Duwamish people facts for kids

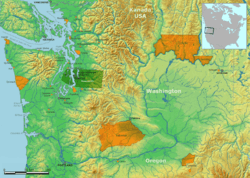

Duwamish territory shown highlighted in green. Orange blocks are modern Indian reservations.

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| About 253 (1854); about 400 enrolled members (1991), about 500 (2004). |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Metropolitan Seattle, Washington | |

| Languages | |

| Southern Lushootseed, English | |

| Religion | |

| Many Indigenous or Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Suquamish, Sammamish, Snoqualmie; ancestral Dxʷ'Dəw?Abš, "the People of the Inside", and Xacuabš "the People of the Large Lake" (before mid-1850s). Coast Salish |

The Duwamish (pronounced Dxʷdəwʔabš) are a group of Native American people. They speak a language called Lushootseed. The Duwamish have lived in what is now Seattle, Washington, for a very long time. They have been there since the end of the last Ice Age, about 10,000 years ago.

The Duwamish Tribe comes from two main groups. These were the "People of the Inside" (who lived near Elliott Bay) and the "People of the Large Lake" (who lived near Lake Washington). Over time, their culture has continued to grow and change. Today, some Duwamish people are also part of the Tulalip Tribes or the Muckleshoot Tribe.

The modern Duwamish Tribe formed around the time of the Treaty of Point Elliott in the 1850s. The U.S. government does not officially recognize them as a tribe. However, the Duwamish are still an organized tribe. In 2004, they had about 500 members. In 2009, the Duwamish Tribe opened their own Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center. It is located in West Seattle, near an old village site called Ha-AH-Poos.

Contents

The Duwamish Tribe: A Rich History

Life Before European Settlers Arrived

The area that is now Seattle has been home to people for about 10,000 years. Places like West Point in Discovery Park show signs of life from at least 4,000 years ago. Villages near the mouth of the Duwamish River have been lived in since the 500s AD.

There were 13 important villages in what is now Seattle. The people living around Elliott Bay and the Black and Cedar Rivers were called the doo-AHBSH. This name means "People of the Inside." They had four main villages on Elliott Bay. This area had many rich tidelands, full of seafood.

People living around Lake Washington were known as the hah-choo-AHBSH. This means "People of the Large Lake." Another group, the Ha-achu-abshs, lived around Lake Union. They were called "People of the Small Lake." These groups saw themselves as separate from the People of the Inside. Today, they are all part of the Duwamish Tribe. Before the Lake Washington Ship Canal was built, Lake Washington flowed into the Black River. This river then joined the Cedar and White (now Green) rivers to form the Duwamish River. As more Europeans arrived, the People of the Large Lake and the People of the Inside came together as the Duwamish Tribe.

Seasonal Living and Resources

Many villages existed in the Seattle area and the Snoqualmie River valley. Like other Coast Salish people, the Duwamish moved with the seasons. They spread out in spring, gathered for salmon in summer, and spent winters in large longhouses.

In spring, they gathered salmonberry shoots and bracken fern fiddleheads. Hunters looked for deer or elk in grasslands. Camas plants were gathered or traded from nearby prairies. These grasslands also provided berries, roots, and other useful plants. Garry oak trees, found in places like Seward Park, might have been planted for their edible acorns.

In summer and fall, they picked many kinds of berries. These included thimbleberries, salal, raspberries, and blackberries. Berries were eaten fresh or dried into cakes for winter. Dried fish and oil were mixed to make pemmican, a good travel food. Women and children gathered wetland plants like cattails for mats and wapato (Indian potatoes) for food. Crayfish and freshwater mussels were found in the lake.

Shellfish were available all year. From midsummer to November, life focused on salmon. Salmon returned to almost every stream. They were dried on racks to save them for winter.

During the long, wet winter, people ate dried fish and berries. They also hunted ducks, beaver, muskrat, raccoon, otter, and bear. Winters were a time for building, repairs, art, and social events. They also shared stories from their rich oral traditions.

Life was not always easy. Northern tribes sometimes raided their lands. Food could be scarce. A large trade network helped share resources when needed. This network worked well until new challenges arrived.

Community and Social Structure

Not much information exists about the Duwamish ancestors before the 1850s. What we know comes from descriptions from the mid-1800s. Changes began happening quickly after 1833.

Each village had one or more cedar plank longhouses. These large homes held many family members, sometimes tens of people. Today, some buildings in Seattle look like traditional longhouses. Ivar Haglund's Salmon House Restaurant by Lake Union is one example. The Burke Museum at the University of Washington also has a longhouse-like design. The Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center, opened in 2009, also looks like a traditional longhouse.

Villages were usually built facing a beach or river. They were near a creek for drinking water. Most land was heavily forested. Travel by canoe was much easier than by land.

The People of the Inside and the People of the Large Lake were not a single nation. They were a group of villages connected by language and family. Relationships within families and the community were very important.

These groups, along with the People of the Small Lake, the People of Lake Sammamish, and the People of the Snoqualmie, were all closely related. The Suquamish were also related. The Duwamish, living in a busy area, were among the first to lose their lands when Europeans settled.

Trading was common across the entire Pacific Northwest. Relationships and trade were often made stronger through marriage between different groups. Wives usually moved to their husband's village. While each family village had its own customs, they shared a language, beliefs, and ceremonies.

The central and southern Puget Sound was a main waterway for the Lushootseed Coast Salish Nations. There was so much food that these people had one of the few settled hunter-gatherer societies in the world. Their lives revolved around family groups in villages and sharing with other villages.

Society had three main groups: upper class, lower class, and slaves. These were mostly passed down through families. High status came from good family history, connections with other tribes, smart use of resources, and special knowledge about spirits. This combined social, religious, and economic power. Like some other Native American groups, Duwamish mothers shaped their babies' heads to create a sloping forehead. Traditionally, there was no single, permanent political leader. This confused European settlers.

European Contact and Big Changes

From the 1800s, the fur trade in the Puget Sound area brought fast changes. White settlements were set up at Alki in 1851 and Pioneer Square in 1852.

By the time the Coast Salish people understood how much things were changing, it was late. After only five years, their lands were taken. The Treaty of Point Elliott was signed in 1855. There are questions about if this treaty was fair. The two sides did not understand each other. The U.S. government and its agents had their own goals. White settlers chose leaders they liked, ignoring the Native ways of leadership. Many traditional customs were stopped.

Important Duwamish People During Contact

Chief Seattle (born around 1784, died 1866) is the most famous Duwamish leader. His mother was from the People of the Inside, and his father was a high-status man of the Suquamish. Chief Seattle became a leader of his people, from the time they were the People of the Inside and the People of the Large Lake, to when they became known as the Duwamish Tribe. He had two wives and seven children. His daughter, Princess Angeline, is also well-known.

Besides Chief Seattle, Lake John Cheshiahud and his family are some of the few Duwamish people from the late 1800s that we know about. He was also called Chudups John. He was one of the few Duwamish who did not move to the Port Madison Reservation. He and his family lived on Portage Bay, part of Seattle's Lake Union, in the 1880s. He had a cabin and a potato patch there.

Chudups John and his family, like Princess Angeline, were allowed to stay in Seattle. Most Native people were not allowed to live in Seattle after the mid-1860s. In 1927, his daughter Jennie provided a list of villages along Lake Washington. This list is a key source of information about where these villages were.

Hwehlchtid, known as "Salmon Bay Charlie," lived in a village called shill-SHOHL on the southern shore of Salmon Bay. He did not want to leave his home. Charlie and his wife Chilohleet'sa stayed in their homeland long after others moved away. Around 1905, photographers took pictures of Salmon Bay Charlie's house and canoe.

The Treaty of Point Elliott

The Treaty of Point Elliott was signed on January 22, 1855, in Mukilteo, Washington. It was approved in 1859. Leaders from the Duwamish, Suquamish, Snoqualmie, Snohomish, Lummi, Skagit, Swinomish, and other tribes signed it. The Duwamish leaders who signed were Chief Seattle, Ts'huahntl, Now-a-chais, and Ha-seh-doo-an.

The treaty promised fishing rights and reservations. It created the Port Madison, Tulalip, Swinomish, and Lummi reservations. However, no reservations were set up for the Duwamish, Skagit, Snohomish, or Snoqualmie.

Coast Salish people did not have permanent political leaders like Europeans. Because of this, Governor Isaac Stevens appointed chiefs to help with his plans. The treaty was also complicated by the different ways the two sides understood things.

The treaty included a very important rule about fishing rights: "The right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory."

Governor Stevens had several goals for the treaty. He wanted to gather Native people onto a few reservations. He wanted them to farm and adopt European ways. He planned to pay for their lands with blankets, clothing, and useful items over many years, not money. He also wanted to provide schools, teachers, and tools. He aimed to stop wars and slavery among them. He also wanted to limit alcohol use. He said they could keep fishing and hunting on unoccupied land as long as it was empty. He also planned to divide reservation lands among families in the future. These goals were very different from what was said during the talks. Native Nations relied on spoken agreements.

After the Treaty Was Signed

The U.S. government did not keep its promises to the Duwamish. The Duwamish never received a reservation. A plan for a reservation was blocked in 1866. Some Duwamish joined other tribes and moved to reservations. Many went to the Port Madison Reservation, and some to Tulalip or Muckleshoot. But many refused to leave their traditional homes. The Duwamish people in Seattle were among those who did not want to move.

In the mid-1860s, a plan was made for a Duwamish reservation along the White and Green River Valleys. But in 1866, many settlers in King County signed a petition against it. Important Seattle leaders like Arthur Denny and David Denny signed this petition. The plan for the reservation was then dropped.

By 1910, visible Native presence in Seattle had mostly disappeared. This was due to city rules and repeated fires.

Duwamish Tribal Status Today

The Duwamish Tribe created a constitution and rules in 1925. However, the United States federal government does not officially recognize them as a tribe. Individually, Duwamish people are recognized as Native Americans by the BIA. But the tribe as a whole is not.

To become a member of the Duwamish Tribe, a person must show their family history. Not all Duwamish people are members of the tribe today. This is because family records were not always kept well. The tribe's website states they had over 600 members in 2018.

The Duwamish were part of land claims against the government in the 1930s and 1950s. After the Boldt Decision in 1974, they tried to be included under the Treaty of Point Elliott. In 1977, they asked for federal recognition.

To be recognized, the Duwamish Tribe must prove they have been an organized tribe since 1855. In 1979, Judge George Boldt said the tribe had not existed continuously. He pointed to a gap in records from 1915 to 1925. Because of this, they were not given treaty fishing rights.

Later, an attorney for another tribe said Judge Boldt's decision was based on incomplete information. This suggests the decision could be appealed. In the mid-1980s, the BIA said that since the Duwamish had no land, they could not be recognized as a tribe.

In 1988, 72 descendants of Washington settlers supported the Duwamish Tribe's request for recognition. These were members of the Pioneer Association of the State of Washington.

In the 1990s, there were attempts in Congress to stop unrecognized tribes from seeking recognition. These attempts failed. Whether a tribe gets recognized often depends on the mood of Congress.

The BIA denied recognition in 1996. The Tribe then gathered more proof of their existence. They found evidence in church records, news reports, and oral histories. This new evidence led the BIA to change its decision. The Tribe briefly won federal recognition in 2001. But the ruling was canceled in 2002 due to procedural errors.

The Tulalip and Muckleshoot tribes have opposed recognition for local unrecognized tribes. They say they are the rightful heirs of these groups. Despite this, the Duwamish Tribe has continued to fight for recognition in court. In 2013, a judge ordered the Department of Interior to reconsider their denial. In 2015, the BIA again said the Duwamish did not meet the criteria. In 2022, the Duwamish sued the Department of Interior again to gain federal recognition.

Recent Duwamish History

Unlike many other Native groups, many Duwamish did not move to reservations. They have worked to keep their cultural heritage alive. In recent years, elders and younger members are helping to bring back and develop this heritage.

Duwamish members are active in Seattle's Native American community. They are involved in groups like United Indians of All Tribes and the Seattle Indian Health Board.

In 1970, local Native Americans became very visible. Leaders like Bob Satiacum and Bernie Whitebear occupied Fort Lawton. This land was originally Native land. They argued that under the Treaty of Point Elliott, they had a claim to any extra land. After long talks, this led to the creation of the Daybreak Star Cultural Center in 1977. This center became a base for Native Americans in Seattle.

Cecile Hansen, a great-great-grandniece of Chief Sealth, has been the elected leader of the Duwamish Tribe since 1975. She also helped start Duwamish Tribal Services in 1983. This group provides social and cultural services to the Duwamish community. Hansen has also worked hard to gain treaty rights for the Duwamish.

James Rasmussen of the Duwamish Tribe has led efforts to restore the Duwamish River since 1980. He works with citizen groups and tribe members. They helped get the lower five miles of the river declared a Superfund Site. This means it is a very polluted area that needs cleaning. The most polluted spots are being cleaned up. This work continues with citizen groups and the port.

James Rasmussen said, "These salmon and critters here are my brothers and my cousins. I care about them that much. And our ancestors are still here. They see what's going on, and they hold you responsible."

To celebrate their identity and heritage, the Duwamish built the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center. It is on land they bought near an old village site called yee-LEH-khood. The center is built along Marginal Way SW.

The Renton History Museum in Renton, Washington, has a small exhibit about the Duwamish Tribe's history and culture.

Understanding Duwamish Names

Names have changed over time since Europeans arrived.

The name Duwamish comes from Dxʷ'Dəw?Abš. This means "the People of the Inside" or "the People Inside the Bay." This name also includes the historic "People of the Large Lake" (Xacuabš).

The Duwamish River also got its name from the Duwamish people. The People of the Inside called the river Dxʷdəw. This name comes from a word meaning "inside something relatively small," referring to Elliott Bay.

The city name Seattle also comes from the Lushootseed language. The famous Duwamish leader is known as Chief Seattle. His name was si'áb Si'ahl, meaning "high status man Si'ahl." His gravestone shows his baptized name: Noah Sealth. The name Seattle for the city dates back to 1853. It is said that David Swinson 'Doc' Maynard named the city.

The Duwamish language, Southern Lushootseed, is part of the Salishan family. The Lushootseed pronunciation of the Duwamish Tribe's people is [dxʷdɐwʔabʃ]. English does not have all the same sounds as Lushootseed.

See also

In Spanish: Duwamish (tribu) para niños

In Spanish: Duwamish (tribu) para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |