Wolastoq facts for kids

The Wolastoq (which means Saint John River; in French, Fleuve Saint-Jean) is a long river, about 418 miles (673 km) (673 km) long. It starts in the Notre Dame Mountains near the border between Maine and Quebec. From there, it flows through New Brunswick before reaching the northwest shore of the Bay of Fundy.

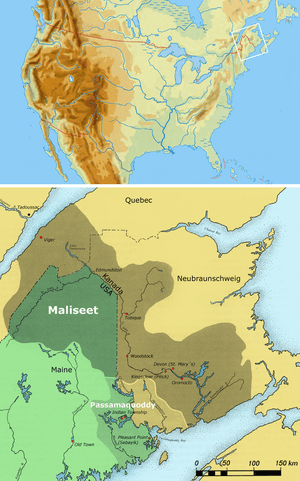

For a long time, this river and all the smaller streams that flow into it were the home of the Wolastoqiyik and Passamaquoddy First Nations. Before Europeans arrived, these groups lived and traveled along the river. The Wolastoq was very important because it was one of the best ways to travel for First Nations people who were moving away from English settlements along the Atlantic coast of North America. After the English won battles in the French and Indian War, the Wolastoqiyik and their Acadian friends moved upriver. They even created a small, independent area called the Republic of Madawaska in the remote upper part of the river. People living there didn't want to be part of either Canada or the United States. This changed when the current Canada–United States border was set by the Webster–Ashburton Treaty in 1842.

Today, the lower part of the river has farms and industries. However, the part of the river in the United States, upstream from Madawaska, is still mostly wild and empty. This area is known as the North Maine Woods. Because Madawaska was so isolated for many years, the special Acadian French language spoken there has been kept alive.

Contents

First Nations and the River

The First Nations people living in eastern North America, like those in New England and the Maritimes, spoke different dialects of the Algonquin language. Often, there were slight differences in how people spoke depending on whether they lived far up a river or closer to the coast and where the river met the ocean.

The Passamaquoddy people hunted sea animals along the northwest shore of the Bay of Fundy. They spoke a dialect that the Wolastoqiyik people could understand. The Wolastoqiyik were hunters who lived inland along the upper Saint John River and its smaller streams. The Wolastoqiyik called themselves "people of the beautiful river" because the river was their home and they used canoes to travel for hunting, fishing, and trading.

In the early 1500s, French fishermen started trading furs with the First Nations. This made people more interested in the smaller streams and headwaters of the river, even though not many animals lived there, so fewer people lived in those areas. After spending the winter hunting and trapping in the forests, the villages of Ouigoudi (at the mouth of the river) and Aukpaque (where boats could no longer go) became popular gathering places in the summer. This is where they met European fur traders.

Sadly, the fur traders also brought European diseases. These diseases greatly reduced the Wolastoqiyik population, which was estimated to be less than a thousand by 1612. While the fur traders' arrival had a devastating impact, some intermarriage between First Nations people and Europeans over time helped some people develop a bit more resistance to these new diseases.

European Settlers Arrive

Before Europeans even started building settlements in North America, English and French fur traders were already competing with each other. Ouigoudi, the village at the river's mouth, was made stronger and called Fort La Tour. Aukpaque became known as Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas when Acadian colonists settled in the lower river valley.

The First Nations people generally liked the fur traders more than the later settlers. This was because the settlers started taking their land and stopping them from using it for hunting and gathering food, which was how they had always lived. The pressure from settlers was not as strong along the Saint John River. This was because the cold water from the Gulf of Maine made the growing season shorter here compared to places like Massachusetts or the Nova Scotia peninsula, which were closer to the warmer Gulf Stream.

The first Acadians were descendants of French sailors and shipbuilders. They focused on fishing, trading, and repairing boats, rather than just farming. This meant they didn't need as much land, which helped them get along better with the First Nations. These Acadians kept good relationships with the First Nations. When King Philip's War started, the Wolastoqiyik joined the Wabanaki Confederacy to fight against New England.

The Wolastoqiyik became strong allies of the Acadians during the later French and Indian Wars. The Saint John River valley became the last place where Acadians refused to promise loyalty to the British king. About a thousand Wolastoqiyik people helped protect a hundred Acadian families who moved up the Saint John River. They were trying to escape the Acadian Expulsion, when the British forced many Acadians to leave their homes. During the St. John River campaign, British soldiers killed farm animals and burned Acadian settlements as far upstream as Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas.

The Border Dispute

After the American Revolutionary War, many Loyalist refugees (people who supported the British) moved to Saint John at the mouth of the river. Others settled in Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas, which was renamed Fredericton.

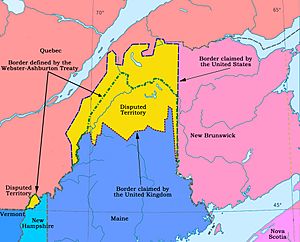

At the end of the war, the Saint Croix River became the border along the Atlantic coast. This meant the Saint John River stayed in Canada, while the Penobscot River was given to Massachusetts. The Treaty of Paris (1783) said that the eastern border of Massachusetts would be a line drawn straight north from the source of the Saint Croix River to the area where water flows into the Saint Lawrence River.

However, the English people who signed the treaty hadn't fully explored the river's headwaters because of ongoing conflicts with the Wolastoqiyik. This caused problems. First, it wasn't clear which stream was truly the source of the Saint Croix River. Second, the Saint John River doesn't flow straight south, as they might have thought, unlike better-mapped rivers like the Hudson and Connecticut River.

Canada was also worried because they discovered how close the water divide was to the south bank of the Saint Lawrence River. This left Canada with a very narrow strip of land that was difficult to build a road on. Such a road was important to connect Atlantic Canada to Quebec during the winter when the Saint Lawrence River was frozen. Because of this, Canada believed the treaty meant that the entire Saint John River area should stay under Canadian control. Meanwhile, surviving Acadian and Wolastoqiyik people continued to resist British rule. They moved upriver to the Acadian Landing Site west of the Saint Croix border, where other Acadian refugees from Quebec joined them.

After Maine became independent from Massachusetts in 1820, lumbermen from Maine encouraged these refugees to form the independent Republic of Madawaska. These lumbermen also started changing the flow of the Saint John headwaters so that logs could be floated down the Penobscot River to sawmills in Bangor. These actions led to a clearer border being set by the Webster–Ashburton Treaty in 1842. This treaty gave the north bank of the Saint John River west of the Saint Croix to Canada, in exchange for some land further west.

The River Today

Today, the Trans-Canada Highway follows the path of the road the English had wanted to build along the north bank of the river, through the area that was once disputed. Most of the Saint John River area on the disputed south bank became Aroostook County, Maine. The town of Madawaska there still shares the Acadian French language with Edmundston across the river.

The Allagash River and the Baker Branch of the Saint John River (upstream from Madawaska) flow through the mostly empty North Maine Woods. These forests, mainly made of black spruce trees, were a major source of pulpwood (wood used to make paper) for Maine's paper mills throughout the 1900s. Because these areas were far from Maine cities, landowners often hired lumberjacks from Quebec. Édouard Lacroix came up with new ways to transport wood from the river's headwaters. For example, he built a road from Lac-Frontière, Quebec to create the isolated Eagle Lake and West Branch Railroad in 1927, and the Nine Mile Bridge over the river in 1931.

More and more people are using the upper river for fun activities like canoeing. This has led to parts of it being protected, like the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. People also recognize that the river supports special plant communities that are rarely seen anywhere else. When snow melts in the spring, the rushing water and ice can scrape the riverbanks, leaving bedrock covered by thin, acidic soil. This unique environment supports one of the highest numbers of rare plants in Maine, including plants like Clinton's bulrush, Dry Land Sedge, Mistassini primrose, Nantucket shadbush, Northern Painted Cup, and Swamp Birch.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Río Saint John (bahía de Fundy) para niños

In Spanish: Río Saint John (bahía de Fundy) para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |