Pacific Railroad Surveys facts for kids

The Pacific Railroad Surveys (1853–1855) were a series of important trips across the American West. Their goal was to find and map the best routes for a transcontinental railroad. This railroad would connect the eastern and western parts of North America. These expeditions included surveyors, scientists, and artists. They gathered a huge amount of information about the American West, covering about 400,000 square miles (1,000,000 km2).

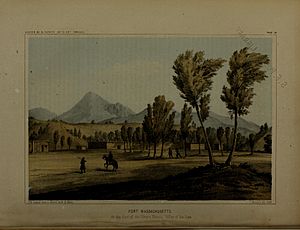

The reports from these surveys were published by the United States Department of War from 1855 to 1860. They contained valuable details about nature, including many pictures of animals like reptiles, birds, and mammals. Besides mapping railroad routes, the surveys also described the geology (rocks and land), zoology (animals), botany (plants), and paleontology (fossils) of the land. They also shared information about the Native Americans they met.

Contents

Why a Railroad? The Need for Connection

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, many Americans started moving west. This movement greatly shaped American history. At first, traveling by water was the easiest way to get around. But then, the steam engine was invented, which led to railroads.

By the 1830s, railroads became very popular in the eastern United States. People soon wanted to extend this new technology all the way to the western frontier.

Starting in the 1840s, the government sponsored several trips to find possible railroad routes across the West. However, it was hard to agree on one route. Different companies wanted the railroad to go through their areas for money. Also, cities and states competed to be the starting or ending point of the railroad.

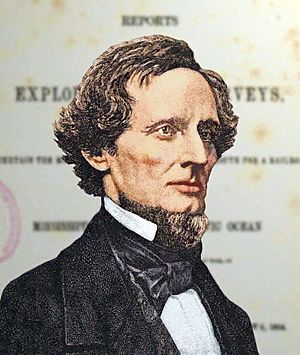

On March 3, 1853, Congress set aside $150,000 for the project. They asked Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to find "the Most Practical and Economical Route for a Railroad From the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean." Davis put Brevet Captain George B. McClellan and the Corps of Topographical Engineers in charge. This group was part of the U.S. Army. Their job was to "discover, open up, and make accessible the American West."

The biggest concern for the United States Congress was where to build the railroad. Many people tried to influence the decision because the railroad would bring big social, political, and economic changes. Building a transcontinental railroad would also be very expensive. Even the cheapest plans would cost as much as the entire federal budget for one year!

Despite these challenges, everyone agreed that a transcontinental railroad was urgently needed. In 1856, a report to Congress stated that building railroad and telegraph lines between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts was no longer a question. Everyone agreed it had to happen.

Exploring the West: Five Major Surveys

Five main surveys were carried out to find the best railroad routes.

- The Northern Pacific survey explored between 47 and 49 degrees north latitude. It went from St. Paul, Minnesota to the Puget Sound. Isaac Stevens, the new governor of the Washington Territory, led this survey. Captain George B. McClellan and Lt. Sylvester Mowry joined from the west. Lt. Rufus Saxton and Lt. Richard Arnold came from the east.

- The Central Pacific survey explored between 37 and 39 degrees north latitude. It went from St. Louis, Missouri to San Francisco, California. Lt. John W. Gunnison led this survey until he died in Utah. Lt. Edward Griffin Beckwith then took over. Others on this survey included Frederick W. von Egloffstein, George Stoneman, and Lt. Gouverneur K. Warren.

- There were two Southern Pacific surveys.

- One went along 35 degrees north latitude from Oklahoma to Los Angeles, California. This route was similar to parts of the later Santa Fe Railroad and Interstate 40. Lt. Amiel Weeks Whipple led this survey.

- The southernmost survey crossed Texas to San Diego, California. This route followed the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach trail. The Southern Pacific Railroad later completed its second transcontinental railway along this route in 1881. Lt. John Parke and John Pope led this survey.

- The fifth survey explored the Pacific coast. It went from San Diego to Seattle, Washington. Lt. Robert S. Williamson and Parke conducted this exploration.

From Maps to Tracks: Building the Railroad

The Pacific Railroad Surveys (1853–1855) gave a lot of useful information about possible routes. But this information alone wasn't enough to start building the railroad. Three other important things helped Congress make its final decision.

First, the California Gold Rush and the discovery of silver in Nevada caused a huge increase in the population of the West. More people meant a greater need for better transportation.

Second, the southern states left the Union at the start of the American Civil War. This meant southern politicians could no longer stop plans for a northern or central railroad route.

Third, more and more railroad experts were available. This gave Congress many good options for building the most efficient and affordable transcontinental railroad.

A railroad engineer named Theodore Judah was especially important. On January 1, 1857, he published "A practical plan for building The Pacific Railroad." In it, he explained a general plan and argued for a detailed survey of one specific route. This was different from the general surveys that had been done. After finding a good route over the Sierra Nevada mountains from Sacramento to Nevada in 1860, Judah found investors. He then started the Central Pacific Railroad in June 1861. In October 1861, Judah went to Washington D.C. to convince Congress to pass a law to help build the first transcontinental railroad along his route.

In 1862, Congress passed the Pacific Railway Act. This law created the Union Pacific Railroad Company. This company would build railroad and telegraph lines west from the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, Iowa. The Central Pacific Railroad would build lines east from Sacramento, California. On May 10, 1869, the two rail lines met. They joined with an honorary Golden Spike at Promontory Summit, Utah. Together, they had built 1,774 miles (2,855 km) of railroad track!

Exploring Nature: Plants and Animals

Important naturalists joined all the survey teams. Their job was to study the plants and animals found along the routes.

- Dr. James G. Cooper and Dr. George Suckley studied nature for the Northern Pacific route.

- Botanist Frederick Creutzfeldt joined the Central Pacific route survey. He died during the trip in Utah.

- Dr. Adolphus L. Heermann and Dr. Edward Hallowell went with Parke's Southern Pacific survey.

- Dr. Caleb B. R. Kennerly joined the Whipple expedition on the southern route.

- Heermann also went with Lt. Williamson on the trip up the West Coast from Fort Yuma to San Francisco.

Most of these naturalists also served as doctors for their teams. They were often experts in one or two areas of nature. Their main task was to collect and prepare plants and animals. These collections were then sent back east for more study. They collected everything: plants, mammals, fish, insects, birds, mollusks, snakes, lizards, and turtles. They collected both common and rare species.

Geologist William Phipps Blake explained this approach. He said they collected everything, whether it was new or already known. It was easier to remove extra items later than to try and find missing ones.

Plants and animals were preserved as well as possible in the camps. Then, they were shipped overland to the Smithsonian Institution and other expert centers for study. This journey often took months of rough travel, and not all collections survived. Heermann wrote about these difficulties. He had a good collection of reptiles, but the containers leaked. Without new alcohol, most of his reptile collection was lost.

Several naturalists wrote reports about their findings. These reports were included in the War Department's report to Congress. For example, Heermann wrote about birds, and Hallowell wrote about reptiles for Lt. Parke's expedition. Other leading naturalists also helped by describing the collections sent back from the trips. These included Asa Gray, Dr. John L. LeConte, William Cooper, Dr. Charles Girard, William G. Binney, and Dr. John S. Newberry.

One of the most important people was Spencer Fullerton Baird. He was the assistant secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Baird wrote several parts of the report to Congress. He was also responsible for many of the natural history illustrations. For example, bird skins collected by the teams were sent to him. He had artists at the Smithsonian create drawings of the birds as they would look in real life. These drawings were then colored by hand and included in the final report.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |