Inuit culture facts for kids

The Inuit are a group of indigenous people who live in the cold Arctic and subarctic parts of North America. These areas include parts of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. The ancestors of today's Inuit are connected to other groups like the Iñupiat in northern Alaska, the Yupik in Siberia and western Alaska, and the Aleut people from the Aleutian Islands. The Inuit culture is deeply tied to these northern lands.

The word "Eskimo" was once used for Inuit and Yupik people, but it is now less common. Many people consider it an old term that can be disrespectful.

In Canada, various Inuit groups live in different regions. These include the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Northwest Territories, the large Nunavut territory, Nunavik in northern Quebec, and Nunatsiavut in Labrador. These areas, except for one, are sometimes called Inuit Nunangat, which means "Inuit homeland."

The traditional Inuit way of life is perfectly suited for very cold climates. Their main skills for survival were hunting and trapping. They also made special fur clothing to stay warm. Farming was impossible in the vast areas of tundra and icy coasts. Because of this, hunting became the most important part of Inuit culture. They used tools like harpoons and bows and arrows to hunt animals of all sizes. Even today, in modern Inuit communities, you can still see how this 5,000-year history of hunting shaped their lives and allowed them to thrive in the Arctic.

Contents

- Understanding the Name "Inuit"

- Inuit Circumpolar Council: A Global Voice

- A Journey Through Inuit History

- Inuit in Canada: Transition to the 21st Century

- Movies Featuring Inuit Culture

- Images for kids

- See also

Understanding the Name "Inuit"

The word "Inuit" is the name these people use for themselves, and it means "the people." The singular form, referring to one person, is "Inuk."

Long ago, Europeans in North America called the Inuit "Eskimos." However, many Inuit people find this term offensive. One reason is a common belief that in some Algonquian languages, "Eskimo" might mean "eaters of raw meat." Some language experts suggest the word could come from a Cree word meaning "he eats it raw."

Inuit Circumpolar Council: A Global Voice

The Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) is an important international group that represents about 180,000 Inuit and Yupik people. These communities live across the circumpolar region in Alaska (United States), Canada, Greenland (Denmark), and Chukotka, Siberia (Russia).

The ICC first met in 1977. Its main goals are to bring Inuit people from different countries closer together and to protect their rights and interests around the world. The council also works to create policies that keep the Arctic environment safe. They want Inuit people to have a full and active role in the political, economic, and social growth of their regions. In short, the ICC aims to strengthen connections among Arctic peoples and promote their human, cultural, political, and environmental rights.

A Journey Through Inuit History

Scientists believe the ancestors of the Inuit and related groups came from eastern Siberia about 10,000 years ago, arriving in the Bering Sea area.

The Inuit in North America, including Greenland, are descendants of a group called the Thule people. They started in western Alaska around 1000 CE (Common Era). The Thule people spread eastward across the Arctic, eventually replacing an older culture known as the Dorset culture. The Dorset people, called Tuniit in Inuktitut, were known in Inuit stories as powerful giants.

The first Inuit groups, known as Paleo-Eskimos, crossed the Bering Strait around 3000 BCE (Before Common Era). They moved into the northern Canadian Arctic around 2300 BCE, possibly because of climate changes. From there, they slowly followed animal herds across the Arctic to Greenland, forming different nomadic tribes.

Early Paleo-Eskimos faced tough winters in the high Arctic. They lacked some technologies that came later, like advanced boats, dog sleds, and warm houses beyond skin tents. They hunted muskoxen and caribou with bows and arrows and fished with barbed tools. Those near the coast hunted seals, walruses, and smaller whales using harpoons from the shore or sea ice.

The Thule People: Ancestors of Today's Inuit

The Thule culture, which flourished from about 1000 to 1800 CE, represents the direct ancestors of today's Inuit. They originated near the Bering Strait. The Thule people developed many new techniques for hunting and fishing. These advancements greatly changed their way of life.

Thule Innovations and Lifestyle

The Thule people created amazing new tools and methods. They built boats like the kayak (called qajag in Inuktitut), a small boat for hunters, and the umiak, a larger boat used by groups, often women. They also developed new spears and harpoons with weights and floats. These tools allowed them to hunt large animals like whales, which provided valuable food (especially whale skin, rich in vitamin C) and materials for building and heating (whale oil).

The Thule also developed dog sleds for easier travel and built warm igloos that could be entered through a tunnel. These innovations made life more comfortable during the harsh winters. All these changes helped shape new social, religious, and artistic values.

Thule Migrations and Expansion

Around 1000 CE, a warmer climate in North America led to more habitable land in the Arctic. This, along with hunting animals and searching for meteorite iron, encouraged the Thule people to migrate from Alaska into northern Canada and Greenland. They were technologically advanced and, in most areas, integrated with or replaced the Dorset culture. The Dorset culture eventually disappeared around 1000 CE, though some groups survived longer in isolated areas.

The first traces of Thule settlements were found in Thule, Greenland, at a place called Comer's Midden, which is why they are named the Thule people.

Thule Dwellings and Art

Typical Thule homes were built with frameworks of whale jawbones and ribs, anchored in the ground with rocks. Animal hides were stretched over the frame and covered with sod for insulation. For summer hunting trips, they used hide tents.

Thule art was mostly practical, with decorative carvings on everyday tools. They also made small ivory carvings of female figures, water birds, and whales. These artworks often showed a comfortable lifestyle, suggesting they had time to decorate their personal items.

The Thule people also built many Inuksuit, which are stone landmarks piled up to look "like a man." These impressive stone structures still stand today.

Life in the 19th and 20th Centuries

From the 14th century onward, the Arctic experienced a gradual cooling period, known as the "Little Ice Age" (1550-1880). This made life much harder for the Thule people, who depended on hunting. Some regions became depopulated due to migrations or starvation. Traditional life continued mainly in more hospitable areas like southern Baffin Island, Labrador, and southern Greenland.

European Contact and Trade

The 17th century brought European whaling ships to Greenland, leading to big changes. Trade with Europeans became common, and some Inuit intermarried with European-Canadians and European-Americans.

In Canada, early contact with Vikings, explorers, fishermen, and whalers had a more local impact. However, these contacts also brought various diseases that were new to the Inuit, causing many to become ill.

Later, traders, missionaries, and Canadian government officials settled in the Arctic. The Canadian government set up administrative and police stations in the early 1900s. The Hudson's Bay Company also expanded its trade into the "Barren Lands."

The Inuit began hunting animals not just for food and clothing, but also to trade for European goods. Arctic fox fur was especially popular. Through trade, the Inuit acquired items like weapons, ammunition, tobacco, coffee, tea, sugar, and flour. This trade made them more dependent on outside markets and changed their traditional self-sufficient way of life.

Traditional Social Structure and Daily Life

In the 19th century, Inuit society was made up of about 50 groups, each with 200 to 800 members. These groups were loose clans of extended families, including grandparents, parents, and children. This flexible structure helped families survive during times of scarcity.

Hunting provided the Inuit with a balanced diet and materials for clothing, housing, tools, boats, sleds, and art. They used carefully chosen and carved stones for tools like arrowheads and knives. Soapstone, a soft material, was used for oil lamps (qulliqs) and cooking pots.

Plants were rare in the Arctic, so Inuit relied on animal products for vitamins. They ate raw animal foods like muktuk (whale skin and blubber), meat, and fish.

In winter, Inuit lived in igloos or qarmait (half-subterranean houses made of rocks, whale bones, and sod). These homes had a lowered entrance tunnel to keep out cold air and wind. Girls played with string figures inside igloos, learning to sew and sharing stories.

Inuit winter clothing was designed to trap body heat. They used seal and caribou skin, and sometimes polar bear fur in Greenland. Clothes were worn in two loose layers to create a cushion of warm air. Mothers used a special part of their parka (amauti) to carry toddlers.

Nomadic Life in the Early 20th Century

Many elders remember a time, over 60 years ago, when Inuit lived a nomadic life. They moved their camps frequently, following animal herds for food and clothing, sometimes adapting to as many as sixteen seasons.

In summer, most Inuit lived in hide tents, or sometimes canvas tents from the Hudson's Bay Company. The tents were divided into a sleeping area and a cooking/living area. The woman's sleeping place was near the kudlik (oil lamp) for cooking and warmth, and the man's near his hunting tools. Children slept between their parents for warmth. Today, modern portable stoves often replace the kudlik.

In summer, people moved to river estuaries to catch Arctic char and seabird eggs. Inland Inuit relied on caribou for meat, hides, and sinew. Coastal Inuit hunted seals, walruses, narwhals, and belugas. Seal oil was used for lamps, and their skins and sinews for boots (kamik), kayak coverings, and ropes.

In winter, families lived in igloos, sometimes connected by tunnels. They needed specific snow to build them. The layout was similar to tents, with a lowered entrance and an elevated sleeping area to stay warm. Some families built semi-permanent qarmaqs from rocks, whale bones, and sod, using them in winter and tents in summer.

During winter, families gathered more closely. They visited other groups to share news, experiences, and different types of food. Travel in winter was by dog sleds or on foot. In warmer seasons, people used kayaks or larger umiaks (often called "women's boats" for families) and traveled on foot.

Inuit in Canada: Transition to the 21st Century

Major Changes in Living Conditions

Between 1800 and 1950, the lives of Canadian Inuit changed greatly. They had not used money before, but now they became dependent on goods from industrialized countries, like clothing, food, weapons, and tools. Their traditional hunting and trapping could not always provide enough money for this new way of life.

After World War II, the Canadian government became more interested in the Arctic for military defense and natural resources. This led to the building of military and radar stations, which brought new jobs and infrastructure. However, it also caused rapid urbanization, and many communities struggled to adapt. Traditional ways of life were often disrupted without enough support for the transition.

In the late 1940s, challenges increased. The Kivalliq Region faced a quarantine due to serious diseases like polio, and the caribou population declined, threatening food supplies. Many Inuit also faced tuberculosis and had to travel south for treatment. The Canadian government began to provide social benefits and welfare programs. However, in some cases, Inuit families were moved from their traditional hunting grounds to new areas to strengthen Canada's claim to the Arctic.

Traditional Customs and Family Life

Traditionally, the roles of men and women in Inuit families were distinct but complementary. Men were responsible for hunting, fishing, and building homes like igloos and qarmaqs. Women managed household tasks, cared for children, prepared food, cleaned furs, and sewed clothing. However, these roles were not always strict; men needed to know how to sew for clothing repairs, and women needed to know basic hunting and igloo building skills.

When families moved from scattered camps to permanent settlements in the 1950s, these roles began to change. Women found new jobs in healthcare, local administration, and Inuit arts, contributing financially to their families. Today, the division of tasks between Inuit men and women is similar to other parts of Canada. For example, Nellie Cournoyea, an Inuk, was the first female premier of the Northwest Territories.

Pregnancy and Birth Traditions

Traditionally, when a woman became pregnant, it was important to share the news with her family and community. The Inuit believed that special care was needed to ensure the health of the mother and baby. Elders shared traditional wisdom, called pittailiniq, which guided women's activities and diet during pregnancy. For example, women were encouraged to stay physically active and were advised to eat only cooked meat.

Birth was a community event, often assisted by a midwife (Kisuliuq or Sanariak). Midwives were respected women who gained their skills by helping at many births. Women were expected to continue daily chores during early labor and were encouraged to follow their body's natural cues during birth.

Welcoming a Newborn

The arrival of a newborn was a joyful occasion for the entire community. Everyone, including children, would greet the baby. A special person, often the midwife, would determine the baby's gender and become the child's sanaji (for a boy) or arnaliaq (for a girl). This person would have a lifelong role in the child's life, cutting the umbilical cord, providing first clothes, and naming the child.

Naming Customs

The tuqurausiq was a very important naming practice. A child was named after a recently deceased relative or community member. The Inuit believed that the child would then carry the spirit of that person. Family members would even call the child by the name of the deceased, showing them the same respect. This custom continues today, though names might also be English.

Returning to Community Births

For many years, pregnant Inuit women were flown to southern hospitals to give birth. This practice caused cultural challenges, as many felt their children born outside their homeland were not truly Inuit. Starting in the late 1970s, women in Nunavut pushed to bring births back to their communities. They believed that giving birth in their homeland would strengthen families and community bonds.

In 2008, the government of Nunavut passed a law to support midwives, allowing them to provide full prenatal, birth, and postpartum care. Nunavut Arctic College also started a midwifery training program that includes traditional Inuit midwifery knowledge.

Birth centers have opened in Nunavut, such as in Rankin Inlet (1993) and Iqaluit (2007). These centers aim to provide safe, community-based care, reducing the need for women to travel south for birth. The Qikiqtani birth center in Iqaluit, for example, handles many births each year and has a very low cesarean rate.

Death and Remembrance

When Inuit lived as nomads, they did not have special cemeteries. After a person died, their body was washed, wrapped in caribou hide or wool, and placed far out on the tundra, face up. Stones were stacked on top to protect the body from animals. This practice has been observed for centuries, as seen with the Qilakitsoq mummies from 500 years ago.

The Inuit believed the aurora borealis (northern lights) were signals from the spirits of the dead. Some believed that whistling could interact with the lights, but this was also seen as potentially dangerous. In pre-missionary times, newborns were often given the name of a recently deceased relative, allowing ancestors to experience a new life through the child. This custom continues today, even though most Inuit are now Christian.

Since moving to settlements, the dead are buried in cemeteries. Due to the frozen permafrost, graves are not deep and are covered with rocks.

Challenges and Modern Adaptations

The rapid changes in lifestyle presented huge challenges for many Inuit in maintaining their identity and history. These changes led to difficulties in adapting to new ways of life. The Inuit population has grown significantly since the 1960s, reaching over 65,025 people in the 2016 Canadian census.

Modern technology quickly replaced traditional methods. Firearms replaced lances, and snowmobiles (often called Ski-Doo, after an early brand) took the place of dog sleds. All-terrain vehicles (ATVs) also became common for transportation.

The Inuit became consumers, earning money through fishing, hunting, trapping, and creating artwork. Many also work in wage labor or receive social welfare. Government support is often a main source of income.

Adjusting to Modern Society

Adapting to a capitalist way of thinking was a big challenge for the Inuit. They were once independent, but now they found themselves tied to a money-based system. This created new behaviors and sometimes strained family ties. Adjusting to administrative centers organized by Canadian rules was difficult, and some still feel caught between modern culture and their ancestral ways.

The influence of Christian churches in the 20th century also brought major cultural changes. While most Inuit are now Christian, some elements of Shamanism still exist alongside Christian beliefs.

Modern life is often easier for young people, who find new opportunities but also face challenges from "TV culture" and other modern influences. Compulsory education was introduced in the 1950s, replacing traditional learning from parents. Today, basic education is available in almost all settlements. In Nunavut, Inuit languages like Inuinnaqtun or Inuktitut are used for instruction in early school years. Elders also teach traditional knowledge (Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit) about culture and customs.

As part of Canada's assimilation policy, many Inuit children were sent to residential schools. They were taken from their homes and often forbidden to speak their native language, causing communication problems and a loss of traditional skills upon their return. Today, all Inuit communities in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut offer schooling up to grade 12, and colleges like Aurora College and Arctic College provide further education.

Cooperatives: A Path to Success

The establishment of cooperatives, like Arctic Co-operatives Limited, brought great hope. These cooperatives aimed to help Inuit develop economic skills while preserving their traditional culture. They were very successful in combining economic thinking with traditional activities.

Cooperatives engaged in various activities, including providing goods and services like fuel and construction materials, running supermarkets, hotels, and tourism facilities. They also managed fur trade, fishing, and the production of downs and feathers.

A major success for cooperatives was fostering Inuit art and handicrafts. The creation and trade of sculptures made from serpentine, soapstone, and marble, as well as graphics (drawings, lithographs) and tapestries, became very important economically and culturally. This art branch grew significantly, becoming a leading source of income in Inuit regions.

Current Developments and Self-Determination

After World War II, Inuit groups realized that they needed to unite internationally to protect their cultural identity. This led to the "Pan-Eskimo Movement" and the founding of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) in 1977.

The Inuit want to preserve their cultural values while also embracing modern society's progress. They are concerned about environmental threats from resource development but also seek a future with Western standards. They have learned that by working together regionally, they can better influence their living conditions.

Canadian Inuit, like other indigenous peoples, demanded their own territory and government. In 1962, Inuit gained the right to vote federally. In 1976, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami organization first called for a separate territory in northeastern Canada. After over 15 years of talks, the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement was reached. On April 1, 1999, Nunavut was created as a new Canadian territory.

Nunavut has increasing administrative autonomy, and Inuit have significant local control. They hold important administrative positions, including in police, legal, and social welfare offices. Inuktitut is an official government language, alongside English and French.

A key goal for Nunavut's government is to increase its economic output while balancing traditional life with modern challenges. Hunting, trapping, and fishing are mainly for subsistence and don't generate enough income. Revenue from art and handicrafts is important but supports only a limited number of people. Tourism is also growing but has its limits.

The main task for Nunavut's leaders is to blend tradition with modern life. The success of this self-determination model depends on training enough Inuit leaders for the future.

In Quebec, the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement led to the creation of the Kativik Regional Government, giving the Nunavik region greater political autonomy. Residents of Nunavik's 14 settlements now elect their own representatives.

Settling Land Claims

Canada's Arctic policy includes important agreements that settle Inuit land claims. As the Canadian Arctic's mineral resources were developed, conflicts arose over land ownership. The Inuit claimed large areas they had lived on and used for centuries.

In 1984, an agreement with the Inuvialuit (Inuit in the western Arctic) gave them 91,000 square kilometers of land, money, funds for social improvements, hunting rights, and more say in wildlife and environmental protection.

The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement in 1993 was the most comprehensive agreement in Canada. It granted about 17,500 Inuit 350,000 square kilometers of land, monetary compensation, a share of mineral resource profits, hunting rights, and a stronger voice in land and environmental matters.

Land claims were also successfully settled in northern Quebec. In Labrador, Nunatsiavut was created on June 23, 2000, as an Inuit self-government region for about 3,800 Inuit.

Traditional Inuit Culture Today

The Inuit value self-determination. The governments of Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, and Nunatsiavut operate as consensus governments, without political parties.

Preserving Culture and Tradition

The government of Nunavut works hard to preserve Inuit tradition and culture. They are recording and archiving the oral stories of elders about life before settlements, as this knowledge is becoming rarer. The festival leading up to the new year is Quviasukvik, which is also their traditional new year and is held on Christmas.

Contemporary Literature

Inuit culture has a rich heritage of myths and legends, passed down through oral storytelling. Since the Inuit did not have a written language until recently, storytelling was their main form of literature. It brought families together and connected past and present generations.

Today, some Inuit authors write reports, essays, and poems about traditional life or their own experiences. Notable Inuit writers include Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk (who wrote Sanaaq), Markoosie Patsauq, and Tanya Tagaq. Other well-known authors include Peter Irniq, Alootook Ipellie, Michael Kusugak (a children's author), and Zebedee Nungak.

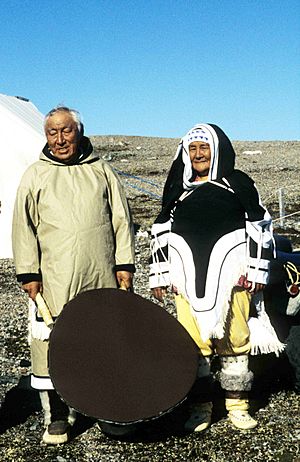

Contemporary Music

Inuit music traditions included "Aya-Yait" songs, used to pass down experiences, and traditional "throat singing" and drum dances for entertainment and rituals. Europeans introduced instruments like the fiddle and accordion, which are still popular. The Inuit also learned the square dance from whalers. In recent decades, a unique Inuit pop music style has emerged. Popular Inuit singers include Susan Aglukark, Tanya Tagaq, Charlie Panigoniak, and Lucie Idlout.

Contemporary Fine Arts

Inuit art and handicrafts became important economic resources in the late 1950s. Today, soapstone sculptures, drawings, tapestries, clothing, ceramics, and dolls provide a livelihood for many Inuit artists, alongside hunting and fishing. This art form has become very significant for the Inuit economy.

Movies Featuring Inuit Culture

- The Way of the Eskimo (1911)

- Nanook of the North (1922)

- Eskimo (1932–33)

- Trial at Fortitude Bay (1994)

- Kikkik (2000)

- Atanarjuat – The Fast Runner (2001)

- Minik (2006)

- The Necessities of Life (2008)

- White Dawn

Images for kids

-

Human remains on a beach near Bathurst Inlet

See also

- Circumpolar peoples

- Disc number – used by the Government of Canada in lieu of surnames

- Eskimo

- Head pull – Inuit game

- Higher education in Nunavut

- Lists of Inuit

- Siberian shamanism, Inuit religion, and Alaska Native religion

- Two-spirit

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |