John Day (printer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Day

|

|

|---|---|

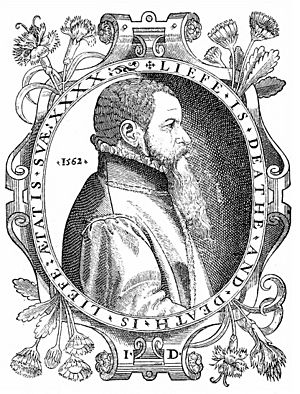

Woodcut of Day (dated 1562) included in the 1563 and subsequent editions of Actes and Monuments

|

|

| Born | c. 1522 |

| Died | 23 July 1584 (aged 61–62) |

| Occupation | Protestant printer |

John Day (also known as Daye) was an English Protestant printer who lived from about 1522 to 1584. He was famous for printing and sharing Protestant books and pamphlets. He made many small religious books, like ABCs, sermons, and translated psalms.

John Day became especially well-known for publishing John Foxe's Actes and Monuments. This book is also called the Book of Martyrs. It was the biggest and most advanced book printed in England during the 1500s.

Day became very successful during the time of Edward VI (1547–1553). Rules for printers were relaxed then. The government encouraged the spread of ideas for the English Reformation. When the Catholic Queen Mary I ruled, many Protestant printers left England. But Day stayed and kept printing Protestant books. In 1554, he was arrested and put in prison. This was likely for printing books that were not allowed.

Under Queen Elizabeth I, Day returned to his printing shop in Aldersgate, London. Important people like William Cecil and Robert Dudley supported him. With their help, he published the Book of Martyrs. He also got special rights to print popular books like The ABC with Little Catechism and The Whole Booke of Psalmes. John Day was very skilled and good at business. He is often called "the master printer of the English Reformation."

Contents

Early Days as a Printer

We don't know much about John Day's early life. Some scholars think he was born in Dunwich, but there's no clear proof. He might have been in London by 1540. His name appears in a city record as a former helper to printer Thomas Raynalde. In 1546, he likely became a free citizen of London. This allowed him to work for the Stringers' Company.

The next year, he started printing with a partner, William Seres. Their shop was in the parish of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate in London. Day and Seres focused on religious books. Many of these were about the religious debates of the time. The Protestant Reformation was growing fast. Laws against printing certain religious books were becoming less strict.

In 1548, ten of the twenty books they printed criticized the Catholic belief of transubstantiation. One book, a poem called Iohn Bon and Mast Person, almost got Day into trouble. Day and Seres also translated important Protestant books from other parts of Europe. For example, they translated Herman von Wied's A Simple and Religious Consultation in 1547.

In 1549, Day opened a new shop in Cheapside. By 1550, he and Seres were successful enough to separate their businesses. Day moved his home and printing shop to Aldersgate. He also switched from the Stringers' Company to the Stationers' Company. Aldersgate was a good place for Day. He could easily find skilled Dutch workers there, who helped him throughout his career.

Day quickly became known as a quality printer. In 1551, he reprinted a detailed edition of the Bible he had made with Seres. The next year, he got a valuable patent. This gave him the right to print books by John Ponet and Thomas Beccon. This made a competitor, Reginald Wolfe, angry. Wolfe already had a patent to print Ponet's Catechism in Latin. They eventually reached a deal. Wolfe could print the Latin Catechism, and Day could print it in English. Day benefited more from this deal. The English versions were used much more widely than the Latin ones. The ABC even started to include Ponet's Catechism.

Printing During Tough Times

John Day had a good reputation as a Protestant printer. He also had connections to important people like John Dudley, William Cecil, and Catherine Willoughby. His career seemed set for success. However, Queen Mary became queen in 1553. The religious situation in England changed completely.

For many years, people thought Day fled to Europe to avoid being punished. But new evidence shows that Day stayed in England. He secretly set up a printing press near William Cecil's property in Lincolnshire. There, he continued to print Protestant books that went against the government. These books included writings by Lady Jane Grey, John Hooper, and Stephen Gardiner. They also attacked Queen Mary and her advisors.

On October 16, 1554, Day was caught and sent to the Tower of London. He was imprisoned for printing "naughty books," meaning forbidden ones. In the Book of Martyrs, John Foxe wrote about Day being in prison for his religious beliefs. Day was released the next year. This might have been because there weren't enough printers due to many foreign Protestant workers leaving England. He was allowed to work again, but only for small printing jobs. He even worked with Seres (who was also just released from prison) to print Catholic books for a Catholic printer, John Wayland. This was very different from the Protestant books he printed before. He also served as the official printer for the City of London for two years.

A New Era: Elizabethan Period

When Queen Mary died and Elizabeth I became queen in 1558, Day's business thrived again. Day was already close to Cecil, who was now one of the new Queen's main advisors. Through Cecil, Day received a valuable special right to print ABCs. He also became friends with Robert Dudley, another of Elizabeth's favorites.

With the help of his powerful friends, Day got a profitable patent to print William Cuningham's Cosmographical Glasse. He printed the first edition in 1559. He used a new, high-quality italic font and many impressive woodcuts. Day paid for the high production costs himself. He knew the book would make him famous as a master printer. This patent gave him the exclusive right to print Cuningham's work for life. It also gave him a seven-year monopoly on other new works. These works had to be paid for by Day and not go against the Bible or the law. This rule would bring him a lot of money for the rest of his life.

Day used this monopoly rule to his advantage. He brought back his earlier patent for The ABC with Little Catechism. In 1559, he got a patent for The Whole Booke of Psalmes, Collected into English Meter. This was a book of psalms set to music. Day first published it in 1562. The Stationers' Company gave Day the right to print all "psalmes in metre with note." Even though psalms were often learned by heart, this business was very profitable. It showed that more people were learning to read music. The Whole Booke of Psalmes became the best-selling book of its time. It was the standard English psalm book. Day's special rights to these popular books made him very wealthy. They also caused many arguments between him and other printers. Later, it was estimated that these patents were worth between £200 and £500 each year.

A Big Project: The Book of Martyrs

In 1563, Day started the work he is most famous for: John Foxe's Actes and Monuments. This book is also known as The Book of Martyrs. Day and Foxe likely met through Cecil. They became very close partners. Foxe believed that printing was a great way to spread the Protestant Reformation. Some say Foxe actually lived at Day's shop while the book was being made. Foxe was always revising and adding new material.

Day put a lot of time and money into making Foxe's book. It was the biggest publishing project ever done in England at that time. Day was very involved in putting the material together. He used different type sizes and fonts to show what was Foxe's own writing and what came from other sources. The finished folio was large and filled with woodcuts. It was an expensive luxury item, but it sold well. Day made a good profit from his investment.

Woodcut from Day's 1563 first printing of John Foxe's Actes and Monuments showing the execution of Thomas Cranmer, 1556

|

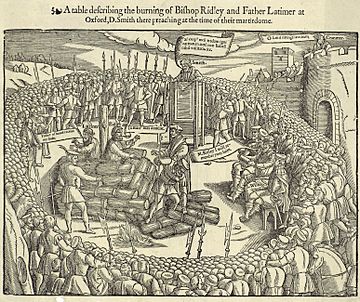

Woodcut from John Foxe's Actes and Monuments showing the burning of Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley in 1555

|

Day continued to take on difficult projects. He had already printed the first English book of church music in 1560. In 1567, Matthew Parker, the Archbishop of Canterbury, asked Day to print a collection of writings. These writings were from the tenth-century Aelfric of Eynsham. For this book, Day, known for his many fine fonts, had the first-ever Anglo-Saxon type made. Parker paid for this special font. The font might have been designed by François Guyot, a French type-founder who worked for Day. Day used the same font to print Lambarde's Archaionomia in 1568. This book was a collection of Anglo-Saxon laws.

In 1570, he printed Billingsley and Dee's English Euclid. This book included diagrams that could be folded and moved. It was one of the first printed books ever to do this. In the same year, he printed Ascham's Scholemaster.

Day and Foxe finished a second edition of the Book of Martyrs in 1570. It was even bigger than the first. It had 2,300 pages in two huge volumes. At one point, Day ran out of paper, which he imported. He had to paste smaller sheets together to finish the book. This edition received official recognition. William Cecil and the Privy Council told churches to make sure copies were available. In 1571, the Convocation ordered that every cathedral church and senior clergy member should own a copy. This edition cost sixteen shillings, which was about two months' wages for a skilled London clothworker at the time.

Later Years and His Impact

By the late 1570s, some less wealthy members of the Stationers' Company were unhappy about Day's many patents. He had to go to court against printers who illegally copied books he had the rights to. One printer, Roger Ward, admitted to copying 10,000 copies of ABC with Catechisms. He even used a font that looked like Day's. John Wolfe, Day's former apprentice, admitted to copying The Whole Booke of Psalmes. But he said Day's monopolies were unfair and stopped others from trading. Wolfe led a group of "poor printers" in a campaign against these patents. Because of an official investigation, Day had to give up some titles to the Company. This helped the poorer printers, but he kept the most profitable books.

In 1580, Day became the Master of the Stationers' Company. He worked hard to protect the printing industry from piracy. His official powers included the right to "search and seize" illegal materials. He used this power to help the trade and his own interests. In 1584, he sent men to break into Wolfe's shop. They destroyed any materials related to suspected piracy. Four years earlier, he had even destroyed his son Richard's printing equipment. Richard had printed the ABC and the Psalmes without his father's permission. Even though Richard was partly allowed to print these titles, John Day took him to court. This almost ended Richard's printing career.

In 1582, Day's health began to get worse. Even though he was weakening, he rushed to finish another edition of Actes and Monuments in 1583. He used at least four presses to print it. It was rare for books of this size to have more than one or two printings. Holinshed's Chronicles, a book similar to the Book of Martyrs in size and fame, never had a third edition.

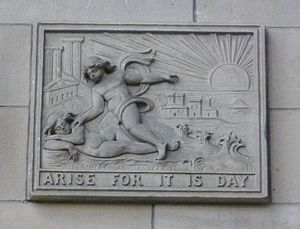

John Day died on July 23, 1584, in Walden, Essex. He was married twice and had twenty-four children. His oldest sons from his first marriage were Richard (born December 21, 1552) and Edward. His oldest sons from his second wife, Alice, were John (who was religious) and Lionel (who loved to study). Day's printer's symbol showed a sleeping person waking up. His motto was "Arise for it is Day." This was a play on his name and a reference to the new era of religious reform, in which he played a very important part.

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |