Spiro Agnew facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Spiro Agnew

|

|

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1972

|

|

| 39th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1969 – October 10, 1973 |

|

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Hubert Humphrey |

| Succeeded by | Gerald Ford |

| 55th Governor of Maryland | |

| In office January 25, 1967 – January 7, 1969 |

|

| Preceded by | J. Millard Tawes |

| Succeeded by | Marvin Mandel |

| 3rd Executive of Baltimore County | |

| In office December 6, 1962 – December 8, 1966 |

|

| Preceded by | Christian H. Kahl |

| Succeeded by | Dale Anderson |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Spiro Theodore Agnew

November 9, 1918 Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died | September 17, 1996 (aged 77) Berlin, Maryland, U.S. |

| Resting place | Dulaney Valley Memorial Gardens |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | University of Baltimore (LLB) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1941–1945 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Commands | Service Company, 54th Armored Infantry Battalion |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Bronze Star |

Spiro Theodore Agnew (born November 9, 1918 – died September 17, 1996) was an American politician. He served as the 39th Vice President of the United States from 1969 until he resigned in 1973. He was the second Vice President in U.S. history to resign from this important role.

Agnew was born in Baltimore, Maryland. His father was a Greek immigrant, and his mother was American. He studied at Johns Hopkins University and later earned a law degree from the University of Baltimore School of Law. Before becoming Vice President, he held several public offices. He was the Baltimore County Executive from 1962 to 1966. Then, he became the Governor of Maryland, serving from 1967 to 1969.

In 1968, Richard Nixon chose Agnew as his running mate for the presidential election. Agnew was known for his strong stance on "law and order," which appealed to many voters. Nixon and Agnew won the election, defeating Hubert Humphrey and Edmund Muskie. As Vice President, Agnew often spoke out against those who criticized the government. In 1972, Nixon and Agnew were re-elected in a landslide victory.

However, in 1973, Agnew faced serious accusations related to his time as a public official in Maryland. He was accused of taking payments from contractors. These payments continued even when he was Vice President. After months of denying the accusations, Agnew pleaded "no contest" to a charge of tax evasion and resigned from office. President Nixon then chose Gerald Ford to replace him. After leaving office, Agnew lived a quiet life, rarely appearing in public. He wrote a novel and a memoir, both defending his actions. He passed away in 1996 at the age of 77 from an undiagnosed illness.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Family Background

Spiro Agnew's father, Theophrastos Anagnostopoulos, was born in Greece around 1877. He moved to the United States in 1897 and changed his name to Theodore Agnew. He opened a diner in New York and later a restaurant in Baltimore. Theodore was a very intelligent man who loved to read and learn about philosophy.

In Baltimore, Theodore met Margaret Pollard, who was born Margaret Marian Akers in Virginia in 1883. She worked in government offices before marrying William Pollard. After William died, Theodore and Margaret married in 1917. Spiro Agnew was born almost a year later, on November 9, 1918. The family lived in a small apartment in downtown Baltimore.

Childhood and Education

Spiro was baptized as an Episcopalian, following his mother's wishes, even though his father was Greek Orthodox. His father, Theodore, had a strong influence on Spiro. Spiro later said he was proud to have grown up "in the light of my father."

In the 1920s, the Agnew family did well. Theodore bought a bigger restaurant, and they moved to a house in the Forest Park area of Baltimore. Spiro attended Garrison Junior High and Forest Park High School. However, their good fortune ended with the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The restaurant closed, and their savings were lost when a bank failed. The family had to sell their house and move to a smaller apartment. Spiro helped out by working part-time jobs. As he grew up, he preferred to be called "Ted" and became less connected to his Greek heritage.

In 1937, Agnew started at Johns Hopkins University, studying chemistry. He found the studies difficult and was worried about his family's money problems. In 1939, he decided to study law instead. He left Johns Hopkins and began night classes at the University of Baltimore School of Law. To support himself, he worked as an insurance clerk.

Marriage and Family Life

While working at the Maryland Casualty Company, Spiro met Elinor Judefind, who was known as "Judy." They were married in Baltimore on May 27, 1942. They had four children: Pamela Lee, James Rand, Susan Scott, and Elinor Kimberly.

Military Service and Postwar Life

World War II Service

Soon after his marriage, Agnew was drafted into the United States Army during World War II. He completed basic training and then attended Officer Candidate School. He became a second lieutenant in May 1942, just before his wedding.

Agnew served in the U.S. for almost two years before being sent to England in 1944. Later that year, he went to France and joined the 54th Armored Infantry Battalion. He commanded the battalion's service company. His unit fought in important battles, including the Battle of the Bulge. They then moved into Germany as the war ended. Agnew returned home in November 1945. He received the Bronze Star Medal for his service.

Returning to Civilian Life

After the war, Agnew continued his law studies and worked as a law clerk. He had mostly been a Democrat, like his father. However, a senior partner at his law firm suggested he become a Republican. There were many young Democrats in Baltimore, but fewer Republicans. Agnew took the advice and registered as a Republican in 1947 when he moved to Lutherville, Maryland.

In 1947, Agnew earned his law degree and passed the bar exam in Maryland. He started his own law practice but it was not very successful. He took jobs as an insurance investigator and later as a store detective for a supermarket chain. In 1951, he was briefly called back to the Army during the Korean War. In 1952, he returned to his law practice, focusing on labor law.

In 1955, Agnew moved his law office to Towson, the county seat of Baltimore. He also moved his family to Loch Raven, Baltimore. He became active in his community, serving as president of the local Parent-Teacher Association and joining the Kiwanis club. He enjoyed a typical suburban life.

Beginning in Public Service

First Steps in Politics

Agnew first tried to enter politics in 1956. He wanted to be a Republican candidate for the Baltimore County Council but was not chosen by party leaders. However, he worked hard for the Republican Party in the election. When Republicans won a majority on the council, Agnew was appointed to the county Zoning Board of Appeals for one year. This job helped his law practice and gave him more recognition. In 1958, he was reappointed for a three-year term and became the chairman.

In 1960, Agnew ran for a seat on the county circuit court but lost. Even though he lost, this attempt made him more well-known. In 1962, the Democrats gained control of the county council and removed Agnew from the Zoning Appeals Board. This action made Agnew seem like an honest public servant who was unfairly treated. He decided to run for Baltimore County Executive, the county's chief leader. Democrats had held this position since 1895.

Agnew's chances in 1962 were helped by a disagreement among the Democrats. Agnew campaigned as a "White Knight" promising change. He supported a bill to end discrimination in public places like parks and restaurants. This was a bold stance at the time. In the November election, Agnew won, even though Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson campaigned for his opponent. Agnew became the highest-ranking Republican in Maryland.

Serving as County Executive

During his four years as county executive, Agnew led a moderately progressive government. He oversaw the building of new schools, increased teachers' salaries, and improved police and water systems. His anti-discrimination bill passed, which gave him a reputation as a liberal. However, its impact was limited because the county was mostly white.

Agnew's relationship with the growing civil rights movement was sometimes difficult. He often prioritized "law and order" and disliked public demonstrations. For example, after a church bombing in Alabama that killed four children, Agnew refused to attend a memorial service. He also spoke out against a planned demonstration supporting the victims.

Some people criticized Agnew for being too close to wealthy business people. He was accused of favoring friends by giving them county insurance contracts without the usual bidding process. Agnew always denied any wrongdoing, saying his opponents were making "outrageous distortions."

In the 1964 United States presidential election, Agnew did not support the conservative Republican candidate, Barry Goldwater. He preferred more moderate candidates. He eventually supported Goldwater, but he believed that choosing such an extreme candidate would cost the Republicans the election.

Governor of Maryland (1967–1969)

Winning the Governorship in 1966

As his term as county executive ended, Agnew knew it would be hard to be re-elected. Instead, he decided to run for governor in 1966. With the support of party leaders, he easily won the Republican primary election.

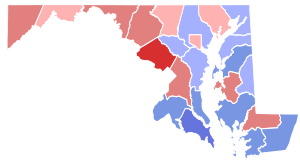

In the Democratic Party, the nomination for governor was won by George P. Mahoney, who supported segregation. This caused a split among Democrats, leading to a third candidate, Hyman A. Pressman. In wealthy Montgomery County, Maryland, a group called "Democrats for Agnew" formed, and many liberals supported Agnew. Mahoney used the slogan "Your Home is Your Castle. Protect it!" to appeal to racial tensions. Agnew criticized Mahoney, saying voters had to choose between "righteousness and the fiery cross." In the November election, Agnew won, partly because he received 70 percent of the black vote.

After the campaign, it was revealed that Agnew had not reported three alleged attempts to bribe him. These attempts were related to keeping slot machines legal in Southern Maryland. Agnew said he did not report them because no actual money was offered. He was also criticized for owning land near a planned bridge, which some saw as a conflict of interest. Agnew denied any wrongdoing and eventually sold his share of the land.

Agnew as Governor

As governor, Agnew worked on several important issues. He supported tax reform, clean water rules, and ending laws against interracial marriage. He expanded community health programs and created more opportunities for education and jobs for people with low incomes. He also took steps to end segregation in schools. Agnew's fair housing laws were the first of their kind passed in the Southern United States. However, his attempt to adopt a new state constitution was rejected by voters.

Agnew often kept a distance from the state legislature, preferring to spend time with businessmen. Some of these businessmen had been his associates when he was county executive. Officials in the state capital, Annapolis, noticed his close ties to the business community. Some suspected that he "allowed himself to be used by the people around him."

Agnew publicly supported civil rights but did not like the strong tactics used by some black leaders. In mid-1967, racial tensions were high across the country. Riots broke out in Cambridge, Maryland, after a speech by radical student leader H. Rap Brown. Agnew's main concern was maintaining law and order. He called Brown a "professional agitator" and said, "I hope they put him away and throw away the key."

When a government commission said that white racism was the main cause of unrest, Agnew disagreed. He blamed "permissive climate and misguided compassion." He said that lawbreaking had become "socially acceptable." In March 1968, when students at Bowie State College protested, Agnew blamed "outside agitators" and refused to talk with the students. He closed the college and ordered over 200 arrests.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, there were widespread riots across the U.S., including in Baltimore. Agnew declared a state of emergency and called out the National Guard. After order was restored, Agnew called a meeting with over 100 moderate black leaders. Instead of a discussion, he criticized them for not controlling more radical elements. Many white suburbanites supported Agnew's speech. However, members of the black community felt betrayed. One state senator said, "He has sold us out ... he thinks like George Wallace, he talks like George Wallace."

Becoming Vice President (1968)

Choosing a Running Mate

Before the April 1968 riots, Agnew was seen as a liberal Republican. He supported Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York for president in 1968. Agnew was even chairman of Rockefeller's campaign committee. However, Rockefeller surprised everyone by withdrawing from the race in March 1968, without telling Agnew beforehand. Agnew felt disappointed and insulted.

Soon after, supporters of former Vice President Richard Nixon approached Agnew. Agnew had no strong feelings against Nixon and considered him his "second choice." When Agnew and Nixon met, they got along well. Nixon was impressed by Agnew's strong stance after the Baltimore riots. When Rockefeller re-entered the race in April, Agnew was not as enthusiastic about supporting him.

In May, Nixon mentioned Agnew as a possible running mate. Agnew continued to meet with Nixon and his team. It seemed he was moving closer to Nixon's campaign. At the same time, Agnew publicly said he only wanted to finish his term as governor.

The Republican Convention

As Nixon prepared for the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach in August 1968, he thought about who to choose as his running mate. He wanted someone who would unite the party, not divide it. Agnew was planning to go to the convention as a "favorite son" candidate, meaning he was not committed to any main candidate.

At the convention, Agnew changed his plans and nominated Nixon for president. Nixon won the nomination on the first vote. During discussions about a running mate, Nixon kept his decision private. He wanted a moderate candidate. On August 8, after meeting with his advisors, Nixon announced that Agnew was his choice. Delegates formally nominated Agnew for Vice President later that day.

Many people did not know who Agnew was. A common reaction to the news was "Spiro who?" People interviewed on television even joked that "Spiro" sounded like a disease or a type of egg.

The Campaign Trail

In the 1968 election, the Nixon-Agnew team faced two main opponents. The Democrats nominated Vice President Hubert Humphrey and Senator Edmund Muskie. The former governor of Alabama, George Wallace, ran as a third-party candidate. Nixon wanted Agnew to have a lot of freedom in the campaign. He also wanted Agnew to play an "attack dog" role, criticizing opponents, just as Nixon had done for President Eisenhower.

At first, Agnew tried to be a moderate, highlighting his civil rights record in Maryland. But as the campaign went on, he became more aggressive. He used strong "law and order" language, which pleased many voters in the South but worried some liberals in the North.

Agnew often made headlines for his controversial comments. He used offensive terms to describe different groups of people. He also seemed to dismiss poverty by saying, "if you've seen one slum you've seen them all." He criticized Humphrey, comparing him to a weak leader. Democrats made fun of Agnew in their commercials. While Agnew's comments angered many, Nixon did not stop him. This strong talk appealed to many voters, especially in the Southern states, and helped counter Wallace's appeal. Agnew's words also helped unite "white backlash" voters around ideas like order, personal responsibility, and law and order.

In late October, The New York Times published an article questioning Agnew's financial dealings in Maryland. Nixon defended Agnew, calling the article "gutter politics." On November 5, the Republicans won the election. Nixon and Agnew had a narrow lead in the popular vote. However, they won more electoral votes, with Nixon getting 301, Humphrey 191, and Wallace 46. Agnew was credited with helping the party win several key states in the South and boosting Nixon's support in suburbs across the country.

Vice Presidency (1969–1973)

Starting the Role

After the 1968 election, Agnew was unsure what his role as Vice President would be. Nixon, who had been Vice President for eight years, wanted to give Agnew more responsibilities than he had. Nixon initially gave Agnew an office in the West Wing of the White House, which was new for a Vice President. However, Agnew later moved to another building. Nixon told the press that Agnew would have "new duties" and would use his experience as a county executive and governor to help with federal-state relations and urban issues.

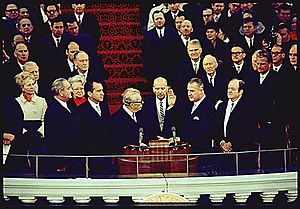

During the transition, Agnew traveled a lot and enjoyed his new status. He hired staff who had worked with him in Maryland. Agnew was sworn in with Nixon on January 20, 1969. He did not give a speech, as was the custom.

Soon after, Nixon appointed Agnew to lead the Office of Intergovernmental Relations and other government commissions. However, Agnew was not part of Nixon's closest group of advisors. Nixon preferred to work with a small, trusted team. Agnew's pride was hurt by the negative news coverage he received during the campaign. He tried to improve his reputation by working hard. He spent more time presiding over the Senate in his first year than any Vice President in a long time. He also met with senators to build good relationships. Although he couldn't speak on foreign policy, he attended White House staff meetings and spoke about urban issues.

Attacking Opponents

Agnew's public image as a strong critic of violent protests continued into his vice presidency. At first, he tried to be more moderate, like Nixon. But he still called for a firm approach against violence. In a speech in Honolulu in May 1969, he warned about "counterdemonstrators" who took the law into their own hands.

In October 1969, Nixon asked Agnew to speak out against anti-war protests. Agnew handled this well, and Nixon then tasked him with attacking Democrats in general, while Nixon himself stayed above the arguments. This was similar to the role Nixon had played as Vice President. Agnew enjoyed this new role.

Agnew gave a series of speeches criticizing political opponents. In New Orleans, he blamed liberal elites for allowing violence. In Mississippi, he said the South had been unfairly criticized by "liberal intellectuals." He argued that the administration and Southern whites had much in common. These remarks were designed to attract Southern white voters to the Republican Party.

After these speeches, Nixon gave his "Silent Majority" speech, asking Americans to support his Vietnam policy. The press criticized Nixon's speech. Nixon's speechwriter wrote a response for Agnew to deliver in Des Moines, Iowa. The White House made sure the speech was broadcast nationwide.

In his Des Moines speech, Agnew attacked the media. He complained that after Nixon's speech, the news was "subjected to instant analysis and querulous criticism" by a "small band of network commentators." He questioned if a form of censorship existed when news was decided by a "handful of men" who had their own biases.

This speech put into words what many Republicans and conservatives felt about the news media. Television executives and commentators were outraged. However, conservatives praised the speech, and it made Agnew popular among the right wing. Agnew considered this one of his best moments.

In November, Agnew continued his attacks, criticizing The New York Times and The Washington Post. He accused them of having a narrow viewpoint different from most Americans. He said the time when news commentators had "diplomatic immunity" from criticism was over. After this, Nixon sought to improve relations with the media, and Agnew's attacks stopped. Agnew's approval ratings went up, and he gained a strong base among conservatives, boosting his chances for the 1976 presidential election.

1970: Protests and Elections

Agnew's strong speeches made him a popular speaker at Republican fundraising events. He traveled widely in early 1970, raising money for the party. He attacked "supercilious sophisticates" and promised to keep speaking for the "Silent Majority."

Agnew tried to increase his influence with Nixon, despite opposition from Nixon's chief of staff. Agnew successfully argued for attacking Viet Cong bases in Cambodia, a decision Nixon supported.

Student protests against the Vietnam War continued. Agnew criticized those who failed to guide students. After the Kent State shootings, Agnew did not soften his attacks on demonstrators. He said he was responding to a "general malaise that argues for violent confrontation instead of debate." Nixon asked Agnew to avoid remarks about students, but Agnew disagreed and said he would only stop if Nixon directly ordered it.

Nixon wanted Republicans to win control of the Senate in the 1970 midterm elections. He initially planned to limit Agnew's role to fundraising, but he later decided to let Agnew campaign as the spokesman for the Silent Majority.

In September, Agnew began his campaign, known for its harsh words and memorable phrases. He attacked "pusillanimous pussyfooting" liberals and spoke for the "Forgotten Man of American politics." He warned voters to remove candidates who held radical views. Nixon encouraged Agnew to continue this strategy.

Nixon wanted to defeat Senator Charles Goodell, a Republican who opposed the Vietnam War. Nixon did not want to be seen as directly working against a fellow Republican. Agnew campaigned in New York, making it clear he supported the Conservative Party candidate, James L. Buckley. Both Nixon and Agnew campaigned heavily in the final days before the election. The results were disappointing for Republicans, who gained only two Senate seats and lost eleven governorships. However, Agnew was pleased when Buckley defeated Goodell in New York.

Re-election in 1972

In 1971, it was unclear if Agnew would be Nixon's running mate for the 1972 election. Nixon and his aides were not always happy with Agnew's independent and outspoken nature. Nixon considered replacing him with Treasury Secretary John Connally. Agnew also disagreed with some of Nixon's policies, especially his approach to China. It was not until July 1972 that Nixon asked Agnew to be his running mate again, and Agnew accepted.

Nixon told Agnew to avoid personal attacks on the press and the Democratic presidential candidate, Senator George McGovern. He wanted Agnew to focus on the positive achievements of the Nixon administration. At the 1972 Republican National Convention, Agnew was welcomed as a hero. He delivered a speech highlighting the administration's successes and avoided his usual harsh language. However, he did criticize McGovern for supporting busing and suggested McGovern would beg North Vietnam for the return of American prisoners of war.

The Watergate scandal was a minor issue during the campaign. Agnew was not involved and knew nothing about it until he read about it in the news. He thought the break-in was foolish. Nixon instructed Agnew not to attack McGovern's running mates.

Nixon took a more dignified approach in the campaign, but he still wanted McGovern's positions criticized. This task fell partly to Agnew. Agnew told the press he wanted to change his image as a partisan campaigner. He defended Nixon on Watergate. When McGovern called the Nixon administration corrupt, Agnew responded by calling McGovern a "desperate candidate."

The election was not close. The Nixon/Agnew ticket won 49 states and over 60 percent of the vote, securing re-election. Agnew campaigned widely for Republican candidates, hoping to position himself for the 1976 election. Despite his efforts, Democrats kept control of both houses of Congress.

After the Vice Presidency (1973–1996)

Life After Resignation

After his resignation in 1973, Agnew moved to his summer home in Ocean City, Maryland. He borrowed money from his friend Frank Sinatra to pay his bills. He hoped to resume his career as a lawyer, but in 1974, the Maryland Court of Appeals removed his license to practice law.

To earn a living, he started a business consulting firm called Pathlite Inc. This company worked with clients around the world. He also pursued other business ventures, including land deals and a partnership in a beer distribution company, but these were not successful. In 1976, he published a novel called The Canfield Decision, which was about a vice president's difficult relationship with his president. The book sold well.

In 1977, Agnew moved to Rancho Mirage, California, and was able to repay the loan from Sinatra. That year, in televised interviews, Nixon claimed he had no direct role in Agnew's resignation. Nixon suggested that Agnew had been unfairly targeted by the liberal media.

In 1980, Agnew published a memoir called Go Quietly ... or Else. In the book, he stated he was completely innocent of the charges that led to his resignation.

After publishing his memoir, Agnew largely stayed out of public view. In a rare TV interview in 1980, he advised young people not to go into politics because too much was expected of those in high office. In 1981, a judge ordered Agnew to repay the state of Maryland money he had taken. After two appeals, Agnew finally paid the sum in 1983.

Final Years and Legacy

For the rest of his life, Agnew kept his distance from the news media and Washington politics. He refused to take calls from President Nixon, still feeling hurt by how he was treated. When Nixon died in 1994, his daughters invited Agnew to the funeral. At first, Agnew refused, but he was persuaded to attend. He received a warm welcome from his former colleagues. He said, "I decided after twenty years of resentment to put it aside."

A year later, Agnew attended a ceremony at the Capitol for the dedication of a bust of him, placed with those of other vice presidents. Agnew commented that the ceremony was more about the office he held than about him personally.

On September 16, 1996, Agnew collapsed at his summer home in Ocean City, Maryland. He was taken to the hospital and died the next evening. The cause of death was undiagnosed acute leukemia. Agnew had been active and healthy into his seventies, playing golf and tennis regularly. His funeral was private, mainly for family. An honor guard from the military fired a 21-gun salute at his graveside. His wife, Judy, passed away in 2012.

At the time of his death, Agnew's legacy was mostly seen in a negative light. The way he left public office, especially after promoting "law and order," made many people feel cynical about politicians. His downfall led to more careful choices for future vice presidents. Many running mates chosen after 1972 were experienced politicians.

Some historians now see Agnew as important in the development of the "New Right" political movement. They argue that he helped popularize the idea that much of the national media was controlled by liberal elites. Agnew's fall from grace shocked conservatives, but it did not stop the growth of the New Right. Agnew, who was the first suburban politician to reach such a high office, helped reshape the Republican Party as the party of "Middle Americans." Even in disgrace, he strengthened the public's distrust of government.

For Agnew himself, despite his rise from Baltimore to almost the presidency, history's judgment was clear. He was the first Vice President of the United States to resign in disgrace. Everything he achieved in public life was overshadowed by that sad event.

See also

In Spanish: Spiro Agnew para niños

In Spanish: Spiro Agnew para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |