Thirty-nine Articles facts for kids

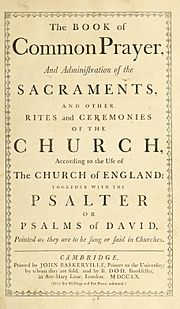

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion are important statements about what the Church of England believes and how it practices its faith. They were finalized in 1571 and helped to settle many arguments during the English Reformation. These Articles are found in the Book of Common Prayer, which is used by the Church of England and other churches around the world that are part of the Anglican Communion.

The story of these Articles began when Henry VIII decided to separate the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church. He was even kicked out of the Catholic Church for this! Henry wanted the English monarch (himself) to be the head of the Church, not the Pope. He then needed to decide what the new English Church would believe, especially compared to the Roman Catholic Church and the new Protestant groups in Europe. Over about 30 years, several documents were written and changed as the situation in England kept shifting. This started with the Ten Articles in 1536 and ended with the Thirty-nine Articles in 1571. These final Articles helped to define the Church of England's beliefs, especially in relation to Calvinist ideas and Roman Catholic practices.

Before the final Thirty-nine Articles, there were at least five main versions. The first was the Ten Articles in 1536, which showed some leanings towards Protestant ideas, partly because England wanted to be friends with German Lutheran leaders. Next came the Six Articles in 1539, which moved back towards more traditional Catholic views. Then, the King's Book in 1543 brought back most of the older Roman Catholic beliefs. When Henry VIII's son, Edward VI, became king, the Forty-two Articles were written in 1552 by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. These articles showed the strongest influence of Calvinist ideas in the English Church. However, they were never put into practice because Edward VI died, and his older sister, Mary I, brought the English Church back to Roman Catholicism.

Finally, when Elizabeth I became Queen, she brought the Church of England back to being separate from the Roman Catholic Church. The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion were started by a meeting of church leaders in 1563, led by Matthew Parker, who was the Archbishop of Canterbury. The Articles were finished in 1571 and added to the Book of Common Prayer. Even though there were still disagreements between Catholic and Protestant people, this book helped to make the English language more standard and had a big impact on religion in the United Kingdom and other places.

Contents

Early Versions of the Articles

Ten Articles (1536): First Steps for the Church

When the Church of England separated from Rome, there was a lot of confusion about what to believe. Some church leaders wanted to keep things mostly Catholic but without the Pope, while others wanted to be more Protestant. To bring "peace and unity," the Ten Articles were created in July 1536. These were the first official statements of belief for the English Church after it left the Pope's authority. The Ten Articles were a quick compromise between different groups. Some historians see them as a win for Lutheran ideas, while others see them as a success for Catholic traditions. They were also described as a bit "confusing."

The first five articles talked about beliefs that were "commanded by God and necessary for our salvation." The last five articles were about "good ceremonies used in the Church." This split happened because the Articles came from two different discussions earlier that year. The first five articles were based on talks between English representatives and German Lutheran thinkers like Martin Luther. These ideas were also based on the Augsburg Confession from 1530.

The main beliefs in the first five articles were about the Bible, baptism, penance (confession), the Eucharist (Communion), and justification (being made right with God). A key idea in the Ten Articles was that people are made right with God through faith. This means that God forgives sins and accepts people because of Jesus Christ and his sacrifice. Good actions would come after, not before, being made right with God. However, the Lutheran influence was softened. Justification was achieved "by contrition (being sorry for sins) and faith joined with love." So, good actions were still "needed to reach everlasting life."

To the disappointment of traditionalists, only three of the usual seven sacraments were mentioned: baptism, the Eucharist, and penance. The Articles confirmed that Christ is truly present in the Eucharist, saying that "under the form of bread and wine... is truly, really contained the very body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ." This was okay for those who believed in transubstantiation (the bread and wine becoming Christ's body and blood) or sacramental union (Christ being present with the bread and wine). But it clearly went against ideas that denied Christ's real presence. More surprisingly for reformers, the Articles kept penance as a sacrament and said that a priest could truly forgive sins in confession.

Articles six to ten focused on less important issues. Interestingly, purgatory, which was a big part of medieval religion, was put in the non-essential articles. The Ten Articles were unclear about whether purgatory existed, saying that "the place where [departed souls] are, its name, and the kind of pains there" were "uncertain by scripture." Prayer for the dead and masses for the dead were allowed, as they might help souls in purgatory.

The Articles also supported some Catholic rituals that Protestants didn't like, such as kissing the cross on Good Friday. But they also mildly criticized common abuses. Using religious images was allowed, but people were taught not to kneel or make offerings to them. Praying to Mary, mother of Jesus, and other saints was allowed, as long as it wasn't superstition.

In short, the Ten Articles stated:

- 1. The Bible and the three main ecumenical creeds are the foundation of Christian faith.

- 2. Baptism forgives sins and gives new life, and it's needed for salvation, even for babies. It spoke against the ideas of Anabaptists.

- 3. The sacrament of penance, with confession and forgiveness, is needed for salvation.

- 4. That the body and blood of Christ are truly present in the Eucharist.

- 5. Justification (being made right with God) is by faith, but good actions are also necessary.

- 6. Images can be used to show good examples and remind people of sins, but not to be worshipped.

- 7. Saints should be honored as examples and as helpers in prayer.

- 8. Praying to saints is allowed, and holy days should be observed.

- 9. Many church rituals, like clerical vestments and holy water, are good, but they don't forgive sin.

- 10. Praying for the dead is good, but the idea of purgatory is not clear in the Bible. Abuses related to purgatory, like claims that papal indulgences could immediately free souls, were rejected.

Bishops' Book (1537): More Instructions for Christians

Because the Ten Articles didn't stop all the arguments, Thomas Cromwell, a key advisor to the King, called a meeting of bishops and church leaders in February 1537. This meeting created a book called The Institution of the Christian Man, often called The Bishops' Book. The word "institution" here means "instruction." This book kept the slightly Protestant ideas of the Ten Articles. The sections on justification, purgatory, and the sacraments of baptism, the Eucharist, and penance were included without changes.

When the meeting happened, traditionalists were still upset that four of the usual seven sacraments (confirmation, marriage, holy orders, and extreme unction) were left out of the Ten Articles. John Stokesley argued for all seven, while Thomas Cranmer only recognized baptism and the Eucharist. The others were divided. The traditionalists had a hard time because they had to rely on old church traditions, which went against Cromwell's rule that all arguments must come from the Bible.

In the end, the missing sacraments were brought back but put in a separate section to show they were "different in importance and necessity." Only baptism, the Eucharist, and penance were "started by Christ, to be certain tools or remedies necessary for our salvation." Confirmation was said to have been started by the early Church based on what they read about the Apostles' practices.

The Bishops' Book also explained the creed, the Ten Commandments, the Lord's Prayer, and the Hail Mary. These parts were heavily influenced by a prayer book from 1535, which itself was influenced by Luther's writings. Following this, The Bishops' Book changed the traditional Catholic way of numbering the Ten Commandments. It separated the rule against making and worshipping graven images from the first commandment ("Thou shalt have no other gods before me"). This was similar to the Jewish tradition and the Eastern Orthodox Church. While allowing images of Christ and saints, the book taught against pictures of God the Father. It also criticized those who "are more ready to decorate dead images beautifully, than to use the same to help poor Christian people, the living images of God." Such teachings encouraged iconoclasm (destroying religious images), which became a part of the English Reformation.

The Bishops' Book was given to the King in August 1537. He ordered parts of it to be read in churches every Sunday. However, the King wasn't completely happy and started to make his own changes, which made the book less focused on justification by faith. This changed version was never published. Because the Bishops' Book was never officially approved by the King or the church leaders, the Ten Articles remained the official beliefs of the Church of England.

Six Articles (1539): A Step Backwards for Reformers

King Henry VIII was worried about being alone diplomatically and facing a Catholic alliance. So, he kept trying to make friends with the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League in Germany. In May 1538, three Lutheran thinkers came to London and met with English bishops and clergy.

The Germans offered a list of beliefs based on the Lutheran Confession of Augsburg as a way to agree. But bishops like Cuthbert Tunstall and John Stokesley were not convinced by these Protestant ideas. They tried hard to avoid agreement. They were willing to separate from Rome, but they wanted to join with the Greek Orthodox Church, not with the Protestants in Europe. The bishops also refused to get rid of practices that the Germans considered wrong, such as private masses for the dead, forced clerical celibacy (priests not marrying), and not giving communion wine to regular church members. Stokesley thought these customs were important because the Greek Church practiced them. Since the King didn't want to change these practices, all the Germans left England by October 1.

Meanwhile, England was in religious chaos. Impatient Protestants started making more changes themselves. Some priests said mass in English instead of Latin and got married without permission (Archbishop Cranmer himself was secretly married). Protestants were also divided. Some, like Lutherans, believed Christ was truly present in the Eucharist. Others, like Anabaptists, denied this. In May 1539, a new Parliament met, and Lord Chancellor Audley said the King wanted everyone to have the same religious beliefs. A group of eight bishops (four traditional and four reform-minded) was chosen to look at and decide on beliefs. On May 16, the Duke of Norfolk noted that the group couldn't agree on anything. He suggested that Parliament look at six difficult questions that became the basis of the Six Articles:

- 1. Could the Eucharist be the true body of Christ without transubstantiation (the bread and wine literally becoming Christ's body and blood)?

- 2. Did regular church members need to receive Communion in both bread and wine?

- 3. Did vows of chastity (not marrying) have to be kept as a divine law?

- 4. Should priests be forced to remain unmarried?

- 5. Were private masses (masses for specific intentions) required by divine law?

- 6. Was confession to a priest necessary as a divine law?

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act for abolishing of Diversity of Opinions of certain Articles concerning Christian Religion. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 25 Hen. 8. c. 14 |

Quick facts for kids Other legislation |

|

| Repealed by | Treason Act 1547 |

|

Status: Repealed

|

|

For the next month, these questions were debated in Parliament and among church leaders, with the King actively involved. The final result was an agreement on traditional teachings for all but the sixth question. Communion in one kind (bread only), forced celibacy for priests, vows of chastity, and private masses were all considered legitimate. Protestants got a small win on confession to a priest, which was declared "useful and necessary to keep" but not required by divine law. Also, while Christ's real presence was confirmed, the word transubstantiation itself was not used in the final version.

The Act of Six Articles became law in June 1539. Unlike the Ten Articles, this law had legal power. There were harsh punishments for breaking these Articles. Denying transubstantiation meant being burned to death without a chance to change your mind. Denying any of the other articles meant hanging or life imprisonment. Married priests had until July 12 to send their wives away, which was probably a concession to give Archbishop Cranmer time to move his wife and children out of England. After this law passed, bishops Latimer and Shaxton, who spoke out against it, had to leave their church positions. The Act of Six Articles was later cancelled by the Treason Act 1547 during the reign of Henry's son, Edward VI.

King's Book (1543): Henry VIII's Own Beliefs

When Parliament met again in April 1540, a group was formed to revise the Bishops' Book, which Henry VIII had never liked. This group included both traditionalists and reformers, but the traditionalists were the majority. Church leaders began discussing the revised text in April 1543. The King's Book, officially called The Necessary Doctrine and Erudition for Any Christian Man, was more traditional than the 1537 version and included many of the King's own changes. It was approved by a special meeting of nobles on May 6 and was different from the Bishop's Book because it was issued under the King's direct authority. It was also enforced by law through the Act for the Advancement of True Religion. Because it had royal approval, the King's Book officially replaced the Ten Articles as the Church of England's official statement of belief.

Importantly, the idea of justification by faith alone was completely rejected. Cranmer tried to save this idea by arguing that while true faith comes with good actions, it is only faith that makes a person right with God. However, Henry was not convinced, and the text was changed to say that faith justified "neither only nor alone." It also stated that each person had free will to be "a worker... in reaching his own justification." The King's Book also supported traditional views of the mass, transubstantiation, confession, and church ceremonies. All seven traditional sacraments were included without any difference in importance between them. It taught that the second commandment did not forbid images but only giving them "godly honor." Looking at images of Christ and the saints "provoked, kindled and stirred to yield thanks to Our Lord."

One area where the King's Book moved away from traditional teaching was on prayer for the dead and purgatory. It taught that no one could know if prayers or masses for the dead helped an individual soul. It was better to pray for "the whole group of Christian people, living and dead." People were encouraged to "avoid the name of purgatory, and no more argue or discuss it." This dislike for purgatory likely came from its connection to the Pope's authority. The King's own actions sent mixed signals. In 1540, he allowed money left for the souls of dead Knights of the Garter to be spent on charity instead of masses. But at the same time, he required new cathedrals to pray for the soul of Queen Jane. Perhaps because of the uncertainty around this belief, money left in wills for chantries (chapels for prayers for the dead) and masses dropped by half compared to the 1520s.

Forty-two Articles (1553): A Stronger Protestant Identity

Edward VI became king after Henry VIII died in 1547. During Edward's time, the Church of England became much more Protestant. The Book of Common Prayer of 1549 introduced a reformed way of worship, and the 1552 Book of Common Prayer was even more clearly Protestant. To make the English Church fully Protestant, Cranmer also planned to reform church law and create a clear statement of beliefs, which became the Forty-two Articles. Work on this statement was delayed because Cranmer was trying to get different Protestant churches to agree on beliefs to counter the Catholic Council of Trent. When this proved impossible, Cranmer focused on defining what the Church of England believed.

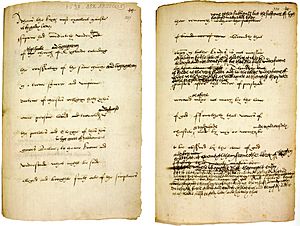

The Forty-two Articles were written by Cranmer and a small group of other Protestants. The title page claimed that the articles were approved by church leaders, but in reality, they were never discussed or adopted by them. They were also never approved by Parliament. The articles were issued by the King's command on June 19, 1553. All clergy, school teachers, and university members had to agree to them. The beliefs in these articles have been described as a "controlled" Calvinism.

How the Articles Developed

Edward VI died in 1553. When Mary I became Queen and the Church of England rejoined the Catholic Church, the Forty-two Articles were never put into effect. However, after Mary's death, they became the foundation for the Thirty-nine Articles. In 1563, church leaders met under Archbishop Parker to revise the articles. They approved only 39 of the 42. Queen Elizabeth then reduced the number to 38 by removing Article 29 to avoid upsetting her subjects who still had Catholic leanings. In 1571, despite some opposition, Article 29 was put back in. It stated that wicked people do not truly receive the Body of Christ in communion. This happened after the Queen was excommunicated by Pope Pius V in 1570. That act ended any hope of making peace with Rome, so there was no longer a need to worry about offending Catholic feelings with Article 29. The Articles, now increased to Thirty-nine, were approved by the Queen, and all bishops and clergy had to agree to them.

What the Thirty-nine Articles Say

The Thirty-nine Articles were meant to clearly state the beliefs and practices of the Church of England. They weren't meant to be a complete list of all Christian beliefs, but they explain the Church of England's position compared to Roman Catholicism, Calvinism, and Anabaptism.

|

1. Of Faith in the Holy Trinity. |

21. Of the Authority of General Councils. |

The Thirty-nine Articles can be grouped into eight sections based on what they talk about:

Articles 1–5: What We Believe About God These first five articles explain beliefs about God, the Holy Trinity (God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit), and the incarnation of Jesus Christ (God becoming human).

Articles 6–8: The Bible and Important Creeds These articles say that the Bible (Holy Scripture) has everything needed for salvation. So, no one has to believe anything that can't be proven by the Bible. The articles accept the authority of the Apostles' Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Athanasian Creed because they express what the Bible teaches. It also states that the Apocrypha is not part of Scripture. While not a basis for beliefs, the Apocrypha is still read in church for moral lessons and examples of how to live a holy life.

Articles 9–18: Sin and How We Are Saved These articles discuss original sin (the sin we are born with) and justification by faith (salvation is a gift received through faith in Christ). They reject medieval Catholic teachings that doing extra good deeds (works of supererogation) or performing good works can make a person worthy of being made right with God. They also reject the extreme Protestant idea that a person could be completely free from sin in this life. The articles talk about predestination—that "Predestination to life is the everlasting purpose of God." The idea that God has also chosen some people for reprobation (damnation) is not supported by the articles.

Articles 19–21: The Church and Its Power These articles explain what the visible church is and what power it has. They state that the church, under the Bible, has authority over matters of faith and order. Big church councils can only be called with the permission of the government. It's possible for church councils to make wrong decisions, so their actions should only be followed if they match what the Bible says.

Articles 22–24: Mistakes to Avoid in the Church These articles speak against Roman Catholic teachings on purgatory, indulgences (paying to reduce punishment for sins), using religious images, and praying to saints. Also, the Roman Catholic practice of using Latin in church services is disapproved of; instead, services should be in the local language. The articles state that no one should preach publicly or give sacraments unless they are called and authorized by proper church authority. This was meant to counter the extreme Protestant belief that any Christian could preach and act as a minister on their own, against church authorities.

Articles 25–31: The Sacraments These articles explain the Church of England's beliefs about sacraments. According to the articles, sacraments are signs of God's grace, which God works invisibly but effectively in people's lives. Through sacraments, God creates and strengthens the faith of believers. The extreme Protestant idea that sacraments are only outward signs of a person's faith is denied by the articles. While the Roman Catholic Church claimed seven sacraments, the articles recognize only two: baptism and the Lord's Supper. The five other rites called sacraments by Catholics are identified in the articles as either corrupted copies of the Apostles' practices (confirmation, penance, and extreme unction) or as "states of life allowed in the Scriptures" (holy orders and marriage).

New life, membership in the church, forgiveness of sins, and being adopted as children of God are all received through baptism. The articles state that infant baptism is "most agreeable with the institution of Christ" and should continue to be practiced. In the Lord's Supper, participants share in the body and blood of Christ and receive the spiritual benefits of Christ's death on the cross. According to the articles, this sharing should not be understood as the Roman Catholic idea of transubstantiation, which is called "against the clear words of Scripture." Instead, the articles declare that the bread and wine do not change their substance. Rather, participants are fed the body of Christ by the Holy Spirit and through faith. The articles declare that "The offering of Christ once made is the perfect redemption, forgiveness, and satisfaction for all the sins of the whole world." This was meant to reject the idea that the Mass was a sacrifice where Christ was offered again for the forgiveness of sins for the living and the dead in purgatory.

Articles 32–36: How the Church is Run The articles support the practice of clerical marriage (priests being allowed to marry) and the church's power to excommunicate people. It states that church traditions and ceremonies can change over time and in different places; national churches can change or get rid of traditions made by human authority. The First and Second Book of Homilies are said to contain correct beliefs and should be read in church. The articles also defend the ordination rites (ways of making ministers) found in the 1549 and 1552 Ordinals.

Articles 37–39: Christians and Society The articles confirm the role of the monarch (King or Queen) as the Supreme Governor of the Church of England. It rejects all claims of the Pope's power in England. It supports the state's right to use capital punishment (death penalty) and says that Christians can serve in the military. It rejects the Anabaptist teaching that Christians should share all their property, but it does explain that Christians should give alms (money or goods) to the poor and needy. It also supports the morality of taking oaths for official purposes.

Later History of the Articles

During the reign of Elizabeth I, a common understanding developed within the church about salvation, leaning towards Calvinist ideas. Article 17 only supported election to salvation and didn't say if God also chose people for damnation. However, most bishops and leading churchmen believed in double predestination. When a group with Arminian ideas (which differed from Calvinism) started to challenge this, Archbishop Whitgift issued the Lambeth Articles in 1595. These were not meant to replace the Thirty-nine Articles but to officially align Article 17 with Calvinist theology. The Queen, however, didn't want to change her religious settlement and refused to approve these new articles.

The Thirty-nine Articles are printed in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer and other Anglican prayer books. The Test Act of 1672 made agreeing to the Articles a requirement for holding public office in England until it was cancelled in 1828. Students at Oxford University were still expected to sign them until the Oxford University Act 1854 was passed.

In the Church of England, only clergy (and until the 1800s, members of Oxford and Cambridge Universities) are required to agree to the Articles. Starting in 1865, clergy affirmed that the beliefs in the Articles and the Book of Common Prayer were in line with the Bible and that they would not preach against them. Since 1975, clergy must acknowledge the Articles as one of the historical documents of the Church of England that show the faith revealed in the Bible and found in the creeds. The Church of Ireland has a similar requirement for its clergy, while some other churches in the Anglican Communion do not. The US Episcopal Church never required agreement to the Articles.

The Articles have had a deep impact on Anglican thought, beliefs, and practices. Even though Article VIII itself says that the three Catholic creeds are enough to state the faith, the Articles have often been seen as the closest thing to an extra statement of faith for the Anglican tradition. In Anglican discussions, the Articles are often used to explain beliefs and practices. Sometimes they are used to show the wide range of beliefs allowed in Anglicanism. An important example of this is the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral, which includes ideas from Articles VI, VIII, XXV, and XXXVI in its broad definition of Anglican identity. Other times, they set the boundaries of what is acceptable to believe and practice. The Articles are still used today in the Anglican Church. For example, in current debates about homosexual activity and church authority, Articles VI, XX, XXIII, XXVI, and XXXIV are often mentioned by people with different opinions.

Each of the 44 member churches in the Anglican Communion is free to adopt its own official documents. The Articles are not officially required in all Anglican Churches (nor is the Athanasian Creed). The only belief documents agreed upon by the whole Anglican Communion are the Apostles' Creed, the Nicene Creed of AD 325, and the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral. Besides these, authorized prayer books and ordination rites are important. However, the different versions of Prayer Books in various countries are not identical, though they share many similarities. No single edition of the Prayer Book is binding for the entire Communion.

A changed version of the Articles was adopted in 1801 by the US Episcopal Church, which removed the Athanasian Creed. Earlier, John Wesley, who started the Methodists, adapted the Thirty-nine Articles for use by American Methodists in the 1700s. The resulting Articles of Religion are still an official statement of belief for the United Methodist Church.

See also

In Spanish: Treinta y nueve artículos para niños

In Spanish: Treinta y nueve artículos para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |