Estuary facts for kids

An estuary is a special place where a river meets the sea. Imagine a river flowing along, and then it gets wider and wider as it slowly reaches the ocean. In an estuary, the salty water from the sea mixes with the freshwater from the river. This mix creates a unique type of water called brackish water.

Estuaries can be found in many different places like bays, marshes, swamps, and inlets. If you look at an estuary from above, it often looks like it's curving and bending to find its way to the sea. They come in all shapes and sizes, depending on where they are and the climate of the area. Some estuaries are huge, like large ocean bays where several rivers flow into them. For example, Chesapeake Bay is a very big estuary where many rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean.

Contents

What is an Estuary?

The word "estuary" comes from a Latin word, aestuarium, which means a tidal inlet of the sea. It's also related to aestus, meaning tide. Simply put, an estuary is a coastal area that is partly enclosed. It has a clear connection to the open sea, and the seawater inside it gets mixed with freshwater from rivers and streams.

This special mix of waters makes estuaries very active places. The sea water enters with the rhythm of the tides, and the fresh water flows in from rivers. The way the water mixes can be different in each estuary. It depends on how much freshwater flows in, how strong the tides are, and how much water evaporates.

Home for Plants and Animals

Estuaries usually have shallow waters, which means sunlight can reach all the way to the bottom. This is great for plants like marsh grasses, algae, and other types of plants. These plants then become food for many different animals, including fish, crabs, oysters, and shrimp.

Estuaries are super important because they act like nurseries for many young fish and other sea animals. These young creatures grow up safely in the estuary before they move out to the open ocean. Many sea birds also build their nests in estuaries.

The United States government even has a special program called the National Estuarine Research Reserve System. This program studies and protects the natural environment in many estuaries. Sadly, many estuaries are in danger because they are also popular places for people to live and build cities. A lot of the world's biggest cities are located near or on estuaries.

How Estuaries are Formed

Estuaries can be formed in different ways, often depending on the geology and climate of the area.

Drowned River Valleys

These are also called coastal plain estuaries. Imagine a river valley, and then the sea level rises. The sea water slowly fills up the river valley, creating an estuary that still looks like a river valley. This is the most common type of estuary in places with moderate climates. Good examples are the Severn Estuary in the United Kingdom and the Ems Dollart Region between the Netherlands and Germany.

Lagoon-Type or Bar-Built Estuaries

These estuaries are found where sand and other materials have built up over time. They are shallow and often separated from the sea by sand spits or barrier islands. They are common in warmer, tropical, and subtropical areas. These estuaries are partly cut off from the ocean by these sandy barriers.

These barriers can form in several ways:

- Waves can build up sand from the seafloor into long bars parallel to the coast.

- Rivers can bring sediment, which waves, currents, and wind then shape into beaches and dunes.

- Old beach ridges on the mainland can be flooded by rising sea levels, creating shallow lagoons.

- Long sandy spits can grow from the erosion of headlands due to currents along the shore.

Fjord-Type Estuaries

Fjords are long, narrow inlets of the sea with steep sides. They were formed by huge glaciers during the Pleistocene Ice Age. These glaciers carved out deep, U-shaped valleys. At the mouth of a fjord, there are often rocky bars or underwater sills made of glacial deposits. These sills can change how the water moves in the estuary.

Fjord-type estuaries are found in cold climates, like along the coasts of Alaska, the Puget Sound area in Washington state, British Columbia, eastern Canada, Greenland, Iceland, New Zealand, and Norway.

Tectonically Produced Estuaries

These are rarer estuaries formed by the movement of the Earth's land. This can happen due to faults, volcanoes, or landslides that cut off a piece of land from the ocean.

A famous example is San Francisco Bay. It was formed by the movement of the San Andreas Fault system. This movement caused the lower parts of the Sacramento River and San Joaquin River to be flooded by the sea.

How Water Moves in Estuaries

The way freshwater and saltwater mix and move in an estuary can be classified into different types.

Salt Wedge Estuaries

In this type, a lot of freshwater flows from the river. The lighter freshwater floats on top of the heavier saltwater. The saltwater forms a wedge shape along the bottom, getting thinner as it goes further inland. As the two layers move at different speeds, they create waves that mix some of the saltwater upwards into the freshwater. The Mississippi River estuary is an example of this.

Partially Mixed Estuaries

Here, the tides are stronger, and the river's freshwater flow is less than the saltwater coming in. This causes more mixing between the fresh and salt water. Examples include the Chesapeake Bay and Narragansett Bay.

Well-Mixed Estuaries

When the tidal forces are very strong, they mix the water so much that the freshwater and saltwater layers almost disappear. The water column becomes well-mixed from top to bottom. The lower parts of Delaware Bay and the Raritan River in New Jersey are examples of well-mixed estuaries.

Inverse Estuaries

These estuaries are found in dry climates where a lot of water evaporates. A zone with very high saltiness forms. Both river water and seawater flow towards this salty zone near the surface. This water then sinks and spreads along the bottom, both towards the sea and further inland. Spencer Gulf in South Australia is an example.

Intermittent Estuaries

The type of this estuary changes a lot depending on how much freshwater flows in. It can switch from being almost entirely marine (like the open sea) to any of the other estuary types.

Why Estuaries are Important for Sea Life

Estuaries are very active places where temperature, saltiness, cloudiness of water, depth, and flow change every day with the tides. This constant change makes estuaries very productive habitats. However, it also makes it tough for many species to live there all year round.

Because of this, the types of fish found in estuaries change with the seasons. In winter, you'll mostly find tough marine animals that live there all the time. In summer, many different marine and migratory fish move into and out of estuaries. They come to take advantage of the rich food supply.

Estuaries are vital homes for many species that need them to complete their life cycles. For example, Pacific Herring lay their eggs in estuaries, and young flatfish and rockfish move there to grow. Salmon and lampreys use estuaries as pathways during their migrations. Also, migratory birds, like the black-tailed godwit, depend on estuaries.

Two big challenges for life in an estuary are the changing salinity (saltiness) and sedimentation (stuff settling at the bottom). Many fish and invertebrates have special ways to deal with these changes. Some animals also burrow into the mud to hide from predators and live in a more stable environment. However, the mud often has a lot of bacteria that use up oxygen, which can make the conditions difficult for other animals.

Tiny plants called phytoplankton are very important food producers in estuaries. They float with the water and can be moved in and out by the tides. How much they grow depends a lot on how cloudy the water is.

It's also important to remember that a main food source for many estuary organisms, including bacteria, is detritus. This is made up of dead plants and animals that settle to the bottom.

How Humans Affect Estuaries

Estuaries are beautiful and useful, but they are also in danger from human activities. Many of the world's largest cities are built on or near estuaries.

Human activities like pollution and overfishing threaten these important ecosystems. Estuaries are also affected by sewage, coastal development, and clearing land. Waste from industries, farms, and homes flows into rivers and then into estuaries. Harmful things like plastics, pesticides, and heavy metals can end up in estuaries and don't break down easily.

These harmful substances can build up in the bodies of aquatic animals. This process is called bioaccumulation. They also build up in the mud at the bottom of estuaries. This mud can even show a record of human activities from the last century.

For example, pollution from industries in China and Russia, including harmful chemicals and heavy metals, has badly damaged fish populations in the Amur River and its estuary.

Estuaries naturally receive nutrients from land runoff. But human activities add even more chemicals from farm fertilizers and waste from livestock and people. Too many of these chemicals can use up the oxygen in the water, leading to hypoxia and creating "dead zones" where little can live. This harms water quality and reduces fish and other animal populations.

Overfishing is another big problem. The Chesapeake Bay once had a huge population of oysters. These oysters helped filter pollutants from the water. They would either eat the pollutants or turn them into harmless packets that settled on the bottom. Historically, the oysters could filter all the water in the estuary in just a few days. Today, because of overfishing, it takes almost a year. This allows sediment, nutrients, and algae to cause many problems in the local waters.

Images for kids

-

The New York–New Jersey Harbor Estuary from space.

-

The River Exe estuary seen from a balloon.

-

The mouth of an estuary in Darwin, Australia.

-

The Río de la Plata estuary.

-

The estuary mouth of the Yachats River in Yachats, Oregon.

-

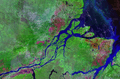

The Amazon estuary.

See also

In Spanish: Estuario para niños

In Spanish: Estuario para niños