United States v. Washington facts for kids

Quick facts for kids United States v. Washington |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Court | United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit |

| Full case name |

Full name

United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellee, Quinault Tribe of Indians, et al., Intervenors-Plaintiffs, v. State of Washington, Defendant-Appellant, Thor C. Tollefson, Director, Washington State Department of Fisheries, et al., Intervenors-Defendants, Northwest Steelheaders Council of Trout Unlimited and Gary Ellis, Intervenor-Defendant-Appellant. United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellee, Quinault Tribe of Indians, et al., Intervenors-Plaintiffs, v. State of Washington, Defendant, Thor C. Tollefson, Director, Washington State Department of Fisheries, et al., Intervenors-Defendants, Washington Reef Net Owners Association, Intervenor-Defendant-Appellant. United States of America, Plaintiff, Quinault Tribe of Indians, et al., Intervenors-Plaintiffs, Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, Squaxin Island Tribe of Indians, Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, Skokomish Indian Tribe, Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians, Quinault Tribe of Indians, on its own behalf and on behalf of the Queets Band of Indians, Makah Indian Tribe, Lummi Indian Tribe, Hoh Tribe of Indians, Confederated Tribes And Bands of The Yakima Indian Nation, Upper Skagit River Tribe, And Quileute Indian Tribe, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. State of Washington, Defendant-Appellee, Thor C. Tollefson, Etc. et al., Intervenors-Defendants. United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellee, Quinault Tribe of Indians, et al., Intervenors-Plaintiffs, v. State of Washington, Defendant-Appellant, Thor C. Tollefson, Director, Washington State Department of Fisheries, et al., Intervenors-Defendants, Carl Crouse, Director of The Department of Game, The Washington State Game Commission, Intervenors-Defendants-Appellants. United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellee, Quinault Tribe of Indians, et al., Intervenors-Plaintiffs, v. State of Washington, Defendant-Appellant, Thor C. Tollefson, Director, Washington State Department of Fisheries, et al., Intervenors-Defendants, Thor C. Tollefson, Director, Washington State Department of Fisheries, Intervenor-Defendant-Appellant. United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellee, Quinault Tribe of Indians, et al., Plaintiffs, v. State of Washington, Defendant, Thor C. Tollefson, Director, Washington State Department of Fisheries, et al., Defendants, Washington Reef Net Owners Association, Defendant-Appellant. United States of America, Plaintiff, Quinault Tribe of Indians, et al., Plaintiffs, Puyallup Tribe of Puyallup Reservation, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. State of Washington, Defendant-Appellee, Thor C. Tollefson, Director, Washington State Department of Fisheries, et al., Defendants. United States of America, Plaintiff, Quinault Tribe of Indians, et al., Plaintiffs, Nisqually Indian Community of The Nisqually Reservation, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. State of Washington, Defendant-Appellee, Thor C. Tollefson, Director, Washington State Department of Fisheries, et al., Defendants

|

| Decided | June 4, 1975 |

| Citation(s) | 520 F.2d 676 |

| Case history | |

| Prior history | 384 F. Supp. 312 (W.D. Wash. 1974) |

| Subsequent history | Cert. denied, 423 U.S. 1086 (1976). |

| Holding | |

| "[The] state could regulate fishing rights guaranteed to the Indians only to the extent necessary to preserve a particular species in a particular run; that trial court did not abuse its discretion in apportioning the opportunity to catch fish between whites and Indians on a 50-50 basis; that trial court properly excluded Indians' catch on their reservations from apportionment; and that certain tribes were properly recognized as descendants of treaty signatories and thus entitled to rights under the treaties. [Affirmed and remanded]." | |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Herbert Choy, Alfred Goodwin, and District Judge James M. Burns (sitting by designation) |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Choy |

| Concurrence | Burns |

United States v. Washington is a very important legal case from 1974. It is often called the Boldt Decision after Judge George Hugo Boldt, who made the first ruling. This case was about the fishing rights of Native American tribes in the state of Washington.

The decision confirmed that tribes had the right to co-manage and catch salmon and other fish. These rights came from old treaties signed with the U.S. government. The tribes had given up their land but kept their right to fish in their traditional spots, even outside their reservations.

Over time, the State of Washington tried to limit these treaty rights. This happened even though the state had lost earlier court cases on the issue. Those cases had already said that Native peoples could reach their fishing spots through private land. They also said the state could not charge tribes a fee to fish or treat them unfairly in how they fished.

The Boldt Decision went further. It said that tribes were allowed to catch half of all the fish harvested each year. In 1975, a higher court, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, agreed with Judge Boldt. The U.S. Supreme Court chose not to hear the case, meaning Boldt's ruling stood.

When the state did not enforce the court's order, Judge Boldt asked federal agencies like the United States Coast Guard to help. In 1979, the Supreme Court again supported Judge Boldt's ruling. Justice John Paul Stevens wrote that "Both sides have a right, secured by treaty, to take a fair share of the available fish."

Contents

- Understanding the Boldt Decision: Why it Matters

- The Boldt Decision in District Court

- The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Reviews the Decision

- What Happened After the Boldt Decision?

- Images for kids

Understanding the Boldt Decision: Why it Matters

How Native American Tribes Fished in the Past

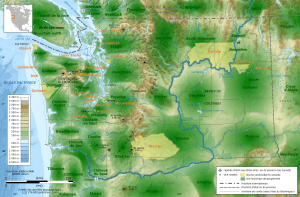

Native American tribes in the Pacific Northwest relied heavily on salmon. This resource helped them become some of the richest tribes in North America. People estimated that tribes in the Columbia River basin caught about 43 million pounds of salmon every year. This was enough for their own needs and for trading with others. By the 1840s, tribes traded salmon with the Hudson's Bay Company. The company then shipped the fish to places like New York and Great Britain.

Treaties: Promises for Fishing Rights

In the 1850s, the U.S. government made several treaties with Native American tribes in the Pacific Northwest. For example, in the Treaty of Olympia, Governor Isaac Stevens agreed to protect tribal rights.

The treaty stated: "The right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations is secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary houses for the purpose of curing the same; together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horses on all open and unclaimed lands."

Other treaties, like those of Medicine Creek, Point Elliott, Neah Bay, and Point No Point, had similar language. They all protected the tribes' right to fish outside their reservations. The tribes agreed to give up their land but insisted on keeping their fishing rights across the Washington Territory.

What Happened After the Treaties Were Signed?

At first, the U.S. government honored these treaties. But as more white settlers moved into the area, they started to interfere with the tribes' fishing rights. By 1883, settlers had built over forty salmon canneries. By 1905, there were twenty-four canneries in the Puget Sound area.

Settlers also began using new fishing methods. These methods stopped many salmon from reaching tribal fishing areas. When Washington became a state in 1889, it passed laws that limited tribal fishing. Some people believed these laws were meant to protect white fisheries. By 1897, the state banned the use of weirs, which Native fishermen traditionally used. Because of these changes, the tribes went to court to protect their treaty rights.

Early Court Cases Protecting Fishing Rights

In 1887, in a case called United States v. Taylor, members of the Yakama tribe sued to get access to their fishing spots. A non-Native settler, Frank Taylor, had fenced off land, blocking the Yakama. The court eventually ruled that the tribe had kept its fishing rights. This meant their right to fish stayed with the land, even when Taylor bought it.

United States v. Winans: Protecting Access to Fishing Spots

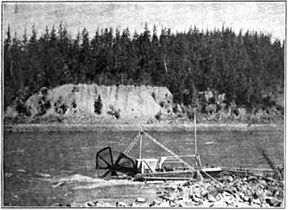

Another important case, United States v. Winans, came up ten years later. It involved fishing rights at Celilo Falls, a traditional Native fishing spot. Two brothers, Lineas and Audubon Winans, owned land near the Columbia River. They used fish wheels, which caught many salmon and prevented them from reaching tribal areas. The Winans also stopped anyone from crossing their land to get to the falls.

The U.S. government sued to protect the tribe's treaty rights. In 1905, the Supreme Court ruled that the tribe had kept its fishing rights when they gave up their land. This meant the Winans could not stop the tribes from fishing there.

Tulee v. Washington: No Fees for Fishing

In Tulee v. Washington, the Supreme Court again ruled on the Yakama tribe's treaty rights. In 1939, Sampson Tulee, a Yakama man, was stopped for fishing without a state license. The Supreme Court said that the state could not charge the Yakama a fee for fishing.

Puyallup Cases: Fair Fishing Rules

There were three Supreme Court cases involving the Puyallup tribe. In the first, Puyallup Tribe v. Department of Game of Washington (Puyallup I), the state had banned using nets to catch steelhead trout and salmon. The tribes kept using nets based on their treaty rights. The court said the state could make reasonable rules for fish conservation, but these rules could not be unfair to the tribes.

In the second case, Department of Game of Washington v. Puyallup Tribe (Puyallup II), the court found the state's rules were unfair. The state still banned nets for steelhead trout, which only Native people used. But hook and line fishing, used by non-Native people, was allowed. This meant all steelhead trout fishing went to sport anglers, not the tribes.

The third case, Puyallup Tribe, Inc. v. Department of Game of Washington (Puyallup III), happened in 1977. The court said the state could regulate fishing on the Puyallup Reservation if it was for conservation and fair to everyone.

In 1969, Judge Robert C. Belloni made an important ruling in Sohappy v. Smith. This case involved the Yakama tribe and the state of Oregon. Oregon had given most of the fish to sport and commercial fishermen, leaving almost nothing for the tribes. Judge Belloni said that the state could not put its own goals above the tribes' federal fishing rights. He ruled that the tribes were allowed a fair share of the fish harvest.

The Boldt Decision in District Court

Why the Case Was Brought to Court

Even after the Belloni decision, Oregon and Washington states continued to stop Native people for breaking state fishing laws that went against their treaty rights. So, in September 1970, the U.S. government sued the State of Washington. The lawsuit said Washington was violating the treaty rights of several tribes, including the Hoh, Makah, Muckleshoot, Nisqually, Puyallup, Quileute, and Skokomish. Later, other tribes like the Lummi, Quinault, Sauk-Suiattle, Squaxin Island, Stillaguamish, Upper Skagit, and Yakama joined the case.

The Trial and Evidence

The first part of the case took three years just to get ready for trial. During the trial, Judge Boldt heard from about 50 witnesses and looked at 350 pieces of evidence. The evidence showed that the state had closed many net fishing sites used by Native peoples. However, it allowed commercial net fishing in other areas for the same fish. At most, the tribes caught only about 2% of the total fish. The state could not show any harm caused by Native fishing. Both experts and tribal members shared their knowledge. Tribal members told oral histories about the treaties and fishing rights. Judge Boldt found the tribal witnesses and experts to be more believable and well-researched.

Judge Boldt's Ruling

The court decided that when tribes gave up millions of acres of land in Washington State in the 1850s, they kept their right to fish. Judge Boldt looked at the notes from the treaty talks. He found that the U.S. government meant for tribes and settlers to share the fish equally.

The court stated that "in common with" meant "sharing equally the opportunity to take fish." This meant that non-treaty fishermen could catch up to 50% of the fish, and treaty-right fishermen could catch up to the same percentage. Judge Boldt's formula gave tribes 43% of the Puget Sound harvest, which was 18% of the total statewide harvest. This ruling meant the state had to limit how many fish non-Native commercial fishermen could catch.

The court also said the state could make rules for Native fishing, but only to protect the fish population. To do this, the state had to show that conservation could not be achieved by regulating only non-Native people. The rules also could not be unfair to Native people and had to follow proper legal steps.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Reviews the Decision

The Court's Decision

After Judge Boldt's ruling, both sides appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Washington state argued that the district court could not change state fishing rules. The tribes argued that the state should not regulate their fishing at treaty locations at all.

Judge Herbert Choy wrote the main opinion for the court. He agreed with Judge Boldt's decision "in all respects." He clarified that Boldt's equal sharing of fish did not include fish caught by people from outside Washington state.

Judge Choy stressed that states cannot make rules that go against treaties between the U.S. and Native nations. He concluded that the treaties from the 1850s meant Washington's rules were invalid. Non-Native people had "only a limited right to fish at treaty places." Judge Choy also said that the tribes had a right to a fair share of fishing opportunities to protect their treaty rights. He noted that the district court had a lot of freedom in dividing these rights.

A Concurring Opinion: Criticizing State Officials

District Judge James M. Burns wrote a separate opinion agreeing with the main decision. He criticized Washington State officials for not cooperating in managing the state's fisheries. Judge Burns felt that Washington's resistance forced Judge Boldt to act like a "perpetual fishmaster." He said he was sad to see judges forced to manage natural resources like fisheries. Judge Burns ended by saying that Washington's duty to manage its natural resources should not be forgotten.

Supreme Court Declines to Hear the Case

After the Ninth Circuit's ruling, Washington state asked the Supreme Court of the United States to review the case. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case. This meant that the Ninth Circuit's decision, which upheld Judge Boldt's ruling, remained the final word. Even after these rulings, discussions about how to divide the fish continued in court for many years.

What Happened After the Boldt Decision?

Legal Challenges and Enforcement

Stopping Challenges to the Ruling

After Judge Boldt's decision, the Washington Department of Fisheries made new rules to follow it. However, some fishing groups sued in state court to stop these new rules. The Washington Supreme Court supported these private groups. The U.S. Supreme Court then stepped in.

Justice John Paul Stevens announced the Supreme Court's decision. It upheld Judge Boldt's order and overturned the state court rulings. Stevens clearly stated that Boldt had the power to issue his orders. He said the federal court could even take over local enforcement if needed to fix violations of federal law.

Federal Oversight of Fishing

When the state would not enforce his order to reduce the catch of non-Native commercial fishermen, Judge Boldt took direct action. He put the fishing management under federal supervision. The United States Coast Guard and the National Marine Fisheries Service were ordered to enforce the ruling. They sent boats to confront those breaking the rules. Some protesters crashed into Coast Guard boats, and one Coast Guard member was shot. People caught breaking the court's orders faced penalties in federal court, and the illegal protest fishing stopped. The U.S. District Court continued to oversee the matter, identifying traditional fishing spots and issuing further orders.

Phase II: Habitat and Hatchery Fish

The case continued with new issues brought before the court in what was called "Phase II." Judge William H. Orrick, Jr. heard arguments about fish habitat. He ordered the State of Washington not to harm fish habitats. He also included fish raised in hatcheries in the allocation for Native people. The state appealed this decision. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals mostly agreed, keeping hatchery fish in the allocation but leaving the habitat issue open for further discussion.

Culvert Case: Protecting Fish Migration

In 2001, 21 tribes in northwestern Washington, along with the U.S. government, asked the court to rule on another issue. They wanted the court to say that the state had a duty under the treaties to protect fish runs and habitat. This was to ensure tribes could make a "moderate living." They also wanted the state to fix or replace culverts (tunnels under roads) that blocked salmon from migrating.

In 2007, the court ruled that Washington State had harmed salmon runs by building and maintaining culverts that blocked fish migration. This violated its treaty obligations. In 2013, the court ordered the state to greatly increase its efforts to remove state-owned culverts that block salmon and steelhead habitat. The state was told to replace the worst culverts by 2030.

Washington State appealed this decision. In 2016, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the district court's decision and the order. Washington State estimates it will need to fix 30 to 40 culverts each year to follow the court's order.

How Tribes Benefited from the Decision

The tribes involved gained a lot from the Boldt Decision. Before Boldt's ruling, Native tribes caught less than 5% of the fish harvest. By 1984, they were catching 49%. Tribal members became successful commercial fishermen, even fishing in places like Alaska.

The tribes also became co-managers of the fisheries with the state. They hired fish biologists and staff to help with these duties. Based on the Neah Bay Treaty and the Boldt decision, the Makah tribe caught their first California gray whale in over 70 years in 1999. After some lawsuits, the tribe was allowed to catch up to five whales a year for the 2001 and 2002 seasons.

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |