Inuit clothing facts for kids

Traditional Inuit clothing is a special type of warm clothing. It was historically made from animal hide and fur. Inuit people, who live in the Arctic parts of Canada, Greenland, and the United States, wore these clothes. A basic outfit included a parka, pants, mittens, inner footwear, and outer boots. The most common materials were caribou (reindeer) and seal skins. Sometimes, seabird skins were used too.

Making warm, strong clothing was a very important skill for survival. Women taught this skill to girls, and it could take many years to learn. Preparing the clothing was a long process, taking weeks each year after hunting seasons. The way Inuit made and used their skin clothing was also closely connected to their spiritual beliefs.

Even though Inuit lived across a huge Arctic area, their traditional clothes were very similar. This was because everyone needed protection from the extreme cold. Also, there were only a few types of materials available. Clothes changed slightly based on who wore them (men or women), the season, and the specific Inuit group. Inuit decorated their clothing with fringes, hanging pieces, and colourful designs. Later, they added beadwork when new materials became available through trade.

The Inuit clothing system is similar to the skin clothing of other circumpolar peoples. These include people in Alaska, Siberia, and the Russian Far East. Old evidence suggests this type of clothing began in Siberia around 22,000 BCE. In northern Canada and Greenland, it started around 2500 BCE. When Europeans explored the North American Arctic in the late 1500s, Inuit began to use some European clothes. At the same time, Europeans started studying Inuit clothing. They made drawings, wrote about it, studied how well it worked, and collected pieces for museums.

Today, Inuit life has changed, and fewer people make full outfits of skin clothing. However, since the 1990s, Inuit groups have worked to bring back these traditional skills. They combine old methods with new ones. This has led to a return of traditional Inuit clothing, especially for special events. It has also helped create a unique Inuit fashion style.

Contents

What Inuit People Wore

The main traditional Inuit outfit included a hooded parka, pants, mittens, inner footwear, and outer boots. All these items were made from animal hide and fur. These clothes were quite light, usually weighing only about 3 to 4.5 kilograms. People could add more layers if the weather was colder or if they were doing certain activities.

Even though the basic outfit was similar across all Inuit groups, there were many different styles. These styles often depended on where the clothing was made. For example, the parka alone had many different looks. These included the shape of the hood, how wide the shoulders were, and if it had front or back flaps. Women's parkas also varied in the size and shape of the baby pouch.

The style of clothing could show which group or family someone belonged to. This was seen in the patterns made by different fur colours, the way the garment was cut, and the length of the fur. Sometimes, clothing styles could even tell you a person's age, if they were married, or their family group. The Inuit languages have many words to describe these different clothing items.

This article uses Canadian Inuktitut words for clothing names.

| Body Part | Clothing Name | Inuktitut syllabics | What it is | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torso | Qulittuq | ᖁᓕᑦᑕᖅ | Closed hooded parka, fur outside | Men's outer parka |

| Atigi | ᐊᑎᒋ | Closed hooded parka, fur inside | Men's inner parka | |

| Amauti | ᐊᒪᐅᑎ | Closed parka with a pouch for babies | Women's parka | |

| Hands | Pualuuk | ᐳᐊᓘᒃ | Mitts | For everyone, sometimes double layered |

| Legs | Qarliik | ᖃᕐᓖᒃ | Trousers | Men wore two layers, women one |

| Mirquliik | ᒥᕐᖁᓖᒃ | Stockings | For everyone, sometimes double layered | |

| Feet | Kamiit | ᑲᒦᒃ | Boots | For everyone, length depended on use |

| Tuqtuqutiq | ᑐᖅᑐᖁᑎᖅ | Overshoes | For everyone, worn when needed |

Parkas and Jackets

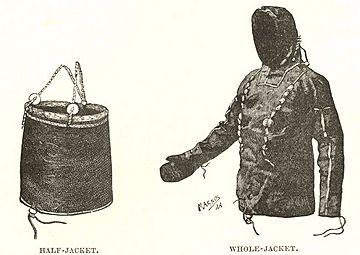

In traditional Inuit culture, men and women had different jobs. Their clothes were made to fit these different roles. Men's outer parkas were called qulittaq, and inner parkas were called atigi. These parkas did not open in the front; you pulled them over your head. Men's parkas usually had straight bottoms with slits and loose shoulders. This allowed hunters to move easily. Loose shoulders also meant a hunter could pull their arms inside the coat for warmth without taking it off. The hood fit closely to protect the head without blocking vision. The back of the outer coat was long. This allowed a hunter to sit on it, staying warm and insulated from the snow while hunting seals or waiting out a storm. Traditional parkas had no pockets. Items were carried in bags or pouches.

Women's parkas are called amauti. They have large pouches called amaut for carrying babies. The baby rests against the mother's bare back inside the pouch, which keeps the baby warm. A belt is tied around the mother's waist outside the amauti. This supports the baby without holding it too tightly. The baby usually sits upright, but can stand up inside the pouch. The roomy garment allows the child to be moved to the front for feeding. It can also be reversed so the child faces the mother to play.

In the western Arctic, another style of women's parka, called the "Mother Hubbard," became popular. It was inspired by a European dress. This Inuit version is a long, full-length cotton dress with a ruffled hem and a fur-trimmed hood. It has a warm lining, often wool or fur, making it suitable for winter. Even though it arrived later, it became a very common traditional women's garment in those areas.

The modern hooded coat, known as a parka or anorak, comes from the Inuit garment. The words "parka" and "anorak" were borrowed from the Aleut and Greenlandic languages.

Pants and Leggings

Both men and women wore trousers called qarliik. In winter, men often wore two pairs of fur trousers to stay warm on long hunting trips. Qarliik reached the waist and were held up by a loose drawstring. Their shape and length depended on the material. Caribou trousers were bell-shaped to trap warm air, while seal or polar bear trousers were usually straight-legged. In some areas, people also wore leggings with attached feet, similar to long socks.

Women's qarliik were generally shaped like men's. However, women wore fewer layers overall because they usually did not spend as much time outdoors in winter. In some areas, women wore short, thigh-length trousers with separate leggings instead of full-length pants. Some Inuit groups wore baggy leggings sewn to their boots for long journeys. These wide leggings could also be used to warm food or store small items.

Footwear

Traditional Inuit footwear could have up to five layers of socks, boots, and overboots. This depended on the weather and ground conditions. These items were almost always made from caribou or sealskin. Today, boots are sometimes made with heavy fabric like canvas or denim. The first layer was stockings with fur facing inwards. The second was short socks, and the third was another set of stockings with fur facing outwards.

The fourth layer was the boots, called kamiit or mukluks. The most unique part of kamiit is their soles. They are made from a single piece of skin that wraps up the side of the foot and is sewn to the top part. They are loose-fitting to allow for more layers and can be tightened at the top or ankles with a drawstring. Kamiit could be covered with tuqtuqutiq, which are short, thick-soled overshoes. These gave extra warmth to the feet and could be worn indoors as slippers while the kamiit dried. Men often had several pairs of boots so they could dry out between uses, which prevented rot and made them last longer.

In summer, waterproof boots were worn instead of fur boots. These were usually made from sealskin with the fur removed. To help with grip on icy ground, boot soles could have pleats, strips of dehaired seal skin, or fur pointing forward. Boot height varied depending on the activity. Sealskin boots could be thigh-high or chest-high for wading into water, like modern waders.

Accessories

Most upper garments had a hood built in, so separate head coverings were not needed. The hoods of the Iñupiat people in northern Alaska are known for their distinct "sunburst" ruff around the face. This was made from long fur from wolves, dogs, or wolverines. Some groups, like the Kalaallit of Greenland, wore separate hats instead of hoods. Many modern Canadian Inuit wear a cap under their hood for extra warmth in winter. In summer, when it's warmer and there are mosquitoes, the hood is not used. Instead, a cap is worn with a scarf to cover the neck and face from insects.

Inuit mitts are called pualuuk and are usually worn in a single layer. If needed, two layers could be used, but this made it harder to move fingers. Most mitts were made of caribou skin. Sealskin was used for wet conditions, and bear fur was preferred for icing sled runners because it doesn't shed when wet. The palm of the mitt could be made of skin with the fur removed for better grip. Sometimes, a cord was attached to the mitts and worn across the shoulders to prevent them from getting lost.

Belts were usually simple strips of skin with the hair removed. They had many uses. The qaksun-gauti belt held the child in the amauti. Belts tied at the waist could keep parkas tight against the wind and hold small items. In emergencies, a belt could be used to fix broken equipment. Some belts were decorated with beads or carved pieces.

Inuit groups who regularly used kayaks developed special clothing to keep water out of the kayak's cockpit. In Greenlandic, these are called the akuilisaq (now called a spray skirt) and the watertight tuilik jacket. Both prevented water from entering the kayak. The tuilik also allowed the kayaker to roll their kayak without getting wet inside.

In the Arctic spring and summer, bright sunlight reflecting off the snow can cause snow blindness. To prevent this, Inuit created ilgaak or snow goggles. These eyewear items reduce glare but still allow a good field of view. Ilgaak are traditionally made from bone or driftwood. They are carved to fit the face and have narrow horizontal slits that let in only a small amount of light.

Children's Clothes

Inuit babies wore very little clothing, as they were usually held close to their mother in the amauti. Any clothing they did wear, like a small jacket, cap, mittens, or socks, was made from the thinnest skins available. These included skins from fetal or newborn caribou, crows, or marmots.

Children's clothing was similar to adult clothing but made from softer materials. These included caribou fawn, fox skin, or rabbit. Once children could walk, they wore a one-piece suit called an atajuq. This garment had attached feet and often mittens. Unlike adult trousers, it opened at the bottom to make it easier for the child to use the bathroom. Many of these suits had separate caps that could be tied on so they wouldn't get lost. The hood shape and decorations on these suits showed if they were for a boy or a girl.

As children grew older, they gradually started wearing more adult-like clothes. Older children wore outfits with separate parkas and trousers. However, boots were usually sewn directly to the trousers. Girls' amauti often had small baby pouches. Girls sometimes carried younger siblings in them to help their mothers.

Materials Used for Clothing

The Arctic climate is not good for growing plants or raising animals that produce most fabrics. So, Inuit used fur and skins from local animals. The most common materials for Inuit clothing were caribou and seal skins. Caribou was preferred for general use. In the past, seabird skins were also important, but they are rare now. Other animals used included bears, dogs, foxes, ground squirrels, moose, muskoxen, muskrats, whales, wolverines, and wolves. The use of these animals depended on the location and season. Other skins often had problems like being fragile, heavy, or shedding hair.

Traditionally, Inuit used as much of the animal as possible. Each part of the hide had a specific use. Tendons were used to make strong threads called sinew thread or ivalu for sewing. Feathers were used for decoration. Bones, beaks, teeth, claws, and antlers were carved into tools or decorations. Intestine from seals and walruses was used to make waterproof jackets for bad weather.

Because skins were valuable, old or worn-out clothing was not thrown away. It was reused as bedding or work clothes, or taken apart to repair newer garments. In very difficult times, like when caribou hunting failed, scraps of old clothes could be sewn together to make new ones. These were not as warm or strong, though.

Inuit groups shared clothing designs, materials, and styles through trade. There is evidence that ancient Inuit gathered at large trade fairs to exchange materials and finished goods. This trade network covered about 3000 kilometers of Arctic land. They also learned from and used ideas and materials from other Arctic peoples. These included people from Siberia, Scandinavia, and other North American indigenous groups.

Caribou and Seal Skins

The hide of the barren-ground caribou was the most important material for all kinds of clothing. It was easy to find, useful for many things, and very warm when the fur was left on. Caribou fur has two layers that trap air, which is then warmed by body heat. The skin itself is thin and flexible, making it light. Caribou had to be hunted at specific times to get the best quality skins. If hunted too early in spring, the hide would have holes or lose hair. If hunted too late in fall, the skin would be too thick and heavy. Each part of the hide was used for specific purposes. For example, tough leg skins were used for durable items. Caribou fur sheds a lot when wet, so it was not good for wet-weather clothes.

The hide of Arctic seals is light and water-repellent. This makes it perfect for single-layer clothing in wet summer weather. All year round, it was used for water-based activities like kayaking and fishing, as well as for boots and mittens. Seal hide lets sweat evaporate, which is great for boots. The ringed seal and bearded seal are most commonly used for clothing. This is because they are plentiful and found in many places.

Bird Skins

Inuit groups across the Arctic used bird skins, especially where larger animals like caribou were less common. Bird skin, feet, and bones were used for clothes, tools, and decorations. Bird skins have some downsides compared to caribou skin. Their feathers make them bulky, and they are less durable. Also, their small size means many birds are needed for a large garment. More than two dozen bird species were used, including auks, cormorants, crows, eider ducks, gooses, and swans. The toughest skins came from diving birds.

The Qikirtamiut of the Belcher Islands used eider duck as their main clothing material because there were no caribou on the islands. They knew a lot about how different eider duck skins worked based on the bird's age, gender, and season. For example, tough skins from adult male ducks were used for hunter's clothes. Flexible skins from young ducks were used for children's clothing.

Other Natural Materials

Polar bear fur was a major material for winter clothes for Greenlandic Inuit in the 1800s. Like caribou fur, polar bear fur has two layers and is great at trapping heat and resisting water. The long guard hairs of dogs, wolves, and wolverines were preferred for trimming hoods and mittens. Arctic fox fur was also used for trim, hunting caps, and the inside of socks. In some areas, women's clothing was made of fox hides to keep them warm while feeding babies.

Adult musk-ox hide is too heavy for most clothes. However, it was used for mittens and summer caps, as its long hairs kept mosquitoes away. It was also good for bedding. In places where large animals were rare, like Alaska and Greenland, skins of small animals like marmots and Arctic ground squirrels were sewn together to make parkas.

The skin of cetaceans like beluga whales and narwhals was sometimes used for boot soles. Whale sinew, especially from the narwhal, was valued for its length and strength as thread. Tusks from narwhal and walrus provided ivory. This was used for sewing tools, clothing fasteners, and ornaments.

Dried grass and moss were used for insulation and to absorb moisture. They could be placed inside stockings to absorb sweat from feet. They could also be put at the bottom of the amaut for babies, similar to a diaper.

Fabric and Man-Made Materials

Starting in the late 1500s, contact with non-Inuit people began to change Inuit clothing. Traders and explorers brought new items like metal tools, beads, and fabric. These began to be used in traditional clothing. For example, imported duffel cloth was useful for boot and mitt liners. Quilted fabric was used to line parkas. Sewing machines arrived around the 1850s, making it easier to produce clothes from imported cloth.

While men often adopted ready-made European clothes, Inuit women used purchased cloth to make garments that fit their needs. In the mid-1800s, the Alaskan Iñupiat started using colorful imported fabrics like drill and calico. They made over-parkas to protect their caribou clothes from dirt and snow. The longer women's version became known as the Mother Hubbard parka. These fabric garments were valued because they were simpler to make than skin clothing. Their new materials also showed wealth and status.

Even with new materials, the basic design of traditional skin clothing stayed the same. Inuit chose foreign items that made sewing easier (like metal needles) or looked good (like beads and dyed cloth). They avoided things that didn't work well, like metal fasteners (which could freeze) and synthetic fabrics (which absorb sweat).

How Clothing Was Made and Cared For

Historically, women were in charge of every step of making clothes. This included preparing skins and sewing the final garments. These skills were passed down in families from grandmothers and mothers to their daughters. Learning these skills fully could take until a woman was in her mid-thirties. Young girls practiced by making dolls and doll clothes from hide scraps. Then they moved on to small items like mittens for actual use.

To ensure the family's survival, clothes had to be well-made and cared for. Poorly made clothing would lose heat. This made it harder for people to do important tasks like hunting and traveling. It could also lead to health problems like hypothermia or frostbite. For this reason, most garments, especially boots, were made from as few pieces as possible. This reduced the number of seams, which helped keep heat in.

Making new clothes happened yearly after the hunting seasons. Caribou were hunted in late summer and autumn. Sea mammals like seals were hunted from December to May. Making clothes was a big job for the whole community. Men butchered animals and stored food. Women processed hides and sewed clothes. The sewing period after hunting could last two to four weeks. It could take 300 hours just to prepare the twenty caribou hides needed for a family of five to have two sets of clothes. Another 225 hours were needed to cut and sew the garments.

Tools Used for Sewing

Inuit seamstresses traditionally used tools made from animal materials like bone, baleen, antler, and ivory. These included the ulu (woman's knife), knife sharpener, scrapers, needle, awl, thimble, and needlecase. Uluit were especially important tools. They were often buried with their owner. Wood and stone were also used to make uluit. Sometimes, meteoric iron or copper was hammered into blades.

After contact with non-Inuit explorers, Inuit started using sheet tin, brass, iron, and steel. They also adopted steel sewing needles, which were stronger than bone needles. Europeans also brought scissors, but Inuit didn't use them much. Scissors don't cut furry hides as cleanly as sharp knives. Today, many tools are bought or handmade from available materials. For example, uluit are made from saw blades with handles from plastic or scrap wood.

Preparing Animal Hides

The first step was taking the skin off the animal after a successful hunt. Hunters usually cut the skin so it could be removed in one piece. Skinning a caribou could take an experienced hunter up to an hour. While men butchered caribou, women mostly butchered seals.

After removing the skin, hides were dried on wooden frames. Then, they were laid on knees or a scraping platform. Women scraped off fat and other tissues with an ulu until the hide was soft and flexible. Most skins were processed similarly. Oily skins like seal and polar bear sometimes needed an extra step of degreasing by dragging them across gravel or washing with soap. If the hide had blood, rubbing with snow or soaking in cold water could remove the stain.

Sometimes, the fur needed to be removed for items like boot soles. This was usually done with an ulu. The hide was repeatedly scraped, stretched, chewed, rubbed, wrung, folded, soaked, and even stamped on to make it softer for sewing. This softening process could involve up to twelve steps. Poorly processed hides would stiffen or rot, so correct preparation was vital for good clothing.

Sewing the Clothes

Once the hide was ready, the process of making each piece began. The first step was measuring, which was very detailed because each garment was custom-made. No standard sewing patterns were used. Older garments were sometimes used as models. Traditionally, measurements were done by eye and hand. Today, some seamstresses make paper patterns after hand and eye measurements.

The skins were marked for cutting. Traditionally, this was done by biting or pinching, or with a sharp tool. Today, ink pens may be used. The direction of the fur was considered when marking. Most garments had fur flowing from top to bottom. Once marked, the pieces were cut using the ulu. Care was taken not to stretch the skin or damage the fur. Adjustments were made during cutting if needed. Marking and cutting one amauti could take an experienced seamstress a whole hour. Up to forty pieces might be cut for complex garments, but most used around ten.

After the seamstress was happy with the size and shape of each piece, they were sewn together. A good fit was important for comfort. Traditionally, Inuit seamstresses used thread made from sinew, called ivalu. Modern seamstresses usually use cotton, linen, or synthetic threads. These are easier to find and work with, but less waterproof than ivalu.

Tight, high-quality seams were essential to keep out cold air and moisture. Four main stitches were used: the overcast stitch, the tuck or gathering stitch, the running stitch, and the waterproof stitch or ilujjiniq. The waterproof stitch is a unique Inuit invention. It was mostly used on boots and mitts. Two lines of stitching made one waterproof seam. The needle never fully went through both skins at the same time. Ivalu swells when wet, filling the needle holes and making the seam waterproof.

Caring for Clothing

Once made, Inuit skin clothing must be cared for properly. Otherwise, it will become stiff, lose hair, or rot. Warmth and moisture are the biggest risks, as they help bacteria grow. If the garment gets dirty with grease or blood, the stain must be rubbed with snow and beaten out quickly. Wearing clean clothes for a hunt was also a sign of respect for animal spirits.

Historically, Inuit used two main tools to keep their clothes dry and cold. The first was the tiluqtut, or snow beater. This was a stiff tool made of bone, ivory, or wood. It was used to beat snow and ice off clothes before entering the home. The second was the innitait, or drying rack. Once inside, clothes were laid over the rack near a heat source to dry slowly. All clothing, especially footwear, was checked daily for damage and repaired right away. Boots were chewed, stretched, or rubbed to keep them durable and comfortable. While women mainly sewed new clothes, both men and women learned to repair clothing. They carried sewing kits for emergency repairs while traveling.

Key Ideas Behind Inuit Clothing

Experts on Inuit clothing point out five main ideas common to all Arctic clothing. These ideas are needed because of the challenges of living in polar environments: insulation, controlling sweat, waterproofing, being practical, and being durable. Other researchers agree on similar principles, focusing on warmth, managing moisture, and sturdiness.

- Staying Warm: Clothes worn in the Arctic must be very warm, especially in winter. During the polar night, the sun never rises, and temperatures can drop below -40°C for weeks or months. Inuit garments were designed to provide thermal insulation in several ways. Caribou fur is excellent because its hollow hairs trap warmth. The air trapped between hairs also holds heat. Each garment was custom-made to fit the wearer's body using special techniques. Clothes were generally bell-shaped to keep warm air inside. Openings were kept small to prevent heat loss. However, if someone got too hot, the hood could be loosened to let heat out. Long, strong hairs from wolves, dogs, or wolverines were used for hood trim. This reduced wind on the face. Layers were made to overlap, stopping drafts. In warmer spring and summer weather, only one layer of clothing was needed. In harsher winter temperatures, both men and women wore two upper-body layers. The inner layer had fur against the skin for warmth, and the outer layer had fur facing outward.

- Controlling Moisture: Perspiration can build up moisture in closed clothes. This moisture must be managed for comfort and safety. The carefully designed layers of traditional clothing allowed fresh air to move through the outfit during physical activity. This removed air full of sweat, keeping both the clothes and body dry. Also, animal skin is somewhat porous and lets some moisture evaporate. When temperatures are low enough for moisture to freeze, it forms frost crystals on the fur. These can be brushed or beaten away. Fur ruffs on hoods collect moisture from breath. When it freezes, it can be brushed off. For footwear, animal skin controls condensation better than materials like rubber or plastic. It lets moisture escape, keeping feet drier and warmer longer. Unlike skin and fur, woven fabrics like wool absorb moisture and hold it against the body. In freezing temperatures, this causes discomfort, limits movement, and can lead to dangerous heat loss.

- Keeping Dry: Making clothes waterproof was very important for Inuit, especially in the wetter summer weather. The skin of marine mammals like seals naturally sheds water. It is also lightweight and breathable. This makes it very useful for this type of clothing. Before man-made waterproof materials, seal or walrus intestine was commonly used for raincoats and other wet-weather gear. Skilled sewing with sinews allowed for waterproof seams, which were especially useful for footwear.

- Being Practical: Clothes were made to be practical and help the wearer do their work efficiently. Since Inuit traditionally had different jobs for men and women, clothes were made in different styles for each. For example, a man's hunting coat had extra room in the shoulders for free movement. It also allowed him to pull his arms inside for warmth. The long back flap kept the hunter's back covered when crouching. The amauti was made with a large back pouch for carrying babies. For both men's and women's clothing, special cuts allowed parkas to be put on quickly. Hoods were made to provide warmth while keeping a good peripheral vision.

- Being Strong: Inuit clothing needed to be extremely durable. Making skin clothing was a lot of work and custom-made. The materials were only available seasonally. So, badly damaged clothes were not easy to replace. To make them last longer, seams were placed to reduce stress on the skins. For example, on the parka, the shoulder seam is dropped off the shoulder. On trousers, seams are placed off the side of the legs. Different cuts of skin were used based on their qualities. Tougher skin from animal legs was used for mitts and boots, which needed to be strong. More flexible skin from the animal's shoulder was used for a jacket's shoulder, which needed to bend. Fasteners and closures were kept to a minimum to reduce the need for repairs. Rips or tears would make the garment less warm and less able to control moisture. So, they were repaired as soon as possible, even out in the field if necessary.

Decorations and Designs

Historically, Inuit added beauty to their clothing with ornamental trim and inlay, dyes, and other coloring methods. They also used decorative attachments like pendants and beads, and design patterns. They adopted new techniques and materials as they came into contact with other cultures. The many techniques Inuit developed allowed for a lot of personal expression in how clothes looked.

Traditionally, trim and inlays were made of fur and skin. Differences in fur direction, length, texture, and color created visual contrast. Generally, women's parkas had much more decoration than men's. Men's parkas sometimes had special markings on the shoulders to show the strength of their arms. In the past, markings on the forearms of amauti reminded people of women's skill in sewing. Inuit groups along the west coast of Hudson Bay used narrow inlays of white fur that looked like women's traditional tattoo designs.

Starting in the 1890s, the Alaskan Iñupiat began to use detailed decorative trim on almost all their clothes. These often had bands of geometric patterns called qupak. When traders brought colorful fabric trim, the Iñupiat added pieces of it to their qupak. When this style spread east into Canada, it was called "delta trim." The Kalaallit of Greenland are known for a decorative trim called avittat, or skin embroidery. Tiny pieces of dyed skin are appliquéd into a mosaic so fine it looks like embroidery.

Some skins were colored or bleached. Dye was used to color both skins and fur. Shades of red, black, brown, and yellow were made from minerals like ochre. These were crushed and mixed with seal oil. Plant-based dyes were also available in some areas. Alder bark gave a red-brown shade, and spruce produced red. The dyeing process also made boots more water-repellent. Skins could also be tanned with smoke to make them brown. Or, they could be left outside in the sun to bleach them white. Today, some Inuit use commercial fabric dye or acrylic paint to color their garments.

Many Inuit groups used attachments like fringes, pendants, and beads to decorate their clothes. Fringing on caribou garments was practical as well as decorative. It could be interlocked between layers to keep wind out. It also weighed down the edges of garments to stop them from curling up. Pendants were made from all kinds of materials. Traditionally, soapstone, animal bone, and teeth were common. After European contact, items like coins and bullet casings were used as decorations.

Inuit clothing often uses motifs, which are figures or patterns in the design. In traditional skin clothing, these are added with contrasting inserts, beadwork, embroidery, or dyeing. The roots of these designs go back to the Paleolithic era. Later designs were more complex, including scrolls, heart shapes, and plant motifs. Some believe these came from contact with First Nations peoples. There are even examples of beadwork from the early 1900s that show complex images like faces and sailing ships.

Since the 1950s and 1960s, the designs on fur inserts for kamiit became more detailed. By the 1980s, they included designs from modern culture. These included animals, flowers, logos, letters, hockey team names, and even snowmobile brand names. Women's designs were traditionally placed horizontally around the top of the boot. Men's motifs were placed vertically down the boot shaft.

Beadwork

Beadwork was usually for women's clothing. Before European contact, beads were made from amber, stone, tooth, and ivory. Starting in the 1700s, European traders brought trade beads. These were colorful, valuable glass beads used for decoration or trade. The Inuit called these beads sapangaq ("precious stone").

Access to trade beads grew a lot in the 1860s. By the early 1900s, many Inuit groups had developed unique and detailed beadwork styles. Strung seed beads were used as fringe or sewn directly onto the hide. Some beadwork was put on skin panels. These panels could be removed from old clothes and sewn onto new ones. Such panels were sometimes passed down through families. In the eastern Arctic, long strings of beads in horizontal bars were draped across the chest. In the central Arctic, beads were placed on parkas where fur insets and skin fringes used to be. Some of these patterns looked like traditional tattoo designs. Elaborately beaded amauti can take weeks or months to make. Because of the hard work, few seamstresses today make detailed beaded panels by hand. Some buy pre-made beaded pieces from fabric stores.

Culture and Identity

The whole process of making and wearing traditional clothing was deeply connected to Inuit spiritual beliefs. Hunting was seen as a sacred act. It was important to show respect and thanks to the animals killed. This would ensure they returned for the next hunting season. Wearing clean, well-made clothing while hunting was important. It showed respect for the animal spirits. Some groups left small gifts at the kill site. Others thanked the animal's spirit directly. Sharing meat from a hunt pleased the animal's spirit and showed thanks.

Special practices existed for polar bears, which were seen as very powerful animals. It was believed that polar bear spirits stayed in the skin for several days after death. When these skins were hung to dry, useful tools were hung around them. When the bear's spirit left, it took the spirits of the tools with it for the afterlife.

For many Inuit groups, the timing of sewing was guided by spiritual rules. Traditionally, women never started sewing until hunting was completely finished. This allowed the community to focus only on the hunt. The goddess Sedna, who ruled the ocean and its animals, disliked caribou. So, it was forbidden to sew sealskin clothing at the same time as caribou clothing. Sealskin clothing had to be finished in spring before the caribou hunt. Caribou clothing had to be finished in fall before hunting seals and walruses.

Many groups also had clothing rules related to death. A baby whose older siblings had died might wear clothes made from a mix of caribou and sealskin. This was to hide the child from evil spirits. Relatives of a deceased person might not be allowed to work on clothing for a certain time after a death. Deceased adults were dressed in their clothes and wrapped in skins. Their remaining clothing was discarded or left at the grave site. Their tools – sewing tools for women and hunting tools for men – were left with them.

Wearing skin clothing traditionally created a spiritual connection between the wearer and the animals. This pleased the animal's spirit, and it would return to be hunted next season. Skin clothing was also thought to give the wearer the animal's traits, like strength, speed, and protection from cold. Making the garment look like the animal made this connection stronger. For example, animal ears were often left on parka hoods to give the hunter good hearing. Contrasting light and dark fur patterns were placed to copy the animal's natural markings. The Copper Inuit used a design like a wolf's tail on the back of their parkas. This referred to the wolf, a natural predator of the caribou.

Amulets made of skin and animal parts were worn for protection and good luck. They were believed to give the wearer the powers of the animal or spirit. Children were thought to be vulnerable and needed the most protection. So, their clothing had many protective amulets. Both the material of the amulet and its place on the body were spiritually important. Hunters might wear tiny model boots to ensure their own boots would last. Weasel skins sewn to the back of the parka gave speed and cleverness. For women, ermine skins gave energy, while loon skins helped with music and dancing. The rattling of ornaments like bird beaks was thought to scare away evil spirits.

Special Occasion Clothing

Besides everyday clothes, many Inuit had special clothing for dancing or other ceremonies. The detailed striped and fringed dance clothing of the Copper Inuit is well-known and kept in museums. Dance parkas usually didn't have hoods. Instead, special dancing caps were worn. These caps had bird beaks sewn on, like from loons and thick-billed murres. This was to bring the animals' vision and speed. White stoat skins were also used to bring the animal's cleverness and ability to hide in snow. Dance clothing was closely related to shamanistic clothing, with designs that referred to the spiritual world.

Inuit shamans, called angakkuq, usually wore clothes similar to other people. But their clothes had unique accessories or designs to show their spiritual status. The detailed parka of the angakkuq Qingailisaq, inspired by spiritual visions, is an example.

Shamans from groups that hunted albino caribou might have parkas with inverted colors. They would be white for the main garment and brown for the decorations. The fur used for a shaman's belt was white. The belts themselves were decorated with amulets, colored cloth, and tools. These often represented important events in the shaman's life. Mittens and gloves were important parts of shamanic rituals. They were thought to protect the hands and remind the shaman of their human side. Using stoat skins for a shaman's clothing brought the animal's intelligence and cunning. Fox or wolf foot-bones brought running speed and endurance.

Traditional ceremonial and shamanic clothing also included masks made of wood and skin. These were used to call upon supernatural abilities. However, this practice mostly stopped after Christian missionaries arrived. While Alaskan religious masks were often elaborate, those of the Canadian Inuit were simpler.

Clothing and Identity

Inuit clothing was traditionally made in different styles for men and women. This was usually for practical reasons, but sometimes for symbolic ones. For example, the shape of the kiniq, the front flap of a woman's parka, was a symbolic reference to childbirth.

Today, making and using traditional skin clothing is increasingly important. It is a visual sign of a unique Inuit identity. Taking part in traditional cultural practices, including sewing clothes, is strongly linked to happiness and well-being for Inuit families and communities. Wearing skin clothing can show one's connection to Inuit culture in general or to a specific group. Decorated kamiit (boots) are seen as an important symbol of Inuit identity and a unique female art form. The amauti is also a symbol of Inuit women and mothers. Sewing clothing is closely connected to motherhood in Inuit culture.

History of Inuit Clothing

The history of Inuit clothing goes back a very long time. Evidence shows that the basic clothing structure has changed little over centuries. The clothing systems of all Arctic indigenous peoples are similar. Tools and carved figures suggest these systems were used in Siberia as early as 22,000 BCE. In Canada and Greenland, they were used as early as 2500 BCE. Sometimes, pieces of old garments are found at archaeological sites. These mostly date from the Thule culture era (about 1000 to 1600 CE). Examples include the fully dressed mummies found at Qilakitsoq in 1972. The structure of these old clothes is very similar to garments from the 1600s to mid-1900s. This confirms that Inuit clothing construction has been very consistent.

Starting in the late 1500s, contact with non-Inuit traders and explorers began to change Inuit clothing. Imported tools and fabrics became part of the traditional clothing system. Sometimes, ready-made fabric clothes replaced traditional ones. The use of fabric clothes was often encouraged by outsiders. Missionaries thought traditional Inuit garments were inappropriate. Traders offered incentives for Inuit to sell their furs instead of using them for clothing. Inuit also adopted fabric clothes for their own convenience, especially men who worked on whaling ships. These voluntary changes often led to the decline of traditional styles. Using manufactured clothing became a sign of wealth and status.

In the early 1900s, more cultural assimilation and modernization led to less production of traditional skin garments for everyday use. The introduction of the Canadian Indian residential school system in northern Canada stopped the traditional way of elders passing down knowledge to younger generations. Even after these schools declined, most day schools did not teach Inuit culture until the 1980s.

Demand for skin garments decreased as lifestyles changed. Manufactured clothing became more available and easier to care for. Overhunting reduced many caribou herds. Opposition to seal hunting from the animal rights movement caused the market for seal pelts to crash. This led to a drop in hunting as a main job. Less demand meant fewer people kept their sewing skills, and even fewer passed them on. By the mid-1990s, the skills to make Inuit skin clothing were almost lost.

Since then, Inuit groups have worked hard to bring traditional sewing skills into modern Inuit culture. Cultural material is now taught in many northern schools and cultural programs. Sewing is now seen as a way to connect with Inuit culture. Using modern techniques and buying materials commercially reduces the time and effort needed. This makes it easier for more people to learn. While full outfits of traditional skin clothing are not common for daily wear, they are still seen in winter and on special occasions.

Many Inuit seamstresses today use modern materials to make traditionally styled garments, especially amauti. Since the 1990s, some seamstresses have started creating fashionable garments to sell. This supports modern Inuit fashion as its own style within the larger indigenous American fashion movement. As Inuit clothing interacts more with the fashion industry, Inuit groups are concerned about protecting their heritage from cultural appropriation.

Studying Inuit Clothing

There is a long history of research on Inuit clothing across many fields. Since Europeans first met Inuit in the 1400s, documentation and research on Inuit clothing has included art, academic writing, studies of how well it works, and collecting items for museums.

Historically, European images of Inuit came from Inuit people who traveled to Europe (willingly or as captives). They also came from clothing brought to museums by explorers and from written travel accounts. The earliest images were printed after an Inuit mother and child from Labrador were brought to Europe in 1566. Other paintings and engravings of Inuit and their clothing were made over the centuries. In the 1800s, photography allowed more images of Inuit clothing to be shared, especially in illustrated magazines.

From the 1700s to the mid-1900s, explorers, missionaries, and academics described the Inuit clothing system in their writings. After a decline in the 1940s, serious study of Inuit clothing picked up again in the 1980s. At that time, the focus shifted to detailed studies of specific Inuit and Arctic groups. It also included working with Inuit communities. Inuit clothing has also been studied a lot for how well it works as cold-weather clothing, especially compared to man-made materials.

Many museums, especially in Canada, Denmark, the United Kingdom, and the United States, have large collections of historical Inuit garments. These were often collected during Arctic explorations in the 1800s and early 1900s. The British Museum in London has some of the world's oldest surviving Inuit fur clothing. The collection at the National Museum of Denmark is one of the largest in the world.

Images for kids

-

Niviatsinaq, a companion of George Comer, in her detailed beaded parka, around 1903–1904.

-

Women's qarlikallaak, or short trousers from Greenland, collected by Robert Peary by 1908.

-

A woman's Copper Inuit parka in the traditional style with exaggerated shoulders, at the Peabody Museum, acquired 1920–1921.

-

A pair of wet-weather kamiit boots and tools for sewing them. Notice the wrap-around sole, seam location, and lack of laces. From Ungava, 1989.

-

Contemporary men's dress shoes made with undyed ringed seal fur, by Nicole Camphaug, 2021.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |