Iñupiat facts for kids

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 20,709 (2015) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| North and northwest Alaska (United States) | |

| Languages | |

| English, Iñupiaq Russian |

|

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Animism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Inuit, Yupik |

The Iñupiat are a group of Alaska Natives. Their traditional lands stretch from Norton Sound on the Bering Sea up to the northern border with Canada. Some Iñupiat believe they were the first people in the Kauwerak area.

Today, there are 34 Iñupiat villages. These include seven villages in the North Slope Borough, eleven in Northwest Arctic Borough, and sixteen villages connected to the Bering Straits Regional Corporation.

Contents

Understanding the Name Iñupiat

The word Iñupiat means "real people." It is the way the people refer to themselves.

- Iñupiat is used when talking about more than one person (plural).

- Iñupiaq is used for one person (singular). It also refers to their language.

- Iñupiak is used when talking about two people (dual).

Iñupiat Groups

The Iñupiat people are made up of different communities:

- Bering Strait Inupiat

- Nunamiut

- Kotzebue Sound Inupiat

- North Alaska Coast Inupiat (Taġiuġmiut, meaning "people of the sea," or Siḷaliñiġmiut)

Regional Corporations

In 1971, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act created thirteen Alaskan Native Regional Corporations. These corporations help Native Alaskans by providing services to their members, who are called "shareholders."

Sometimes, these corporations face challenges. For example, making money from oil or other resources can conflict with the traditional Iñupiat way of life, which depends on healthy ecosystems.

Three of these regional corporations are in Iñupiat lands:

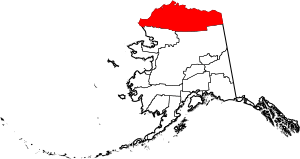

- Arctic Slope Regional Corporation

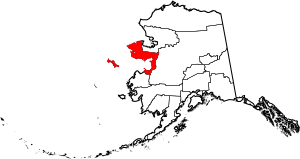

- Bering Straits Native Corporation

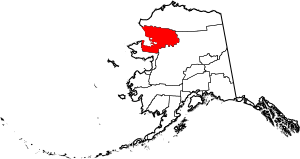

- NANA Regional Corporation

Tribal Governments

Before colonization, Iñupiat people had their own ways of governing themselves. Even after Alaska became part of the U.S., Iñupiat communities continued to show their self-rule.

The U.S. government now recognizes Tribal governments. This means tribes have some control over their own affairs. In 1993, the federal government officially recognized Alaskan Native tribes. This allowed tribes to work with the government to manage programs that help Native people directly.

Across Iñupiat lands, there are different tribal governments. They vary in how they are set up and the services they offer. These services often focus on the well-being of the communities. They can include education, housing, and supporting families and cultural connections.

Languages

The Inuit people and their language stretch across the northern parts of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. In Northern Alaska, the Inuit language is called Iñupiaq.

There are four main Iñupiaq dialects in Alaska: North Slope, Malimiut, Bering Straits, and Qawiaraq. In the past, these dialects were widely spoken. However, due to harsh efforts to make Native people adopt American culture, especially in American Indian boarding schools, many were punished for speaking their language.

Today, only about 2,000 of the 24,500 Iñupiat people can speak their Native language.

Many groups are now working to bring back Alaskan Native languages and ways of life.

- In Kotzebue, the Nikaitchuat Ilisagviat school was started in 1998. It teaches children in Iñupiaq. Its goal is to help students learn about their Iñupiaq identity and culture.

- June Nelson Elementary school in Kotzebue is also adding more Iñupiat language and culture to its lessons.

- Nome Elementary School in Nome plans to start an Iñupiaq language program.

- The University of Alaska system offers many Iñupiaq language courses. For example, the University of Alaska Fairbanks has an online course for beginners. The University of Alaska Anchorage offers several levels of language classes.

Since 2017, Iñupiat language learners have organized Iḷisaqativut. This is a two-week intensive language program held in different Iñupiat communities.

Kawerak, a group from the Bering Strait region, has created a language dictionary. It includes terms from Iñupiaq, English, and other Native languages.

Some Iñupiat people also created their own picture writing systems in the early 1900s. This is known as Alaskan Picture Writing.

History

The Iñupiaq people, like other Inuit groups, came from the Thule culture. Around 300 B.C., the Thule people moved from islands in the Bering Sea to what is now Alaska.

Many Iñupiaq groups have names ending in "miut," which means "a people of." For example, the Nunamiut are inland Iñupiaq who traditionally hunted caribou. Between 1890 and 1910, many Nunamiut moved to the coast or other parts of Alaska because of hunger and sickness. Some Nunamiut returned to the mountains in the 1930s.

By 1950, most Nunamiut groups settled in Anaktuvuk Pass. Some Nunamiut remained nomadic, meaning they moved from place to place, until the 1950s.

The famous Iditarod Trail was originally made from old trails used by the Dena'ina and Deg Hit'an Athabaskan Indians and the Iñupiaq Eskimos.

Subsistence and Traditional Life

Iñupiat people are hunter-gatherers, just like most people in the Arctic. They still rely a lot on hunting and fishing for their food. Depending on where they live, they hunt walrus, seal, whale, polar bear, caribou, and various fish. Both inland (Nunamiut) and coastal (Taġiumiut) Iñupiat depend heavily on fish.

Throughout the year, when available, they also eat ducks, geese, rabbits, berries, roots, and shoots.

Inland Iñupiat also hunt caribou, Dall sheep, grizzly bear, and moose. Coastal Iñupiat hunt walrus, seals, beluga whales, and bowhead whales. They also carefully hunt polar bears.

When a whale is caught, it benefits everyone in the Iñupiat community. The animal is cut up, and its meat and blubber are shared according to old traditions. Even family members living far away are entitled to a share of the whale. Muktuk, which is the skin and blubber of bowhead and other whales, is full of vitamins A and C. Eating raw meats and these vitamin-rich foods helps keep people healthy, especially since they have limited access to fruits and vegetables.

A very important value in subsistence hunting is using every part of the animal. For example, hides from seals, moose, caribou, and polar bears are used to make warm clothing. Fur from rabbits, beaver, and other animals is also used to decorate clothes and add warmth. These hides and furs are made into parkas, boots (mukluks), hats, gloves, and slippers. Qiviut, the soft underfur of the Muskox, is gathered and spun into wool for scarves, hats, and gloves. These natural materials keep the Iñupiat warm in the harsh Arctic weather.

Other animal parts are also used. Walrus intestines are made into dance drums and traditional skin boats called qayaq or umiaq. Walrus ivory tusks and bowhead whale baleen are used to create beautiful art. Using these materials shows respect for the animals. There are rules and laws to protect walrus and whales. Hunting walrus just for their ivory is against the law and can lead to serious penalties.

Since the 1970s, oil has become an important source of money for the Iñupiat. The Alaska Pipeline carries oil from Prudhoe Bay to the port of Valdez. However, oil drilling in the Arctic can sometimes conflict with the traditional way of life, especially whaling.

The Iñupiat also eat different kinds of berries. They mix berries with animal fat to make a traditional dessert. They also boil berries with rosehips and highbush cranberries to make syrup.

Culture

Traditionally, some Iñupiat people lived in permanent villages, while others moved around. Some villages in the area have been home to indigenous groups for over 10,000 years.

The Nalukataq is a spring whaling festival among the Iñupiat. This festival celebrates traditional whale hunting. It honors the whale's spirit for giving its body to feed entire villages. Dance groups from across the North perform songs and dances to honor the whale's spirit.

The Iñupiat Ilitqusiat is a list of important values for the Iñupiat people. Elders in Kotzebue, Alaska created this list, and these values are important to other Iñupiat communities too. They include:

- Respect for elders

- Hard work

- Hunter's success

- Family roles

- Humor

- Respect for nature

- Knowledge of family tree

- Respect for others

- Sharing

- Love for children

- Cooperation

- Avoiding conflict

- Responsibility to tribe

- Humility

- Spirituality

These values guide how Iñupiat people live their lives. They are often seen in their traditional hunting and gathering practices.

There is also an Iñupiat culture-focused college called Iḷisaġvik College. It is located in Utqiaġvik.

Current Issues

Iñupiat people are very concerned about climate change. It is threatening their traditional way of life in many ways:

- Thinning sea ice makes it harder to hunt bowhead whales, seals, walrus, and other traditional foods. It also changes where marine mammals travel. Thin ice can also be dangerous, as people might fall through it.

- Warmer winters make travel more risky and unpredictable. More storms form, making journeys difficult.

- Later-forming sea ice leads to more flooding and erosion along the coast. This is because there are more storms in the fall, which directly threatens many coastal villages.

The Inuit Circumpolar Council, a group that represents indigenous peoples of the Arctic, says that climate change is a threat to their human rights.

As of the 2000 U.S. Census, there were over 19,000 Iñupiat people in the United States. Most of them live in Alaska.

Iñupiat Nunaŋat (Iñupiat Territories)

North Slope Borough: Anaktuvuk Pass (Anaqtuuvak, Naqsraq), Atqasuk (Atqasuk), Utqiaġvik (Utqiaġvik, Ukpiaġvik), Kaktovik (Qaaktuġvik), Nuiqsut (Nuiqsat), Point Hope (Tikiġaq), Point Lay (Kali), Wainwright (Ulġuniq)

Northwest Arctic Borough: Ambler (Ivisaappaat), Buckland (Nunatchiaq, Kaŋiq), Deering (Ipnatchiaq), Kiana (Katyaak, Katyaaq), Kivalina (Kivalliñiq), Kobuk (Laugviik), Kotzebue (Qikiqtaġruk), Noatak (Nuataaq ), Noorvik (Nuurvik), Selawik (Siilvik, Akuligaq ), Shungnak (Isiŋnaq, Nuurviuraq)

Nome Census Area: Brevig Mission (Sitaisaq, Sinauraq), Diomede (Iŋalik), Golovin (Siŋik), Koyuk (Kuuyuk), Nome (Siqnazuaq, Sitŋasuaq), Shaktoolik (Saqtuliq), Shishmaref (Qigiqtaq), Teller (Tala, Iġaluŋniaġvik), Wales (Kiŋigin), White Mountain (Natchirsvik), Uŋalaqłiq

Notable Iñupiat

- William L. Iggiagruk Hensley (b. 1941) – a strong supporter of Native Alaskan rights and a U.S. politician.

- Ada Blackjack (1898–1983) – lived alone for two years on an uninhabited island north of Siberia.

- Edna Ahgeak MacLean (b. 1944) – an Iñupiaq language expert, anthropologist, and educator.

- Eileen MacLean (1949–1996) – an Alaska state legislator and educator.

- Andrew Okpeaha MacLean – a writer, director, and filmmaker, known for On the Ice.

- Eddie Ahyakak (b. 1977) – an Iñupiaq marathon runner and expert mountaineer who appeared on Ultimate Survival Alaska.

- Irene Bedard (b. 1967) – an actress.

- Ticasuk Brown (1904–1982) – an educator, poet, and writer.

- Charles "Etok" Edwardsen, Jr. (1943—2015) – an activist for Alaska Native land claims.

- Ronald Senungetuk (1933—2020) – a sculptor, silversmith, and educator.

- Joseph E. Senungetuk (b. 1940) – a writer and artist, author of Give or Take a Century: An Eskimo Chronicle.

- William Oquilluk (1896–1972) – author of People of Kauwerak – Legends of the Northern Eskimo, and a storyteller.

- Allison Akootchook Warden (b. 1971) – an internationally recognized artist.

- Kenneth Utuayuk Toovak (1923—2009) – an ice scientist and Iñupiat spiritualist.

- Sonya Kelliher-Combs (b. 1969) – a mixed media artist with Iñupiaq, Athabascan, German, and Irish heritage.

- Agnes Hailstone – featured in the National Geographic TV series Life Below Zero.

- Sadie Neakok – the first female magistrate (judge) in Alaska.

- Ray Mala (1906–1952) – an actor.

- Joan Kane – a poet.

- dg nanouk okpik – a poet.

- James Dommek Jr. – a writer and musician, author of Midnight Son.

- Alice Qannik Glenn (b. 1989) – a podcaster and producer.

- Howard Rock (1911–1976) – a supporter of Alaska Native land claims, writer, and founder of the Tundra Times newspaper.

- Tara Sweeney – the 13th Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs.

- Ariel Tweto (b. 1987) – a TV personality, producer, and actress, known for her roles on Flying Wild Alaska and Native Shorts.

- John Baker (musher) – a dog musher, pilot, and motivational speaker.

- Shirley Reilly – a Team USA athlete, with 4 medals in the Paralympic Games.

- Eben Hopson – an American politician and founder of the Inuit Circumpolar Council.

- Josiah Patkotak – an American politician, member of the Alaska House of Representatives.