of the year and 12 days for four months (winter). The government received 5 pounds of mail for free. The public could be charged up to $1 per half ounce for letters. The total payment for the service was $1,000,000 per year.

The Pony Express stopped running before the contract ended. This was because the telegraph line was completed on October 24, 1861.

Near the end of Butterfield's service on the Southern Overland Trail, he was voted out as president. This was because the company wasn't making enough money for the owners. However, he remained an owner.

Moving to the Central Overland Trail

The Butterfield Overland Mail Company was ordered to move its operations to the Central Overland Trail. This was because the American Civil War was about to begin. The last mailbag left St. Louis, Missouri, on March 18, 1861. It arrived in San Francisco on April 13, 1861.

Some employees moved with the company to the Central Overland Trail. William Buckley, a superintendent, continued his role. Even though William B. Dinsmore became the new president, employees still called it "Butterfield's."

Only enough equipment and employees were moved to stock the trail from Carson City, Nevada, to Salt Lake City, Utah. The new route was sometimes called the "Butterfield new route."

After the Butterfield route was abandoned in the South, some parts were used by other mail services. However, these had limited success due to the Civil War. Wells Fargo continued its stagecoach runs in northern areas until the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869.

Several battles during the Civil War happened near Butterfield mail posts. These included the Battle of Stanwix Station and the Battle of Picacho Pass. There were also clashes between Apache tribes and soldiers on the route. Confederates tried to keep some stations open while destroying others to stop Union forces.

Modern Remnants

Today, you can still see parts of the Butterfield Overland Mail route.

- Two stage stations survive in San Diego County, California: Oak Grove Butterfield Stage Station and Warner's Ranch. Both are National Historic Landmarks.

- Elkhorn Tavern in Pea Ridge National Military Park was rebuilt after the Civil War. It's on a surviving section of the trail called Old Wire Road in Northwest Arkansas.

- In Arkansas, Pottsville has Potts Inn, a popular stop from 1859. It is now a museum.

- Near El Paso, Texas, at Hueco Tanks, you can still see the remains of a stagecoach stop.

- On Guadalupe Peak in Guadalupe Mountains National Park, there's a stainless steel pyramid. It was put there in 1958 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Butterfield Overland Mail. The trail passed south of the mountain.

National Historic Trail

On March 30, 2009, President Barack Obama signed a law to study making the trail a National Historic Trail. The National Park Service finished its study in 2018. They decided it would be a good idea to make it part of the National Trails System.

In 2022, Congress passed a bill to officially name it the Butterfield Overland National Historic Trail. The trail covers 3,292 miles across eight states. The National Park Service will create a plan to manage it.

Images for kids

-

Butterfield marker in Sherman, Texas

-

Fort Chadbourne reconstructed stage station

-

Fort Belknap (Texas) Historical Marker

-

Guadalupe Peak summit, with a pyramid commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Butterfield Overland Mail

See also

- Southern Emigrant Trail

- San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line

- Butterfield Overland Mail in California

- Butterfield Overland Mail in New Mexico Territory

- Butterfield Overland Mail in Texas

- Butterfield Overland Mail in Indian Territory

- Butterfield Overland Mail in Arkansas and Missouri

- Butterfield Overland Despatch, an unrelated company

- Pony Express

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Confederate States

- Stockton – Los Angeles Road

- Apache Pass Station

- Butterfield Overland Mail Company Los Angeles Building

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |