Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami facts for kids

|

|

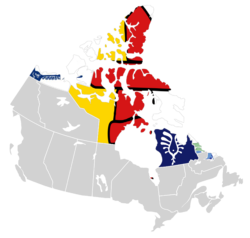

Map of ITK showing the four constituent regions of Inuit Nunangat: Inuvialuit Nunangat, Nunavut, Nunavik, and Nunatsiavut

|

|

| Abbreviation | ITK |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1971 |

| Type | Inuit organization |

| Legal status | active |

| Purpose | advocate and public voice, educator and network |

| Headquarters | Ottawa, Ontario, Canada |

|

Region served

|

Canada |

|

Membership

|

|

|

Official language

|

English, Inuktitut |

|

President

|

Natan Obed |

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (which means "Inuit are united in Canada") is a special group in Canada. It used to be called the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada. This group speaks for over 65,000 Inuit people. These Inuit live across Inuit Nunangat and other parts of Canada.

Their main goal is to protect and help the rights and interests of Inuit in Canada. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) was started in 1971 by Inuit leaders. Since then, it has helped with many important things for Inuit. This includes helping to get land claims agreements. They also share the voice of Inuit and their culture through television. ITK has also taken legal action to protect Inuit rights. They even created a program to make education better for Inuit children. ITK works with the government or sometimes against it to reach its goals. The work of ITK even led to the creation of Nunavut.

History of ITK

How ITK Started

Long ago, before Europeans came, Inuit chose leaders based on their survival skills. Often, the oldest male took this role. But important decisions were usually made by everyone in the group. As more people became interested in Canada's north, more development happened. This meant more non-Inuit people moved to northern Canada.

These new people from the south often worked in government jobs. They also worked in the main industries in the north. These jobs needed a Western education. This gave people from the south an advantage over the Inuit. As more southern Canadians arrived, they wanted goods from the south. This made the Inuit's traditional knowledge less needed by the newcomers. This led to unfairness between Inuit and non-Inuit people in the north. This unfairness was both social and economic.

By the 1960s, there was a push to include Inuit in politics. They started to join government groups. Examples include the Government of the Northwest Territories. They also joined regional and town councils. The Baffin Regional Council was a strong example. It was mostly run by Inuit. But Inuit still worried about not having enough control. They also worried about policies that tried to make them change their ways. They were also concerned about limits on their traditional lands. In 1969, a plan called the White Paper was introduced. This plan wanted to end the special status of Indigenous peoples. It also wanted to make them fit into Canadian society. Because of these worries, Inuit wanted their own political group.

Other groups also shared these concerns. One was the Indian-Eskimo Association (IEA). This group was made of southern Canadian educators and church leaders. They supported First Nations and Inuit. The IEA helped Indigenous peoples speak up for themselves. With the IEA's help and money, the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (ITC) was founded. In 1970, the IEA held a meeting in Coppermine (now Kugluktuk). Inuit from across Canada's Arctic came to talk about their shared concerns. From this meeting, a message was sent to Prime Minister Trudeau. It asked for recognition of indigenous land rights in the north. This was the first time Inuit had sent such a group message to the Canadian government.

Founding of the Organization

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, first known as the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (ITC), was founded in 1971. Seven Inuit community leaders started it. They were at an IEA meeting in Toronto. These leaders were Noah Qumak, Jacob Oweetaluktuk, Celestino Makpah, Josiah Kadlusiak, Ipeele KìLabuk, Tagak Curley, and Mary Cousins. They decided to form a national Inuit organization. Their goal was to speak to the Government of Canada with one voice. They wanted to talk about land and resource ownership in Inuit Nunangat. They also wanted more control over their own lives.

Big projects like the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline started to threaten Inuit Nunangat. So, leaders decided to act. Inuit Nunangat has four regions today. These are the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (northern Northwest Territories and Yukon), Nunavut, Nunavik (northern Quebec), and Nunatsiavut (northern Labrador). Inuit culture is still strong across Inuit Nunangat. About 60% of the people still speak Inuktut. This is the name for several Inuit languages and dialects. They also get traditional foods by hunting marine mammals and caribou. ITK represents 51 communities and 65,000 Inuit in Inuit Nunangat.

After ITK was created, five more Inuit organizations were formed. These include the Northern Quebec Inuit Association (NQIA) in 1971. The Labrador Inuit Association (LIA) was founded in 1973. Other groups like the Kitikmeot Inuit Association were also formed.

Later in 1971, the first conference was held in Ottawa, Ontario. ITK has had its main office in Ottawa since 1972. In 2001, the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada changed its name. It became Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. This new name means "Inuit are united in Canada." The name changed after a land claims agreement was signed for Labrador Inuit. This agreement confirmed Inuit rights to their land. It also helped them become more self-sufficient.

Tagak Curley's Leadership

Tagak Curley was born in 1944 on Southampton Island, Nunavut. He is an Inuk politician and a strong supporter of Inuit rights. Curley was one of the people who started ITK. He was also its first president. He grew up living a traditional Inuit lifestyle. He had strong ties to the land and culture. Before becoming ITK president, he worked on issues like housing in Inuit communities. He worked for the government from 1966 to 1970. After that, he managed a settlement in Naujaat for a year.

Curley was a successful president for four years. He achieved many things. Most notably, he led the effort to change the word Eskimo to Inuit. This change happened in all official Canadian documents. He later worked in politics. In 1979, Curley ran in a federal election.

Protecting Inuit Rights in the Constitution

In 1979, ITK created the Inuit Committee on National Issues (ICNI). This group shared Inuit views on the Canadian constitution. The ICNI was part of a larger group called the Aboriginal Rights Coalition. In 1981, this group successfully worked to put Section 35 back into the Constitution. This section protects Indigenous and treaty rights. The ICNI was present at important meetings about these rights. The ICNI stopped working after its funding ended.

As early as 1976, ITK suggested its first Inuit land claims plan. This plan was not just about land. It also asked for a new territory to be created. This meant settling land claims and developing politically at the same time. This first plan was too complex and was not accepted. A new plan was made in 1977. But it stopped due to political disagreements.

In 1979, the Nunavut Land Claims Project (NLCP) continued the land claims process. That same year, ITK members agreed to a plan for political development in Nunavut. This plan combined ideas from earlier claims. In 1982, the Tunngavik Federation of Nunavut (TFN) was formed. It took over land claims talks from the NLCP. In 1990, a basic agreement was reached. This led to the 1993 approval of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. It also led to the Nunavut Act, which created the territory of Nunavut.

The TFN was replaced by the Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI). The NTI worked to put this new land claim into action. Nunavut was officially created in 1999. The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement is the largest and most complete land claims agreement in Canadian history. It also gives Inuit more self-determination.

ITK's Goals and Focus

ITK's goals have changed as they have made progress. At first, their main focus was protecting Inuit land. In the 1970s and 1980s, Inuit negotiated four land claim agreements. These were with the federal government. The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement was reached in 1975. The Inuvialuit Final Agreement was reached in 1984. The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement was settled in 1993. Finally, the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement was settled in 2003.

Land claims are still important to ITK. But they also focus on social issues for Inuit. These include keeping their culture and Inuit languages alive. They also raise awareness about education, healthcare, and the environment. Climate change and economic development are also important. ITK and other Inuit groups have helped form a partnership with the Government of Canada. This partnership discusses issues in Canada and around the world.

Important Activities

Protecting Hunting Rights

In 1979, ITK tried to stop mining in Baker Lake. The Baker Lake Hunters and Trappers Association, ITK, and 112 Inuit took the Canadian federal government to court. This case was called Hamlet of Baker Lake v. Minister of Indian Affairs. The case was about Aboriginal rights. Specifically, it was about the right to hunt caribou. The Inuit wanted to stop mining. They also wanted it to be declared that Inuit had the right to hunt and fish in Baker Lake. The judge recognized that Aboriginal Title existed in Nunavut.

Inuit Television Project

In the late 1970s, ITK started the Inukshuk Project. It was named after the Inuksuk. This project was the first time Inuit were involved in broadcast television. In 1974, the government decided that all Canadian communities with at least 500 people would get TV in English or French. James Arvaluk, who was ITK president then, disagreed. He felt there was not enough local Inuit representation.

So, they started the Inukshuk Project. It was for the Inuit population. It let them talk about important issues and share information in their own language. From the Inukshuk Project, the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation (IBC) was created in 1980. This TV company is based in Nunavut. Most of its programs are in Inuktitut. The IBC has hired many talented Inuit media people and leaders.

High Arctic Relocation Report

In 1990, ITK complained to the government about Inuit families being moved. In 1953 and 1955, the Canadian Government moved families from Inukjuak in Northern Quebec to the far north. This was part of the High Arctic relocation. The government first said they acted correctly. They would not apologize for moving the Inuit.

ITK then asked the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) to investigate. ITK asked for three things. First, they wanted recognition for Inuit helping Canada claim the High Arctic. Second, they wanted an apology for the hardships Inuit faced in Grise Fiord and Resolute. Third, they wanted payment for the wrongs done to them. The CHRC report suggested the government should thank the Inuit. It also said they should apologize for poor planning. And they should admit they promised Inuit they could return to Northern Quebec within three years.

Improving Inuit Education

In 1976, ITK's first land claims proposal included education reform. The National Strategy on Inuit Education started in 2006. Mary Simon, a former ITK President, launched it. This plan aimed to improve Inuit education. It wanted to make it equal to the rest of Canada. It led to a meeting in the Northwest Territories in 2008.

The strategy's goal is to help Inuit children feel proud of their language and culture. It also wants to increase their opportunities. Less than 25% of Inuit students who start school actually graduate. The strategy focuses on three main areas. First, helping children stay in school. Second, providing education in both Inuit language and one of Canada's official languages. This includes learning materials that fit Inuit culture and history. Third, increasing the number of Inuit teachers and leaders in schools.

Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee

In February 2017, ITK and the Government of Canada created the Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee (ICPC). This committee works on goals that are important to both Inuit and the government. The Prime Minister and the ITK president lead one meeting each year. Other meetings are led by the ITK president and the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations. Other members include government ministers and leaders from Inuit organizations.

The ICPC focuses on many areas. These include land claims, Inuit language, and reconciliation. They also work on education, health, and the environment. Climate change, housing, and economic development are also key areas. To fight climate change, ITK has a national strategy. It focuses on five areas: building skills, health and environment, food systems, infrastructure, and energy. The government has promised money for this plan. In March 2020, they also focused on an action plan. This plan addresses the calls for justice from the National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

Canada Goose Project Atigi

Canada Goose is a Canadian brand that sells winter clothes. In 2019, Canada Goose and ITK worked together on Project Atigi. For this project, 20 Inuit representatives created parka designs. These designs were inspired by traditional Inuit clothing and culture. There will be more collections in the future. ITK chooses the Inuit representatives for these projects.

How ITK is Run

ITK is run by a board of directors and a president. The board includes presidents from four regional Inuit land claims organizations. These are Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, Makivik Corporation, Nunatsiavut Government, and the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation. Each director has one vote. Each organization chooses one director for the board.

A director is removed if they are under 18, declared unable by a court, or bankrupt. There are also three non-voting members on the board. These are the National Inuit Youth Council (NIYC), Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC Canada), and Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada.

The ITK president serves for three years. They can serve more terms if re-elected. To become president, an Inuk person must submit a written request. This request must be signed by at least 20 other Inuit.

The board of ITK manages its activities and affairs. They can borrow money and create security interests. The president attends meetings and carries out the board's decisions. They also oversee ITK's daily management. The president usually lives in Ottawa. The vice-president is the current president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (Canada). They act as president when the president is away. They also support the president. The secretary/treasurer is appointed for one year. They work with the president and vice-president. They are in charge of ITK's finances. The executive director manages ITK's daily operations.

Terry Audla was elected President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami on June 6, 2012. Natan Obed took over from him. Obed was elected on September 17, 2015, in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. He was re-elected for another three-year term in 2018. In 2021, Natan Obed was re-elected without opposition.

Presidents of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

| No. | Name | Term of office |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tagak Curley (founding president) | 1971-1974 |

| 2 | James Arvaluk | 1974-1977 |

| 3 | Michael Amarook | 1977-1978 |

| 4 | Eric Tagoona | 1978-1979 |

| 5 | Micheal Amarook | 1979-1981 |

| 6 | John Amagoalik | 1981-1985 |

| 7 | Rhoda Innuksuk | 1985-1988 |

| 8 | John Amagoalik | 1988-1991 |

| 9 | Rosemarie Kuptana | 1991-1997 |

| 10 | Mary Sillet | 1997-1998 |

| 11 | Okalik Eegeesiak | 1998-2000 |

| 12 | Jose Kusugak | 2000-2006 |

| 13 | Mary Simon | 2006-2012 |

| 14 | Terry Audla | 2012-2015 |

| 15 | Natan Obed | 2015-present |