Squamish people facts for kids

The Squamish people (or Sḵwx̱wú7mesh in their own language, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh snichim) are an Indigenous people from the Pacific Northwest Coast. They have lived in their traditional lands for over a thousand years. In 2012, there were 3,893 registered members of the Squamish Nation.

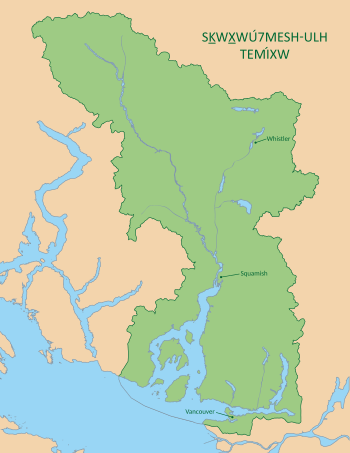

Their language, also called Sḵwx̱wú7mesh snichim, is part of the Coast Salish languages. Sadly, it is nearly extinct, with only about 10 fluent speakers left in 2010. The Squamish people's traditional territory is in what is now southwestern British Columbia, Canada. It stretches from Point Grey in the south, up to Roberts Creek on the Sunshine Coast, and along Howe Sound. It also includes the Squamish, Cheakamus, Elaho, and Mamquam rivers, going past Whistler, British Columbia up the Cheakamus River. The southern and eastern parts include Indian Arm, Burrard Inlet, False Creek, English Bay, and Point Grey.

Today, most Squamish people live in seven communities. These are located in West Vancouver, North Vancouver, and near the District of Squamish.

For a long time, the Squamish people passed down their history, culture, and knowledge through oral tradition (stories and teachings spoken aloud), not through writing. This tradition is still very important today. When Europeans arrived in 1791, they brought diseases that greatly changed the Squamish people and their way of life. In the early 1900s, Charles Hill-Tout was the first European to write down some Squamish oral histories. Later, many experts worked with Squamish elders to record their culture and history.

Even before the first recorded contact with Europeans like George Vancouver in 1791, diseases had already reduced the population in the 1770s. More diseases, like influenza, continued to cause a lot of harm. Newcomers, the loss of their lands, and policies from the Canadian government that tried to make them change their ways, all led to big shifts in their culture and society.

Contents

Squamish History: A Look Back

Stories from the Past: Oral Tradition

Oral tradition is how the Squamish people have shared their history, stories, laws, and knowledge for many generations, without writing things down. This is how most of their history has been kept alive. Passing on this history was seen as the "duty of responsible elders." People who knew a lot were highly respected.

Like other Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, the Squamish have stories about "Transformer" brothers. These brothers traveled the world, changing things and people. Other stories tell about ancestors and the important events they were part of. Even today, new events and history continue to be shared through oral tradition.

Squamish oral history tells about the "founding fathers" of their people. An elder named Mel̓ḵw’s, who was over 100 years old, shared a story in 1886. He said that at first, "water was everywhere." Then, mountain tops appeared from the sea, and land was formed. The first man was named "X̱i7lánexw." He was given a wife, a tool, and a salmon trap. X̱i7lánexw and his wife had many children, and the Squamish people are their descendants. Dominic Charlie told a similar story in 1965.

Their oral history also includes a story about the Great Flood. In a story from Chʼiyáḵmesh (Cheakamus) in the Squamish Valley, a man survived the flood. He was walking down the river, sad about losing his people. The Thunderbird helped him and gave him food. The Thunderbird then told him where to stay and promised him a wife. This is how the people of Chʼiyáḵmesh came to be. Another story tells of two first men, Tseḵanchtn and Sx̱eláltn, who appeared at Chekw’élhp and Sch’enḵ, now known as Gibsons, British Columbia. They had large families, and many Squamish people today are related to them.

Tough Times: Disease Epidemics

In the 1770s, smallpox was a terrible disease that killed at least 30 percent of Indigenous people on the Northwest Coast, including many Squamish. This was one of the deadliest diseases to hit the region over the next 80 to 100 years. Between 1770 and 1850, smallpox, measles, influenza, and other illnesses wiped out many villages.

Squamish oral histories describe the 1770s epidemic. An elder told a story in the 1890s about a terrible sickness. He said that one salmon season, the fish were covered in sores, making them unsafe to eat. Because people relied on salmon for winter food, they had to eat them anyway. This led to a "dreadful skin disease" that affected everyone. Hundreds of people died, leaving many villages empty. The elder said that the remains of these old villages can still be found today. Slowly, the few survivors grew into a strong nation again.

The 1770s epidemic was the first and most damaging. More outbreaks followed, including smallpox in 1800–01, influenza in 1836–37, measles in 1847–48, and another smallpox epidemic in 1862.

New Ways: European Colonization and Reserves

In 1792, the Squamish people first met Europeans when British Captain George Vancouver and Spanish Captain José María Narváez sailed into Burrard Inlet. The arrival of Europeans, the fur trade boom, the gold rush, and later colonization policies by the Canadian government brought big changes to the Squamish way of life. Within a few years, the Squamish became a small minority in their own lands. This was due to more diseases, losing their land, and the growing number of European and Asian settlers.

In the early 1800s, Fort Langley became an important trading post for the Hudson's Bay Company. The Squamish traded with Fort Langley. In 1858–59, the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush brought even more settlers to the territory. However, major settlement didn't really begin until the Canadian Pacific Railway was finished, bringing more people from eastern Canada.

In 1876, the Indian Act was passed. The Joint Indian Reserve Commission then set aside specific areas of land called Indian reserves for Indigenous people. These reserves were managed by "Indian agents" from the government. Many reserves were created on existing village sites. Chiefs were then chosen to lead each reserve.

Around this time, some reserve lands were sold, sometimes illegally. For example, parts of the Kitsilano Indian Reserve, where the village of Sen̓áḵw was located, were taken in 1886 and 1902. Families living there were forced to leave and were promised payment. They were put on a barge and sent up the Squamish River area. It wasn't until 1923 that the different reserve chiefs joined together to form the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw to manage all their reserves as one group.

In 1906, a group of chiefs from British Columbia, including Joe Capilano, traveled to London. They wanted to speak with King Edward VII about the land taken by the Canadian government. But their requests to see the King were denied.

Squamish Lands and Homes

The Squamish homeland is a thick temperate rainforest. It has many conifer trees like Douglas-fir, Western red cedar, and Western Hemlock, along with maple and alder trees. There are also large areas of swampland. The biggest old-growth trees were found around Burrard Inlet, the slopes of Sen̓áḵw, and the area now called False Creek. All these natural resources helped the Squamish people have a rich culture.

The traditional Squamish territory covers a huge area of about 673,540 hectares. In the mid-1800s, Squamish people started living more permanently in Burrard Inlet to work in mills and trade with settlers. The southern parts of their territory, including Indian Arm, Burrard Inlet, False Creek, English Bay, and Point Grey, are now considered the southern border. Traditionally, Squamish lands went past Point Atkinson and Howe Sound as far as Point Grey. From there, it went north to Roberts Creek on the Sunshine Coast and up Howe Sound. The northern part included the Squamish, Cheakamus, Bowen Island, Elaho River, and Mamquam River. Up the Cheakamus River, Squamish territory included land past Whistler, British Columbia.

Squamish territory also shared borders with other Indigenous peoples. Their land overlaps with the Musqueam, Tseil-waututh to the south, and the Lil'wat to the north. These neighbors also have Squamish names: the Tseil-waututh are Sel̓íl̓witulh, the Shishalh are Shishá7lh, the Musqueam are Xwmétskwiyam, and the Lil'wat are Lúx̱wels. Roberts Creek is the border between Squamish and Shishalh territory. The Squamish are culturally and historically similar to the Tseil-waututh, but they are politically separate. Through marriages between families, they often shared rights to places for gathering resources.

Vancouver and nearby cities are located within traditional Squamish territory. This makes the Squamish one of the few Indigenous peoples in Canada with communities in or near big cities. Out of their vast traditional territory, less than 0.5% is currently reserve land given to the Squamish Nation. Most Squamish communities today are on these reserves.

Villages and Communities

The Squamish people live both within and outside their traditional territory. Most live on Indian reserves (about 2,252 people) within the Squamish territory. There are communities on 9 of the 26 Squamish reserves. These communities are in North Vancouver, West Vancouver, and along the Squamish River. The reserves are located on sites that have been villages, camps, or important historical places for a long time.

In the past, large extended families lived in big longhouses in the old villages. One such house was recorded in what is now Stanley Park at the old village of X̱wáy̓x̱way in the late 1880s. It was about 60 meters long and 20 meters wide, and 11 families were said to live there.

Here is a list of Squamish villages, both old and new, with their reserve names and other details.

| Squamish Name | IPA | Meaning | Location | Other names used in English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sen̓áḵw | IPA: [sənakʷ] | Inside Head | Kitsilano Indian Reserve No. 6; Vanier Park; Vancouver, British Columbia | Snauq, Snawk |

| X̱wáy̓x̱way | IPA: [xʷajxʷaj] | Place of Masks | Lumberman’s Arch; Stanley Park | Whoi Whoi |

| Xwmélch’tstn or Xwmélts’stn | IPA: [xʷəməltʃʼstn] | Fast Rolling Waters | Capilano Indian Reserve No.5; West Vancouver, British Columbia | Capilano, Humulchstn |

| Eslhá7an | IPA: [əsɬaʔan] | Up against it. | Mission Indian Reserve No.1; North Vancouver | Ustlawn, Eslahan, Uslawn |

| Ch’ích’elxwi7ḵw | IPA: [tʃiʔtʃʼəlxʷikʷʼ] | Fishing weir village | Seymour Creek Indian Reserve No. 2; Seymour River, North Vancouver | None. |

| Átsnach | IPA: [Unknown] | Bay | Burrard Inlet Reserve No.3; North Vancouver | None. |

| Ch’ḵw’elhp or Schen̓ḵ | IPA: [tʃəkʷəɬp] or IPA: [stʃənk] | No translation available. | Chekwelp Indian Reserve No. 26, Gibsons, British Columbia | Chekwelp; Schenk |

| Ḵ’íḵ’elx̱en | IPA: [kʼikʼəlxn] | Little Fence | Kaikalahun Indian Reserve No. 25, Port Mellon, British Columbia | Kaikalahun |

| Tsítsusem | IPA: [tsitsusəm] | No translation available. | Potlatch Creek, Howe Sound, British Columbia | None |

| St’á7mes | IPA: [staʔməs] | No translation available. | Stawamus Indian Reserve No. 24, below Stawamus Chief Mountain | Stawamus |

| Yékw’apsem | IPA: [jəkʷʼapsəm] | Upper part of the neck. | Yekwaupsum Indian Reserve No. 18; Squamish, British Columbia. | Yekwaupsum |

| Ḵw’éla7en | IPA: [Unknown] | Ear | Yekwaupsum Indian Reserve No. 18; Squamish, British Columbia, The Shops. | None |

| Kaw̓tín | IPA: [kawtin] | No translation available. | Kowtain Indian Reserve No. 17; Squamish, British Columbia | Kowtain |

| Siy̓ích’em | IPA: [Unknown] | Already full | Seaichem Indian Reserve No. 16; Squamish, British Columbia | Seaichem |

| Wíwḵ’em | IPA: [wiwkəm] | Open mouth | Waiwaikum Indian Reserve No. 14; Squamish, British Columbia | Waiwaikum |

| Puḵway̓úsem | IPA: [Unknown] | Have a mouldy face | Poquiosin Indian Reserve No. 13; Squamish, British Columbia | Poquiosin |

| Ch’iyáḵmesh | IPA: [tʃijakməʃ] | Fish Weir People; People of the Fish Weir | Cheakamus Indian Reserve No. 11; Squamish, British Columbia | Cheakamus |

| Skáwshn | IPA: [Unknown] | Foot descending | Skowishin Indian Reserve No. 7; Squamish, British Columbia | Skowishin |

| P’uy̓ám̓ | IPA: [pujam] | Blackened from smoke | Poyam Indian Reserve No. 9; Squamish, British Columbia | Poyam |

Squamish Society and Culture

Leaders and Decisions: Family Governance

In traditional Squamish society, each family had a siy̓ám̓. This word roughly means "highly respected person." The siy̓ám̓ would act in the best interest of their family. They made decisions based on what the whole family agreed upon. A siy̓ám̓ was often described as "the best talker" who said "the most wise things."

A siy̓ám̓ was usually chosen based on their respect in the community and with other Indigenous nations. They also had to show qualities like humility, respect, generosity, and wisdom.

How Society Was Organized

The Squamish class system was similar to other Coast Salish peoples. Unlike a European pyramid structure, Squamish society was more like an upside-down pear. The largest group was the nobility and aristocrats. Commoners made up a smaller but still significant part of society. The smallest group was slaves, who were only owned by high-ranking nobles.

Nobility was recognized by three main things:

- Wealth: Especially how much wealth they shared with others.

- Values: How well they and their family lived by the community's values.

- Knowledge: Knowing and sharing history, traditions, culture, and practical skills.

Sharing wealth was highly valued. This was a key part of the potlatch gift-giving festival. It showed important values like generosity, humility, and respect. Some families were noble because of their connection to spiritual powers or ceremonies. Shamans, prophets, and medicine doctors were considered noble because of their special training and skills. Certain jobs, like hunting mountain goats or weaving blankets from goat wool, also showed a person was part of this class. A person's class was not always set for life. Before Europeans arrived, commoners or even slaves could sometimes rise to a higher class.

In Squamish culture, respect for others and generosity (both of wisdom and material things) were very important. Wisdom and knowledge were passed down through spoken and visual teachings. Unlike some Western ideas, the Squamish valued everyone's contributions, even those who were not rich or formally educated. As Andy Paull said, "It was the duty of the more responsible Indians to see that the history and traditions of our race were properly handed down to posterity." Knowing their history and legends was like getting an education. Those who knew a lot were seen as aristocrats.

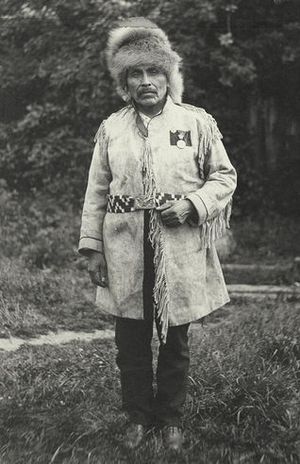

One historical custom was called flat-foreheading. An infant's head would be gently shaped using a wooden model. This shape was considered beautiful and a sign of nobility. Tim Moody was the last known Squamish person to practice this custom.

What Was Considered Property?

In Squamish society, many things were considered property that might not be in European cultures. This included names, stories, ceremonies, and songs. This idea of property is a bit like modern intellectual property laws. Other property included fishing spots, hunting trap lines, berry patches, canoes, and art. Rights to places for hunting, fishing, or gathering food could also be gained by marrying people from other villages or nations.

Names were a special type of property passed down through generations. A young person would often receive a name from a deceased ancestor after a special ceremony. Before getting this "ancestral name," children were called by "nicknames." These ancestral names are very important because they connect people to their family history. Names were only passed down through a blood connection to the ancestor.

Places and resources were not always defined with clear boundary lines like in European law. Sometimes landmarks served as markers. The value and ownership of a place usually came from a valuable resource there, like salmon streams, herring spawning grounds, berry patches, or fishing holes.

Family and Relatives

Squamish family structure was based on a loose patrilineal system, meaning family lines were often traced through the father's side. They lived in large extended families in communal villages. Each village had many longhouses, and each longhouse was like its own community with several related families living together. The number of families depended on the size of the house. In warmer seasons, each family might have its own fire. In winter, one fire was used for ceremonies and spiritual work.

Historically, marriages were either arranged, or the groom would ask the prospective wife's father for permission. If the father agreed, he would invite the groom into his house after testing the young man. Only the wealthiest individuals sometimes had more than one spouse.

Squamish Culture and Daily Life

Changes Over Time

Over the past few hundred years, Squamish culture has changed a lot since contact and colonization began. The history of Residential Schools and the potlatch ban were times when the Canadian government tried to stop their cultural practices. This led to many problems for decades, including their language almost disappearing, people being forced to adopt Western ways, and lasting harm passed down through generations.

Despite these challenges, much of their culture is still strong. Some parts of their culture are now only historical, some have changed for the modern world, and some new cultural practices have developed.

Customs and How They Lived

Squamish daily life centered around the village community. Before European contact, a village had many Longhouses, where large extended families lived. Inside a longhouse, different parts of the family would live in different areas. A typical house was about 30 feet wide, 40 feet long, and 19-13 feet high, but sizes varied. Many villages were located near important resources or cultural sites. Families in different villages were connected through kinship ties.

Salmon was the most important food, and it was once very plentiful. Other seafood like herring, shellfish, and seal were also eaten. Berries and plant roots were also part of their diet. This formed the basis of their daily life.

Big longhouses were also used for celebrations and ceremonies. These included naming ceremonies, funerals, memorials, weddings, and spiritual events. Elaborate events called a "potlatch" (a word meaning to give from the Chinook Jargon) were hosted by a family. A person's standing in the community was based on how much they gave to their people. So, at potlatches, gifts and wealth were shared with the community. Food was prepared, and a large feast was given. All the foods eaten by their ancestors are considered "traditional foods" and are often part of these feasts. The Canadian government banned the potlatch from 1884 to 1951. During that time, ceremonies went underground, but they were later brought back.

Before European contact, people traveled mainly by canoe. Large cedar trees were cut down and carved into single dug-out canoes. Families would travel to different villages or nations to visit relatives. In summer, they would journey to rich camping sites to gather food and materials for the colder winter months. In 1992, the Squamish people began building canoes again, bringing back this important part of their culture. They built a 52-foot ocean-travel canoe from a single cedar tree. Since then, many more canoes have been carved for families and the community.

Language: Keeping It Alive

The Squamish language, or Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim, is the traditional language of the Squamish people. It is seen as a very important part of bringing their culture back to life. Even though it is nearly extinct, it is still used in ceremonies, events, and some basic conversations. Since no children are learning it as a first language and all fluent speakers are over 65, a lot of effort is being made to save and revive it.

The language is part of the Coast Salish language family. It is most closely related to Sháshíshálh (Sechelt), Halkomelem, and Lhéchalosem. Many experts have worked with Squamish people and their language, including Franz Boas and Charles Hill-Tout.

Before European contact, Squamish was the main language in all villages, along with the Chinook Jargon. Most children would learn Chinook first because it was simpler, then Squamish as they grew older. After diseases caused huge population drops and colonization began, Squamish became a minority language in its own lands. When the Canadian government forced policies to make Indigenous people change their culture and language, a residential school was set up in the village of Eslha7an. Children from many Squamish villages were sent there. At the school, children were forbidden to speak their Squamish language. This made people afraid to speak the language, and so the next generation grew up without knowing their native tongue.

Over the years, English became the main language. Then, in the 1960s, a lot of work began to help bring the Squamish language back. Randy Bouchard and Dorothy Kennedy led the BC Language Project, which documented the language and created the writing system used today. Eventually, a local elementary school and a high school started offering Squamish language classes instead of French. A children's school called Xwemelch'stn Estimxwataxw School, meaning Xwmelch'stn Littleones School, was built for kindergarten to grade 3. It aims to teach children through language immersion, with plans to expand into a full immersion program.

Squamish Food and Diet

What They Ate: Nutrition

The Squamish people had smart ways of managing their land. This helped keep the environment healthy and full of resources. Their "forest gardens" on the Northwest Coast included plants like crabapple, hazelnut, cranberry, wild plum, and wild cherry. Squamish territory had many rich food sources from land animals, sea life, and plants.

For meat, they ate deer, bear, elk, duck, swan, and small animals like squirrels. From the ocean, they gathered mussels, sea eggs, cockles, clams, seaweed, herring, trout, crab, urchin, sea lion, and seal. They also ate all kinds of salmon. For berries and plants, they had different kinds of wild blueberry, blackberry, salmon berry, salal berry, five different kinds of grass, and the roots of various plants. Ooligan fish were once in their rivers, and Ooligan grease was made from them.

Seafood, especially salmon, was their main staple food. Their diet was rich in natural fats and oils from these foods, with fewer carbohydrates. To get all the important vitamins, they ate almost all parts of the animals they harvested. Ground shells, algae, and seaweeds provided calcium. Vitamin A came from liver. Vitamin C was found in berries and some other plants. Intestines and stomachs could be eaten for vitamin E and B vitamins. Within ten years of Fort Langley being built in 1827, the Squamish also started growing a lot of potatoes.

The Importance of Salmon

As the most important food, salmon was highly respected in Squamish culture. Every spring, they held a Thanksgiving Ceremony or First Salmon Ceremony. Special fish were prepared for community gatherings. After the feast, they followed an old ritual: they returned the salmon bones to the water. This was done so the salmon could come back again.

A story tells how salmon came to the Squamish people. The salmon have their own world, an island far out in the ocean. Every year, they come to sacrifice themselves to feed the people. In return, the people were asked to return the salmon bones to the ocean so the salmon could return.

Salmon were caught in many ways. The most common was the fishing weir. These traps allowed skilled hunters to easily catch many fish. Fishing weirs were regularly used on the Cheakamus River, which gets its name from the village of Chiyakmesh. This name means People of the Fish Weir, showing how important this method was there. This way of fishing needed a lot of teamwork between the men fishing and the women on the shore who cleaned the fish.

In the past, salmon would be roasted over fires and eaten fresh, or dried to preserve them. Using smoke from alder or hemlock fires preserved salmon for up to two years. Later, this evolved into canning salmon. Canned salmon was jarred or pickled and stored for the winter months.

Notable Squamish People

|

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |