Edward VI facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Edward VI |

|

|---|---|

Portrait by William Scrots, c. 1550

|

|

| King of England and Ireland (more ...) | |

| Reign | 28 January 1547 – 6 July 1553 |

| Coronation | 20 February 1547 |

| Predecessor | Henry VIII |

| Successor | Jane (disputed) or Mary I |

| Regents |

See list

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (1547–1549)

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1549–1553) |

| Born | 12 October 1537 Hampton Court Palace, Middlesex, England |

| Died | 6 July 1553 (aged 15) Greenwich Palace, England |

| Burial | 8 August 1553 Westminster Abbey |

| House | Tudor |

| Father | Henry VIII of England |

| Mother | Jane Seymour |

| Religion | Anglican |

| Signature |  |

Edward VI (born 12 October 1537 – died 6 July 1553) was the King of England and Ireland. He ruled from 1547 until his death in 1553. Edward was crowned king on 20 February 1547 when he was just nine years old.

He was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour. Edward was also the first English king to be raised as a Protestant. Because he was so young, England was ruled by a group of advisors called a regency council. This council was first led by his uncle, Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (from 1547 to 1549). Later, it was led by John Dudley, 1st Earl of Warwick (from 1550 to 1553).

Edward's time as king saw some tough economic times and social problems. In 1549, these problems led to riots and rebellions. There was also an expensive war with Scotland. Even though it started well, England eventually pulled its troops out of Scotland and Boulogne-sur-Mer to make peace.

During Edward's reign, the Church of England became clearly Protestant. Edward was very interested in religious matters. His father, Henry VIII, had separated the Church from Rome. However, Henry still kept many Catholic traditions. Under Edward, Protestantism became the official religion in England. Reforms included stopping priests from marrying and getting rid of the Mass. Church services also had to be held in English.

In February 1553, when he was 15, Edward became very sick. When it became clear he would not recover, he and his council made a plan for who would become king or queen next. This plan was called the "Devise for the Succession." Edward wanted to stop England from returning to Catholicism. He named his cousin, Lady Jane Grey, as his heir. He left out his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth.

After Edward died, his decision was challenged. Jane was queen for only nine days before Mary took the throne. Mary was Catholic and changed Edward's Protestant reforms. However, Elizabeth later brought them back in 1559.

Contents

Edward's Early Life

When Was Edward Born?

Edward was born on 12 October 1537 at Hampton Court Palace in Middlesex. He was the son of King Henry VIII and his third wife, Jane Seymour. People across England were very happy and relieved to have a male heir. They had waited "so long" for a prince. Churches sang special hymns, bonfires were lit, and over two thousand cannons were fired at the Tower of London.

Queen Jane seemed to recover quickly after giving birth. She sent out letters announcing the birth of "a Prince, conceived in most lawful matrimony." Edward was baptized on 15 October. His half-sister, 21-year-old Lady Mary, was his godmother. Four-year-old Lady Elizabeth carried his baptismal cloth. He was then declared Duke of Cornwall and Earl of Chester.

However, the queen became ill on 23 October and died the next night. It is thought she had problems after childbirth. Henry VIII wrote to the King of France that his joy was mixed with the sadness of his wife's death.

How Was Edward Raised and Educated?

Edward was a healthy baby. His father, Henry VIII, was very happy with him. In 1538, Henry was seen "dallying with him in his arms" and showing him to the people. Later that year, Lord Audley said Edward was growing fast and was strong. Other reports describe him as a tall and cheerful child. Some historians used to think Edward was often sick, but newer studies say he was generally healthy. He had a serious fever at age four, but he was mostly well until the last six months of his life.

Edward was first cared for by Margaret Bryan. Later, Blanche Herbert, Lady Troy took over. Until he was six, Edward was raised "among the women," as he later wrote. His royal household was first led by Sir William Sidney, then by Sir Richard Page. Henry VIII demanded very high standards of safety and cleanliness for his son. He called Edward "this whole realm's most precious jewel." Visitors said the prince was a happy child, with many toys and comforts, including his own group of musicians.

From age six, Edward began his formal education. His main teachers were Richard Cox and John Cheke. He studied "tongues, of the scripture, of philosophy, and all liberal sciences." He also learned from his sister Elizabeth's tutor, Roger Ascham, and from Jean Belmain. Edward learned French, Spanish, and Italian. He also studied geometry and played musical instruments like the lute and the virginals. He collected globes and maps. Historians believe he was very intelligent, especially about money matters.

Edward's religious education focused on Protestant ideas. His religious teachers were likely chosen by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, a leading reformer. Both Cox and Cheke were "reformed" Catholics or followers of Erasmus. By 1549, Edward had written about the pope as the Antichrist. He also took notes on religious debates. In his early years, Edward followed some Catholic practices, like attending Mass. However, he became convinced that "true" religion should be established in England.

Both of Edward's sisters visited him often. Elizabeth once gave him a shirt she had made herself. Edward enjoyed Mary's company, even though he did not like her foreign dances. In 1546, he wrote to her, "I love you most." In 1543, Henry VIII invited his children to spend Christmas with him. This showed that he had made up with his daughters, whom he had previously disinherited. The next spring, he put them back in line for the throne. He also set up a regency council for when Edward was a child. This family peace was likely due to Henry's new wife, Catherine Parr. Edward grew very fond of her. He called her his "most dear mother."

Other children played with Edward. One girl later remembered him as "a marvellous sweet child, of very mild and generous condition." Edward was educated with sons of nobles. One of them, Barnaby Fitzpatrick, became a close friend. Edward was more dedicated to his schoolwork than his classmates. He seemed to do better than them, wanting to do his "duty" and compete with Elizabeth's academic skills.

Edward's rooms were decorated with expensive tapestries. His clothes, books, and cutlery were covered in jewels and gold. Like his father, Edward loved military arts. Many portraits show him with a gold dagger, just like Henry. Edward's own writings excitedly describe English military campaigns.

The "Rough Wooing" War

On 1 July 1543, Henry VIII signed a peace treaty with Scotland. This treaty included Edward's betrothal to the seven-month-old Mary, Queen of Scots. Scotland was weak after a defeat in 1542. Henry wanted to unite the two kingdoms. He demanded that Mary be sent to England to be raised there.

However, the Scots rejected the treaty in December 1543. They renewed their alliance with France. Henry was furious. In April 1544, he ordered Edward's uncle, Edward Seymour, to invade Scotland. He told Seymour to "put all to fire and sword, burn Edinburgh town... as there may remain forever a perpetual memory of the vengeance of God." Seymour carried out a very harsh campaign against the Scots. This war, which continued into Edward's reign, is known as "the Rough Wooing."

Becoming King

On 10 January 1547, the nine-year-old Edward wrote to his father and stepmother. He thanked them for their portraits, which were New Year's gifts. By 28 January, Henry VIII had died. Those close to the throne, like Edward Seymour and William Paget, decided to keep the king's death a secret for a few days. They wanted to make sure the change of power went smoothly.

Seymour and Sir Anthony Browne rode to get Edward from Hertford. They brought him to Enfield, where Lady Elizabeth was living. There, Edward and Elizabeth were told about their father's death. They also heard his will read aloud.

On 31 January, Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley announced Henry's death to Parliament. Orders were given to announce Edward's new rule everywhere. The new king was taken to the Tower of London. He was greeted with "great shot of ordnance" from the Tower and ships. The next day, the nobles of the kingdom swore loyalty to Edward at the Tower. Seymour was then announced as Protector. Henry VIII was buried at Windsor on 16 February, next to Jane Seymour, as he had wished.

Edward VI was crowned at Westminster Abbey on Sunday, 20 February. The ceremony was made shorter. This was because it was "tedious" and might "weary and be hurtsome" to the young king. Also, the Reformation meant some parts of the old ceremony were no longer suitable.

The day before his coronation, Edward rode from the Tower to the Palace of Westminster. Crowds cheered him, and there were many parades. He laughed at a Spanish tightrope walker who performed outside St Paul's Cathedral.

At the coronation service, Archbishop Cranmer spoke about the king's power over the Church. He called Edward a new Josiah, a biblical king who destroyed idols. Cranmer urged Edward to continue reforming the Church of England. He said to banish "the tyranny of the Bishops of Rome" and remove images. After the service, Edward had a feast in Westminster Hall. He remembered dining with his crown on his head.

Somerset's Rule as Protector

The Council of Regency

Henry VIII's will named sixteen people to act as Edward's council until he turned eighteen. These people were helped by twelve other advisors. There has been some debate about Henry VIII's will. Some historians think that people close to the king changed the will. They wanted to gain power and wealth for themselves. This meant that by late 1546, the king's inner circle had more Protestant supporters.

Also, two important conservative advisors were removed from power. Stephen Gardiner was not allowed to see Henry in his last months. Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, was accused of treason. His lands were taken, making them available for others. He stayed in the Tower of London for all of Edward's reign. Other historians argue that Gardiner was excluded for other reasons. They also say Norfolk was not very conservative in religion.

After Henry's death, many lands and titles were given to the new powerful group. The will had a special clause that allowed the advisors to give out lands and honors. This especially benefited Edward Seymour, the king's uncle. He became Lord Protector of the Realm, in charge of the king and the country. He was also made Duke of Somerset.

Henry VIII's will did not actually say there should be a Protector. It said the country should be ruled by a council working together. But a few days after Henry's death, on 4 February, the advisors chose Somerset as Protector. Thirteen of the sixteen advisors agreed. They said it was their joint decision based on Henry's will. Somerset might have made deals with some advisors, who almost all received gifts.

Somerset becoming Protector was similar to what had happened before in history. His military successes in Scotland and France also made him seem suitable. In March 1547, King Edward gave him special permission. This allowed Somerset to choose members for the Privy Council himself and only ask for their advice when he wanted. He ruled mostly by issuing official orders. He rarely asked the Privy Council for more than their approval.

Somerset took power smoothly. The ambassador from the Holy Roman Empire said Somerset "governs everything absolutely." He predicted trouble from John Dudley, who had recently become Earl of Warwick. In the first few weeks, Somerset was only challenged by the Chancellor, Thomas Wriothesley. Wriothesley was a religious conservative. He did not like Somerset taking so much power over the council. Wriothesley was then removed from his position.

Thomas Seymour's Actions

Somerset faced problems from his younger brother, Thomas. Thomas Seymour was described as a "worm in the bud." As King Edward's uncle, Thomas wanted to be in charge of the king's person. He also wanted more power. Somerset tried to keep him happy by making him a baron and Lord Admiral. He also gave him a seat on the Privy Council. But Thomas kept plotting for power.

He secretly gave King Edward pocket money. He told Edward that Somerset was too strict with money, making him a "beggarly king." He also urged the king to get rid of the Protector within two years. But Edward had been taught to respect the council and did not cooperate. In spring 1547, Thomas Seymour secretly married Henry VIII's widow, Catherine Parr. Her household included 11-year-old Lady Jane Grey and 13-year-old Lady Elizabeth.

In summer 1548, Catherine Parr discovered Thomas Seymour acting improperly with Lady Elizabeth. Elizabeth was then moved out of Parr's household. In September, Parr died after childbirth. Seymour quickly tried to get Elizabeth's attention again, planning to marry her. Elizabeth was interested, but like Edward, she would not agree to anything without the council's permission.

In January 1549, the council arrested Thomas Seymour. He was accused of various crimes, including stealing money from the Bristol mint. King Edward himself spoke about the pocket money Seymour had given him. There was not enough clear proof for a trial for treason. So, Seymour was condemned by a special act of Parliament and executed on 20 March 1549.

War with Scotland and France

Somerset was skilled as a soldier. He had shown this in Scotland and in defending Boulogne-sur-Mer in 1546. As Protector, his main focus was the war against Scotland. After a big victory at the Battle of Pinkie in September 1547, he set up many military bases in Scotland.

However, his initial successes did not last. His goal of uniting the kingdoms through conquest became difficult. The Scots allied with France, who sent help to defend Edinburgh in 1548. The Queen of Scots was moved to France and engaged to the French prince. The cost of Somerset's large armies and bases in Scotland was too much for the royal treasury. A French attack on Boulogne in August 1549 finally forced Somerset to start pulling troops out of Scotland.

Rebellions and Somerset's Downfall

In 1548, there was social unrest in England. After April 1549, many armed revolts broke out. These were caused by religious issues and problems with farming land. The two most serious rebellions were in Devon and Cornwall, and in Norfolk. The first, called the Prayer Book Rebellion, was against the new Protestant religion. The second, Kett's Rebellion, was led by Robert Kett. It was mainly about landlords taking over common grazing land.

A complicated part of these problems was that the rebels thought they were acting correctly. They believed they were fighting against landlords who were breaking the law, and that the Protector supported them. This idea came partly from Somerset's confusing orders. It also came from the investigations he sent out in 1548 and 1549. These investigations looked into complaints about lost farmland and landlords taking over common land.

Whatever people thought of Somerset, the terrible events of 1549 showed a huge failure in government. The council blamed the Protector. In July 1549, Paget wrote to Somerset, saying that everyone on the council disliked his actions.

The events that led to Somerset being removed from power are often called a coup d'état (a sudden takeover of power). By 1 October 1549, Somerset knew his rule was in danger. He asked for help, took control of the king, and went to the strong Windsor Castle for safety. Edward wrote that he felt "in prison." Meanwhile, the united council published details of Somerset's poor management. They made it clear that Somerset's power came from them, not from Henry VIII's will.

On 11 October, the council arrested Somerset. They brought the king to Richmond Palace. Edward wrote in his Chronicle about the charges against Somerset. These included "ambition, vainglory, entering into rash wars... enriching himself of my treasure, following his own opinion, and doing all by his own authority." In February 1550, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, became the leader of the council. He was Somerset's replacement.

Somerset was released from the Tower and returned to the council. However, he was executed in January 1552 after trying to overthrow Dudley's government. Edward noted his uncle's death in his Chronicle: "the duke of Somerset had his head cut off upon Tower Hill."

Historians compare Somerset's efficient takeover of power with his later poor rule. By autumn 1549, his expensive wars had stalled. The country faced financial ruin, and rebellions had broken out. For a long time, historians thought highly of Somerset. This was because he seemed to support common people against greedy landowners. However, more recently, he has been seen as an arrogant ruler who lacked political and management skills.

Northumberland Takes Charge

In contrast to Somerset, his successor, the Earl of Warwick (who became Duke of Northumberland in 1551), was once seen as a greedy plotter. People thought he only cared about getting rich at the country's expense. But since the 1970s, historians have recognized his achievements in government and the economy. He is now credited with bringing back the royal council's authority. He also helped the government recover after Somerset's difficult time.

The Earl of Warwick's rival for leadership was Thomas Wriothesley. Wriothesley's conservative supporters had joined with Warwick's followers. They formed a united council. People expected this council to reverse Somerset's religious reforms. Warwick, however, relied on the king's strong Protestant beliefs. He claimed Edward was old enough to rule himself. Warwick moved himself and his people closer to the king, taking control of the Privy Chamber.

Warwick made sure he always had a majority of advisors on his side. He encouraged the council to work together and used it to make his power seem legitimate. Since he was not related to the king by blood, he added members from his own group to the council to control it. He also put his family members in the royal household. He knew that to be in charge, he needed to control how the council worked.

As Edward grew up, he understood more and more about government. However, how much he actually made decisions has been debated. When Edward was fourteen, a special "Counsel for the Estate" was created. He chose the members himself. In weekly meetings, Edward would "hear the debating of things of most importance." The king worked closely with William Cecil and William Petre, the main secretaries. The king's biggest influence was in religious matters. The council followed the strong Protestant policy that Edward wanted.

Northumberland's war policies were more practical than Somerset's. In 1550, he signed a peace treaty with France. This meant pulling troops out of Boulogne and all English bases in Scotland. In 1551, Edward was engaged to Elisabeth of Valois, the daughter of King Henry II. Warwick realized England could no longer afford expensive wars. At home, he worked to control local unrest. To prevent future rebellions, he kept royal representatives in local areas. These included lords lieutenant, who commanded military forces and reported to the central government.

Working with William Paulet and Walter Mildmay, Warwick dealt with the kingdom's terrible finances. However, his government first tried to make quick money by making coins with less precious metal. This caused economic disaster. Warwick then let the expert Thomas Gresham take charge. By 1552, people trusted the coins again, prices fell, and trade improved. Although the economy did not fully recover until Elizabeth's reign, it started under Northumberland's policies. His government also stopped widespread theft of government money. They also thoroughly reviewed how taxes were collected.

The English Reformation Under Edward

In religion, Northumberland's government continued Somerset's policy. They supported a stronger program of reform. Even though Edward VI's direct influence on government was limited, his strong Protestant beliefs made a reforming government necessary. The people who supported him were Protestants, and they stayed in power throughout his reign.

The person Edward trusted most was Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Cranmer introduced many religious reforms. These changes transformed the English church from one that was mostly Catholic (though it rejected the Pope) to one that was clearly Protestant. Church property that had been taken under Henry VIII continued to be seized under Edward. This included the closing of chantries (places where prayers were said for the dead). This brought a lot of money to the crown and to the new owners of the property. So, church reform was both a political and a religious policy under Edward VI. By the end of his reign, the church had lost much of its wealth.

Historians are not sure how truly Protestant Somerset and Northumberland were. However, there is less doubt about King Edward's strong religious feelings. He was said to read twelve chapters of the Bible every day and loved sermons. John Foxe called him a "godly imp." Edward was often shown as a new Josiah, a biblical king who destroyed idols. He could be strict in his anti-Catholic views. He once asked Catherine Parr to persuade Lady Mary "to attend no longer to foreign dances and merriments." However, Edward's biographer Jennifer Loach warns against fully believing the very pious image of Edward given by reformers. In his early life, Edward followed Catholic practices, including attending Mass. But he became convinced that "true" religion should be established in England.

The English Reformation faced pressure from two sides. There were traditionalists who wanted to keep old ways. And there were zealots who destroyed images and complained that reforms did not go far enough. Cranmer worked to write a standard prayer book in English. This book described all weekly and daily services and religious festivals. It was made compulsory by the first Act of Uniformity of 1549. The Book of Common Prayer of 1549 was meant to be a compromise. But traditionalists criticized it for getting rid of many old rituals. Some reformers complained it kept too many "popish" elements. Many senior Catholic church leaders, like Bishops Stephen Gardiner and Edmund Bonner, also opposed the prayer book. Both were imprisoned and lost their positions. In 1549, over 5,500 people died in the Prayer Book Rebellion in Devon and Cornwall.

Protestant ideas became official. These included justification by faith alone (being saved by faith) and communion for everyone, not just priests. The Ordinal of 1550 changed how priests were appointed. It allowed ministers to preach the gospel and give sacraments.

After 1551, the Reformation continued to advance. Edward approved and encouraged these changes. He began to have more personal influence as Supreme Head of the church. New changes were also a response to criticism from reformers like John Hooper and John Knox. Cranmer was also influenced by other foreign religious thinkers. The Reformation moved faster as more reformers became bishops. In 1551–52, Cranmer rewrote the Book of Common Prayer. He made it more clearly Protestant. He also prepared a statement of beliefs, the Forty-two Articles. This clarified the reformed religion, especially about the communion service. Cranmer's new prayer book, published in 1552, effectively ended the Mass. This book, supported by a second Act of Uniformity, "marked the arrival of the English Church at Protestantism." The prayer book of 1552 is still the basis for Church of England services today. However, Cranmer could not finish all these reforms. It became clear in spring 1553 that King Edward was dying.

The Succession Crisis

Edward's Plan for Who Would Rule Next

In February 1553, Edward VI became ill. By June, he was in a very serious condition. If the king died and his Catholic half-sister Mary became queen, the English Reformation would be in danger. Edward's council and officers had many reasons to fear this. Edward himself did not want Mary to be queen. He felt she was not legitimate and that a male heir should rule.

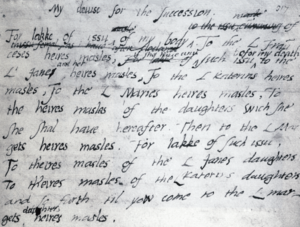

Edward wrote a document called "My devise for the succession." In it, he planned to change who would inherit the throne. He left out his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth. Instead, he chose his cousin, 16-year-old Lady Jane Grey. Jane had married Lord Guildford Dudley, a younger son of the Duke of Northumberland, on 25 May 1553.

In early June, Edward personally oversaw his lawyers writing a clean copy of his plan. He signed it in six places. On 15 June, he called high-ranking judges to his sickbed. He ordered them to prepare his plan as official letters patent. He also announced that he would have these approved by Parliament. Next, he had leading advisors and lawyers sign a document. In it, they agreed to follow Edward's will after his death.

Later, Chief Justice Edward Montagu remembered that when he and his colleagues raised legal concerns, Northumberland threatened them. He said he would "fight in his shirt with any man in that quarrel." Montagu also heard other lords say that if they refused, they would be "traitors." Finally, on 21 June, over a hundred important people signed the plan. These included advisors, nobles, archbishops, bishops, and sheriffs. Many later claimed they were forced to sign by Northumberland. However, Edward's biographer Jennifer Loach notes that "few of them gave any clear indication of reluctance at the time."

It was widely known that Edward was dying. Foreign diplomats suspected a plan to prevent Mary from becoming queen. France did not want the Holy Roman Emperor's cousin on the English throne. They secretly talked with Northumberland, showing support. The diplomats were sure that most English people supported Mary. But they still believed Queen Jane would successfully take the throne.

For centuries, people thought the attempt to change the succession was only Northumberland's plot. However, since the 1970s, many historians believe the king himself started the "devise" and insisted on it. Diarmaid MacCulloch suggests Edward had "teenage dreams of founding an evangelical realm of Christ." David Starkey says, "Edward had a couple of co-operators, but the driving will was his." Edward was convinced that his word was law. He fully supported disinheriting his half-sisters.

Edward's Illness and Death

Edward became ill in January 1553 with a fever and cough that slowly got worse. The ambassador from the Holy Roman Empire reported that Edward suffered a lot from breathing difficulties when he had a fever.

Edward felt well enough in early April to go outside at Westminster. He also moved to Greenwich. But by the end of the month, he was weaker again. By 7 May, he was "much amended," and his doctors were sure he would recover. A few days later, the king was watching ships on the Thames from his window. However, he got worse. On 11 June, the ambassador reported that Edward was coughing up greenish-yellow, black, or pink fluid, like blood. His doctors now believed he had a "suppurating tumour" (an infected growth) in his lung. They admitted Edward would not recover. Soon, his legs swelled so much that he had to lie on his back. He lost the strength to fight the disease. He whispered to his tutor, John Cheke, "I am glad to die."

Edward made his last public appearance on 1 July. He showed himself at his window in Greenwich Palace. Those who saw him were shocked by how "thin and wasted" he looked. Over the next two days, large crowds came hoping to see the king again. But on 3 July, they were told the weather was too cold for him to appear. Edward died at age 15 at Greenwich Palace at 8 p.m. on 6 July 1553. According to a famous account, his last words were: "I am faint; Lord have mercy upon me, and take my spirit."

Edward was buried in the Henry VII Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey on 8 August 1553. The service followed Protestant rites and was led by Thomas Cranmer. The procession was led by "a grett company of chylderyn in ther surples" (a large group of children in their white robes). Londoners watched, "wepyng and lamenting" (crying and mourning). The funeral carriage was covered in gold cloth. On top was a statue of Edward, with his crown, sceptre, and garter. Edward's burial place was not marked until 1966. Then, Christ's Hospital school placed a stone in the chapel floor to honor its founder.

The exact cause of Edward VI's death is not certain. Like many royal deaths in the 16th century, there were rumors of poisoning. But no proof has ever been found. The Duke of Northumberland was very unpopular after Edward's death. Many believed he had ordered the poisoning. Another idea was that Catholics had poisoned Edward to bring Mary to the throne. The surgeon who examined Edward after his death found that "the disease whereof his majesty died was the disease of the lungs." The Venetian ambassador reported that Edward died of consumption, which means tuberculosis. Many historians accept this diagnosis. Some believe Edward got tuberculosis after having measles and smallpox in 1552. Others suggest his symptoms were typical of severe bronchopneumonia, leading to a lung infection, blood poisoning, and kidney failure.

Lady Jane Grey and Queen Mary

Lady Mary last saw Edward in February. She was kept informed about his health by Northumberland and her contacts with foreign ambassadors. Knowing Edward was about to die, she left Hunsdon House and went to her estates in Norfolk. There, she knew her tenants would support her. Northumberland sent ships to the Norfolk coast to stop her from escaping or getting help from other countries. He delayed announcing the king's death while he gathered his forces. Jane Grey was taken to the Tower on 10 July. On the same day, she was proclaimed queen in London, but people were unhappy.

The Privy Council received a message from Mary. She claimed her "right and title" to the throne and ordered the council to proclaim her queen. The council replied that Jane was queen by Edward's authority. They said Mary was illegitimate and only supported by "a few base people."

Northumberland soon realized he had made a huge mistake. He had failed to capture Mary before Edward's death. Many who supported Mary were Catholics hoping to restore their religion. But her supporters also included many who believed her claim to the throne was lawful, regardless of religion. Northumberland had to give up control of the nervous council in London. He then had to chase Mary into East Anglia. News was arriving that her support was growing. She had nobles, gentlemen, and "innumerable companies of the common people" on her side. On 14 July, Northumberland marched out of London with three thousand men. Mary gathered an army of nearly twenty thousand by 19 July.

The Privy Council then realized they had made a terrible mistake. Led by the Earls of Arundel and Pembroke, the council publicly proclaimed Mary as queen on 19 July. Jane's nine-day reign ended. This announcement caused huge celebrations throughout London.

Edward's Protestant Legacy

Even though Edward ruled for only six years and died at 15, his reign had a lasting impact on the English Reformation and the Church of England. The last ten years of Henry VIII's reign had seen the Reformation slow down. It had even started to return to some Catholic ways. In contrast, Edward's reign saw big changes in the Reformation. The Church changed from having mostly Catholic services and structure to being clearly Protestant.

Specifically, the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer, the Ordinal of 1550, and Cranmer's Forty-two Articles formed the basis for English Church practices that continue today. Edward himself fully approved these changes. While reformers like Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer, and Nicholas Ridley did the work, the fact that the king was Protestant helped speed up the Reformation during his reign.

Queen Mary tried to undo her brother's reforms, but she faced major challenges. Even though she believed in the Pope's power, she ruled as the Supreme Head of the English Church. This was a contradiction that bothered her. She found she could not get back the many church properties that had been given or sold to private landowners. Although she executed some leading Protestant churchmen, many reformers either left England or continued their activities secretly. They produced a lot of Protestant writings that she could not stop.

However, Protestantism was not yet deeply rooted in the English people. If Mary had lived longer, her Catholic changes might have succeeded. In that case, Edward's reign, rather than hers, might have been seen as a historical mistake.

When Mary died in 1558, the English Reformation continued. Most of the reforms from Edward's reign were brought back in the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. Queen Elizabeth replaced Mary's advisors and bishops with people who had served Edward. These included William Cecil, Northumberland's former secretary, and Richard Cox, Edward's old tutor. Cox preached an anti-Catholic sermon when Parliament opened in 1559. Parliament passed an Act of Uniformity the next spring. This act restored Cranmer's prayer book of 1552, with some changes. The Thirty-nine Articles of 1563 were largely based on Cranmer's Forty-two Articles. The religious ideas developed during Edward's reign were very important for Elizabeth's religious policies.

Family tree

| Family of Edward VI | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

In Spanish: Eduardo VI de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Eduardo VI de Inglaterra para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |