Stawamus Chief facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Stawamus Chief |

|

|---|---|

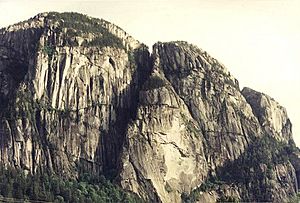

Stawamus Chief, second peak seen from the first

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 702 m (2,303 ft) |

| Prominence | 417 m (1,368 ft) |

| Geography | |

| Location | British Columbia, Canada |

| Parent range | Pacific Ranges |

| Topo map | NTS 92G/11 |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Formed Late Cretaceous Exposed Holocene |

| Mountain type | Granite dome |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | Prehistoric |

| Easiest route | Hike |

The Stawamus Chief, often called The Chief, is a huge granite rock mountain in Squamish, British Columbia, Canada. It stands over 700 meters (about 2,300 feet) tall, looking down on the waters of Howe Sound. It's one of the biggest granite rocks in the world!

The Squamish people, who are the original inhabitants of this area, see The Chief as a very special and spiritual place. In their language, it's called Siám' Smánit. Their stories say that the mountain was once a longhouse that was turned into stone by Xáays, who are powerful spirit brothers. The big crack you see in the mountain's side is said to be a mark left by the skin of Sínulhka, a giant two-headed sea serpent from their legends.

The mountain got its English name from the nearby village of Stawamus. The Stawamus River and Stawamus Lake are also named after this village.

Contents

Explore Stawamus Chief Provincial Park

In 1997, the Stawamus Chief Provincial Park was created by the government of British Columbia. This park is huge, covering more than 5 square kilometers. It includes not only The Chief but also a slightly smaller granite dome called Slhanay.

The park has a campground where you can stay. It also has many well-kept hiking trails. These trails go through the forest on the "backside" of The Chief and lead to its different top areas.

In 2009, a new bridge was built over the highway. This bridge makes it easier to get to the park from a new parking lot. It also connects the climbing areas on The Chief to other granite cliffs nearby. This bridge was built as part of the upgrades for the Sea to Sky Highway before the Winter Olympics.

How the Chief Was Formed

The Chief is made of a type of rock called granodiorite. This rock formed deep inside the Earth about 100 million years ago. It happened when hot, melted rock called magma slowly cooled down and became solid.

Over millions of years, the rocks on top of the granodiorite wore away. This process, called erosion, slowly brought The Chief to the surface. During the Ice Ages, huge glaciers helped shape the mountain. They carved out the tall, steep walls you see today and also dug out Howe Sound, which is a type of valley called a fjord.

You can still see signs of the glaciers, like smooth, polished rock surfaces with scratches on them. These scratches are even at the very top of The Chief. This tells us that the entire mountain was once covered by a thick layer of ice during the peak of the Ice Age.

The deep cuts or "gullies" that separate the three peaks of The Chief were formed by large blocks of rock breaking off. This happened along natural cracks in the rock.

The Chief might be what's left of an old volcano. This is because there hasn't been any volcanic activity in the Squamish area for a very long time, until about 2-3 million years ago when the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt started forming volcanoes.

What Does the Chief Look Like?

The Chief covers about three square kilometers. It has several peaks separated by deep cuts called gullies. In many places, especially on the western side, steep cliffs drop straight down from the peaks to the forest floor.

The Peaks of The Chief

There are three main peaks on The Chief:

- First Peak or the South Summit (610 meters or 2,000 feet tall)

- Second Peak or the Centre Summit (655 meters or 2,149 feet tall)

- Third Peak or the North Summit (702 meters or 2,303 feet tall)

Each peak has large areas of smooth, glacier-polished rock. From these spots, you can see amazing views in every direction. Third Peak is a bit harder to reach and not as many tourists go there.

There's also another peak area to the north called the Zodiac Summit. It's very isolated, and there isn't a clear trail to get there, just faint paths through the trees.

Hiking the Trails

You can reach all three main peaks using the hiking trails on the backside of The Chief. These trails are steep and rugged. In some very steep or slippery spots, there are chains and ladders bolted to the rock to help you climb. The main reason people visit The Chief is for its huge granite face, which you can reach by hiking or by rock climbing. From the peaks, you get great views of the Sea to Sky highway 99 and the river below. Be careful, though, as there are no railings or safety fences on the summits, so it's important to watch your step.

Deep Cuts: The Gullies

The three main peaks of The Chief are separated by several deep cuts called gullies. These are steep, narrow valleys partly filled with loose rocks. Glaciers likely carved them out.

- South Gully: This is the biggest and most noticeable gully. It separates First Peak from Second Peak.

- North Gully: This gully is dark and narrow. It's near the north end of The Chief and separates Second Peak from the "Zodiac Summit."

- North-North Gully: Even darker and narrower, this gully separates the "Zodiac Summit" from Third Peak.

There's also a smaller gully near the south end called Bullethead Gully. It's very bushy and not as dramatic as the main gullies.

The Apron

The Apron is a huge, gently sloping rock area. It rises from the highway partway up the Grand Wall, which is near the center of The Chief. It then meets a rock ridge called the Squamish Buttress and ends at the South Gully.

Rock Faces

The peaks of The Chief are surrounded by sheer rock cliffs. These walls are tall, open, and have many different features. Some of the most famous rock faces are:

- Grand Wall: This is the most famous part of The Chief. It's a steep, light-colored wall that rises above highway 99.

- Bulletheads: This area has strangely rounded rock bulges near the southern end of The Chief.

- Dihedral Wall: This rock face is between the Grand Wall and Tantalus Wall. In spring and early summer, peregrine falcons build their nests here.

- Tantalus Wall: This is a sheer cliff face. It's also a nesting area for peregrine falcons.

- Sheriff's Badge: This is a white, star-shaped mark on the rock, northeast of the Apron. Locals sometimes call it "the Witch" or "the Bird."

- Zodiac Wall: Located at the very northern end of The Chief, this rock face is dark, isolated, and not often visited.

The rock faces of The Chief, especially the Grand Wall, show unique patterns. These patterns are from a natural process called granite exfoliation. This is how large granite formations weather and age. Instead of slowly crumbling, large pieces of granite tend to break off in layers and fall from the cliff. When they hit the ground, these broken pieces become boulders and loose rock.

Sometimes, a piece of rock will partly break away but stay attached to the cliff. A great example of this is the famous Split Pillar on the Grand Wall. The Chief's rock faces have many different features, like overhangs, cracks, chimneys, ledges, and flatter slabs.

The Black Dyke

This feature separates the Grand Wall from the Dihedral Wall. It's much younger than the pale granite rock around it. It formed when a crack opened in the solid granite. This crack allowed melted rock (magma) to flow up from deep below. This magma cooled quickly, forming a very fine-grained, dark rock. This dark rock feature, called a dyke, can be clearly seen from the main parking area of The Chief.

The Forest

At the bottom and around the edges of The Chief are thick forests. These forests are typical of the coastal temperate rainforests found in this area. You'll find trees like Douglas fir, western red cedar, Sitka spruce, and alder.

Giant Boulders

At the base of The Chief's walls, you'll also find many different sizes of granite boulders. These boulders were once part of The Chief itself. They have been explored by people who enjoy bouldering, which is a type of rock climbing on large rocks. Some of these boulders are so big they look like small cliffs. The largest one is the Cacodemon Boulder at the base of the Grand Wall. It's as big as a small apartment building!

Rock Climbing Adventures

Because of The Chief and other great climbing spots nearby, Squamish has become a world-famous place for rock climbing. Some people even call Squamish "Yosemite North." The Chief's granite rock is very similar in quality and structure to Half Dome in Yosemite Valley.

Kevin McLane, a well-known rock climber and guidebook writer, says that climbing at The Chief offers "immense vertical walls, long cool slabs, winding dykes, and beautiful cracks." You can try almost every style of rock climbing here, no matter your skill level. This includes traditional climbing, sport climbing, and bouldering. Since The Chief is almost at sea level, you won't find alpine climbing or ice climbing here, but there are plenty of places for those in the nearby Coast Mountains.

The first major climb of The Grand Wall happened in 1961, done by Ed Cooper and Jim Baldwin. Their amazing effort was featured in a 2003 movie called In the Shadow of the Chief.

Famous rock climber Peter Croft started his climbing career in Squamish in the late 1970s. He amazed the climbing world by creating many challenging new routes on The Chief. More recently, Brad Zdanivsky became the first quadriplegic person to reach the summit on July 31, 2005. In 2006, Sonnie Trotter created what was then considered the hardest traditionally protected rock climb in North America, called Cobra Crack.

Slacklining Fun

Slacklining is a newer activity on The Chief compared to rock climbing. Slackliners set up their lines across the deep gullies of The Chief. On August 2, 2015, Spencer Seabrooke broke a world record for walking across a 64-meter gap without being tied in. There are more than seven different lines that slackliners use in various spots on The Chief.

Gallery

-

Atwell Peak as viewed from the height of the North Gully.

-

The Chief's Grand Wall area, a vertical sea of some of the world's finest granite. To the right the Black Dyke can be seen bisecting the rock face.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |