Sioux language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sioux |

|

|---|---|

| Dakota, Lakota | |

| Native to | United States, Canada |

| Region | Northern Nebraska, southern Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, northeastern Montana; southern Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan |

| Native speakers | 25,000 (2015)e18 |

| Language family |

Siouan

|

| Official status | |

| Official language in | |

| Linguasphere | 62-AAC-a Dakota |

The Sioux language is a language spoken by the Sioux people. More than 25,000 people in the United States and Canada speak it. This makes it one of the most spoken Native American languages. It is the fifth most spoken indigenous language in the U.S. or Canada. Other popular languages include Navajo, Cree, Inuit languages, and Ojibwe.

Since 2019, the Sioux language has been the official native language of South Dakota. The language of the Great Sioux Nation includes three main ways of speaking, called dialects. These are Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota.

Contents

Different Ways of Speaking Sioux

The Sioux language has three main ways of speaking, or dialects. There are also smaller differences within these main groups.

- Lakota (also called Lakȟóta or Teton Sioux)

- Western Dakota (also called Yankton-Yanktonai or Dakȟóta)

- Yankton (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ)

- Yanktonai (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna)

- Eastern Dakota (also called Santee-Sisseton or Dakhóta)

- Santee (Isáŋyáthi: Bdewákhathuŋwaŋ, Waȟpékhute)

- Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ)

Western Dakota is like a bridge between Eastern Dakota and Lakota. Its sounds are more like Eastern Dakota. But its words and grammar are much closer to Lakota. This means Lakota and Western Dakota speakers can understand each other well. However, they might find it harder to understand Eastern Dakota speakers.

The Assiniboine and Stoney languages are very similar to Sioux. People who speak Assiniboine or Stoney call their own language Nakhóta or Nakhóda.

How Sioux Dialects Compare

The different Sioux dialects have some differences in how they sound and what words they use.

Different Words

Here are some words that are different in the various Sioux dialects:

| English word | Santee-Sisseton | Yankton-Yanktonai | Lakota | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Lakota | Southern Lakota | |||

| child | šičéča | wakȟáŋyeža | wakȟáŋyeža | |

| knee | hupáhu | čhaŋkpé | čhaŋkpé | |

| knife | isáŋ / mína | mína | míla | |

| kidneys | phakšíŋ | ažúŋtka | ažúŋtka | |

| hat | wapháha | wapȟóštaŋ | wapȟóštaŋ | |

| still | hináȟ | naháŋȟčiŋ | naháŋȟčiŋ | |

| man | wičhášta | wičháša | wičháša | |

| hungry | wótehda | dočhíŋ | ločhíŋ | |

| morning | haŋȟ’áŋna | híŋhaŋna | híŋhaŋna | híŋhaŋni |

| to shave | kasáŋ | kasáŋ | kasáŋ | glak’óǧa |

Writing the Sioux Language

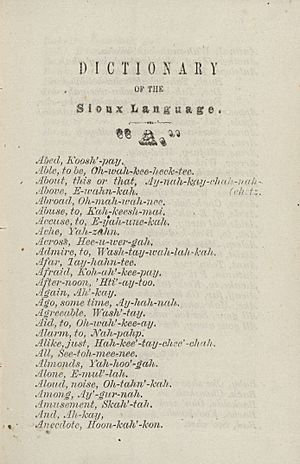

In 1827, John Marsh and his wife, Marguerite, created the first dictionary of the Sioux language. Marguerite was half Sioux. They also wrote a "Grammar of the Sioux Language." A grammar book explains how a language works.

Life for the Dakota people changed a lot in the 1800s. They had more contact with white settlers, especially Christian missionaries. The missionaries wanted to teach the Dakota about Christian beliefs. To do this, they started writing down the Dakota language.

In 1836, brothers Samuel and Gideon Pond, Rev. Stephen Return Riggs, and Dr. Thomas Williamson began translating hymns (church songs) and Bible stories into Dakota. By 1852, Riggs and Williamson had finished a Dakota Grammar and Dictionary. Eventually, the entire Bible was translated into Dakota.

Today, you can find many texts in Dakota. Traditional stories, children's books, and even games like Pictionary and Scrabble have been translated. But writing Dakota still has challenges. Many different missionaries created their own ways of writing the language. Since the 1900s, professional linguists have also made their own writing systems. The Dakota people have also made changes.

Having so many different ways to write the language can cause problems. It can confuse people and lead to disagreements. It also makes it hard to share learning materials for students.

Before the Latin alphabet (the alphabet we use for English) was introduced, the Dakota had their own writing system. It used pictographs. Pictographs are drawings that show exactly what they mean. For example, a drawing of a dog meant "dog."

These pictographs were useful. The Lakota people used them to keep records of years in their "winter counts." These records can still be understood today. In the 1880s, government officials even accepted pictographs. People would use boards or animal hides with drawings of their names for census records.

However, missionaries found it hard to translate the Bible using pictographs. It was not practical for such a long and detailed text.

How the Language is Built

Word Building (Morphology)

Dakota is an agglutinating language. This means it builds words by adding small parts (like prefixes, suffixes, and infixes) to a main word. Each part has a special job.

For example, the ending –pi is added to a verb (an action word). It shows that many living things are doing the action.

- ma-khata means "I am hot."

- khata-pi means "they are hot." (pi shows "they" are many)

Another example is the prefix wicha-. This is added to a verb to show that the action is happening to many living things.

- wa-kte means "I kill him."

- wicha-wa-kte means "I kill them." (wicha- shows "them" are many)

Sometimes, a small part can be added inside a word. This is called an infix. This happens when a sentence talks about two "patients" (people or things affected by the action).

- iye-checa means "to resemble."

- iye-ni-ma-checa means "you resemble me." (ni and ma are added inside)

Sentence Structure (Syntax)

Dakota sentences usually follow a Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) order. This means the person or thing doing the action comes first, then the person or thing receiving the action, and finally the action word itself.

For example:

- wichasta-g wax aksica-g kte means "the man killed the bear." (Man - Bear - Killed)

- wax aksicas-g wichasta-g kte means "the bear killed the man." (Bear - Man - Killed)

The order of words helps show who is doing what in the sentence.

In Dakota, the verb is very important. There are many verb forms. Verbs are sorted into two main types: stative and active. Active verbs are then divided into transitive (acting on something) or intransitive (not acting on something).

Here are some examples of how verbs change:

- Stative (describes a state of being):

- ma-khata – "I am hot"

- khata-pi – "they are hot"

- Active Intransitive (action, no direct object):

- wa-hi – "I arrive"

- hi-pi – "they arrive"

- Active Transitive (action on a direct object):

- wa-kte – "I kill him"

- wicha-wa-kte – "I kill them"

- ma-ya-kte – "you kill me"

The way Dakota sounds, its word building, and its sentence structure are quite detailed. There are many rules that become more specific as you look closer. Sometimes, different experts have slightly different ideas about how the language works. This can make it a bit tricky to study.

See also

In Spanish: Idioma siux para niños

In Spanish: Idioma siux para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |