Elbridge Gerry facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

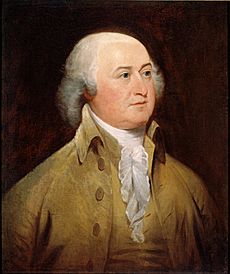

Elbridge Gerry

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Nathaniel Jocelyn

|

|

| 5th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1813 – November 23, 1814 |

|

| President | James Madison |

| Preceded by | George Clinton |

| Succeeded by | Daniel D. Tompkins |

| 9th Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office June 10, 1810 – June 5, 1812 |

|

| Lieutenant | William Gray |

| Preceded by | Christopher Gore |

| Succeeded by | Caleb Strong |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 3rd district |

|

| In office March 4, 1789 – March 3, 1793 |

|

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Shearjashub Bourne Peleg Coffin Jr. |

| Member of the Congress of the Confederation | |

| In office June 30, 1783 – September 1785 |

|

| Member of the Continental Congress from Massachusetts |

|

| In office February 9, 1776 – February 19, 1780 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Elbridge Thomas Gerry

July 17, 1744 Marblehead, Province of Massachusetts Bay, British America |

| Died | November 23, 1814 (aged 70) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 10 |

| Education | Harvard University (BA and MA) |

| Signature | |

Elbridge Gerry (born July 17, 1744 – died November 23, 1814) was an important American leader during the country's early years. He was a Founding Father, a businessman, a politician, and a diplomat. He served as the fifth Vice President under President James Madison from 1813 until he passed away in 1814. The political term "gerrymandering" is named after him.

Gerry came from a wealthy family. He strongly disagreed with British rules in the 1760s. He helped organize resistance during the American Revolutionary War. He was elected to the Second Continental Congress. There, he signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation.

In 1787, he attended the Constitutional Convention. However, he was one of only three people who refused to sign the Constitution. He felt it did not protect individual rights enough. He wanted a Bill of Rights to be included. After the Constitution was approved, he was elected to the first United States Congress. He played a key role in writing and passing the Bill of Rights. He always supported individual freedoms and states' rights.

Gerry initially disliked political parties. He had friends on both sides of the political divide, between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. He was part of a group sent to France, but the trip went poorly in what was called the XYZ Affair. Federalists blamed him for the problems. After this, Gerry became a Democratic-Republican. He tried several times to become Governor of Massachusetts before winning in 1810.

During his second term as governor, new state voting districts were created. These districts were shaped strangely, which led to the word "gerrymander." He lost the next election. In 1812, he was chosen as Vice President and won the election. He was older and not in good health. Gerry served for 21 months before he died in office. He is the only person who signed the Declaration of Independence to be buried in Washington, D.C.

Contents

- Elbridge Gerry's Early Life and Education

- Starting His Political Career

- Serving in Congress During the Revolution

- The Constitutional Convention

- Serving in the U.S. House of Representatives

- The XYZ Affair

- Serving as Governor of Massachusetts

- Vice Presidency and Death

- Elbridge Gerry's Legacy

- Images for kids

- See also

Elbridge Gerry's Early Life and Education

Elbridge Gerry was born on July 17, 1744. His hometown was Marblehead, Massachusetts, a town on the North Shore. His father, Thomas Gerry, was a successful merchant who owned ships. His mother, Elizabeth Gerry, was the daughter of a wealthy Boston merchant. Elbridge was the third of their five children who lived to adulthood.

He was taught by private tutors at home. He then went to Harvard College just before he turned 14. He earned his first degree in 1762 and a master's degree in 1765. After college, he joined his father's shipping business. By the 1770s, the Gerry family was among the richest merchants in Massachusetts. They traded with places like Spain and the West Indies.

Starting His Political Career

Gerry quickly became a strong opponent of the British government's taxes on the American colonies. These taxes began after the French and Indian War ended in 1763. In 1770, he joined a committee in Marblehead. This group worked to stop British goods from being imported if they were taxed. He often talked with other Massachusetts leaders who opposed British rule, like Samuel Adams and John Adams.

In May 1772, he was elected to the Massachusetts legislative assembly. There, he worked closely with Samuel Adams to fight British policies. He helped set up Marblehead's committee of correspondence. These committees helped colonies communicate and organize against British rule.

After the Boston Port Act closed Boston's port in 1774, Marblehead became an important port for delivering aid. Gerry, as a leading merchant and Patriot, helped store and deliver supplies to Boston. He was elected to the First Continental Congress in September 1774 but did not attend due to his father's death.

Serving in Congress During the Revolution

Gerry was elected to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in 1774. This group formed after the British governor closed the regular assembly. He joined the committee of safety. This committee made sure that weapons and gunpowder stayed out of British hands. His actions helped hide weapons in Concord. These hidden supplies were the target of the British raid that started the American Revolutionary War in April 1775.

During the Siege of Boston, Gerry continued to supply the new Continental Army. He used his business contacts in France and Spain to get weapons and other supplies. He also helped transfer money from Spain to Congress. He sent ships to ports all along the American coast. He even helped fund private ships (privateers) to attack British shipping.

Gerry served in the Second Continental Congress from 1776 to 1780. During this time, the war was the main focus. He helped convince delegates to support the Declaration of Independence in 1776. John Adams praised Gerry, saying he was crucial for America's freedom. Gerry was known for his honesty and strong beliefs. He always believed in a limited central government. He also thought that civilians should control the military.

He consistently held these views throughout his career. He only changed his mind slightly after Shays' Rebellion in 1786–87, when he saw a need for a stronger central government. He also disliked the idea of political parties. He stayed somewhat independent from both the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties for a long time. It wasn't until 1800 that he officially joined the Democratic-Republicans. He felt the Federalists were trying to give too much power to the national government.

In 1780, he left the Continental Congress. He turned down offers to return or to join the state senate. He believed he could do more good in the state's lower house. In 1781, he became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Gerry returned to the Confederation Congress in 1783. He served there until 1785. In 1786, he married Ann Thompson, who was 20 years younger than him. They had ten children between 1787 and 1801. The war made Gerry wealthy. He sold his merchant businesses and started investing in land. In 1787, he bought a large property in Cambridge, Massachusetts, called Elmwood. This became his family home.

The Constitutional Convention

Gerry played a big part in the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. He strongly believed that state governments and the federal government should have clear, separate powers. He thought state legislatures should choose federal officials. His views against direct popular elections were partly shaped by Shays' Rebellion. However, he also wanted to protect individual freedoms by limiting government power.

He supported the idea that the Senate should have an equal number of members from each state. This idea was adopted in the Connecticut Compromise. Gerry also suggested that senators should vote as individuals, not as a single vote for their state. He opposed the Three-fifths Compromise. This compromise counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a person for representation in the House of Representatives. Gerry was against slavery and said the Constitution should not support it.

Because he worried about leaders misleading the public, Gerry also supported indirect elections. He didn't succeed in getting them for the House of Representatives. But he did get indirect elections for the Senate, where state legislatures chose members. He also suggested many ways for the President to be elected indirectly, often involving state governors and electors.

Gerry was unhappy that the proposed Constitution did not list specific individual freedoms. He also generally opposed ideas that made the central government stronger. He was one of only three delegates who voted against the proposed Constitution. He worried that the convention didn't have the power to make such big changes. He also felt the Constitution lacked "federal features." In the end, Gerry refused to sign because he was concerned about citizens' rights and the government's power to raise armies and taxes.

Debates and the Bill of Rights

After the convention, Gerry continued to oppose the Constitution in its original form. He wrote a letter explaining his objections, which was widely shared. His main concern was the lack of a Bill of Rights. However, he also said he would accept the Constitution if some changes were made. Supporters of the Constitution criticized him in the press.

Because of the controversy, he was not chosen as a delegate to the Massachusetts meeting that would decide on the Constitution. However, he was later invited to attend. The leaders of this meeting were mostly Federalists, and Gerry was not given a chance to speak officially. He left after a heated argument. Massachusetts approved the Constitution by a close vote. This debate caused Gerry to become distant from some friends.

Serving in the U.S. House of Representatives

In 1788, opponents of the Federalists nominated Gerry for governor. But he lost to the popular John Hancock. After the Constitution was approved, Gerry changed his mind about it. He noted that other states had asked for amendments that he supported. Friends nominated him for a seat in the first House of Representatives, even though he didn't want to run. He served two terms.

In June 1789, Gerry suggested that Congress look at all the proposed changes to the Constitution. These changes had been requested by various states. He led the opposition to some proposals, arguing they didn't go far enough to protect individual freedoms. He successfully pushed for freedom of assembly to be included in the First Amendment. He also helped create the Fourth Amendment, which protects against unfair searches and seizures. He tried, but failed, to add the word "expressly" to the Tenth Amendment. This would have limited the federal government's power even more.

He successfully worked to limit the federal government's control over state militias. He had also argued against a large standing army, saying it could be dangerous.

Gerry strongly supported Alexander Hamilton's plans for public money. This included the government taking on state debts. He also supported Hamilton's Bank of the United States. These views matched his earlier calls for a stronger national economy. He spoke out in the House against anything that seemed to threaten republican ideals. He generally opposed laws that he felt limited individual and state freedoms. He did not want executive officers to have too much power. He specifically opposed creating the Treasury Department because its head might become too powerful. He wanted the legislature to have more power over appointments.

Gerry did not run for re-election in 1792. He went home to raise his children and care for his wife, who was often ill. He agreed to be a presidential elector for John Adams in the 1796 election. During Adams's time as president, Gerry stayed friends with both Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson. He hoped this divided leadership would lead to less conflict. However, the split between Federalists (Adams) and Democratic-Republicans (Jefferson) grew wider.

The XYZ Affair

President Adams chose Gerry to be part of a special group sent to France in 1797. Tensions were high between the two countries. France saw the Jay Treaty (between the U.S. and Great Britain) as a sign of an Anglo-American alliance. So, France started seizing American ships. Adams picked Gerry, even though his cabinet disagreed. Adams said Gerry was one of the "two most impartial men in America."

Gerry joined Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and John Marshall in France in October 1797. They met briefly with the French Foreign Minister, Talleyrand. A few days later, three French agents (called "X," "Y," and "Z" in official papers) demanded large bribes from the Americans before talks could continue. The Americans refused. Talleyrand then focused on Gerry, believing he was the easiest to work with. He pushed Pinckney and Marshall out of the talks. They left France in April 1798. Gerry wanted to leave too, but Talleyrand threatened war if he did. Gerry refused to make any major deals and left Paris in August.

By then, news of the failed talks had reached the United States. Many Americans called for war. An undeclared naval war, the Quasi-War (1798–1800), followed. Federalists accused Gerry of supporting the French and causing the talks to fail. But Adams and Republicans like Thomas Jefferson supported him. The negative news hurt Gerry's reputation. People even burned his image in protest outside his home. He was later cleared when his letters with Talleyrand were published in 1799. Because of the Federalist attacks and his belief that their military buildup threatened American values, Gerry officially joined the Democratic-Republican Party in 1800. He then ran for Governor of Massachusetts.

Serving as Governor of Massachusetts

For many years, Gerry tried to become governor of Massachusetts but lost. His opponent, Caleb Strong, was a popular Federalist. The Federalist party controlled Massachusetts politics, even though the country was leaning towards the Republicans. In 1803, Republicans in Massachusetts were divided, and Gerry only had support from certain regions. He decided not to run in 1804. He also faced financial problems because he had guaranteed a loan for his brother that was due. This issue hurt Gerry's finances for the rest of his life.

Republican James Sullivan won the governor's seat in 1807. But his successor lost to Federalist Christopher Gore in 1809. Gerry ran again in 1810 against Gore and won by a small margin. Republicans painted Gore as a British-loving "Tory" who wanted to bring back the monarchy. They called Gerry a patriotic American. Federalists called Gerry a "French partisan." A temporary reduction in the threat of war with Britain helped Gerry win. The two ran against each other again in 1811, and Gerry won again after a very tough campaign.

Gerry's first year as governor was calmer because Federalists controlled the state senate. He urged for calm in political discussions, saying it was important for the nation to be united against foreign powers. In his second term, with Republicans controlling the legislature, he became more partisan. He removed many Federalist officials from state government. The legislature also changed the court system, creating more judicial jobs, which Gerry filled with Republicans. However, arguments within his own party and a lack of qualified candidates caused problems. Federalists complained loudly about these partisan changes.

Other laws passed during Gerry's second year included a bill to add more members to Harvard's Board of Overseers. This was to make its religious membership more diverse. Another law made religious taxes more flexible. The Harvard bill had a political side because a recent split between different religious groups also divided the state along party lines.

In 1812, the state drew new voting district lines as required by the constitution. The Republican-controlled legislature created district boundaries to help their party win more state and national offices. This led to some strangely shaped districts. Even though Gerry was not happy about these very partisan districts, he signed the law. A local Federalist newspaper compared the shape of one state senate district in Essex County to a salamander. They called it a "Gerry-mander." Since then, creating such oddly shaped districts to gain political advantage has been called gerrymandering.

Gerry also investigated Federalist newspapers for potentially slandering him. This further hurt his popularity with moderate voters. The redistricting controversy, the libel investigation, and the upcoming War of 1812 all contributed to Gerry's defeat in 1812. He lost to Caleb Strong, whom the Federalists had brought out of retirement. However, the gerrymandering of the state Senate was successful for Republicans. They strongly controlled that body, even though Federalists won the house and the governor's seat.

Vice Presidency and Death

After losing the 1812 election, Gerry's financial problems led him to ask President James Madison for a federal job. He was chosen by his party to be Madison's vice presidential running mate in the 1812 presidential election. He was seen as a safe choice who would attract votes from the North. Madison narrowly won re-election, and Gerry took office in March 1813. At that time, the Vice President's job was not very active. Gerry's duties included supporting the administration's plans in Congress and giving out government jobs in New England.

On November 23, 1814, Gerry became very ill while visiting the Treasury Department. He died soon after returning home. He is buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. He is the only person who signed the Declaration of Independence to be buried in the nation's capital. He left his wife and children land, but not much cash. However, he had managed to pay off his brother's debts with his salary as Vice President. At 68 years old when he became Vice President, he was the oldest person to hold that office until 1929.

Elbridge Gerry's Legacy

Gerry is mainly remembered for the word "gerrymander," for not signing the United States Constitution, and for his part in the XYZ Affair. His political journey has been seen as complex. Early writers found it hard to explain why his views seemed to change. However, some historians believe Gerry was always a strong supporter of republicanism, which was the original idea for the American government. They also think his role in the Constitutional Convention greatly influenced the final document.

Gerry had ten children, and nine of them lived to adulthood. His grandson, Elbridge Thomas Gerry, became a famous lawyer and giver of money to good causes in New York. His great-grandson, Peter G. Gerry, served in the U.S. House of Representatives and later as a U.S. Senator from Rhode Island.

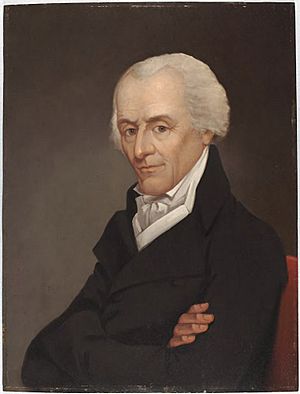

Gerry is shown in two paintings by John Trumbull: the Declaration of Independence and General George Washington Resigning His Commission. Both paintings are displayed in the rotunda of the United States Capitol.

The towns of Elbridge and Gerry in upstate New York are believed to be named after him. The town of Phillipston, Massachusetts was first named Gerry in his honor in 1786. But its name was changed in 1812 because of local disagreements about the War of 1812.

Gerry's Landing Road in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is near the Eliot Bridge and his former home, Elmwood. In the 1800s, this area was known as Gerry's Landing. The house believed to be his birthplace, the Elbridge Gerry House, still stands in Marblehead. Marblehead's Elbridge Gerry School is also named after him.

Images for kids

-

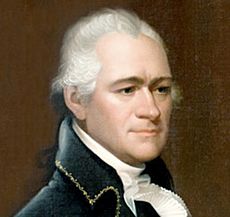

Ann Thompson, Elbridge Gerry's wife.

See also

In Spanish: Elbridge Gerry para niños

In Spanish: Elbridge Gerry para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |