Magnetite facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Magnetite |

|

|---|---|

Magnetite from Bolivia

|

|

| General | |

| Category |

|

| Formula (repeating unit) |

iron(II,III) oxide, Fe2+Fe3+ 2O 4 |

| Strunz classification | 4.BB.05 |

| Crystal symmetry | Fd3m (no. 227) |

| Unit cell | a = 8.397 Å; Z = 8 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Black, gray with brownish tint in reflected sun |

| Crystal habit | Octahedral, fine granular to massive |

| Crystal system | Isometric |

| Twinning | On {Ill} as both twin and composition plane, the spinel law, as contact twins |

| Cleavage | Indistinct, parting on {Ill}, very good |

| Fracture | Uneven |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 5.5–6.5 |

| Luster | Metallic |

| Streak | Black |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| Specific gravity | 5.17–5.18 |

| Solubility | Dissolves slowly in hydrochloric acid |

| Major varieties | |

| Lodestone | Magnetic with definite north and south poles |

Magnetite is a special mineral that's one of the main sources of iron ore. Its chemical formula is Fe2+Fe3+

2O

4. It's part of the iron oxide family and is known for being ferrimagnetic. This means it's strongly attracted to a magnet and can even be turned into a permanent magnet itself! Besides super rare natural native iron, magnetite is the most magnetic mineral found naturally on Earth.

Imagine ancient people discovering pieces of naturally magnetized magnetite, called lodestone. These pieces could attract small bits of iron, which is how they first learned about magnetism!

Magnetite usually looks black or brownish-black with a shiny, metallic surface. It's pretty hard, scoring 5 to 6.5 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, and it leaves a black streak when you rub it on a rough surface. You can find tiny grains of magnetite commonly in igneous (volcanic) and metamorphic rocks (rocks changed by heat and pressure).

Its scientific chemical name is iron(II,III) oxide, but it's also sometimes called ferrous-ferric oxide.

Contents

Where Does Magnetite Come From?

Besides igneous rocks, magnetite also shows up in sedimentary rocks. These include huge layers called banded iron formations and in lake and ocean sediments. It can be found as tiny grains washed in by water or even as magnetofossils, which are tiny magnetic bits made by living things! Scientists also think tiny magnetite particles form in soils, though they quickly change into another mineral called maghemite.

Structure

The chemical makeup of magnetite is Fe2+(Fe3+)2(O2-)4. This means it contains two types of iron: ferrous (Fe2+) and ferric (Fe3+). This mix tells us that magnetite forms in places with a medium amount of oxygen. Scientists figured out its detailed structure way back in 1915, making it one of the first crystal structures ever studied using X-ray diffraction.

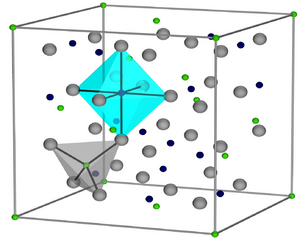

Magnetite has a special structure called an inverse spinel. Imagine oxygen atoms forming a repeating pattern, and the iron atoms fit into the spaces between them. Half of the Fe3+ atoms fit into small, four-sided spaces (tetrahedral sites), while the other half, along with all the Fe2+ atoms, fit into larger, eight-sided spaces (octahedral sites). A single repeating unit of this structure, called a unit cell, contains 32 oxygen atoms and is about 0.839 nanometers long.

Because of its structure, magnetite can mix with other similar minerals to form "solid solutions." Two examples are ulvospinel (Fe

2TiO

4) and magnesioferrite (MgFe

2O

4). When magnetite mixes with ulvospinel, it forms something called titanomagnetite, which is common in many volcanic rocks.

How Magnetite Crystals Look

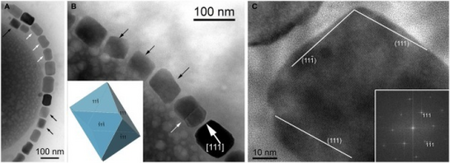

Natural and lab-made magnetite usually forms as octahedral crystals, which look like two pyramids joined at their bases. Sometimes, they can also form as rhombic-dodecahedra, which have 12 diamond-shaped faces. Crystals can also grow together in a special way called twinning.

Scientists can grow magnetite crystals in the lab, sometimes as large as 10 millimeters across!

Magnetite's Reactions and Earth's History

Magnetite is super important for understanding how rocks form. It can react with oxygen to create hematite. This pair of minerals acts like a "buffer," helping scientists figure out how much oxygen was around when the rocks formed. This is called the hematite-magnetite (HM) buffer.

Magnetite also helps us understand the Earth's magnetic field over time. The way magnetite and other iron minerals react with oxygen affects how well magnetite can record the Earth's ancient magnetic field. This field changes over time, and studying magnetite helps us learn about plate tectonics and how our planet has evolved.

Magnetite's Magnetic Superpowers

As mentioned, lodestone (naturally magnetic magnetite) was used as an early form of magnetic compass. Magnetite is also a key tool in paleomagnetism, the study of Earth's past magnetic field. This science is vital for understanding how plate tectonics works.

Magnetite has a special property called the Verwey transition. At very cold temperatures (around -153°C or 120 K), its crystal structure changes, affecting its electrical and magnetic properties. It also has a Curie temperature of about 580°C (1076°F). Above this temperature, magnetite loses its strong magnetic properties.

If there's a lot of magnetite in an area, it can be detected using aeromagnetic surveys, where planes fly with special magnetometers to measure magnetic forces.

Melting Point of Magnetite

Solid magnetite particles melt at very high temperatures, usually between 1583–1597°C (2881–2907°F).

Where Can We Find Magnetite?

Magnetite is sometimes found in large amounts in beach sand, especially in places like Hong Kong, California, and New Zealand. These "black sands" are formed when magnetite, eroded from rocks, is carried to the beach by rivers and then concentrated by ocean waves and currents.

Huge deposits of magnetite are also found in banded iron formations. These ancient sedimentary rocks are like time capsules, helping scientists understand how the amount of oxygen in Earth's atmosphere changed over billions of years.

Other big magnetite deposits are in places like Chile, Uruguay, Sweden, Australia, and the Adirondack Mountains in New York, USA. Even an entire mountain in Mauritania, called Kediet ej Jill, is made of magnetite! There's also a massive deposit in Spain that was mined for many years. In Peru, there are even sand dunes made of magnetite-rich sand, some over 2,000 meters tall!

If there's a lot of magnetite in an area, it can even affect compass navigation. In Tasmania, Australia, for example, there are so many magnetic rocks that compasses can get confused, requiring extra care when navigating.

While rare, magnetite crystals can sometimes form in a cubic shape, like those found in New York and Sweden. This unusual shape might happen when other elements like zinc are present during its formation.

Magnetite can also be found in fossils, formed by living organisms, and even in meteorites from space!

Magnetite in Living Things

Biomagnetism is the study of how living things interact with magnetic fields, often because they have tiny crystals of magnetite inside them. These crystals are found in many organisms, from tiny magnetotactic bacteria to animals, including humans!

Pure magnetite particles are created by some magnetotactic bacteria in special structures called magnetosomes. These magnetosomes are like tiny compasses, helping the bacteria navigate using Earth's magnetic field. When these bacteria die, their magnetite particles can be preserved in sediments as magnetofossils.

Some birds, like pigeons, have magnetite crystals in their upper beak. This, along with other special cells in their eyes, might help them sense the Earth's magnetic field, giving them a kind of built-in GPS for migration!

Chitons, which are a type of sea mollusk, have a special tongue-like structure called a radula with teeth coated in magnetite. The hardness of the magnetite helps them scrape and break down food.

Scientists can even use biological magnetite to learn about an organism's past, like where it migrated or how Earth's magnetic field changed over time.

Magnetite in Your Brain?

Yes, tiny amounts of magnetite can be found in different parts of the human brain, including areas related to memory and movement. Iron in the brain can exist as magnetite, in blood (hemoglobin), or in a protein called ferritin.

However, too much magnetite can be harmful because it can create harmful molecules called free radicals, which are linked to cell damage. Some research suggests that the buildup of iron and magnetite might be connected to brain conditions like Alzheimer's disease.

Scientists are still trying to understand the full role of magnetite in the brain. Some even wonder if humans have a magnetic sense, like birds, though this is still being researched.

Interestingly, electron microscope scans can tell the difference between magnetite produced by our own bodies (which looks jagged) and magnetite from air pollution (which looks rounded and like tiny nanoparticles). This pollution-related magnetite, often from burning fuels, can travel to the brain through the nose. In some studies, pollution-borne magnetite particles outnumbered natural ones by a lot, and these particles might be linked to brain problems.

Cool Uses for Magnetite

Because it's so rich in iron, magnetite has been a major iron ore for a long time. It's processed in huge furnaces to make pig iron or sponge iron, which are then turned into steel.

Magnetic Recording

Did you know that early magnetic recording tapes, developed in the 1930s, used magnetite powder? Later, they switched to a different iron oxide, but magnetite was there at the beginning!

Catalysis

Magnetite is super important in making fertilizers! About 2-3% of the world's energy is used for the Haber Process, which turns nitrogen into ammonia for fertilizers. This process relies on catalysts made from magnetite. The magnetite is carefully processed to create a very porous material with a large surface area, which makes it an excellent catalyst.

Tiny Magnetite Particles

Magnetite micro- and nanoparticles are used in many cool ways, from medicine to cleaning up the environment.

- Water Purification: Imagine tiny magnetite nanoparticles added to dirty water. They can stick to pollutants like bacteria or even radioactive particles. Then, using a strong magnet, these particles (with the attached pollutants) can be pulled out, cleaning the water! The magnetite can even be reused.

- Drug Delivery: These tiny magnetic particles can be used to create ferrofluids. In medicine, ferrofluids can help deliver drugs directly to a specific part of the body. For example, in cancer treatment, drug molecules attached to magnetic particles could be guided by a magnet to the tumor, treating only that area and reducing side effects for the rest of the body. Ferrofluids are also used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology.

Coal Mining Industry

In the past, magnetite was used in coal mining to separate coal from waste rock. Coal is lighter than rock, so by putting them in a liquid mixture of water and magnetite (which has an intermediate density), the coal would float, and the heavier rocks would sink.

Magnetene

Magnetene is a new, super-thin, two-dimensional material made from magnetite. It's special because it has extremely low friction, meaning things can slide over it very easily.

Gallery

-

Octahedral crystals of magnetite up to 1.8 cm across, on cream colored feldspar crystals, locality: Cerro Huañaquino, Potosí Department, Bolivia

-

Magnetite in contrasting chalcopyrite matrix

-

Magnetite with a rare cubic habit from St. Lawrence County, New York

See also

In Spanish: Magnetita para niños

In Spanish: Magnetita para niños

- Bluing (steel), a process that uses magnetite to protect steel from rust

- Corrosion product

- Ferrite

- Greigite

- Magnesia (sometimes found with magnetite)

- Mill scale

- Magnes the shepherd (legendary discoverer of magnetism)

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |