Trans-Alaska Pipeline System facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Trans-Alaska Pipeline System |

|

|---|---|

The trans-Alaska oil pipeline,

as it zig-zags across the landscape |

|

Location of trans-Alaska pipeline

|

|

| Location | |

| Country | Alaska, United States |

| Coordinates | 70°15′26″N 148°37′8″W / 70.25722°N 148.61889°W |

| General direction | North-South |

| From | Prudhoe Bay, Alaska |

| Passes through | Deadhorse Delta Junction Fairbanks Fox Glennallen North Pole |

| To | Valdez, Alaska |

| Runs alongside | Dalton Highway Richardson Highway Elliott Highway |

| General information | |

| Type | Pump stations |

| Owner | Alyeska Pipeline Service Company |

| Partners | BP (1970–2020) ConocoPhillips (1970–present) Exxon Mobil (1970–present) Hilcorp Energy Company (2020–present) Koch Industries (2003–2012) Unocal Corporation (1970–2019) Williams Companies (2000–2003) |

| Commissioned | 1977 |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 800.3 mi (1,288.0 km) |

| Maximum discharge | 2.136 million bbl/d (339,600 m3/d) |

| Diameter | 48 in (1,219 mm) |

| No. of pumping stations | 11 |

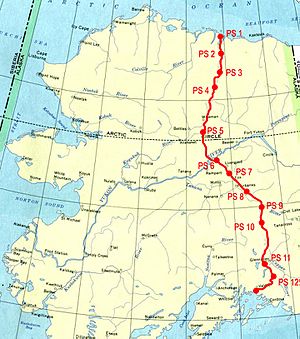

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) is a huge system that moves oil across Alaska. It includes a long pipeline, 11 pump stations, smaller connecting pipelines, and a special port called the Valdez Marine Terminal. TAPS is one of the biggest pipeline systems in the world. People often call it the Alaska pipeline or Alyeska pipeline. These names usually refer to the 800 miles (1,287 km) long pipeline that carries oil from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez. The pipeline is owned by a company called the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company.

The pipeline was built between 1975 and 1977. This happened after the 1973 oil crisis caused oil prices to go up a lot in the United States. Because of the higher prices, it became worth it to get oil from the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field. Before building started, there were many discussions about the environment, laws, and politics. The pipeline was only built after new laws were passed to help solve these issues.

Building the pipeline was very difficult because of the extreme cold and isolated land. Engineers had to find new ways to build on permafrost, which is ground that stays frozen all year. The project brought thousands of workers to Alaska, making towns like Valdez, Fairbanks, and Anchorage grow very quickly.

The first oil flowed through the pipeline in the summer of 1977. Since then, there have been a few oil leaks from things like accidents or damage. By 2014, the pipeline had moved over 17 billion barrels (2.7×109 m3) of oil. The pipeline can carry more than 2 million barrels of oil each day, but it usually carries much less now. If the oil flow becomes too slow, the pipeline could freeze.

Contents

How the Pipeline Started

Discovering Oil in Alaska

For thousands of years, Iñupiat people in northern Alaska used oil-soaked dirt as fuel. Whalers later saw this "pitch" and knew it was petroleum. In the early 1900s, geologists found more oil seeps in northern Alaska. After World War I, the United States Navy needed a steady supply of oil for its ships. So, President Warren G. Harding set aside areas in Alaska, called Naval Petroleum Reserves, for future oil drilling.

Exploration in these reserves began in the 1920s, but it was difficult. During World War II, the search for oil became more urgent. The United States Geological Survey explored the area until 1953. They found some oil fields, but it was too expensive to get the oil out.

Finding Prudhoe Bay Oil

In 1957, a company called Richfield Oil found a lot of oil near the Swanson River in southern Alaska. This was Alaska's first big oil field and led to more discoveries. By 1965, many oil and natural gas fields were found. Experts believed that the area north of the Brooks Range in Alaska also held large amounts of oil. The main challenges were the remote location and harsh weather.

In 1967, Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) started exploring the Prudhoe Bay area. In March 1968, they struck oil! A second well also found oil. Together, these wells confirmed the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field, which became the largest oil field in North America. It held more than 25 billion barrels (4.0×109 m3) of oil.

How to Move the Oil?

The big question was how to get this oil to markets in the U.S. Building a pipeline was one idea, but it would be very long and expensive. Other ideas included giant 12-engine tanker airplanes, tanker submarines that could travel under the Arctic ice, or extending the Alaska Railroad.

To test if oil tankers could sail through the ice, a special ship called the SS Manhattan tried to go through the Northwest Passage in 1969. It made it, but the ship was damaged by ice. It was decided that shipping oil by ice-breaking tankers was too risky. So, a pipeline was the only good way to move the oil to the nearest ice-free port, which was Valdez, almost 800 miles (1,300 km) away.

Building Alyeska and Facing Challenges

Starting the Pipeline Plan

In February 1969, before the SS Manhattan even sailed, three oil companies (ARCO, BP, and Humble Oil) formed a group called the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS). They asked the United States Department of the Interior for permission to study a pipeline route from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez. They quickly ordered huge 48-inch (122 cm) steel pipes from Japan, as no American company made pipes that big.

In June 1969, TAPS officially asked for a permit to build the pipeline across 800 miles (1,300 km) of public land. They also wanted to build a highway next to the pipeline for construction and maintenance.

Problems with Permafrost

An expert named Max Brewer warned that burying most of the pipeline would not work. He explained that the hot oil would melt the permafrost (frozen ground) underneath, causing the pipeline to sink into mud. This report was sent to Congress, who had to approve the project because it needed more land than allowed by old laws.

Also, a land freeze was in place since 1966 to protect land claimed by Alaska Native groups. TAPS tried to get permission from Native villages along the route. By late 1969, most villages agreed to let the pipeline cross their land. However, some Native groups and environmental groups later asked a judge to stop the project.

Legal Delays

On April 1, 1970, a judge ordered the Interior Department not to issue a construction permit. Less than two weeks later, the judge stopped the project completely. Environmental groups argued that the pipeline project broke two important laws: the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 and the National Environmental Policy Act.

After this, the TAPS group was reorganized into a new company called the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company. Its new leader, Edward L. Patton, worked hard to resolve the issues, especially the land claims by Alaska Natives.

Why People Opposed the Pipeline

Opposition to the pipeline came from two main groups: Alaska Native groups and conservationists (people who protect nature). Both groups used legal action to stop the pipeline, delaying construction until 1973.

Environmental Concerns

Environmental groups worried about the pipeline's effect on Alaska's wild lands. They used the new National Environmental Policy Act to argue that the project needed more study. Engineers also had concerns about building on permafrost.

Alyeska had to do more research, and a detailed environmental report was published in 1971. Many people criticized it, saying it didn't fully explain the effects on the Alaska tundra, pollution, or harm to animals. However, the report did say that other ways of moving oil (like a railroad or a different route) would be even worse for the environment.

One big concern was the plan to build a highway next to the pipeline. Environmentalists worried that the road would stay forever, unlike the pipeline which might be removed one day. They pointed out that plants grow very slowly in the Arctic.

The most famous part of the environmental debate was about caribou. People worried the pipeline would block their traditional migration routes, making it harder for them to find food and survive. Anti-pipeline ads even showed pictures of caribou with slogans like, "There is more than one way to get caribou across the Alaska Pipeline." Alyeska later planned for special crossing points to help caribou move across the pipeline.

Native Concerns

Alaska Native groups were upset because the pipeline would cross their traditional lands, but they wouldn't get any direct money from it. They had a history of fighting for their land rights, like the Tlingit natives who won a settlement in 1968. This put pressure on the government to solve the Native land claims quickly.

The Alaska Federation of Natives asked for a large settlement: 40 million acres (160,000 km2) of land and $500 million. The issue was stuck until Alyeska started pushing Congress to pass a Native claims act. In October 1971, President Richard Nixon signed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA). This law gave Native groups $962.5 million and 148.5 million acres (601,000 km2) of federal land. In return, they gave up their land claims, including the path of the pipeline.

Natives also worried that the pipeline would disrupt their traditional way of life. They feared it would scare away whales and caribou, which they relied on for food.

Legal Battles and Political Decisions

Alyeska and the oil companies continued to fight for the pipeline in courts and Congress. They argued that the pipeline's design would protect the environment. For example, they showed that caribou could jump over a similar water pipeline. They also planned for special insulation to prevent permafrost melting and systems to detect oil leaks.

In March 1972, a huge 9-volume environmental report was released. It generally approved the pipeline. After more arguments, a judge lifted the ban on the project in August 1972. However, an appeals court later said that while the environmental study was good, the pipeline still needed a larger right-of-way than allowed by the old Mineral Leasing Act. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case, so Alyeska had to go back to Congress.

Congress Steps In

Alyeska and the oil companies asked Congress to change the Mineral Leasing Act or create a new law. Hearings began in March 1973. Environmental groups tried to convince Congress to build a pipeline through Canada or a railroad instead. However, these alternatives would have caused even more environmental damage.

After many debates, Congress passed an amendment that said the pipeline project met all environmental rules and allowed for the larger right-of-way. Vice President Spiro Agnew cast the tie-breaking vote in the Senate to approve it.

The Oil Crisis and Final Approval

On October 17, 1973, several Arab oil-producing countries stopped selling oil to the United States. This caused the 1973 oil crisis. Gas prices shot up, and there were shortages. Americans demanded a solution, and President Richard Nixon pushed for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline as part of the answer.

Nixon had supported the pipeline even before the crisis. On November 8, 1973, he said it was his top priority. Under pressure from the public, Congress quickly passed the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act. This law removed all legal obstacles, offered financial help, and granted the right-of-way for the pipeline. Nixon signed it into law on November 16, 1973. Construction could finally begin.

Building the Pipeline

Even though the legal issues were settled by January 1974, actual construction on the pipeline didn't start until March. This was because of the cold weather, the need to hire thousands of workers, and the building of the Dalton Highway. Between 1974 and July 28, 1977, when the first oil reached Valdez, tens of thousands of people worked on the pipeline. Many came to Alaska for the high-paying jobs during a time when other parts of the U.S. were in a recession.

Workers faced long hours, freezing temperatures, and tough conditions. Difficult areas like Atigun Pass and Keystone Canyon forced them to find creative solutions. More than $8 billion was spent to build the 800 miles (1,300 km) pipeline, the Valdez Marine Terminal, and 12 pump stations. Sadly, 32 Alyeska and contract employees died during the construction.

What Changed Because of the Pipeline

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System changed Alaska, the United States, and even the world. It had big effects on the economy, the land, and how people lived.

Boomtowns and Big Changes

Building the pipeline caused a huge economic boom in towns along its route. Before construction, most people in Fairbanks, which was still recovering from a flood in 1967, strongly supported the pipeline. But by 1976, after dealing with more crime, crowded public services, and many new people, 56 percent of Fairbanks residents felt the pipeline had made things worse.

The boom was even bigger in Valdez. Its population jumped from 1,350 in 1974 to over 8,000 by 1976. Home prices skyrocketed. A house that cost $40,000 in 1974 sold for $80,000 in 1975. Rent also went way up. Some small cabins with no plumbing rented for $500 a month. In Fairbanks, one two-bedroom house had 45 pipeline workers sharing beds on a rotating schedule!

High salaries for pipeline workers meant they spent a lot of money. This led to other businesses in Alaska having to pay higher wages, which many couldn't afford. Job turnover was very high. For example, a taxi company in Fairbanks had 800% staff turnover. The Fairbanks McDonald's became the second busiest in the world! Stores also faced shortages of everything because Alyeska and its contractors bought so much in bulk.

Alaska's Economy Transformed

Since the pipeline was finished in 1977, the government of Alaska has relied heavily on taxes from oil companies. Before 1976, Alaska had the highest personal income tax rate in the U.S. Thirty years after the pipeline started, Alaska had no personal income tax! The state's economy grew massively.

The pipeline and the oil it carried brought billions of dollars into Alaska. By 1982, just five years after oil started flowing, 86.5 percent of Alaska's money came directly from the oil industry. The state collects royalties from oil produced on state land. It also has a property tax on oil facilities and the pipeline itself. There's also a special tax on oil company profits and on the amount of oil produced.

With so much money coming in, Alaskans debated what to do with it. To make sure the money wasn't spent too quickly, the state created the Alaska Permanent Fund. This is a long-term savings account for the state. At least 25 percent of money from oil and mineral extraction must go into this fund. The first deposit was made in 1977.

In 1980, the state created the Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation to manage the fund's investments. They also started the Permanent Fund Dividend program, which gives annual payments to Alaskans from the interest earned by the fund. This means every eligible Alaskan gets a check each year!

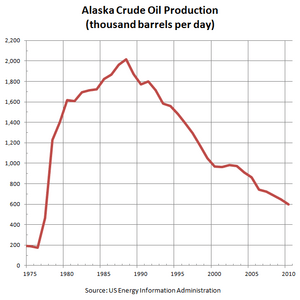

Oil Prices and Social Impact

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline didn't immediately change global oil prices when it started in 1977. It took a few years to reach full production. However, it played a role in the 1979 energy crisis when oil prices went up again. Prices stayed high until the late 1980s. In 1988, the pipeline carried 25 percent of all U.S. oil production. As oil production in Alaska has gone down, the pipeline's share of U.S. oil has also decreased.

The pipeline also attracts thousands of tourists each year. Many famous people have visited, including President Gerald Ford. There have been movies and books about the pipeline, and it has inspired various artworks. Welders who worked on the pipeline often made "pipeline maps" from scrap pipe, shaped like Alaska with the pipeline's path marked.

The pipeline also led to many migrant workers coming to Alaska, which sometimes caused tension with local Inuit people. However, many local Inuit also rely on the pipeline and the oil industry for jobs, income, and even heat and energy.

How the Pipeline Works

Oil enters the Trans-Alaska Pipeline from several oil fields in northern Alaska, like Prudhoe Bay. The oil comes out of the ground hot, around 120 °F (49 °C). By the time it reaches Pump Station 1, it cools to about 111 °F (44 °C). The oil then travels the 800.3 miles (1,288.0 km) length of the pipeline to Valdez. In 1988, it took about 4.5 days for oil to travel the whole pipeline. By 2018, it took 18 days because the flow rate had slowed down.

The pipeline has 11 pump stations along its route. These stations keep the oil moving. Only five stations are usually running now. The pumps are powered by natural gas or liquid fuel.

The pipeline crosses 34 major rivers and almost 500 smaller ones. Its highest point is at Atigun Pass, 4,739 feet (1,444 m) above sea level. The pipeline was built in 40 and 60-foot (12.2 and 18.3-meter) sections, which were then welded together. Over 78,000 special supports hold up the parts of the pipeline that are above ground. The pipeline also has 178 valves to control oil flow.

At the end of the pipeline is the Valdez Marine Terminal. This huge facility can store 9.18 million barrels (1,460,000 m3) of oil in 18 large tanks. It also has berths where oil tankers can dock and be filled. Since 1977, over 19,000 tankers have been filled here.

Keeping the Pipeline Running

The pipeline is checked several times a day, mostly by air, but also by foot and road patrols. They look for leaks or any problems with the pipe. However, most of the maintenance is done by special devices called "pipeline pigs".

The most common type of pig is the scraper pig. It travels through the pipeline and scrapes off wax that builds up on the inside walls. This wax can cause problems if it gets too thick. Other pigs look for corrosion (rust) using magnets or sound waves. Some pigs check for bends or buckles in the pipeline. "Smart" pigs can do many tasks at once. These pigs are usually put into the pipeline at Prudhoe Bay and travel all the way to Valdez.

Another important maintenance task is replacing sacrificial anodes. These are special metal pieces buried along the underground parts of the pipeline. They help prevent the pipeline from corroding due to electrical reactions in the soil.

The Pipeline's Future

As less oil is produced, the flow rate in the pipeline slows down. This means the oil spends more time in the pipeline and gets colder. It's very important that the oil doesn't freeze (below 32°F), because water in the oil could separate and freeze, causing the pipeline to crack. A study in 2011 said that the minimum flow to avoid freezing in winter was 300,000 to 350,000 barrels per day.

However, another study by BP suggested that with special heaters installed along the pipeline, the minimum flow could be as low as 70,000 barrels per day (11,000 m3/d). This would allow the pipeline to operate much longer. Experts believe the pipeline can continue to work until at least 2032, and with improvements, possibly even until 2075.

Over the years, the ownership of the pipeline has changed. Big oil companies have bought and sold their shares. For example, in 2020, BP sold its large share to Hilcorp Energy Company.

By law, Alaska must remove all traces of the pipeline once oil extraction is finished. No date has been set for this, but plans are always being updated.

See also

In Spanish: Sistema de oleoducto Trans-Alaska para niños

In Spanish: Sistema de oleoducto Trans-Alaska para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |