Snohomish people facts for kids

| sduhubš | |

|---|---|

A map of Snohomish territory in 1855 with historical village locations

|

|

| Total population | |

| ~5,100 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Snohomish County, Washington | |

| Languages | |

| English, Lushootseed | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional folk religion, Christianity, incl. syncretic forms | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Lushootseed-speaking peoples, esp. the Skykomish |

The Snohomish people (Lushootseed: sduhubš SDOH-hohbsh) are a group of Native people from the Puget Sound area in Washington State. They are part of the larger Coast Salish family. Most Snohomish today are members of the Tulalip Tribes of Washington. They live on the Tulalip Reservation or nearby. Some Snohomish are part of other tribes, and some are members of the Snohomish Tribe of Indians, which is not officially recognized.

Long ago, the Snohomish lived in a large area. This included the Snohomish River, parts of Whidbey and Camano Islands, and the nearby coast. They had at least 25 villages. In 1855, they signed the Treaty of Point Elliott. This treaty moved them to the Tulalip Reservation. Life on the reservation was hard. There wasn't enough land, and the government had strict rules. Because of this, many Snohomish people left the reservation.

Today's Snohomish people come from several groups, like the N'Quentlmamish and Sdodohobsh. Each group used to be independent. But they all shared a strong culture and called themselves Snohomish. They knew their land well and formed strong friendships with other groups. They did this through marriage and talking things out. This helped them have influence far beyond their own lands.

In the summer, they traveled to hunt, gather plants, and fish. Winter was a time for religious events and ceremonies. Today, the Snohomish still hold potlatches. They also keep other traditions alive, like using canoes, fishing, hunting, and gathering materials for crafts. The Snohomish traditionally spoke a dialect of the Lushootseed language. Now, most speak English. The Tulalip Tribes are working hard to bring the Lushootseed language back. They also teach other traditional ways, known as x̌əč̓usadad.

Contents

Understanding the Name "Snohomish"

The name "Snohomish" comes from the Lushootseed word sduhubš. When Europeans first met the Snohomish, their name sounded like snuhumš. This is how the English word "Snohomish" came to be. Over time, the Lushootseed language changed, but the English name stayed the same.

The name sduhubš used to mean all the people living in certain villages. These villages were on southern Whidbey and Camano Islands, Hat Island, and along the coast from Warm Beach to Mukilteo. They also lived along the Snohomish River up to Snohomish City. There were many smaller groups and villages, but they all felt connected as Snohomish.

People have different ideas about what sduhubš means. The Tulalip Tribes and some experts say it means "many men" or "lots of people." William Shelton, an important Snohomish leader, said it meant "lowland people." Today, Snohomish County, the city of Snohomish, and the Snohomish River are all named after the Snohomish people.

Snohomish Family Groups

The Snohomish are part of the Southern Coast Salish people. This group includes all the people who speak Lushootseed. The Snohomish today come from several groups. These include the Snohomish proper, the Sdodohobsh, and the N'Quentlmamish. Some experts also consider the Skykomish and Sktalejum to be part of the Snohomish family. This is because they were very close.

Each of these groups was once independent. They were not seen as one big Snohomish group like they are today. Each group also had several independent villages. These villages were connected by shared rivers and a network of family friendships. People from island villages were called čaʔkʷbixʷ. This was a way to describe where they lived, not their family group.

Whidbey Island Snohomish

The dəgʷasx̌abš were also called the Whidbey Island Snohomish. They were known for being wealthy and famous throughout Puget Sound. They had several villages on the southern part of Whidbey Island.

Quil Ceda People

The Quil Ceda people (Lushootseed: qʷəl̕sidəʔəbš) lived in many villages near Quil Ceda Creek. This included a village at Priest Point.

Upper Snohomish (Sdodohobsh)

The Sdodohobsh (Lushootseed: sduduhubš) were also known as the Upper Snohomish or Monroe people. They came from three villages near Monroe. Their name means "little Snohomish." They were seen as a lower-class group compared to the main Snohomish.

Pilchuck River People (N'Quentlmamish)

The N'Quentlmamish (Lushootseed: dxʷkʷiƛ̕əbabš) lived in villages along the Pilchuck River. Their land included the Pilchuck River area and Lake Stevens. They had two villages. They were also seen as lower-class by the Snohomish. They were part of the Treaty of Point Elliot. Their land was given up by Patkanim, a Snoqualmie leader.

Sktalejum People

The Sktalejum (Lushootseed: st̕aq̓taliǰabš) have been linked to the Snohomish, Skykomish, or Snoqualmie groups. Their three villages were on the Skykomish River. They were once a strong group. But smallpox diseases greatly reduced their numbers. They also signed the Treaty of Point Elliott.

Quadsack People

The Quadsack (Lushootseed: qʷacaʔkʷbixʷ) lived on Hat Slough. They had one village. They were closely related to both the Snohomish and the Stillaguamish. After the smallpox diseases, they became part of these larger groups.

Snohomish History

For thousands of years, the Snohomish lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering food. Before Europeans arrived, there were thousands of Snohomish people. In the early 1800s, diseases like smallpox and measles greatly reduced their population.

Around 1820, a huge landslide at Camano Head destroyed several Snohomish villages. A village on Hat Island was also wiped out by a large tidal wave from the landslide. The biggest Snohomish village, hibulb, was almost destroyed too. Hundreds of people died in this disaster.

Around 1824, the Snohomish were fighting with the Klallam and Cowichan people. They met John Work, a trader from the Hudson's Bay Company. Later, the Snohomish traded with the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Nisqually. In the early 1840s, Roman Catholic missionaries also came to their lands.

Treaty of Point Elliott

In 1855, a meeting was held at what is now Mukilteo, Washington. The governor, Isaac Stevens, wanted to create a treaty. This treaty would give the lands of the northern Puget Sound people to the United States. About 350 Snohomish people attended this meeting.

During the treaty talks, Governor Stevens made the Snohomish seem less important than the Snoqualmie. Patkanim, a Snoqualmie leader, signed the treaty for the Snohomish. The Snohomish people were very unhappy about this. Patkanim and nine Snohomish "sub-chiefs" agreed to give all Snohomish lands to the United States.

- S'hootsthoot

- Snahtalc (aka Bonaparte)

- Heuchkaman (aka George Bonaparte)

- Tsenahtalc (aka Joseph Bonaparte)

- Ns'skioos (aka Jackson)

- Watskalahtchie (aka John Hobststhoot)

- Shehtsoolt (aka Peter)

- Sahahhu (aka Hallam)

- John Taylor

During the Puget Sound War (1855-1856), the Snohomish stayed neutral. This made American officials upset. They wanted the Snohomish to help the American government. One official even suggested breaking up the tribe. During this time, the Snohomish were told to move to a temporary reservation on Whidbey Island. This was to keep them away from tribes fighting the Americans.

The treaty first planned for the Snohomish, Skykomish, Snoqualmie, and Stillaguamish to move to a temporary Snohomish reservation. But the treaty makers greatly underestimated how many people lived there. The land set aside was too small to support all four tribes.

Later, the Tulalip Reservation was created. It was meant to be a large area for all people in western Washington. The Snohomish reservation was included in the Tulalip Reservation. In 1873, the Tulalip Reservation was made even larger.

Life on the Reservation

The Tulalip Reservation was chosen for its timber and sawmill. But money was never given to fix the sawmill. In 1874, it became illegal for people on the reservation to cut their own trees. All work on the reservation was stopped. This caused many people to leave and find logging jobs elsewhere. Eventually, logging became legal again. But by 1883, most of the reservation's forests were gone.

Some parts of the reservation were swampland. The plan was for residents to drain it for farming. But the soil was poor, and little money was given for draining. Because of these problems, many people left.

The Tulalip Reservation was also very crowded. There simply wasn't enough land for everyone who was supposed to move there. By 1909, all the land on the reservation had been given out. Some people lost their land, and others never got any. Most Snohomish did move to Tulalip at first. But because of the lack of land, most returned to their traditional homes. In 1919, twice as many Snohomish lived off the reservation than on it.

The American government also had strict rules. They tried to stop people from speaking their traditional language and practicing their religion. This also made many people leave the reservation. In 2008, the Snohomish Tribe of Indians (an unrecognized group) had 1,200 members. As of 2023, the Tulalip Tribes have at least 5,100 members. Most of them are of Snohomish background.

Snohomish Lands and Villages

The main Snohomish land was the lower Snohomish River. This included parts of Snohomish, King, and Island counties. It stretched over Whidbey Island, Camano Island, Hat Island, and the eastern coast of Puget Sound. They also controlled the Snohomish River and parts of the Skykomish River.

The Snohomish knew their land boundaries very well. They respected the boundaries of other tribes. Friendships and alliances allowed groups to cross into each other's lands. The Snohomish shared parts of Whidbey Island with the Skagit, Kikiallus, Snoqualmie, and Suquamish tribes. They shared parts of Camano Island with the Stillaguamish, Snoqualmie, and Kikiallus. The Snoqualmie and Duwamish could visit Hat Island. Tulalip Bay was shared with the Stillaguamish and Snoqualmie. The southern Puget Sound coast was shared with their Duwamish neighbors. In return, these groups allowed the Snohomish to visit their lands for hunting, fishing, and gathering.

Snohomish Villages

The Snohomish and related groups lived in at least 25 permanent villages. Villages usually had at least one longhouse. Larger villages, like hibulb, also had smaller houses and a special potlatch house for ceremonies. Some villages, like hibulb, had tall cedar fences to protect them. Lower-class villages did not have these fences.

| Group | Name | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Snohomish

(sduhubš) |

šəƛ̕šəƛ̕šɬ | Bush Point, Whidbey Island | Three longhouses and a potlatch house. |

| dəgʷasx̌ | Cultus Bay | Five longhouses, two smaller houses, and a potlatch house. This was the main village for the Whidbey Island Snohomish. | |

| č̓əč̓ɬqs | Sandy Point, Whidbey Island | Known for its potlatch house. | |

| č̓əč̓əsəliʔ | Hat Island | Several longhouses. This village was destroyed by a tidal wave in the early 1800s. Later, it was a summer camping spot. | |

| x̌ʷuyšəd | Camano Head | Destroyed by a landslide in the early 1800s. After that, it was only a summer camping spot. | |

| dxʷtux̌ʷub | Warm Beach | A village with Snohomish, Stillaguamish, and Quadsack people. | |

| q̓ʷx̌ʷabqs | Tulare Beach | ||

| dxʷlilap | Tulalip Bay | There were four villages close together in the bay. | |

| č̓ƛ̕aʔqs | Priest Point | Three longhouses and a potlatch house. This was a lower-class village. | |

| Between č̓ƛ̕aʔqs and qʷəl̕sidəʔ | |||

| qʷəl̕sidəʔ | Quil Ceda Creek | A very old village with a potlatch house. Up to 30 houses and 5 villages were along the creek. | |

| sʔucid | South of the bridge over the creek | An old place for crossing the creek. | |

| dxʷqʷtaycədəb | Sturgeon Creek | At least one longhouse and a potlatch house. | |

| qʷəq̓ʷq̓ʷus | Upriver of the bridge over the creek, near a small bluff | At least one longhouse. | |

| Upriver from qʷəq̓ʷq̓ʷus | A village built after the treaty, with one longhouse. | ||

| hibulb | Preston Point, Everett | The main Snohomish village. It had four large longhouses, many small houses, and a big potlatch house. It was a very important village. | |

| sbadaʔɬ | Snohomish | A large village, number of houses unknown. | |

| N'Quentlmamish

(dxʷkʷiƛ̕əbabš) |

dxʷkʷiƛ̕əb | Pilchuck River, near the mouth | The main N'Quentlmamish village. |

| Machias | Two houses. | ||

| Sdodohobsh

(sduduhubš) |

səxʷtəqad | Three miles southwest of Monroe | A large potlatch house and at least three longhouses. |

| t̕aq̓tucid | Two miles southeast of Monroe | Four or five longhouses. | |

| bəsadsx̌ | Monroe | The main Sdodohobsh village. |

Snohomish Culture

Traditional Beliefs and Spirits

A main belief in traditional Snohomish religion is in spirit power or guardian spirit (sqəlalitut). Spirit powers helped in many ways, from daily tasks to fighting. For example, a hunter might sing their spirit song. If the spirit sang back, the hunt would be successful. Some jobs were only for those with certain helpful spirits.

Snohomish children were taught from a young age to go on a spirit power journey (ʔalacut). They would go to faraway places to receive a spirit power. Popular spots were Stevens Pass and Lake Getchel in the Cascades. Spirit quests usually happened in the spring, often during a storm. To get a spirit power, a person had to do something very hard. This often meant not eating, bathing many times a day, and diving deep into water. The harder the challenge, the more powerful the spirit they would get. Both women and men could get spirits, but men often got more powerful ones.

Winter was a time for many religious ceremonies. The winter spirit power ceremony (spigʷəd) was very important. In Snohomish belief, spirit powers travel the world but return in winter. When a spirit returns, a person feels sick and hears their spirit song. They would then hold a large ceremony, often for several days. They would sing, dance, and give gifts to friends and family. Friends were invited to help sing and dance. At the end of this ceremony, a person would usually hold a potlatch.

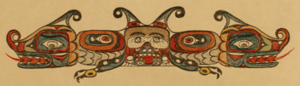

Snohomish religion also includes the sgʷədilič. This is a spirit shaped like a board. This tradition started in the Puget Sound area. A Snohomish woman was said to be the first to get it. The boards are painted red and black, about one and a half feet long, with a hole. This spirit helps people catch fish and find those lost in the woods. During the winter ceremony, people with this spirit hired four men to dance for them. The dances lasted four days and nights.

The most powerful spirit power was tiyuɬbax̌. This spirit helped people gain wealth and property. Someone with this spirit was said to receive more gifts at a potlatch. Another powerful spirit was tubšədad, a war spirit. People with this spirit were often famous warriors. Both these spirits were found only in deep water. The only spirit one never wanted to meet was the ʔayahus (Ayahos). This is a very powerful elk-snake spirit that lives in the forest. Hunters who follow this spirit are believed to die soon after meeting it.

Shamans, also called doctors (dxʷdahəb), had special spirits. These spirits could be used to heal or hurt people. Shamans did not have a winter dance. Their spirits stayed with them all the time. Shamans could cure many things. But those hurt in war could only be cured by their own spirit powers. Shamans could also bring back a person's spirit power if it was stolen.

After colonization, many Snohomish also joined the Indian Shaker Church. This is a Christian religion that mixes traditional beliefs. A Shaker church was built at Tulalip.

Traditional Homes (Architecture)

The main home for the Snohomish was the winter longhouse. Longhouses were often 100 to 200 feet long. The Snohomish had two types of longhouses: those with slanted shed roofs and those with triangular gable roofs. Longhouses were built from long cedar planks tied to strong posts. Inside, houses were divided into rooms for each family. The oldest family member carved and painted the house posts. Cattail mats hung on the walls for warmth and storage. Sleeping platforms were along the walls. Above them were shelves for food, blankets, and other items. Fireplaces were on the sides of the house, not in the middle. This allowed people to move easily through the house.

A copy of a traditional shed-roof longhouse was built at the Hibulb Cultural Center. It is used for gatherings and storytelling. The Gathering Hall at Tulalip Bay is also designed like a traditional gable-roof longhouse.

The people who built a longhouse owned it. Many longhouses were owned by the whole community. In larger longhouses with separate rooms, each room was owned by one or more families. Other longhouses were owned by just one man and his family.

Wealthier communities sometimes built special potlatch houses. Any longhouse could be used for potlatches. But large, rich communities often built houses just for these ceremonies. These houses were built like regular homes but usually had no inside walls. The largest Snohomish potlatch house was at dxʷlilap. It was a large shed-roof house, 115 feet long and 43 feet wide, with ten carved posts.

The Snohomish also built smaller, temporary summer homes. These were square-shaped, like a lean-to or with a gabled roof. They were made of a frame covered with large, waterproof mats. Usually, only one family lived in a summer house.

Food and Sustenance

Before colonization, there was always plenty of food in Puget Sound. The Snohomish had a healthy and varied diet. They caught many types of salmon, trout, sturgeon, and flounder in lakes, rivers, and saltwater. They gathered clams, cockles, and mussels on the coast. They hunted bear, deer, beaver, elk, goat, duck, and goose in the forests. Fish was mainly dried. Meat was smoked and dried.

Fishing was very important to the Snohomish. They had many traditional ways to catch fish in rivers and saltwater. A famous river fishing method used weirs (Lushootseed: stqalikʷ). Weirs were built across a river. People could walk on a platform and lower a dip-net (luk̓ʷ) into the trapped fish. They also used traps, hooks, and spears. At night, they used flares made of pine chips to fish in rivers.

Plant resources were also widely used. They gathered roots, berries, and native vegetables in prairies, forests, and marshes. Berries, especially blackberries, were dried and made into cakes for dessert or later use. Flour and potatoes were added to their diet through trade with settlers.

The Snohomish raised native Salish Wool Dogs (sqix̌aʔ). They sheared the dogs for their valuable wool. The wool was made into clothing and blankets. The Snohomish were known for their woolly-dog crafts among the Coast Salish. They also made blankets from feathers, fireweed, and high-quality mountain goat wool from the Cascade Mountains.

Trade and Travel

The Snohomish were important in trading mountain goat wool and dog wool. They traded with many coastal groups who did not have access to these resources. The Snohomish sold large amounts of mountain goat wool and blankets to the Indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island.

A common type of money used by the Snohomish was shell money, called dentalium or solax. While many tribes traded for shells, the Snohomish could gather some types in their own land. However, certain shells still had to be traded for. Shells were strung together on a string. Some high-class people wore shells as jewelry, like on necklaces or as earrings.

The canoe was the main way to travel long ago. Even today, canoes are important for cultural events. The Snohomish traditionally used five types of canoes. The largest was the Quinault-style canoe. This was an ocean-going canoe made by the Quinault people, who traded it to the Snohomish. It could carry up to 60 people.

The smaller Nootka-style canoe (ʔəʔutx̌s) was also called a war canoe or Chinook canoe. It was a saltwater canoe originally from the Makah people. The Snohomish used it widely for travel. They painted this canoe black outside and red inside. It could carry up to fifteen people. A smaller version, the stiwatɬ, was made for women and for carrying trade goods. The Nootka-style canoe replaced a similar canoe, the qəbuɬ, which the Snohomish made themselves.

For river travel, the Snohomish used two types of canoes. The river canoe (sdəxʷiɬ) was the smallest. It was usually built for two people and used for duck hunting and fishing. The more common shovel-nose canoe (ƛ̕əlayʔ) was widely used for quick river travel and fishing.

Traditional Clothing and Appearance

In summer, Snohomish men usually wore long pants made of buckskin. They had belts made of buckskin or otter skin. Men wore shirts with or without sleeves, often trimmed with otter skin. Women wore long skirts made of cedar bark and long-sleeved buckskin shirts. Women also used cedar-bark capes to stay dry in the rain. Both men and women wore capes made of bearskin or sealskin, fastened with bone or yew pins. They wore moccasins or went barefoot. Both men and women wore cedar basket hats with buckskin chin straps. In winter, men wore warm raccoon-skin hats with fur.

Snohomish women parted their hair in the middle. It hung loose on each side, covering the ear, and was braided below the ear. Men parted their hair in the middle and tied it in a knot at the neck. When working or fighting, men tied their hair in a bun on top of their head. This bun was decorated with shell money. High-class men decorated their hair for ceremonies. They braided otter skin into their hair and painted it red. Very young children wore their hair loose. A slave's hair was cut short.

Both men and women painted their faces with red paint. This helped prevent chapping and kept their skin cool in summer. Sometimes, paint was used to create designs that showed a person's spirit powers. Women also tattooed their arms and legs, but this had no religious meaning.

Snohomish Society

How Society Was Organized

The village was the highest level of daily political organization. The extended family was very important in traditional Snohomish society. An extended family included several related families living in the same house. Each family had its own section. Some large houses held many extended families. Families formed a complex network of friendships through marriage. This helped them get hunting, fishing, and gathering rights in good locations.

Like other Puget Sound tribes, the Snohomish did not traditionally have "chiefs." Instead, there were high-ranking nobles who helped guide village matters and settle disagreements. But they did not have total power over everyone. For specific activities, like hunting or war parties, special leaders could be chosen. These leaders had more power during that activity. War leaders had great power over warriors. But they still listened to advice from other high-ranking people.

For laws and justice, groups sent speakers who decided on fair payments to settle arguments. An unsettled argument could lead to war. A common way to show friendship after a dispute was for two tribes to cut up blankets together. Then, they would weave the other tribe's blanket wool into their own blankets.

After Europeans arrived, Snohomish society started to change. A system developed where one chief at hibulb led all the Snohomish villages. This chief worked with various sub-chiefs. This role was usually passed down through families. But the chief did not have absolute power. Decisions were made by a majority vote at council meetings. William Shelton was one such chief. He was the last hereditary chief of the Snohomish before the system of hereditary chiefs ended.

Today, the Snohomish are part of the Tulalip Tribes. The Tulalip Tribes have their own government system.

Traditionally, Snohomish society had three classes: high-class (siʔab), low-class (p̓aƛ̕aƛ̕), and slaves (studəq). Slaves were prisoners of war. They could not legally gain their freedom on their own. But it was possible (though rare) for a slave's children to become free through a good marriage. Otherwise, the children of a slave were also slaves. Sometimes, a slave's family might buy their freedom if they could afford it. Enslaved children took part in religious life like other children. Those who gained powerful spirit powers as they grew up were respected and treated as equals by their masters.

Potlatch Ceremonies

Potlatches (sgʷigʷi) are large gatherings that have been held by the Snohomish and other Coast Salish people for a long time. The potlatch was the basis of their economy before colonization. Today, it is still a very important part of Snohomish culture. Traditional potlatches were feasts where gifts were given.

Potlatches were held for many reasons. These included naming ceremonies, funerals, after a successful hunt, for a marriage, to settle a debt or argument, or to celebrate a salmon run. Holding a grand potlatch by giving away almost all of one's belongings was highly respected. It made a person very famous. Potlatches helped strengthen friendships and connections with nearby peoples. They also brought unity among the different Snohomish villages.

The main potlatch houses for the Snohomish were at hibulb, səxʷtəqad, dəgʷasx̌, and č̓əč̓ɬqs. Other villages also had potlatch houses. It is thought there were more potlatch houses before the population dropped due to smallpox.

A traditional potlatch usually invited hundreds of people from local and distant villages. There was a long welcome ceremony. Each arriving group had its own day for welcome. When they arrived, they were greeted with a dance. The arriving group would respond with a song. After all the welcome ceremonies, there would be feasting, dancing, and singing. Giving out gifts (potlatching) was common, but it did not happen at every potlatch. Potlatches also included long speeches by famous speakers, who received gifts for their speeches. People showed their spirit powers by singing power songs or doing tricks.

Yearly Cycle of Activities

Even though the Snohomish had permanent homes, they moved around for part of the year. Their traditional life involved a year-long cycle of hunting, fishing, and gathering. They did this all across their land and beyond. Some people, especially the sick and elderly, stayed in their villages all year. But most people took part in the seasonal gathering cycle. The fact that different Snohomish villages participated in the same yearly cycle in the same areas helped unite them.

The cycle began in spring. People started gathering salmonberries in the lowlands of the Cascades. By summer, people traveled widely to hunt, fish, gather berries, dig clams, and collect other items along the islands and coast. Some also traveled to Stevens Pass to gather berries later in the summer. Around August, people went inland to hunt elk and get ready for the salmon runs. In early fall, salmon began running through Snohomish territory. Upriver fishing started. Hunters also focused on deer, bear, beaver, and other animals. In late fall, as people returned to their villages for winter, they traveled far upriver into Skykomish territory to hunt mountain goats in the Cascades. Winter was a time for religious ceremonies, crafts, and building. Steelhead fishing took place in January.

In more recent times, as more people worked in hop fields, the summer months became a time for traveling to the fields for work. Then they would head home for the winter.

Snohomish Language

The Snohomish language is Lushootseed. This is a Coast Salish language spoken by many different groups around Puget Sound. Lushootseed has two main dialects: Northern and Southern. Each is divided into smaller subdialects. The Snohomish dialect (also called the Tulalip dialect) is a subdialect of Northern Lushootseed. It has features of both Northern and Southern Lushootseed because of its location.

Fewer people speak Lushootseed today, with most speaking English. But the Tulalip Tribes are working to bring the language back into daily use. They also promote traditional cultural knowledge called x̌əč̓usadad. The Tribes offer Lushootseed language classes in local schools. They have also held Catholic Mass in the language.

Modern Snohomish Tribes

Tulalip Tribes of Washington

Most Snohomish people are now members of the officially recognized Tulalip Tribes of Washington. The Tulalip Tribes represent several groups. These include the Snohomish, Skykomish, and Snoqualmie. The Snoqualmie are also represented by the Snoqualmie Indian Tribe. This tribe successfully fought for its own official recognition.

The Tulalip Tribes run two casinos: Quil Ceda Creek Casino and the Tulalip Resort Casino. They also manage the only tribal town in the country, Quil Ceda Village (Lushootseed: qʷəl̕sidəʔ ʔalʔaltəd). The Tribes operate the Hibulb Cultural Center, which is a cultural center and museum. They also have several schools within the Marysville School District. They offer a Montessori school and programs for early childhood education and other services for children and adults. In 2006, the Tribes employed 2,400 people.

Each year, the Tulalip Tribes take part in the Tribal Canoe Journeys. This is a cultural event for tribes across Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. In 2003, the Tulalip Tribes hosted the event. They celebrate Treaty Day around January 22. They also hold powwows and traditional celebrations throughout the year. The Tulalip Tribes also have facilities for the Smokehouse religion.

The Tulalip Reservation is west of Marysville. It was created for the Snohomish and other groups by the Treaty of Point Elliott. It is located on traditional Snohomish land. However, most members today live off the reservation.

Snohomish Tribe of Indians

Some Snohomish people are members of the Snohomish Tribe of Indians. This group is not officially recognized by the government. They say they are descended from five original groups: the Snohomish, Sdodohobsh, N'Quentlmamish, Skykomish, and Sktalejum. The group was formed in 1974. They have tried to get official recognition and a reservation between Snohomish and Monroe. In 2004, their request for recognition was denied. They appealed this decision in 2008. They hold an annual powwow on Marrowstone Island. In 2008, the group had about 1,200 members. It is not known what percentage are of Snohomish descent.

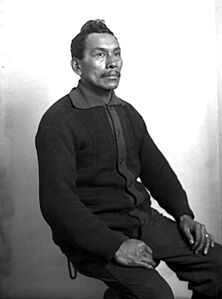

Famous Snohomish People

- Boeda Strand, a basket weaver

- William Shelton, a chief

- Tommy Yarr, a former NFL player and Notre Dame Fighting Irish football captain

See also

In Spanish: Snohomish (tribu) para niños

In Spanish: Snohomish (tribu) para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |