1796 United States presidential election facts for kids

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

138 members of the Electoral College 70 electoral votes needed to win |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 20.1% |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

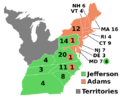

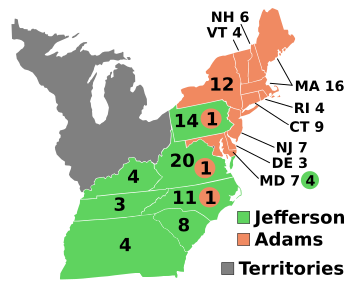

Presidential election results map. Green denotes states won by Jefferson and burnt orange denotes states won by Adams. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes cast by each state.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1796 United States presidential election was the third time Americans voted for their president. It happened between November 4 and December 7, 1796. This election was special for a few reasons:

- It was the first time two main candidates truly competed for the presidency.

- Political parties became very important for the first time.

- It was the only time a president and vice president were chosen from different political parties.

In this election, John Adams from the Federalist Party won. He was the current Vice President. He defeated Thomas Jefferson from the Democratic-Republican Party, who had been the Secretary of State.

President George Washington decided not to run for a third term. This meant that for the first time, political parties openly competed for the top job. The Federalists supported John Adams. The Democratic-Republicans supported Thomas Jefferson.

Back then, the rules for elections were different. Each member of the Electoral College cast two votes. They did not say which vote was for president and which was for vice president. The person with the most votes became president. The person who came in second became vice president. This is why Adams and Jefferson, from different parties, ended up working together.

The election campaign was very intense. Federalists tried to link Democratic-Republicans to the violence of the French Revolution. Democratic-Republicans accused Federalists of wanting a king and a government controlled by rich people. They also linked Adams to policies made by Alexander Hamilton. They felt these policies favored Great Britain too much and made the national government too strong.

Democratic-Republicans were also upset about the Jay Treaty. This treaty created a temporary peace with Great Britain. Federalists, on the other hand, attacked Jefferson's character. They claimed he was an atheist and had been a coward during the American Revolutionary War. Adams' supporters also said Jefferson was too friendly with France. This idea was made stronger when the French ambassador publicly supported Jefferson just before the election. Even with all this fighting, neither Adams nor Jefferson actively campaigned for themselves.

John Adams won the election with 71 electoral votes. This was just one more vote than he needed to win. He won all the votes from New England and many votes from the Mid-Atlantic states. Thomas Jefferson received 68 electoral votes and became the Vice President. Thomas Pinckney, a Federalist, got 59 electoral votes. Aaron Burr, a Democratic-Republican, received 30 electoral votes. Other candidates shared the remaining 48 votes. This election showed the start of the First Party System. It also created a rivalry between Federalist New England and the Democratic-Republican South. The middle states like New York and Maryland often decided who won.

Contents

Who Ran for President?

Since George Washington was stepping down, both major parties wanted their candidate to win. Before the 12th Amendment was added in 1804, electors voted for two people. They didn't say which vote was for president and which was for vice president. The person with the most votes became president, and the second-place person became vice president.

Because of this rule, both parties had several candidates running. These extra candidates were like today's running mates. But back then, they were all technically running for president. The idea was for some electors to vote for the main candidate (like Adams or Jefferson) and then for a different person, not the main running mate. This would make sure the main candidate got more votes than their running mate.

Federalist Candidates

The Federalists chose John Adams from Massachusetts. He was the current Vice President and a key leader during the American Revolution. Most Federalist leaders saw Adams as the natural person to follow Washington.

Adams' main running mate was Thomas Pinckney. He was a former governor of South Carolina. Pinckney had helped make the Treaty of San Lorenzo with Spain. Pinckney agreed to run after Patrick Henry, who was the first choice for many, said no.

Alexander Hamilton, another important Federalist, secretly tried to help Pinckney win more votes than Adams. He asked some electors who supported Jefferson to give their second vote to Pinckney. However, Hamilton still preferred Adams over Jefferson. He told Federalist electors to vote for both Adams and Pinckney.

{{gallery mode="packed" heights="140" File:Official Presidential portrait of John Adams (by John Trumbull, circa 1792).jpg|John Adams,

Vice President File:Thomas Pinckney.jpg|Thomas Pinckney,

Former Governor of South Carolina File:OliverEllsworth.jpg|Oliver Ellsworth,

U.S. Chief Justice

from Connecticut File:John Jay (Gilbert Stuart portrait).jpg|John Jay,

Governor of New York File:JamesIredell.jpg|James Iredell,

Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

from North Carolina File:NC-Congress-SamuelJohnston.JPG|Samuel Johnston,

Former U.S. Senator from North Carolina File:CharlesCPinckney crop.jpg|Charles Cotesworth Pinckney,

U.S. Minister to France

from South Carolina }}

Democratic-Republican Candidates

The Democratic-Republicans supported Thomas Jefferson. He had been the Secretary of State. Jefferson helped start the party with James Madison to oppose Hamilton's policies.

Democratic-Republican leaders in Congress also wanted to agree on one vice-presidential candidate. Jefferson was most popular in the South. So, many leaders wanted a candidate from the North to be his running mate. Some popular choices were Senator Pierce Butler from South Carolina and three New Yorkers: Senator Aaron Burr, Chancellor Robert R. Livingston, and former Governor George Clinton.

In June 1796, a group of Democratic-Republican leaders met. They decided to support Jefferson for president and Burr for vice president.

{{gallery mode="packed" heights="140" File:ThomasJeffersonStateRoomPortrait.jpg|Thomas Jefferson,

former Secretary of State File:Burr (cropped 3x4).jpg|Aaron Burr,

U.S. Senator from New York File:Samuel Adams by John Singleton Copley.jpg|Samuel Adams,

Governor of Massachusetts File:George Clinton by Ezra Ames (full portrait).jpg|George Clinton,

Former Governor of New York }}

Election Results

Tennessee became a state after the 1792 election. This increased the number of electors in the Electoral College to 138.

As mentioned, before the 1804 Twelfth Amendment, electors voted for two people for president. The person who came in second became vice president. Each party tried to get their main candidate to have slightly more votes than their running mate. This was hard to do because all electoral votes were cast on the same day. Communication between states was very slow back then.

There were also rumors that Alexander Hamilton tried to convince Southern electors, who were supposed to vote for Jefferson, to give their second vote to Pinckney. He hoped this would make Pinckney president instead of Adams.

The main campaigning happened in important "swing states" like New York and Pennsylvania. Adams and Jefferson together received 139 electoral votes from the 138 electors. The Federalists won every state north of the Mason-Dixon line, except Pennsylvania. However, one Pennsylvania elector did vote for Adams. Democratic-Republicans won most of the votes in the Southern states. But Maryland and Delaware electors mostly voted for Federalists. North Carolina and Virginia each gave one electoral vote to Adams.

Most electors voted for Adams and another Federalist, or for Jefferson and another Democratic-Republican. But there were some exceptions. One elector in Maryland voted for both Adams and Jefferson. Two electors even voted for George Washington, who wasn't running. Pinckney received the second votes from most electors who voted for Adams. However, 21 electors from New England and Maryland voted for other candidates, like Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth.

Those who voted for Jefferson were less united in their second choice. But Burr got the most second votes among Jefferson's electors. All eight electors in Pinckney's home state of South Carolina voted for Jefferson and Pinckney. At least one Pennsylvania elector also voted this way. In North Carolina, Jefferson won 11 votes, but the other 13 votes were split among six different candidates. In Virginia, most electors voted for Jefferson and Governor Samuel Adams of Massachusetts.

In the end, Adams got 71 electoral votes. This was one more than he needed to become president. If just two of the three Adams electors in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina had voted differently, the outcome could have changed. Jefferson received 68 votes, which was nine more than Pinckney. So, Jefferson became Vice President. Burr finished far behind with 30 votes. Nine other candidates shared the remaining 48 electoral votes. If Pinckney had received all the second votes from New England electors who voted for Adams, he could have been president.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a), (b), (c) | Electoral vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| John Adams | Federalist | Massachusetts | 35,726 | 53.4% | 71 |

| Thomas Jefferson | Democratic-Republican | Virginia | 31,115 | 46.6% | 68 |

| Thomas Pinckney | Federalist | South Carolina | — | — | 59 |

| Aaron Burr | Democratic-Republican | New York | — | — | 30 |

| Samuel Adams | Democratic-Republican | Massachusetts | — | — | 15 |

| Oliver Ellsworth | Federalist | Connecticut | — | — | 11 |

| George Clinton | Democratic-Republican | New York | — | — | 7 |

| John Jay | Federalist | New York | — | — | 5 |

| James Iredell | Federalist | North Carolina | — | — | 3 |

| George Washington | Independent | Virginia | — | — | 2 |

| John Henry | Federalist | Maryland | — | — | 2 |

| Samuel Johnston | Federalist | North Carolina | — | — | 2 |

| Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | Federalist | South Carolina | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 66,841 | 100.0% | 276 | ||

| Needed to win | 70 | ||||

Source (Popular Vote):

Source (Popular Vote): A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825

Source (Electoral Vote):

(a) Votes for Federalist electors have been assigned to John Adams and votes for Democratic-Republican electors have been assigned to Thomas Jefferson.

(b) Only 9 of the 16 states used any form of popular vote.

(c) Those states that did choose electors by popular vote had widely varying restrictions on suffrage via property requirements.

| Popular vote | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams | 53.4% | |||

| Jefferson | 46.6% | |||

| Electoral vote | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| J. Adams | 51.4% | |||

| Jefferson | 49.3% | |||

| Pinckney | 42.8% | |||

| Burr | 21.7% | |||

| S. Adams | 10.9% | |||

| Ellsworth | 8.0% | |||

| Clinton | 5.1% | |||

| Others | 10.9% | |||

How Electoral Votes Were Divided by State

The original Constitution allowed each elector two votes for president. To win, a candidate needed a majority of all electors' votes. Out of 138 electors, 70 voted for Adams and another person. 67 voted for Jefferson and another person. One elector from Maryland voted for both Adams and Jefferson. This brought their totals to 71 for Adams and 68 for Jefferson.

Because both parties' electors split their second votes, Jefferson ended up with more votes than Adams' intended running mate, Thomas Pinckney. This made Jefferson the Vice President-elect.

| State | Electors | Electoral votes |

JA | TJ | TP | AB | SA | OE | GC | JJ | JI | JH | SJ | GW | CP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 9 | 18 | 9 | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | 5 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Delaware | 3 | 6 | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Georgia | 4 | 8 | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Kentucky | 4 | 8 | — | 4 | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Maryland | 10 | 20 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | — | — | — |

| Massachusetts | 16 | 32 | 16 | — | 13 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | — | 2 | — | — |

| New Hampshire | 6 | 12 | 6 | — | — | — | — | 6 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| New Jersey | 7 | 14 | 7 | — | 7 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| New York | 12 | 24 | 12 | — | 12 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| North Carolina | 12 | 24 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 6 | — | — | — | — | 3 | — | — | 1 | 1 |

| Pennsylvania | 15 | 30 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 13 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 8 | 4 | — | — | — | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| South Carolina | 8 | 16 | — | 8 | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tennessee | 3 | 6 | — | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Vermont | 4 | 8 | 4 | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Virginia | 21 | 42 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 15 | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | 1 | — |

| TOTAL | 138 | 276 | 71 | 68 | 59 | 30 | 15 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| TO WIN | 70 | ||||||||||||||

Source: A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825

How Popular Votes Were Counted by State

It's hard for historians to find exact popular vote numbers for early elections. This is because voting rules were very different back then. People didn't vote directly for a presidential candidate. Instead, they voted for people who would represent their state in the Electoral College.

These candidates for elector didn't always say which party they belonged to. They also didn't always say who they planned to vote for. In some areas, candidates from the same party ran against each other. In other places, support for candidates was mixed, causing states to split their electoral votes. All these things make it hard to know exactly what voters wanted. Also, some old voting records are now lost. This means the total popular vote numbers in this article are not complete.

The table below shows the popular vote for each state. It compares the votes for the most popular Adams elector to the most popular Jefferson elector.

| John Adams Federalist |

Thomas Jefferson Democratic-Republican |

Margin | State total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Electoral votes |

# | % | Electoral votes |

# | % | Electoral votes |

# | % | # |

| Connecticut | 9 | no popular vote | 9 | no popular vote | — | — | — | |||

| Delaware | 3 | no popular vote | 3 | no popular vote | — | — | — | |||

| Georgia | 4 | 2,109 | 30.7 | — | 4,759 | 69.3 | 4 | -2,650 | -38.6 | 6,868 |

| Kentucky | 4 | no data | — | no data | 4 | — | — | |||

| Maryland | 10 | 7,466 | 53.5 | 7 | 6,490 | 46.5 | 4 | 976 | 7.0 | 13,956 |

| Massachusetts | 16 | incomplete data | 16 | incomplete data | — | — | — | |||

| New Hampshire | 6 | 3,265 | 89.3 | 6 | 393 | 10.7 | — | 2,872 | 78.6 | 3,658 |

| New Jersey | 7 | no popular vote | 7 | no popular vote | — | — | — | |||

| New York | 12 | no popular vote | 12 | no popular vote | — | — | — | |||

| North Carolina | 12 | no data | 1 | no data | 11 | — | — | |||

| Pennsylvania | 15 | 12,101 | 49.5 | 1 | 12,333 | 50.5 | 14 | -232 | 1.0 | 24,434 |

| Rhode Island | 4 | no popular vote | 4 | no popular vote | — | — | — | |||

| South Carolina | 8 | no popular vote | — | no popular vote | 8 | — | — | |||

| Tennessee | 3 | no popular vote | — | no popular vote | 3 | — | — | |||

| Vermont | 4 | no popular vote | 4 | no popular vote | — | — | — | |||

| Virginia | 21 | 2,156 | 37.3 | 1 | 3,618 | 62.7 | 20 | -1,462 | -25.4 | 5,774 |

| TOTALS | 138 | 27,097 | 49.5 | 71 | 27,593 | 50.5 | 68 | 496 | 1.0 | 54,690 |

| TO WIN | 70 | |||||||||

Sources: Vote Archive; Dubin, p. xii.

States with Close Results

Some states had very close election results:

- Pennsylvania: The winner's margin was less than 5% (1.0% or 232 votes). This state had 15 electoral votes.

- Maryland: The winner's margin was less than 10% (7.0% or 976 votes). This state had 11 electoral votes.

What Happened After the Election?

The four years after this election were the only time in U.S. history that the president and vice president were from different political parties. This created a unique situation in the government.

On January 6, 1797, a representative named William Loughton Smith suggested a change to the Constitution. He wanted electors to clearly state which candidate was for president and which was for vice president. This idea was not acted upon. This lack of action set the stage for problems in the election of 1800.

How Foreign Countries Tried to Influence the Election

The French foreign minister, Charles Delacroix, wanted France to influence the American election. He wrote that France "must raise up the [American] people and at the same time conceal the lever by which we do so." He suggested sending orders to the French ambassador in Philadelphia. The ambassador was told to do everything he could to cause a "successful revolution" and replace George Washington.

The French ambassador to the United States, Pierre Adet, openly supported the Democratic-Republican Party and Thomas Jefferson. He also attacked the Federalist Party and John Adams.

However, France's efforts to interfere did not work. Adams won the election with 71 electoral votes to Jefferson's 68. A big reason why the French failed was George Washington's Farewell Address. In this speech, Washington warned Americans against foreign countries trying to meddle in their politics.

How Electors Were Chosen in Each State

The U.S. Constitution, in Article II, Section 1, said that each state legislature would decide how to choose its electors. Because of this, different states used different methods:

| Method of choosing electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| Each Elector appointed by the state legislature | Connecticut Delaware New Jersey New York Rhode Island South Carolina Vermont |

| State is divided into electoral districts, with one Elector chosen per district by the voters of that district | Kentucky Maryland North Carolina Virginia |

| Each Elector chosen by voters statewide | Georgia Pennsylvania |

|

Massachusetts |

| Each Elector chosen by voters statewide; however, if no candidate wins majority, the state legislature appoints Elector from top two candidates | New Hampshire |

|

Tennessee

|

See also

In Spanish: Elecciones presidenciales de Estados Unidos de 1796 para niños

In Spanish: Elecciones presidenciales de Estados Unidos de 1796 para niños

- Inauguration of John Adams

- Bibliography of Thomas Jefferson

- History of the United States (1789–1849)

- First Party System

- 1796–97 United States House of Representatives elections

- 1796–97 United States Senate elections

Images for kids

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |