Iñupiaq language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Iñupiaq |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uqautchiq Iñupiatun, Uqałiq Iñupiatun, Qaġnuziq Inupiaqtun | ||||

| Native to | United States, formerly Russia; Northwest Territories of Canada | |||

| Region | Alaska; formerly Big Diomede Island | |||

| Ethnicity | 20,709 Iñupiat (2015) | |||

| Native speakers | 2,144, 7% of ethnic population (2007) | |||

| Language family | ||||

| Writing system | Latin (Iñupiaq alphabet) Iñupiaq Braille |

|||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | Alaska, Northwest Territories (as Inuvialuktun, Uummarmiutun dialect) | |||

|

||||

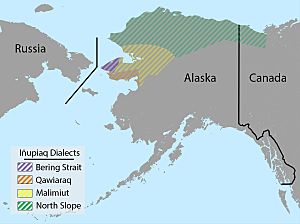

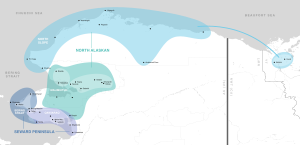

Inupiaq dialects and speech communities

|

||||

|

||||

Iñupiaq or Inupiaq is an Inuit language spoken by the Iñupiat people. You can find Iñupiaq speakers in northern and northwestern Alaska. A small number of speakers also live in the Northwest Territories of Canada.

Iñupiaq is part of the Inuit-Yupik-Unangan language family. It is related to other Inuit languages in Canada and Greenland. However, speakers of Iñupiaq cannot easily understand those other languages.

Today, about 2,000 people speak Iñupiaq. Most speakers are 40 years old or older. This means it is a threatened language. Iñupiaq is one of the official languages of Alaska.

The main types of Iñupiaq are the North Slope Iñupiaq and Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq dialects.

The number of Iñupiaq speakers has gone down since the late 1800s. This happened after English speakers arrived. Also, boarding schools played a role. In these schools, Native Alaskan children were often punished for speaking their own languages.

Despite these challenges, people are working to bring the language back. Many communities are trying to teach Iñupiaq to younger generations.

Contents

The History of Iñupiaq Language

The Iñupiaq language is an Inuit language. Its roots might go back 5,000 years in northern Alaska. About 800 to 1,000 years ago, Inuit people moved east. They traveled from Alaska to Canada and Greenland. Eventually, they lived along the entire Arctic coast.

Iñupiaq dialects are the oldest forms of the Inuit language. They have changed less than other Inuit languages over time.

In the mid to late 1800s, people from Russia, Britain, and America met the Iñupiat. In 1885, the American government put Rev. Sheldon Jackson in charge of education. He made sure that Iñupiat people and all Alaska Natives learned only in English. Speaking Iñupiaq or other native languages was forbidden. Children were often punished for speaking their language. Because of this, many Iñupiat parents stopped teaching Iñupiaq to their children after the 1970s. They feared their children would be punished.

In 1972, the Alaska Legislature passed a new law. It said that if a school had at least 15 students whose main language was not English, the school needed a teacher who spoke that native language fluently.

Today, the University of Alaska Fairbanks offers degrees in Iñupiaq language and culture. There is also a special school called Nikaitchuat Ilisaġviat in Kotzebue. It teaches PreK to 1st grade entirely in Iñupiaq.

In 2014, Iñupiaq became an official language of Alaska. It joined English and nineteen other native languages.

In 2018, Facebook added Iñupiaq as a language option. In 2022, an Iñupiaq version of Wordle was created.

Iñupiaq Dialects

The Iñupiaq language has four main dialects. These are grouped into two larger collections:

- Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq: Spoken on the Seward Peninsula. It is different from other Inuit languages.

- Qawiaraq

- Bering Strait

- Northern Alaskan Iñupiaq: Spoken from the Northwest Arctic and North Slope areas of Alaska. It also extends to the Mackenzie Delta in Canada.

- Malimiut

- North Slope Iñupiaq

| Dialect collection | Dialect | Subdialect | Tribal nation(s) | Populated areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq | Bering Strait | Diomede | Iŋalit | Little Diomede Island, Big Diomede Island (until the late 1940s) |

| Wales | Kiŋikmiut, Tapqaġmiut | Wales, Shishmaref, Brevig Mission | ||

| King Island | Ugiuvaŋmiut | King Island (until the early 1960s), Nome | ||

| Qawiaraq | Teller | Siñiġaġmiut, Qawiaraġmiut | Teller, Shaktoolik | |

| Fish River | Iġałuiŋmiut | White Mountain, Golovin | ||

| Northern Alaskan Iñupiaq | Malimiutun | Kobuk | Kuuŋmiut, Kiitaaŋmiut [Kiitaaġmiut], Siilim Kaŋianiġmiut, Nuurviŋmiut, Kuuvaum Kaŋiaġmiut, Akuniġmiut, Nuataaġmiut, Napaaqtuġmiut, Kivalliñiġmiut | Kobuk River Valley, Selawik |

| Coastal | Pittaġmiut, Kaŋiġmiut, Qikiqtaġruŋmiut | Kotzebue, Noatak | ||

| North Slope / Siḷaliñiġmiutun | Common North Slope | Utuqqaġmiut, Siliñaġmiut [Kukparuŋmiut and Kuuŋmiut], Kakligmiut [Sitarumiut, Utqiaġvigmiut and Nuvugmiut], Kuulugruaġmiut, Ikpikpagmiut, Kuukpigmiut [Kañianermiut, Killinermiut and Kagmalirmiut] | ||

| Point Hope | Tikiġaġmiut | Point Hope | ||

| Point Barrow | Nuvuŋmiut | |||

| Anaktuvuk Pass | Nunamiut | Anaktuvuk Pass | ||

| Uummarmiutun (Uummaġmiutun) | Uummarmiut (Uummaġmiut) | Aklavik (Canada), Inuvik (Canada) |

Extra Geographical Information

Some Iñupiaq dialects are spoken in specific places.

The Bering Strait dialect was spoken on Big Diomede Island. After World War II, the people moved to Siberia. They then spoke a different language. The people of King Island moved to Nome in the 1960s. This dialect might also be heard in Teller.

The Qawiaraq dialect is spoken in Nome. You might also hear it in Koyuk, Mary's Igloo, Council, and Elim. The Teller sub-dialect may be spoken in Unalakleet.

The Malimiutun dialect has two sub-dialects. Both can be found in Buckland, Koyuk, Shaktoolik, and Unalakleet. Other places like Deering and Kiana might also speak it.

The North Slope dialect is a mix of older ways of speaking. In 2010, the Point Barrow dialect was spoken by only a few elders. This dialect is also spoken in places like Kivalina and Utqiaġvik.

How Iñupiaq Sounds

Iñupiaq words are built with sounds. All Iñupiaq dialects use three main vowel sounds: /a/, /i/, and /u/. These vowels can be short or long. Long vowels are written with double letters, like aa, ii, uu.

The Bering Strait dialect has a fourth vowel sound, /e/. This sound is not found in other dialects.

Words usually start with a stop sound (like 'p' or 't') or a fricative sound (like 's'). They can also start with a nasal sound (like 'm' or 'n') or a vowel. In the Uummarmiutun dialect, words can also start with 'h'. For example, "ear" is siun in North Slope, but hiun in Uummarmiutun.

Words can end with a nasal sound, a stop sound, or a vowel.

Writing Iñupiaq

Iñupiaq was first written down by explorers. They tried to write the sounds using letters from their own languages. This often led to different spellings for the same word.

The Iñupiat people later started using the Latin script. This writing system was developed by missionaries in Greenland and Labrador. Native Alaskans also created a system of pictures for writing. However, this system disappeared with its creators.

In 1946, an Iñupiaq minister named Roy Ahmaogak worked with Eugene Nida. They created the Iñupiaq alphabet we use today. It is based on the Latin script. Some small changes have been made since then, but the main system is still the same.

Iñupiaq Alphabet (North Slope and Northwest Arctic)

| A a | Ch ch | G g | Ġ ġ | H h | I i | K k | L l | Ḷ ḷ | Ł ł | Ł̣ ł̣ | M m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | cha | ga | ġa | ha | i | ka | la | ḷa | ła | ł̣a | ma |

| /a/ | /tʃ/ | /ɣ/ | /ʁ/ | /h/ | /i/ | /k/ | /l/ | /ʎ/ | /ɬ/ | /[[Error using : IPA symbol "ʎ̥" not found in list|ʎ̥]]/ | /m/ |

| N n | Ñ ñ | Ŋ ŋ | P p | Q q | R r | S s | Sr sr | T t | U u | V v | Y y |

| na | ña | ŋa | pa | qa | ra | sa | sra | ta | u | va | ya |

| /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | /p/ | /q/ | /ɹ/ | /s/ | /ʂ/ | /t/ | /u/ | /v/ | /j/ |

The Kobuk dialect has an extra letter: ʼ /ʔ/.

Iñupiaq Alphabet (Seward Peninsula)

| A a | B b | G g | Ġ ġ | H h | I i | K k | L l | Ł ł | M m | N n | Ŋ ŋ | P p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | ba | ga | ġa | ha | i | ka | la | ła | ma | na | ŋa | pa |

| /a/ | /b/ | /ɣ/ | /ʁ/ | /h/ | /i/ | /k/ | /l/ | /ɬ/ | /m/ | /n/ | /ŋ/ | /p/ |

| Q q | R r | S s | Sr sr | T t | U u | V v | W w | Y y | Z z | Zr zr | ʼ | |

| qa | ra | sa | sra | ta | u | va | wa | ya | za | zra | ||

| /q/ | /ɹ/ | /s/ | /ʂ/ | /t/ | /u/ | /v/ | /w/ | /j/ | /z/ | /ʐ/ | /ʔ/ |

Extra letters for specific dialects:

- Diomede: e /ə/

- Qawiaraq: ch /tʃ/

Canadian Iñupiaq Alphabet (Uummarmiutun)

| A a | Ch ch | F f | G g | H h | Dj dj | I i | K k | L l | Ł ł | M m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | cha | fa | ga | ha | dja | i | ka | la | ła | ma |

| /a/ | /tʃ/ | /f/ | /ɣ/ | /h/ | /dʒ/ | /i/ | /k/ | /l/ | /ɬ/ | /m/ |

| N n | Ñ ñ | Ng ng | P p | Q q | R r | R̂ r̂ | T t | U u | V v | Y y |

| na | ña | ŋa | pa | qa | ra | r̂a | ta | u | va | ya |

| /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | /p/ | /q/ | /ʁ/ | /ʐ/ | /t/ | /u/ | /v/ | /j/ |

How Iñupiaq Words are Built

Iñupiaq is a polysynthetic language. This means words can be very long. They are built by adding many small parts to a main word. These parts can change the meaning of the word. They can also show if something is happening now, in the past, or in the future. They can also show who is doing the action.

The main part of a word is called a "stem." It gives the basic meaning. Then, other parts are added to it. These parts are like adverbs or adjectives in English. They also show things like tense (when something happens) or mood (how the action is seen).

Iñupiaq nouns have different forms for singular (one), dual (two), and plural (more than two). The language also uses a system called Ergative-Absolutive. This means that the way a noun is marked changes depending on if it's the subject of an action or the object. Iñupiaq does not use "a" or "the" like English. It also does not have gender for nouns.

Iñupiaq Numbers

Iñupiaq uses a base-20 number system. This means it counts in groups of 20. It also has a smaller group of 5.

Here are the numbers from 1 to 20:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| atausiq | malġuk | piŋasut | sisamat | tallimat |

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| itchaksrat | tallimat malġuk | tallimat piŋasut | quliŋŋuġutaiḷaq | qulit |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| qulit atausiq | qulit malġuk | qulit piŋasut | akimiaġutaiḷaq | akimiaq |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| akimiaq atausiq | akimiaq malġuk | akimiaq piŋasut | iñuiññaġutaiḷaq | iñuiññaq |

You can see how the numbers 5 (tallimat) and 15 (akimiaq) are important. Numbers like 7, 8, 16, 17, and 18 are made by adding 1, 2, or 3 to these base numbers. For example, tallimat malġuk means "five and two" (7).

Numbers before a multiple of five often use -utaiḷaq. This means "minus one" or "lacking one." For example, quliŋŋuġutaiḷaq (9) means "lacking one from ten."

Larger numbers are built using groups of 20. For example, malġukipiaq (40) means "two times twenty."

| # | Number | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | iñuiññaq | 20 |

| 40 | malġukipiaq | 2×20 |

| 100 | tallimakipiaq | 5×20 |

| 400 | iñuiññakipiaq | 20×20 |

| 800 | malġuagliaq | 2×400 |

| 8000 | atausiqpak | 8000 |

| 16,000 | malġuqpak | 2×8000 |

Where the Number Words Come From

The word for five, tallimat, comes from the word for "hand" or "arm." The word for ten, qulit, means "top." This refers to the ten fingers on the upper part of the body.

The word for 15, akimiaq, means "it goes across." The word for 20, iñuiññaq, means "entire person" or "complete person." This refers to all 20 fingers and toes on a person.

How Iñupiaq Sentences Work

In Iñupiaq, the basic word order is subject-object-verb. This means the person or thing doing the action comes first. Then comes the thing the action is done to. Finally, the action word (verb) comes last.

However, the word order can be flexible. Sometimes, the subject or object might not even be said if it's clear from the situation.

Iñupiaq grammar also has ways to change verbs. These are called passive, antipassive, causative, and applicative. They change how the action relates to the people or things involved.

Noun Incorporation

A cool thing in Iñupiaq is "noun incorporation." This is when a noun is added right into the verb. It creates a new, longer verb. For example, a noun that tells what tool is used can become part of the verb. This makes the sentence shorter and clearer.

A Sample of Iñupiaq Language

Here is a short text in the Kivalina dialect of Iñupiaq:

Aaŋŋaayiña aniñiqsuq Qikiqtami. Aasii iñuguġuni. Tikiġaġmi Kivaliñiġmiḷu. Tuvaaqatiniguni Aivayuamik. Qulit atautchimik qitunġivḷutik. Itchaksrat iñuuvlutiŋ. Iḷaŋat Qitunġaisa taamna Qiñuġana.

And here is what it means in English:

Aaŋŋaayiña was born in Shishmaref. He grew up in Point Hope and Kivalina. He marries Aivayuaq. They had eleven children. Six of them are alive. One of the children is Qiñuġana.

Comparing Words in Different Dialects

Here's how some words are said in different Iñupiaq dialects:

| North Slope Iñupiaq | Northwest Alaska Iñupiaq (Kobuk Malimiut) |

King Island Iñupiaq | Qawiaraq dialect | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| atausiq | atausriq | atausiq | atauchiq | 1 |

| malġuk | malġuk | maġluuk | malġuk | 2 |

| piŋasut | piñasrut | piŋasut | piŋachut | 3 |

| sisamat | sisamat | sitamat | chitamat | 4 |

| tallimat | tallimat | tallimat | tallimat | 5 |

| itchaksrat | itchaksrat | aġvinikłit | alvinilġit | 6 |

| tallimat malġuk | tallimat malġuk | tallimat maġluuk | mulġunilġit | 7 |

| tallimat piŋasut | tallimat piñasrut | tallimat piŋasut | piŋachuŋilgit | 8 |

| quliŋuġutaiḷaq | quliŋŋuutaiḷaq | qulinŋutailat | quluŋŋuġutailat | 9 |

| qulit | qulit | qulit | qulit | 10 |

| qulit atausiq | qulit atausriq | qulit atausiq | qulit atauchiq | 11 |

| akimiaġutaiḷaq | akimiaŋŋutaiḷaq | agimiaġutailaq | . | 14 |

| akimiaq | akimiaq | agimiaq | akimiaq | 15 |

| iñuiññaŋŋutaiḷaq | iñuiñaġutaiḷaq | inuinaġutailat | . | 19 |

| iñuiññaq | iñuiñaq | inuinnaq | . | 20 |

| iñuiññaq qulit | iñuiñaq qulit | inuinaq qulit | . | 30 |

| malġukipiaq | malġukipiaq | maġluutiviaq | . | 40 |

| tallimakipiaq | tallimakipiaq | tallimativiaq | . | 100 |

| kavluutit, malġuagliaq qulikipiaq | kavluutit | kabluutit | . | 1000 |

| nanuq | nanuq | taġukaq | nanuq | polar bear |

| ilisaurri | ilisautri | iskuuqti | ilichausrirri | teacher |

| miŋuaqtuġvik | aglagvik | iskuuġvik | naaqiwik | school |

| aġnaq | aġnaq | aġnaq | aŋnaq | woman |

| aŋun | aŋun | aŋun | aŋun | man |

| aġnaiyaaq | aġnauraq | niaqsaaġruk | niaqchiġruk | girl |

| aŋutaiyaaq | aŋugauraq | ilagaaġruk | ilagaaġruk | boy |

| Tanik | Naluaġmiu | Naluaġmiu | Naluaŋmiu | white person |

| ui | ui | ui | ui | husband |

| nuliaq | nuliaq | nuliaq | nuliaq | wife |

| panik | panik | panik | panik | daughter |

| iġñiq | iġñiq | qituġnaq | . | son |

| iglu | tupiq | ini | ini | house |

| tupiq | palapkaaq | palatkaaq, tuviq | tupiq | tent |

| qimmiq | qipmiq | qimugin | qimmuqti | dog |

| qavvik | qapvik | qappik | qaffik | wolverine |

| tuttu | tuttu | tuttu | tuttupiaq | caribou |

| tuttuvak | tiniikaq | tuttuvak, muusaq | . | moose |

| tulugaq | tulugaq | tiŋmiaġruaq | anaqtuyuuq | raven |

| ukpik | ukpik | ukpik | ukpik | snowy owl |

| tatqiq | tatqiq | taqqiq | taqqiq | moon/month |

| uvluġiaq | uvluġiaq | ubluġiaq | ubluġiaq | star |

| siqiñiq | siqiñiq | mazaq | machaq | sun |

| niġġivik | tiivlu, niġġivik | tiivuq, niġġuik | niġġiwik | table |

| uqautitaun | uqaqsiun | qaniqsuun | qaniqchuun | telephone |

| mitchaaġvik | mirvik | mizrvik | mirvik | airport |

| tiŋŋun | tiŋmisuun | silakuaqsuun | chilakuaqchuun | airplane |

| qai- | mauŋaq- | qai- | qai- | to come |

| pisuaq- | pisruk- | aġui- | aġui- | to walk |

| savak- | savak- | sawit- | chuli- | to work |

| nakuu- | nakuu- | naguu- | nakuu- | to be good |

| maŋaqtaaq | taaqtaaq | taaqtaaq | maŋaqtaaq, taaqtaaq | black |

| uvaŋa | uvaŋa | uaŋa | uaŋa, waaŋa | I, me |

| ilviñ | ilvich | iblin | ilvit | you (singular) |

| kiña | kiña | kina | kina | who |

| sumi | nani, sumi | nani | chumi | where |

| qanuq | qanuq | qanuġuuq | . | how |

| qakugu | qakugu | qagun | . | when (future) |

| ii | ii | ii'ii | ii, i'i | yes |

| naumi | naagga | naumi | naumi | no |

| paniqtaq | paniqtaq | paniqtuq | pipchiraq | dried fish or meat |

| saiyu | saigu | saayuq | chaiyu | tea |

| kuuppiaq | kuukpiaq | kuupiaq | kuupiaq | coffee |

See also

In Spanish: Idioma iñupiaq para niños

In Spanish: Idioma iñupiaq para niños