History of New England facts for kids

New England is a very old part of the United States. People started settling here over 150 years before the American Revolution. The first English colony in New England was Plymouth Colony, started in 1620 by Pilgrims. They came from England to escape religious problems. Plymouth was the second English colony in America, after Jamestown. Many Puritans also moved to this area between 1620 and 1640, especially around Boston and Salem.

The economy grew with farming, fishing, and cutting timber. Whaling (hunting whales) and sea trading were also important. New England writers and events helped start the American War of Independence. This war began when British soldiers and Massachusetts fighters clashed in the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

By the 1840s, New England was a main center for the movement against slavery. It was also a leader in American literature and higher education. The Industrial Revolution in America started here, with many textile mills and machine shops by 1830. For much of the 1800s, New England was the manufacturing center of the United States. It played a big role during and after the American Civil War, pushing for an end to slavery and for civil rights.

In the 1900s, manufacturing moved to other parts of the U.S. New England faced a tough time with its economy. But by the early 2000s, the region became a hub for technology, making weapons, scientific research, and money services.

Contents

- Native Peoples of New England

- Colonial Era in New England

- First European Settlements (1607–1620)

- Plymouth Colony (1620–1643)

- Massachusetts Puritans

- Other New England Colonies

- Early Colonial Conflicts

- The Dominion of New England (1686–1689)

- Later Colonial Wars

- Colonial Government

- New England's Character

- Population Growth

- Colonial Economy

- Education in Colonial New England

- New England: 1770-1900

- New England Since 1900

- Famous Leaders from New England

- Images for kids

Native Peoples of New England

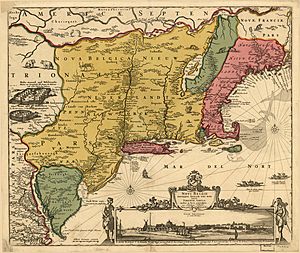

New England has been home to Algonquian-speaking native peoples for a long time. These groups include the Abenaki, Penobscot, Pequot, and Wampanoag, among others. In the 1400s and 1500s, European explorers like Giovanni da Verrazzano and John Cabot mapped the New England coast. They called the area Norumbega, after a legendary native city.

The earliest known people in New England were Native Americans who spoke different Eastern Algonquian languages. Some important tribes were the Abenaki, Penobscot, Pequot, Mohegans, Pocumtuck, and Wampanoag. Before Europeans arrived, the Western Abenakis lived in New Hampshire, Vermont, and parts of Maine and Quebec. Their main town was Norridgewock in Maine. The Penobscot lived along the Penobscot River in Maine. The Wampanoag lived in southeastern Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket. The Pocumtucks lived in Western Massachusetts. The Connecticut River Valley connected many native groups.

Archaeological finds show that native people in warmer parts of Southern New England started farming over a thousand years ago. They grew corn, tobacco, kidney beans, squash, and Jerusalem artichoke. They likely traded with Algonquian peoples in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, where the growing season was shorter.

Around 1600, French, Dutch, and English traders came to the New World. They traded metal, glass, and cloth for beaver furs. These traders and sailors also brought new European diseases like smallpox and measles. These diseases spread quickly and killed most Native Americans in the region by the 1630s.

Colonial Era in New England

First European Settlements (1607–1620)

In 1606, King James I of England gave permission for two companies to start colonies in America. These were the Virginia Company of London and the Virginia Company of Plymouth. Their goal was to claim land for England and trade. The London Company successfully started the Jamestown Colony in Virginia in 1607.

Captain John Smith explored the New England coast in 1614. He named the region "New England" in his book, A Description of New England.

Plymouth Colony (1620–1643)

The name "New England" became official on November 3, 1620. This happened when the Virginia Company of Plymouth's charter was replaced by a new one for the Plymouth Council for New England. This was a company set up to colonize and govern the area.

In December 1620, the Pilgrims started a permanent settlement called Plymouth Colony in what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts. They were English religious separatists who came on the ship Mayflower. They held a special feast of thanks, which became part of the American tradition of Thanksgiving. Plymouth was a small colony and was later joined with Massachusetts in 1691.

In 1638, a strong earthquake shook all of New England. It was the first earthquake recorded in the region.

Even early on, relations between English colonists and native peoples became difficult. Trade with Europeans had already weakened native groups due to diseases. The supply of furs also ran out, making hunters go into other tribes' lands. This caused more tension. As English colonists settled permanently, they took land and tried to make native peoples follow Puritan laws. This made the situation worse.

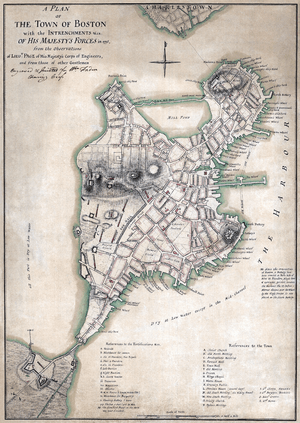

Massachusetts Puritans

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was founded in 1628, and its main city, Boston, was started in 1630. The Puritans were a much larger group than the Pilgrims. They started the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629 with 400 settlers. They wanted to change the Church of England by creating a new, pure church in America. By 1640, 20,000 Puritans had arrived. Many died, but others found a healthy climate and plenty of food.

The Puritans created a very religious and close-knit culture. They hoped this new land would be a "City upon a Hill"—a very religious community to be an example for Europe.

Other New England Colonies

Roger Williams believed in religious freedom and separating church and state. He was sent away from Massachusetts for his ideas. He led a group south to found Providence in 1636. This settlement joined with others to form the Rhode Island Colony. It became a safe place for Baptists, Quakers, and others who disagreed with the Puritans, like Anne Hutchinson.

On March 3, 1636, the Connecticut Colony was given permission to start its own government. The nearby New Haven Colony later joined Connecticut.

Vermont was not settled by Europeans at this time. The areas of New Hampshire and Maine were governed by Massachusetts.

Early Colonial Conflicts

Relationships between colonists and Native Americans were sometimes peaceful and sometimes involved fighting. The bloodiest conflict was the Pequot War in 1636, which included the Mystic massacre. Six years later, Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, New Haven, and Connecticut colonies formed the New England Confederation. This group was meant to help with defense, but it was not very effective and soon fell apart.

In 1675, King Philip's War broke out. Colonists and their Native American allies fought against a widespread Native American uprising. There were massacres and killings on both sides. The colonists won in the south, but had to sign peace treaties in the north (present-day New Hampshire and Maine).

The Dominion of New England (1686–1689)

In 1686, King James II was worried about the colonies becoming too independent. He created the Dominion of New England, which combined all the New England colonies under one rule. Later, New York and New Jersey were added. The colonists did not like this union because it took away their elected leaders. In 1687, when Connecticut refused to give up its charter, Governor Edmund Andros tried to take it by force. Legend says the colonists hid the charter in the Charter Oak tree. Andros's efforts to control the colonies did not work well. After King James II was removed from power in the Glorious Revolution of 1689, Andros was arrested by the colonists and sent back to England.

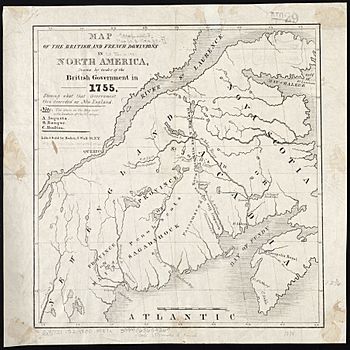

Later Colonial Wars

From 1688 to 1763, there were six colonial wars mainly between Great Britain and New France. New England was allied with the Iroquois Confederacy, and New France was allied with the Wabanaki Confederacy. After the British took over Acadia (now Nova Scotia) in 1710, they claimed that land. But present-day New Brunswick and most of Maine were still fought over. During the final French and Indian War, New Englanders forced the Acadians out of Nova Scotia. After Britain won the war in 1763, the Connecticut River Valley opened up for settlement in western New Hampshire and Vermont.

Colonial Government

After the Glorious Revolution in 1689, most colonial charters changed. Royal Governors were appointed to almost every colony. There was often tension between these governors and the elected local officials. Governors wanted more power, but local officials resisted. Town governments often kept running as they had before, ignoring the Royal Governors when possible. This tension eventually led to the American Revolution. The colonies did not formally unite again until 1776, when they declared themselves independent states in the United States.

New England's Character

New England is the only North American region (besides Nova Scotia) named after a kingdom in the British Isles. It has kept much of its unique character, especially its historic sites. Its name reminds us of the past, even though many original English-Americans have moved further west.

Population Growth

About 30,000 settlers came to New England between 1620 and 1640. This time is called "The Great Migration". Not many more people immigrated until the Irish arrived in the 1840s and 1850s because of the potato famine.

The region's economy grew fast in the 1600s. This was due to many immigrants, high birth rates, low death rates, and lots of cheap farmland. The population grew from 3,000 in 1630 to 91,000 in 1700. After 1643, fewer than fifty immigrants arrived each year. Families were large, with an average of 7.1 children between 1660 and 1700.

By 1770, just before the Revolution, almost one million people lived in New England. Most were descendants of the first settlers. Their high birth rate meant the population doubled every 25 years. Their shared beliefs and background made them a very similar group of settlers in America. This high birth rate continued for another century. In the 1700s and early 1800s, New England was seen as a very distinct part of the country, just as it is today. During the War of 1812, some people in New England talked about leaving the Union. This was because New England merchants opposed the war with their main trading partner, Great Britain.

After the American Revolutionary War, Connecticut and Massachusetts gave land to the federal government. This land was in the Northwest Territory and the Western Reserve.

Colonial Economy

New England colonies were mostly settled by farmers who grew enough food for themselves. Later, with the help of the Puritan work ethic and wealthier English colonists, New England's economy focused on crafts and trade. This was different from the Southern colonies, which relied more on farming for export.

The Puritan economy was based on self-sufficient farms. They traded only for things they could not make themselves. New England generally had a higher economic standing and better living standards than the Chesapeake region. Besides farming, fishing, and logging, New England became an important center for trade and shipbuilding. It was a hub for trading between the southern colonies and Europe.

The region's economy grew steadily throughout the colonial era. This happened even though it lacked a main crop to export. All the colonies and many towns tried to boost the economy. They did this by supporting projects like roads, bridges, inns, and ferries. They also gave money or special rights to sawmills, grist mills, iron mills, and other businesses. Most importantly, colonial governments created laws that helped businesses. They resolved disputes, enforced contracts, and protected property rights. Hard work and starting new businesses were common. Puritans and Yankees believed in the "Protestant Work Ethic", which encouraged hard work as part of their religious duty.

New England traded a lot within the English empire in the mid-1700s. They sent pickled beef and pork, onions, potatoes, and codfish to the Caribbean. They also sent wood for sugar and molasses containers.

Benjamin Franklin noted in 1772 that in New England, almost everyone owned property. He said they had a vote, lived in good homes, had plenty of food and fuel, and wore clothes often made by their own families.

The benefits of growth were shared widely. Even farm workers were better off by the end of the colonial period. The growing population led to less good farmland for young families. This caused people to marry later or move to new lands further west. In towns and cities, there was strong business activity and more specialized jobs. Wages for men steadily increased before 1775. New jobs opened for women, like weaving, teaching, and tailoring. The region bordered New France, and during wars, the British spent a lot of money buying supplies, building roads, and paying colonial soldiers. Coastal ports focused on fishing, international trade, and shipbuilding. After 1780, whaling became important. These factors helped the economy grow, even without new technology.

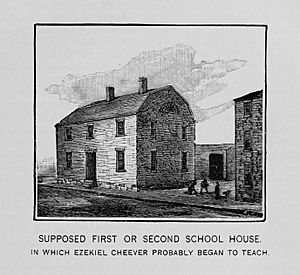

Education in Colonial New England

New England has always been very important in American education. The first American schools in the thirteen colonies opened in the 1600s. Boston Latin School was founded in 1635. It is the first public school and the oldest existing school in the United States.

Colonists first taught children at home, through the church, and by apprenticeships. Schools later became key for teaching social skills. Basic reading and math were often taught at home if parents knew them. Literacy rates were much higher in New England than in the South. By the mid-1800s, schools took on many tasks traditionally done by parents.

All New England colonies required towns to set up schools, and many did. In 1642, the Massachusetts Bay Colony made "proper" education required. Other New England colonies followed. These early schools were mostly for boys, with few options for girls. In the 1700s, "common schools" appeared. These had students of all ages taught by one teacher in one room. They were supported by local towns but were not free. Families paid tuition or "rate bills."

Larger towns in New England opened grammar schools, which were like early high schools. The most famous was the Boston Latin School, which is still a public high school today. Hopkins School in New Haven, Connecticut, was another. By the 1780s, most had been replaced by private academies. By the early 1800s, New England had a network of elite private high schools, now called "prep schools." Examples include Phillips Andover Academy (1778) and Phillips Exeter Academy (1781). They became coeducational in the 1970s and are still very respected today.

Colleges

Harvard College was founded by the colonial government in 1636. It was named after an early supporter, John Harvard. Most of the money came from the colony. Harvard first focused on training young men for the ministry.

Yale College was founded in 1701 and moved to New Haven, Connecticut, in 1716. Conservative Puritan ministers in Connecticut were unhappy with Harvard's more liberal ideas. They wanted their own school to train orthodox ministers. Dartmouth College, started in 1769, grew from a school for Native Americans. It moved to Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1770. Brown University was founded by Baptists in 1764.

Girls' Education

Tax-supported schooling for girls began as early as 1767 in New England. It was optional, and some towns were slow to adopt it. For example, Northampton, Massachusetts, was late because rich families did not want to pay taxes to help poor families. Northampton taxed all households to support a grammar school for boys going to college. Girls were not publicly educated there until after 1800. In contrast, Sutton, Massachusetts, had diverse leaders and religions early on. Sutton paid for its schools by taxing only households with children. This created support for education for both boys and girls.

Historians note that reading and writing were different skills back then. Schools taught both. But in places without schools, reading was mainly taught to boys and a few privileged girls. Men handled public affairs and needed to read and write. Girls mainly needed to read religious materials. This explains why colonial women could often read but not write their names, using an "X" instead.

New England: 1770-1900

American Revolution

New England, especially Boston, was the center of revolutionary activity before 1775. Massachusetts politicians like Samuel Adams, John Adams, and John Hancock were leaders. New Englanders were proud of their political freedoms and local democracy. They felt the British government was threatening these. Their main complaint was about taxes. Colonists argued that only their own local governments could tax them, not the British Parliament. Their cry was, "No taxation without representation!"

On December 16, 1773, a ship was bringing taxed tea to Boston. Local activists called the Sons of Liberty dressed as Native Americans. They raided the ship and dumped all the tea into the harbor. This event, known as the Boston Tea Party, angered British officials. The King and Parliament decided to punish Massachusetts.

Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts in 1774. These laws brought harsh punishment. They closed the port of Boston, which was vital for the economy. They also ended self-government, putting people under military rule. The patriots set up a shadow government. The British Army attacked them on April 18, 1775, at Concord. On April 19, in the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the famous "shot heard 'round the world" was fired. British troops were forced back into Boston by local militias. The British army only controlled Boston, and it was quickly surrounded. The Continental Congress took charge of the war. General George Washington was sent to lead. He forced the British to leave Boston in March 1776. After that, the main fighting moved south. However, the British made raids along the coast and briefly took parts of Rhode Island and Maine. Overall, patriots controlled 99 percent of New England's population.

New England's Dark Day happened on May 19, 1780. The sky became so dark that people needed candles in the middle of the day. It seems that forest fires, fog, and cloud cover all caused this darkness.

Early National Period

Ending Slavery

After gaining independence, New England was no longer a single political unit. But it remained a distinct historical and cultural region of its now-independent states. By 1784, all states in the region had started to gradually end slavery. Vermont ended it completely in 1777, and Massachusetts in 1783. During the War of 1812, some New England merchants talked about leaving the Union. They had just recovered financially and opposed the war with Britain, their biggest trading partner. Delegates from New England met in Hartford in 1814-15 for the Hartford Convention. They discussed changes to the U.S. Constitution to protect the region and keep its political power.

In 1820, as part of the Missouri Compromise, Maine, which was part of Massachusetts, became a state. Today, New England always includes the six states: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

For the rest of the period before the Civil War, New England remained unique. In politics, it often went against the rest of the country. Massachusetts and Connecticut were among the last places where the Federalist Party was strong. When the Second Party System began in the 1830s, New England became the strongest area for the new Whig Party. Whigs were usually powerful across New England, except in Maine and New Hampshire, which were more Democratic. Important leaders like Daniel Webster came from this region.

New England and areas settled by New Englanders, like Upstate New York and parts of the Midwest, became the center of the strongest anti-slavery feelings in the country. Abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison were New Englanders. The region was home to anti-slavery politicians like John Quincy Adams and Charles Sumner. When the anti-slavery Republican Party formed in the 1850s, all of New England became strongly Republican. It stayed that way until the early 1900s, when immigration led some lower New England states to become more Democratic.

Growth of Cities

New England became the most urbanized part of the country. In 1860, 32 of the 100 largest cities in the U.S. were in New England. It was also the most educated region. Many famous writers and thinkers of the time were New Englanders. These included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Industrial Revolution

New England was an early center of the Industrial Revolution. In Beverly, Massachusetts, the first cotton mill in America was founded in 1787. This Beverly Cotton Manufactory was the largest cotton mill of its time. Its advancements led to other mills, like Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

Towns like Lawrence, Massachusetts, Lowell, Massachusetts, and Lewiston, Maine became famous for their textile industries. Textile manufacturing grew quickly, leading to a shortage of workers. Mill owners hired people to bring young women and children from the countryside to work in factories. Between 1830 and 1860, thousands of farm girls came to work in the mills. They left home to help their families, save for marriage, and see more of the world. They also left due to population growth on farms, seeking opportunities in growing New England cities. Travel by stagecoach and railroad made it easier for workers to move from country to city. Most female workers came from rural farming towns in northern New England.

As the textile industry grew, so did immigration. The number of Irish workers in the mills increased, and the number of young American women working there decreased. At first, the mills employed young Yankee farm women. Then they used Irish and French immigrants.

Changes in Agriculture

As New England's economy changed with industry, so did its farming. Around 1790, most New England farms grew just enough food for themselves. Farmers grew crops like wheat, corn, beans, and squash. There wasn't a big local market to sell extra crops. So, farmers didn't have a reason to grow more than they needed. This meant they also made their own furniture, clothes, and soap.

By 1850, farming in New England was very different. It became specialized, producing many new and different products. Two main reasons for this change were:

- The rise of manufacturing in New England (industrialization).

- Competition from farms in the western states.

Industrial jobs in New England's towns and cities created a growing urban population that didn't farm. Farmers finally had a nearby market to sell their crops. This allowed them to earn money beyond what they grew for their own use. Farms became more productive and specialized in certain crops. What factories or people wanted to buy now decided what each farm grew. Products like potash, charcoal, and fuel wood were produced more. Some farms even grew tobacco, which was mostly a southern crop, in central Connecticut and northern Massachusetts. Many farming groups formed to share information on new tools like the cast-iron plow and mowing machines.

Another important result of the manufacturing boom was the availability of cheap products. For example, new mills made inexpensive textiles. It became cheaper for farm women to buy these fabrics than to make them at home. Women then found new jobs elsewhere, often in the mills, where there was a worker shortage. They started earning cash incomes.

Competition from western states also shaped New England agriculture. Better transportation, like railroads and steamboats, made it easier to bring western goods to New England. This competition led to a decline in local pork, cattle, and wheat production. New England farmers then focused on goods that western farmers couldn't easily compete with. These included milk, butter, potatoes, and broomcorn. So, both industrial growth and western competition led to specialized farming in New England.

The changes in New England's economy in the mid-1800s were huge. They were similar to the rapid economic growth seen in Korea and Taiwan after World War II. The big changes in agriculture were a key part of this economic shift.

The CSS Tallahassee disrupted shipping to New England in August 1864.

There have been waves of immigration to New England from Ireland, Quebec, Italy, Portugal, Asia, Latin America, Africa, and other parts of the United States.

French Canadians

Many French-Canadians from rural Canada moved to New England textile mills after 1850. About 600,000 people from French-speaking Canada moved to the U.S., especially to New England.

The first migrants went to nearby Vermont and New Hampshire. But as textile factories hired more people, the main destination from the late 1870s to the early 1900s was southern Massachusetts. Many of these immigrants wanted short-term jobs to earn money and return home. However, about half of them stayed permanently. By 1900, 573,000 French Canadians had immigrated to New England. They were the second largest group of immigrants after the Irish.

These new Franco-Americans often lived together in neighborhoods called Little Canada. After 1960, these neighborhoods faded. There were few French language institutions other than Catholic churches. Some French newspapers existed, but they had only about 50,000 readers in 1935. The generation that grew up during World War II often avoided French education for their children and insisted they speak English. By 1976, most Franco-Americans spoke English, and many felt that the younger generation had lost touch with their heritage.

New England Since 1900

Railroads

The New Haven railroad was the main train company in New England from 1872 to 1968. J. P. Morgan, a leading banker, was interested in New England's economy. Starting in the 1890s, Morgan began funding major New England railroads, like the New Haven and the Boston and Maine. He arranged for them not to compete with each other. In 1903, he brought in Charles Sanger Mellen as president of the New Haven.

Morgan's goal was to buy and combine the main railway lines in New England. He wanted to merge their operations, lower costs, electrify busy routes, and modernize the system. With less competition and lower costs, he expected higher profits. The New Haven bought 50 smaller companies, including streetcars, freight ships, passenger ships, and a network of electric trolleys. By 1912, the New Haven operated over 2,000 miles of track with 120,000 employees. It almost completely controlled traffic from Boston to New York City.

Morgan's desire for a monopoly angered reformers during the Progressive Era. One notable critic was Boston lawyer Louis Brandeis, who fought the New Haven for years. Mellen's harsh methods upset the public and led to high costs for buying companies and building new lines. The accident rate went up when they tried to save money on maintenance. The company's debt grew from $14 million in 1903 to $242 million in 1913. Also in 1913, the federal government sued them for being a monopoly, forcing them to give up their trolley systems.

The rise of cars, trucks, and buses after 1910 greatly reduced the New Haven's profits. The line went bankrupt in 1935. It was reorganized and made smaller, but went bankrupt again in 1961. In 1969, it merged into the Penn Central system, which also went bankrupt. Parts of the system are now part of Conrail.

The car revolution happened much faster than anyone expected, especially railroad leaders. In 1915, Connecticut had 40,000 cars. Five years later, it had 120,000. Truck growth was even faster.

Weather Events

In the 1930s and 1940s, there were winter "outing clubs" in New England. These clubs held dog sled races, ski jumping, cross-country competitions, and dances.

The 1938 New England hurricane hit the region hard, killing about 700 people. The U.S. Weather Bureau made a mistake in its forecast, so there was little warning. Many thousands of houses and buildings were damaged or destroyed. Local relief efforts were weak, so federal agencies took over. This led to the creation of the modern disaster relief system. The hurricane blew down 15 million acres of trees, which was one-third of New England's total forest at the time. Much of the older trees in the region today are about 75 years old, dating from after this storm.

Modern Economy

New England's economy changed greatly after World War II. The factory economy almost disappeared. Textile mills closed one by one from the 1920s to the 1970s. For example, the Crompton Company went bankrupt in 1984 after 178 years in business, costing 2,450 jobs. The main reasons were cheap imports, a strong dollar, fewer exports, and a failure to adapt. The shoe industry followed.

What remains is very high-tech manufacturing. This includes jet engines, nuclear submarines, medicines, robotics, scientific tools, and medical devices. MIT (the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) created a model for how universities and industries work together in high-tech fields. It led to many software and hardware companies, some of which grew very fast. By the 2000s, New England became known for its leadership in education, medicine, medical research, high-technology, finance, and tourism.

Famous Leaders from New England

Eight presidents of the United States were born in New England. However, only five are usually linked with the area:

- John Adams (Massachusetts)

- John Quincy Adams (Massachusetts)

- Franklin Pierce (New Hampshire)

- Calvin Coolidge (born in Vermont, linked with Massachusetts)

- John F. Kennedy (Massachusetts)

Nine vice presidents of the United States were born in New England. Again, only five are usually linked with the area:

- John Adams

- Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts)

- Hannibal Hamlin (Maine)

- Henry Wilson (born in New Hampshire, linked with Massachusetts)

- Chester A. Arthur

- Calvin Coolidge

Eleven Speakers of the United States House of Representatives have been elected from New England. These include:

- Jonathan Trumbull, Jr. (Connecticut)

- Theodore Sedgwick (Massachusetts)

- Joseph Bradley Varnum (Massachusetts)

- Robert Charles Winthrop (Massachusetts)

- James G. Blaine (Maine)

- Thomas Brackett Reed (Maine)

- Frederick Gillett (Massachusetts)

- Joseph William Martin, Jr. (Massachusetts)

- John William McCormack (Massachusetts)

- Tip O'Neill (Massachusetts)

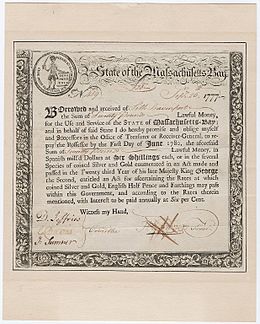

Images for kids

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |