Asa Gray facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Asa Gray

|

|

|---|---|

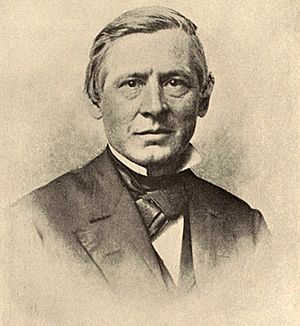

Asa Gray in the 1870s

|

|

| Born | November 18, 1810 |

| Died | January 30, 1888 (aged 77) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany |

| Institutions | University of Michigan Harvard University |

| Influences | Amos Eaton Charles Darwin |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | A.Gray |

Asa Gray (November 18, 1810 – January 30, 1888) is known as the most important American botanist of the 1800s. A botanist is a scientist who studies plants. Gray strongly believed that all members of a plant species are connected through their genes. He also supported the idea of evolution, which is how living things change over time.

Gray was a big supporter of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. He believed that evolution was guided by a Creator. His book Darwiniana helped explain that science and religion could work together.

For many years, Asa Gray was a professor of botany at Harvard University. He often visited and wrote to other top scientists, including Charles Darwin, who respected him greatly. Gray traveled to Europe to work with scientists there, and also explored the southern and western parts of the United States. He also created a large network of people who collected plant samples for him.

Gray wrote many books and articles. He helped organize all the known information about plants in North America. His most famous book was Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States, often called Gray's Manual. This book is still used today. Gray also studied why many plants in eastern Asia look very similar to plants in eastern North America. This is now called the "Asa Gray disjunction." Many places and plants are named after him.

In 1848, Gray became a member of the American Philosophical Society, a group that promotes useful knowledge.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Asa Gray was born in Sauquoit, New York, on November 18, 1810. His father, Moses Gray, was a tanner, which means he prepared animal hides to make leather. Asa was the oldest of eight children. His family later became farmers.

Even when he was young, Gray loved to read. He went to Clinton Grammar School and read many books from the library at Hamilton College. In 1825, he joined Fairfield Academy and later its medical college. It was during this time that he started collecting and preparing plant samples.

Gray tried to meet another famous botanist, John Torrey, in New York City. Torrey wasn't home, so Gray left his plant samples. Torrey was so impressed that he started writing letters to Gray. Gray earned his medical degree in 1831, but he never really practiced medicine because he loved botany more. He spent his time exploring New York and New Jersey to find plants.

In 1832, Gray taught chemistry, mineralogy, and botany in Utica, New York, and at Fairfield Medical School. He then became an assistant to John Torrey at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. Gray began exchanging plant samples and letters with botanists from all over the world.

Career as a Botanist

In 1836, Gray was chosen to be a botanist for the United States Exploring Expedition, also known as the "Wilkes Expedition." This was a big trip to explore different parts of the world. Gray helped plan for the expedition, but it had many problems and delays. He eventually left the expedition in 1838. Later, in 1848, he was hired to study the plant samples collected during the expedition.

On July 17, 1838, Gray became the first full-time botany professor at the new University of Michigan. He never actually taught classes there. Instead, the university sent him to Europe to buy books and equipment for their library and research. This trip also allowed him to study American plants in European collections.

Gray traveled to many cities in Europe, including Glasgow, London, Paris, Rome, Vienna, and Berlin. He met and worked with many important botanists, like William Jackson Hooker and Augustin Pyramus de Candolle. He bought about 3,700 books for the University of Michigan library. Even though he did great work, the university had money problems and asked him to resign in 1840.

While in Paris, Gray saw a dried plant sample that had no name. He named it Shortia galacifolia. For 38 years, he searched for this plant growing in the wild. Finally, in 1878, a collector found a sample and sent it to Gray, who was thrilled to confirm it was Shortia. Gray even led an expedition to the spot where it was found in 1879.

Harvard Professor

In 1842, Gray was offered a job as a professor at Harvard University. He would earn $1,000 a year and only had to teach botany, which gave him lots of time for research and working in Harvard's botanic garden. Gray accepted the job and started his duties in September 1842. He was known for his deep knowledge, especially in advanced classes, and for his excellent textbooks.

Gray moved into a house in the Botanic Garden in 1844, which is now called the Asa Gray House. As his work grew, he hired Isaac Sprague, a botanical illustrator, to help him with drawings for his books.

In 1848, Gray was hired to study the plant samples from the Wilkes Expedition. This included a year-long trip to Europe with his wife, Jane. They visited Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands. Gray worked at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in England, studying the plants.

In 1855, Gray made another quick trip to Europe. He read a new book called Géographie botanique raisonnée by Alphonse de Candolle. This book was important because it combined a lot of plant data to explain why plants grow in certain places. Gray realized this book would help organize the study of plants.

In 1858, Daniel Cady Eaton came to Harvard to study with Gray. Eaton later became a botany professor at Yale University. Gray was elected to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1859 and was one of the first 50 members of the National Academy of Sciences in 1863.

In 1864, Gray gave 200,000 plant samples and 2,200 books to Harvard. This led to the creation of Harvard's botany department and the Gray Herbarium, named after him. He also led the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Gray wrote many books, including Elements of Botany (1836), which taught that botany was useful for both medicine and farming. He also wrote high school textbooks like First Lessons in Botany (1857) and How Plants Grow (1858). These books were written to be easy for students and non-scientists to understand.

Gray worked closely with botanist George Engelmann. Gray supported the "natural system of classification" for plants, which looks at a plant's whole structure and where it grows. This was different from Linnaeus' system, which focused mainly on flower parts. Gray even named a plant genus, Suksdorfia, after a self-taught botanist named Wilhelm Nikolaus Suksdorf.

Gray was against slavery. He believed that science and Christianity showed that all people are connected. During the American Civil War, Gray strongly supported the North. He regretted not having children to send to the war. The war made it hard for him to get plant samples from the South.

After the war, Harvard got more money for its botany programs. Gray wanted to retire from teaching to focus on writing his book Flora of North America. In 1872, Charles Sprague Sargent became the director of the Botanic Garden, which freed up Gray's time. With financial support from others, Gray was finally able to resign from his professorship in 1873 and focus on his research and writing.

The "Asa Gray Disjunction"

Gray spent a lot of time studying a pattern now called the "Asa Gray disjunction." This is the surprising similarity between many plants found in eastern Asia and eastern North America. He thought that plants in eastern North America were more like those in Japan than those in western North America.

This pattern involves about 65 types of plants, and also includes fungi, arachnids, and insects. Scientists now believe these similarities might be due to similar environments, or because these plants were once spread out more widely and then changed over time. Gray's work on this topic greatly supported Darwin's theory of evolution.

Later Career

Even after retiring from teaching, Gray was still seen as the most important botanist in America. Many scientists relied on his knowledge. His home became the center for botany in America, with aspiring botanists coming to see him.

Gray focused on plant classification and gave lectures about Darwin's ideas. In 1883-1884, Liberty Hyde Bailey, who later became a famous botanist, worked as Gray's assistant. In 1887, Gray and his wife made their last trip to Europe.

Gray received several honorary degrees from universities like Harvard, Hamilton College, McGill University, and the University of Michigan.

Research in the American West

Before 1840, Gray's knowledge of plants in the American West was limited. He learned from other explorers like Edwin James and Thomas Nuttall. Later, he became close friends and colleagues with George Engelmann, a botanist who often explored the American West and Mexico. Engelmann would send plants to Gray, who would classify them.

Gray also worked with Ferdinand Lindheimer, who collected plants in Texas, and Charles Wright, who collected in Texas and New Mexico. These collaborations greatly increased what was known about plants in these areas.

Gray traveled to the American West twice, in 1872 and 1877, both times with his wife. His goal was to collect plant samples for Harvard. On his second trip with Joseph Dalton Hooker, they collected over 1,000 plant samples. Their research was published in 1880.

On both trips, Gray climbed Grays Peak in Colorado, a mountain named after him by another botanist, Charles Christopher Parry. His wife even climbed it with him in 1872. Gray named a new plant genus Plummera (now called Hymenoxys) after botanist Sara Plummer Lemmon.

Relationship with Darwin

Asa Gray met Charles Darwin in London in 1839. They shared a similar scientific approach and began writing letters to each other in 1855. They exchanged about 300 letters over the years. Darwin often asked Gray for information about American flowers, which helped him develop his theory of evolution. Gray, Darwin, and Joseph Dalton Hooker became lifelong friends.

Before 1846, Gray did not believe that species could change over time. But by the early 1850s, he understood that a species was a basic unit of classification, and that "like begat like" (meaning offspring are similar to their parents). This idea was very important for Darwin's theories. Gray also disagreed with the idea of "special creation" if it meant that evolution could not happen.

In 1858, Darwin's and Alfred Russel Wallace's papers on natural selection were read together at the Linnean Society of London. The reading included parts of a letter Darwin had sent to Asa Gray in 1857, which showed Darwin's ideas about the origin of species. This helped prove that Darwin had developed his theory earlier.

Darwin published his famous book, On the Origin of Species, in 1859. Gray received a copy and worked to protect the book from being copied without permission in America. He also helped Darwin get royalties (payments) from the American publisher. Darwin greatly valued Gray's friendship and support. He even dedicated his 1877 book, The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species, to Gray.

Gray was a Christian and a strong supporter of Darwin in America. He believed that God was the ultimate cause behind evolution. He wrote a book called Darwiniana (1876), which argued that Darwin's evolution and religious beliefs could exist together. Gray believed that nature showed clear signs of design and that God worked through natural processes.

In 1868, Gray visited Darwin in England. Darwin wrote that it was "absurd to doubt that a man may be an ardent theist & an evolutionist," thinking of Gray. Gray and his wife visited Darwin again in 1880, before Darwin died in 1882.

Personal Life

Asa Gray married Jane Lathrop Loring in May 1848. Her family was Unitarian, and Gray was a Presbyterian, but their different beliefs did not cause problems. They did not have children. Jane often went with her husband on his plant collecting trips. Gray was a very religious man and served as a deacon at his church in Cambridge.

In 1872, when his church moved to a new building, Gray planted two Kentucky yellowwood trees in front of it. These trees stood there until 2014.

Death

On November 28, 1887, Gray's hand and arm became paralyzed. He became speechless and quiet for two months. Asa Gray died on January 30, 1888. He was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery. His gravestone is simple, with a cross and "Asa Gray 1810–1888." The Asa Gray Garden at the cemetery is named in his honor.

Legacy

Life Work

Besides the "Asa Gray disjunction," one of Gray's biggest achievements was creating a huge network of scientists who shared ideas and communicated with each other. He is considered the most important American botanist of the 1800s.

On Gray's 75th birthday, American botanists gave him a silver vase and a silver tray to show their respect. The poet James Russell Lowell also wrote a poem for him.

Namesakes

- The plant toxin Grayanotoxin is named after him.

- William Jackson Hooker named the plant genus Grayia after Gray.

- The Asa Gray Award, given by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists, honors botanists for their career achievements.

- Two buildings at Harvard University are named after him: the Asa Gray House (a National Historic Landmark) and the Gray Herbarium.

- A residential building at Stony Brook University is named after him.

- Two mountains are named after him: Gray Peak in New York and Grays Peak in Colorado. Grays Peak is near Torreys Peak, named after his friend John Torrey.

- In 2011, the US Postal Service released an Asa Gray postage stamp as part of its American Scientists series. The stamp features the Shortia galacifolia flower, which Gray loved.

- A street in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where the University of Michigan is located, is named Asa Gray Drive.

- Asa Gray Park in Lake Helen, Florida is named in his honor.

Images for kids

-

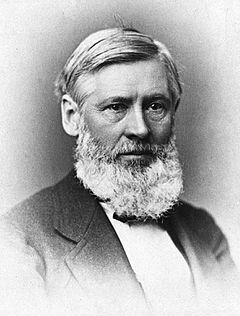

Photograph by John Adams Whipple, 1864

See also

In Spanish: Asa Gray para niños

In Spanish: Asa Gray para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |