Treaty of Point Elliott facts for kids

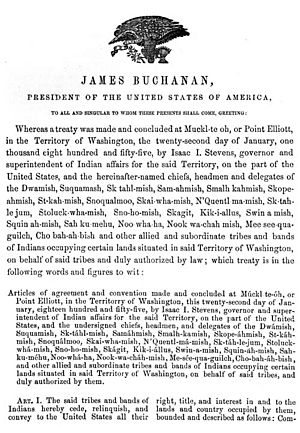

The Treaty of Point Elliott was an important agreement signed on January 22, 1855. It was made between the United States government and many Native American tribes in the Puget Sound area of what was then the new Washington Territory. This treaty was one of about thirteen similar agreements between the U.S. and Native Nations in the region.

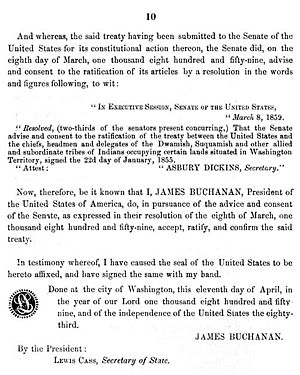

The treaty was signed at a place called Muckl-te-oh, which is now Mukilteo, Washington. It was officially approved by the U.S. government in 1859. During the years between the signing and approval, there was still fighting in the area. European-American settlers had been moving into the region since about 1845.

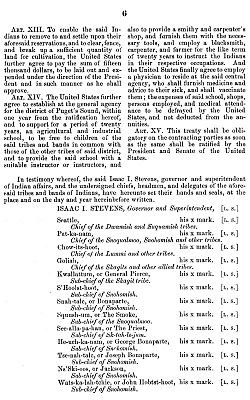

Key people who signed the treaty included Chief Seattle (from the Duwamish and Suquamish tribes) and the governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens. Leaders from tribes like the Duwamish, Suquamish, Snoqualmie, Snohomish, Lummi, Skagit, and Swinomish also signed.

The treaty created several reservations for some tribes, including the Suquamish (Port Madison), Tulalip, Swinomish, and Lummi reservations. However, reservations were not set up for the Duwamish, Skagit, Snohomish, and Snoqualmie peoples. A very important part of the treaty was that it guaranteed Native Americans would keep their traditional fishing rights.

Contents

Why the Treaty Was Needed

Before the treaty, a law from 1834 called the Nonintercourse Act said that White Americans could not go into Native American territories. But later, the Oregon Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 allowed European-Americans to settle in the Oregon Territory, which included what became Washington Territory.

This law was going to end on December 1, 1855. Settlers had to claim their land by that date. This meant that White leaders wanted to sign treaties with Native Americans very quickly. They wanted to make it legal for settlers to develop the land.

Under these settlement laws, a single male settler could get 320 acres of land for free. A married couple could get 640 acres. Settlers who arrived before 1850 could even get 640 acres. These land claims were often made just by moving onto the land, sometimes with the backing of local militias.

Native Americans were worried and upset by settlers moving onto their lands. Sometimes, they responded with raids or uprisings.

Native American Views on Land

Most Native leaders were willing to sell some of their land. However, they had very different ideas about land use compared to European-Americans. They did not understand the European-American idea of owning land as private property. They also did not want to be moved far away from their homes in the Puget Sound area.

The U.S. government and Native American tribes are considered co-equal "sovereign entities." This means they are like independent nations. Tribal governments existed long before the United States. A basic rule is that tribes keep all their original sovereign rights and powers unless they clearly give them up or they are taken away by law.

Treaties Are Important Agreements

The U.S. Constitution says that all treaties made by the United States are the "supreme law of the land." This means they are very important and must be followed.

Since the late 1900s, Native American groups have challenged many treaties and land agreements in court. The Supreme Court has ruled that treaties should be understood as the Native Americans would have understood them when they signed. The Court also said that treaties are a "grant of rights from the Indians, not to them." This means that Native Americans kept any rights they did not specifically give away. For example, they kept their traditional rights to fish and hunt on ceded land unless the treaty clearly said they could not.

A treaty that is broken is not automatically canceled. Only a new treaty or agreement can change the original one. Treaties are considered as old and important as the U.S. Constitution itself.

Native American tribes often did not agree with how European law reduced their self-governance. They have argued that they kept more sovereign powers than federal law admits. This has led to disagreements between tribal, federal, and state governments about who has power and control.

Governor Stevens' Role

Isaac Stevens, the Governor of Washington Territory, often made promises to tribal leaders by speaking to them. However, what his office wrote down was sometimes different from what he said. Native tribes had an oral culture, meaning they relied on spoken words, so they trusted his promises. Years later, a judge named James Wickerson said that the treaties Stevens approved were "unfair, unjust, ungenerous, and illegal."

Native people in the area had dealt with the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) for 30 years. The HBC was known for being tough negotiators but also for sticking to their agreements and treating everyone fairly. This was different from Governor Stevens and his staff.

Governor Stevens ignored instructions from the federal government. He was supposed to focus only on areas where Native Americans and settlers were living very close to each other. Instead, he tried to settle Native issues for the entire territory, which angered many Native groups.

Historians suggest that Stevens sometimes appointed certain chiefs to make it easier to achieve his goals.

Stevens' Policy Goals

Governor Stevens had a clear plan for Native Americans:

- Gather Native Americans onto a few reservations.

- Encourage them to farm and live in a more "civilized" way.

- Pay for their lands with blankets, clothing, and useful items over many years, not with money.

- Provide them with schools, teachers, farmers, tools, blacksmiths, and carpenters.

- Stop wars and arguments among the tribes.

- Try to stop the use of alcohol.

- Allow them to keep their right to fish at their usual places, hunt, gather berries and roots, and graze their animals on unoccupied land as long as it remained empty.

- Later, the land on the reservations would be divided among individual families.

Native American tribes believed the treaties became official as soon as their leaders signed them. However, U.S. law required Congress to approve all treaties. Even though settlers started moving in around 1845, Congress did not approve the Treaty of Point Elliott until April 1859. This delay made the settlement legal only after years had passed. The U.S. government never fully carried out the treaty's promises for the Duwamish and several other tribes.

Who Was Involved in Negotiations

U.S. Government Staff

Some of the key people working for the U.S. government during the treaty negotiations included:

- James Doty, Secretary

- George Gibbs, Surveyor and record keeper

- B. F. Shaw, Interpreter

Native American Leaders and Tribes

Governor Stevens appointed some of the chiefs who signed the treaty, even though the treaty stated they were "duly authorized" by their tribes.

Tribes That Signed

Many tribes signed the Treaty of Point Elliott. Some of these included:

- Dwamish (Duwamish)

- Suquamish

- Skokomish

- Sammamish

- Smulkamish and Skopamish (parts of the Muckleshoot people)

- Snoqualmie

- Skykomish

- Snohomish

- Lummi

- Skagit

- Kikiallus

- Swinomish

- Sauk-Suiattle

Tribes That Did Not Sign

Some tribes, like the Nooksack, Semiahmoo, Lower Puyallup, and Quileute, did not take part in the treaty meetings. The rights of the Nooksack were signed away by the Lummi chief Chow-its-hoot, even though the Nooksack were not there.

The Samish tribe was present, but their name was accidentally left out of the final treaty document. Several tribes, such as the Duwamish and Snohomish, are still working to get official federal recognition today.

Important Parts of the Treaty

The treaty has several important sections, called "articles." Here are a few:

- ARTICLE 5: This article says, "The right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory."

* This part was very important later on. In the 1970s, Native Americans went to court because they were being stopped from fishing in certain places. A judge named George Boldt ruled in the Boldt Decision (1974) that Native Americans had a traditional right to fish and hunt because the treaty did not specifically take those rights away.

- ARTICLE 7: This article gave the U.S. President the power to move Native Americans from their special reservations to a larger, general reservation if he thought it was best for the territory and the Native Americans. It also said he could divide reservation lands into smaller lots for individual families.

* Native American lawyers were concerned about this part during the negotiations.

- ARTICLE 12: This article stated that the tribes could not trade at Vancouver Island or outside U.S. lands. It also said that Native Americans from other countries could not live on the reservations without permission.

You can read the full treaty on Wikisource.

What Happened After the Treaty

For a long time, tribes in the Pacific Northwest relied on salmon and other fish for food. After 1890, the state and federal governments started to limit Native American fishing more and more. This was because commercial and sports fishing, mostly by European-Americans, grew very popular. State rules against Native fishing became even stricter through the 1950s.

In the 1960s, Native American tribes in the Northwest started protesting these limits with "fish-ins." They peacefully outsmarted the police, which brought a lot of attention from the media. The Boldt Decision in 1974 confirmed their traditional fishing rights. Even after this ruling, there were still efforts by the state to limit their fishing and resistance from non-Native fishermen. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld Judge Boldt's ruling in 1979.

Today, regional fisheries councils exist. Native Americans, sports fishermen, commercial fishermen, and federal scientists work together. They check how many fish are available each year, plan for protecting fish, and decide how to share the fish harvests.

During the same time, some Native American tribes that lived outside reservations and were not officially recognized by the federal government, like the Nooksack, Upper Skagit, Sauk-Suiattle, and Stillaguamish people, gained federal recognition in the 1970s. This helped them get financial support, including aid for their children's education. Federal courts, however, did not recognize the Snohomish, Steilacoom, and Duwamish tribes as official governments.

Point Elliott Treaty Monument

In 1930, a monument for the Point Elliott Treaty was put up in Mukilteo, Washington. It was built by a group called the Marcus Whitman Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

The monument is a large granite slab, about 6.5 feet by 3 feet, and 15 inches thick. It has a bronze plaque with words written by Edmond S. Meany. The monument celebrates the signing of the treaty, but the exact spot where it was signed is not known. The Point Elliott Treaty Monument was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 14, 2004.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Tratado de Point Elliott para niños

In Spanish: Tratado de Point Elliott para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |