Serpentinite facts for kids

Serpentinite is a fascinating type of rock that forms deep inside the Earth. It's mostly made of minerals from the serpentine group. These minerals get their name because the rock often has a texture or color that looks a bit like snake skin! In ancient times, people like the Greek pharmacologist Pedanius Dioscorides (around AD 50) even thought this rock could protect against snakebites.

You might hear serpentinite called "serpentine" or "serpentine rock," especially in older books or everyday conversations. Scientists are very interested in serpentinite because many important chemical reactions needed for life might have happened when this rock formed. This makes places where serpentinite is found a possible "cradle of life" on Earth!

Contents

How Serpentinite Forms

Serpentinite forms when certain types of rocks, usually found deep under the ocean floor, mix with seawater. This process is called serpentinization. Imagine seawater seeping into rocks far below the ocean, especially near mid-ocean ridges (underwater mountain ranges) or where one part of the Earth's crust slides under another. This water changes the original rocks into serpentinite.

Minerals Inside Serpentinite

The main minerals you'll find in serpentinite are antigorite, lizardite, and chrysotile. These are all part of the serpentine subgroup. You'll also often find magnetite, which is a magnetic iron mineral. Sometimes, another mineral called brucite is present too. These minerals are similar in their basic makeup but can look a little different. Small amounts of other minerals, like awaruite and sulfide minerals, can also be found.

Making Hydrogen Gas

During the process of serpentinization, a special reaction can happen that creates hydrogen gas. This happens when iron-rich minerals in the original rock react with water. This hydrogen gas is very important because it can provide energy for tiny living things, called microbes, that live deep underground where there isn't much sunlight.

Underwater Hot Springs and Mud Volcanoes

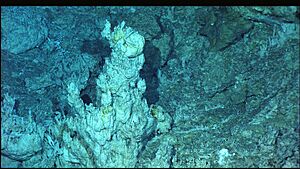

Deep in the ocean, you can find amazing places called hydrothermal vents, which are like underwater hot springs. Some of these vents are found in areas with serpentinite. They release fluids that are rich in unique chemicals, including complex hydrocarbon molecules. The Rainbow field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is one example.

Another incredible place is the Lost City Hydrothermal Field. Here, vents release cooler fluids (around 40 to 75 degrees Celsius) that are very alkaline and rich in magnesium. These vents build tall chimneys, some up to 60 meters high, made of carbonate minerals. These chimneys are home to thriving communities of microbes. Scientists believe that the heat for these vents might come directly from the serpentinization process itself!

In places like the Mariana Trench, there are also large serpentinite mud volcanoes. These erupt serpentinite mud that rises from deep within the Earth's mantle through cracks in the seafloor. Studying these mud volcanoes helps scientists understand how Earth's plates move and interact. The fluids from these mud volcanoes also support unique microbial life.

Where Life Might Have Begun

Many scientists believe that serpentinite thermal vents, like those at the Lost City, could be where life on Earth first began. The chemical reactions that happen during serpentinization are very similar to those needed to create important building blocks for life, like acetyl-CoA. Even the tiny metal clusters found in many enzymes (which help living things work) look like minerals formed in these serpentinite environments. It's a fascinating idea that these rocks might hold the secret to life's origins!

Serpentinite and Nature

Special Soils for Plants

When serpentinite bedrock is close to the surface, it creates a special kind of soil. This soil is often thin and doesn't have much calcium or other important plant nutrients. However, it can have high levels of elements like chromium and nickel, which can be harmful to most plants.

Because of these tough conditions, only certain plants can grow well in serpentine soils. These plants are very special and have adapted to survive where others can't. For example, some species of Clarkia franciscana and certain types of manzanita thrive on serpentinite. Since these areas are often small and isolated, the unique plant communities that live there are like "ecological islands" and are often endangered. However, in places like New Caledonia, plants adapted to serpentine soils are so strong that they can resist new plant species brought in from other places.

Serpentine soils are found all over the world, often in places where ancient ocean crust has been pushed up to the surface. You can find them in the Balkan Peninsula, Turkey, Cyprus, the Alps, Cuba, New Caledonia, and in parts of the Appalachian Mountains and the Pacific Ranges in the United States.

Where to Find Serpentinite

You can find notable serpentinite deposits in many places around the globe. Some well-known locations include Thetford Mines in Quebec, Canada; Lake Valhalla in New Jersey, USA; and Gila County, Arizona, USA. In Europe, it's found in the Lizard complex in Cornwall, England, and in various places in Greece and Italy. Large areas of serpentinite are also part of ophiolites, which are sections of oceanic crust and upper mantle that have been uplifted onto land. Famous ophiolites include the Semail Ophiolite in Oman, the Troodos Ophiolite in Cyprus, and ophiolites in Newfoundland and New Guinea.

How People Use Serpentinite

Beautiful Stone for Buildings and Art

Serpentinite is a relatively soft rock, with a Mohs hardness of 2.5 to 3.5. This means it's quite easy to carve and shape. Because of its beautiful colors and patterns, which can look a bit like marble, serpentinite has been used for centuries as a decorative stone in architecture and art. For example, College Hall at the University of Pennsylvania is built using serpentinite. In Europe, places like the mountainous Piedmont region of Italy and Larissa, Greece, were important sources of this stone. Artists and craftspeople in Zöblitz in Saxony, Germany, have been carving serpentinite for hundreds of years.

Lamps and Tools for the Inuit

The Inuit people and other indigenous groups in the Arctic have traditionally used serpentinite for many purposes. They carved lamps called qulliq or kudlik from serpentinite. These lamps burned oil or fat to provide heat, light, and a way to cook. The Inuit also used serpentinite to make tools and, more recently, beautiful carvings of animals to sell.

-

An Inuit Elder tending a Qulliq, a ceremonial oil lamp made of serpentinite.

Helping Nuclear Power Plants

Serpentinite contains a lot of "bound water," meaning water molecules are part of its mineral structure. This water contains many hydrogen atoms. These hydrogen atoms are good at slowing down tiny particles called neutrons. Because of this, serpentinite can be used in some nuclear reactor designs as a shield to protect people from radiation. For example, in the RBMK series of reactors, like the one at Chernobyl, serpentinite was used for top radiation shielding. It can also be added to special concrete used in reactor shielding to make the concrete denser and better at capturing neutrons.

Cleaning Up Carbon Dioxide

Serpentinite has a special ability to absorb carbon dioxide from the air. This makes it a potential tool for capturing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide, which helps fight climate change. Scientists are exploring ways to speed up this reaction, such as heating serpentinite with carbon dioxide in special reactors. They are also looking into injecting carbon dioxide directly into underground serpentinite formations or using waste from serpentine mines to absorb CO2. Serpentinite could even be a source of magnesium for technologies that scrub CO2 from the air.

See Also

- Hydrogen cycle

- Nephrite

- Soapstone

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |