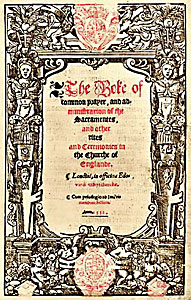

Book of Common Prayer (1552) facts for kids

The 1552 Book of Common Prayer, also known as the Second Prayer Book of Edward VI, was an important book for the Church of England. It contained the official rules and words for church services from November 1552 to July 1553.

The first Book of Common Prayer came out in 1549. It was part of the English Reformation, a time when England moved away from the Roman Catholic Church. However, many Protestants felt the 1549 book was still too much like traditional Catholic services. So, the 1552 prayer book was changed to be more clearly Protestant in its beliefs.

When Mary I became queen, she brought back Roman Catholicism. The prayer book was no longer official. But when Elizabeth I became queen, she made Protestantism the official religion again. She released the 1559 Book of Common Prayer. This was a new version based on the 1552 book. The 1559 book then became the basis for the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. This 1662 book is still used by the Church of England today.

Contents

Why the Prayer Book Changed

The first Book of Common Prayer was published in 1549. This was during the time of Edward VI. Thomas Cranmer, who was the Archbishop of Canterbury, put the book together. It was a Protestant guide for church services. It replaced the old Latin services of the Roman Rite.

In the 1549 book, the Latin Mass was replaced with an English service called communion. This first book moved the Church of England's beliefs more towards Lutheran ideas.

Making Changes Slowly

Cranmer believed it was best to make changes slowly. Because of this, the first prayer book kept some things that traditional church members liked. For example, it still used some special objects and blessings. Priests still wore traditional clothes called vestments, like the cope. They also still used stone altars for the Eucharist. The funeral service even included prayers for the dead.

Some conservative priests used these old features to make the services look more like the Latin Mass. This made Protestants in England and other countries unhappy. They felt the book could be misunderstood as still being too Catholic.

Protestant Concerns

Protestants did not like the word priest. They also disliked the continued use of altars. Both of these things suggested that the Eucharist was a sacrifice. This was a Catholic teaching, but reformers saw it as wrong.

By 1550, Protestant bishops started replacing stone altars with wooden communion tables. Eventually, the King's Privy Council ordered all altars to be removed. Nicholas Ridley explained, "An altar is for making sacrifices. A table is for people to eat upon." John Hooper, a bishop, said that as long as altars remained, people would still think of sacrifice.

Cranmer's Revisions

Cranmer started changing the prayer book in late 1549. In 1550, important Protestant thinkers like Martin Bucer and Peter Martyr Vermigli gave their opinions. Bucer found 60 problems with the book. Martyr's ideas helped add a new part about receiving communion.

Another influence might have been Valerand Poullain. The new prayer book included the Ten Commandments at the start of the communion service. This was similar to what Poullain's French church in Glastonbury did.

Stephen Gardiner wrote a book that explained the 1549 prayer book in a Catholic way. Cranmer responded by removing the parts that Gardiner liked. This made the book much more Protestant. In April 1552, Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity. This law said the new Book of Common Prayer must be used by November 1.

What Was Inside the 1552 Prayer Book

The first Book of Common Prayer (1549) was written when leaders had to make compromises. Cranmer felt that slow changes were best. He worried that people might not accept too many new ideas at once.

But by 1551, the people who opposed the changes were gone. The 1552 Prayer Book then "broke decisively with the past," as historian Christopher Haigh said. Services for baptism, confirmation, communion, and burial were rewritten. Many ceremonies that Protestants disliked were removed.

The 1552 prayer book removed many traditional rituals. These included old beliefs about blessing and exorcism of people and objects. For example, in the baptism service, babies no longer had a minor exorcism. Also, Anointing with oil was removed from services like baptism and ordination. These changes made the services focus more on faith, rather than on rituals or objects.

Church Calendar

The church calendar stayed mostly the same as in the 1549 book. The church year began with Advent, followed by Christmas and Epiphany season. Ash Wednesday started Lent, then Holy Week, Easter season, Ascensiontide, Whitsun, and Trinity Sunday.

The 1549 book only kept feast days for saints mentioned in the New Testament. But the 1552 book brought back three other saints: St. George, St. Lawrence, and St. Clement of Rome. It also brought back Lammas Day, which was an old harvest festival in England. The feast day of St. Mary Magdalene was removed.

Here are some of the saints and holidays celebrated:

- Circumcision of Christ, Epiphany, and conversion of St. Paul in January.

- Purification of the Virgin Mary and St. Matthias in February.

- Annunciation in March.

- St. George and St. Mark the Evangelist in April.

- St. Philip and St. James in May.

- St. Barnabas, the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, and St. Peter in June.

- St. James the Apostle in July.

- Lammas Day, St. Lawrence, and St. Bartholomew the Apostle in August.

- St. Matthew and Michael and All Angels in September.

- St. Luke the Evangelist, St. Simon, and St. Jude in October.

- All Saints' Day, St. Clement of Rome, and St. Andrew the Apostle in November.

- St. Thomas the Apostle, St. Stephen, St. John the Evangelist, and Holy Innocents Day in December.

The calendar also included a lectionary. This told people which parts of the Bible to read at each service. Cranmer wanted people to become very familiar with the Bible. He hoped congregations would read through the whole Bible in a year.

Morning and Evening Prayer

The Morning and Evening Prayer services were made longer. They now started with a section for saying sorry for sins and receiving forgiveness. The Bible readings for these services usually stayed the same, even on saints' days. After the 1552 Prayer Book came out, a simpler English prayer book was published in 1553. This book helped people use the prayers at home.

Holy Communion

The 1552 prayer book removed many old parts from the 1549 book. This made the communion service more Protestant. The service was now called "The Order for the Administration of the Lord's Supper or Holy Communion." The word Mass was removed.

Stone altars were replaced with communion tables. These tables were placed in the main part of the church. The priest stood on the north side. The priest wore a simple white robe called a surplice instead of traditional Mass clothes. The service suggested that Christ was present in a spiritual way, not physically, during communion.

The priest started the service by saying a prayer. Unlike the 1549 service, which had singing, the new service had the priest read the Ten Commandments. After each commandment, the people replied, "Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law."

Then, the priest said a prayer for the day and a prayer for the king. After this came readings from the Epistle and Gospel. The Nicene Creed was then recited. After the creed, there was a sermon or a reading from a book of sermons.

After the sermon, money was collected for the poor. This was not called an offertory anymore. The priest then prayed for the living church. Unlike the 1549 book, there were no prayers for those who had died.

Next, those receiving communion knelt and said sorry for their sins. The priest then gave them forgiveness. After this, the priest read comforting words from the Bible. Then came the Sursum corda, a short prayer, and the Sanctus (a hymn). This part focused on lifting hearts to God, which was a Protestant idea.

After the Sanctus, the priest knelt and said the Prayer of Humble Access.

Unlike the 1549 service, there was no special blessing of the bread and wine. Instead, the priest prayed that the people receiving communion would get Christ's body and blood:

Almighty God, our heavenly Father, who in your great kindness gave your only Son Jesus Christ to die on the Cross for us; who made there (by offering himself once) a full, perfect, and enough sacrifice for the sins of the whole world; and who started, and in his holy Gospel commanded us to continue a lasting memory of his precious death, until he comes again; Hear us, O merciful Father, we ask you; and grant that we, receiving these your gifts of bread and wine, according to your Son our Saviour Jesus Christ's holy plan, in memory of his death and suffering, may share in his most blessed body and blood . . .

After this prayer, the words of institution were said. Then, people received communion while kneeling. There was a debate about whether people should kneel or sit. John Knox was against kneeling. It was decided that people would still kneel. But the Privy Council added a special note called the Black Rubric to the prayer book. This note explained why people knelt. It said there was no "real and essential presence" of Christ's physical body and blood in the Eucharist. This was the clearest statement of beliefs about communion in the prayer book. The 1552 service removed any mention of "the body of Christ" in the words said when giving communion. This was to show that Christ's presence was spiritual.

| 1549 Book | 1552 Book |

|---|---|

For the Bread

For the Wine

|

For the Bread

For the Wine

|

Instead of special unleavened wafers, the prayer book said ordinary bread should be used. This was "to remove any old beliefs people might have." To further show that the bread and wine were not holy on their own, any leftovers were taken home by the curate to be eaten normally. This stopped people from worshipping the bread and wine kept at the altar.

After communion, the priest said the Lord's Prayer. For the next prayer, the book gave two choices: a prayer of thanks, or a prayer of praise and offering oneself to God. The service ended with the Gloria (which was sung at the beginning in the 1549 service) and a blessing.

Baptism

In the Middle Ages, the church taught that babies were born with original sin. Only baptism could remove it. So, baptism was seen as very important for salvation. People feared that children who died without baptism might not go to heaven. A priest would baptize a baby soon after birth. In emergencies, a midwife could baptize a child. The old baptism service was long and in Latin.

Cranmer believed baptism and the Eucharist were the only sacraments started by Christ himself. He did not think baptism was absolutely needed for salvation. But he did believe it was usually necessary. Refusing baptism would be like rejecting God's grace. Cranmer also believed that God chose who would be saved, which was decided beforehand. If a baby was chosen by God, dying unbaptized would not stop them from being saved.

The prayer book made public baptism the usual way. This way, the church members could watch and remember their own baptism. In emergencies, a private baptism could still be done at home.

The 1552 baptism service was simpler than the 1549 one. The 1549 service started at the church door and moved inside. The 1552 service happened entirely at the baptismal font. The priest began with these words:

Dearly loved, since all people are born in sin, and our Savior Christ says, no one can enter the kingdom of God (unless they are born again of water and the Holy Spirit); I ask you to pray to God the Father through our Lord Jesus Christ, that in his great kindness, he will give these children what they cannot have by nature, that they may be Baptized with water and the Holy Spirit, and be welcomed into Christ's holy church, and become living members of it.

The priest then said a prayer based on one by Martin Luther. It talked about Noah being saved from the flood:

Almighty and everlasting God, who in your great mercy saved Noah and his family in the Ark from dying by water: and also safely led the children of Israel, your people through the Red Sea: showing by this your holy Baptism and by the Baptism of your beloved son Jesus Christ, you made the Jordan River, and all other waters, holy for the spiritual washing away of sin: We ask you for your endless mercies, that you will kindly look upon these children, make them holy and wash them with your Holy Spirit, so that they, being saved from your anger, may be welcomed into the Ark of Christ's Church, and being strong in faith, joyful through hope, and rooted in love, may pass through the troubles of this world, so that finally they may come to the land of everlasting life, there to rule with you, forever, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

The people then prayed, "Receive [these infants] (O Lord) as you have promised by your beloved son,... that these infants may enjoy the lasting blessing of your heavenly washing, and may come to the eternal Kingdom which you have promised by Christ our Lord." In the 1549 service, the priest would have performed a minor exorcism here. But this was left out in 1552.

The idea of God welcoming the child continued with a Bible reading (Mark 10) and the minister's talk. This talk was likely meant to argue against Anabaptist beliefs that babies should not be baptized. The people then prayed for the Holy Spirit to come upon the babies:

Almighty and everlasting God, heavenly father, we give you humble thanks, that you have chosen to call us to know your grace, and faith in you: increase this knowledge, and confirm this faith in us forever: Give your holy spirit to these infants, that they may be born again, and be made heirs of everlasting salvation, through our Lord Jesus Christ: who lives and rules with you and the holy spirit, now and forever. Amen.

Baptismal vows were made by the godparents for the child. They promised to turn away from evil. The godparents also said they believed in the Apostles' Creed. This was followed by prayers from the 1549 book's blessing of the font (which was removed in the new book). It ended like this:

Almighty ever living God, whose most dearly beloved son Jesus Christ, for the forgiveness of our sins, shed out of his most precious side both water and blood, and commanded his followers that they should go teach all nations, and baptize them in the name of the father, the son, and of the holy ghost: Look, we ask you, on the prayers of your church, and grant that all your servants who shall be baptized in this water, may receive the fullness of your grace, and always remain among your faithful and chosen children, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

At this point, the child was baptized and welcomed into the church. The child was dipped once, not three times as in the 1549 service. The priest made the sign of the cross on the baby's forehead. This showed faith and obedience to Christ. Unlike the 1549 book, the child was not anointed with special oil or dressed in a white chrisom robe. The service ended with the Lord's Prayer, a prayer of thanks, and a reminder to the godparents about their duties.

Ordinal

What Happened After 1553

Edward VI died in 1553. His half-sister, Mary I, became queen. She wanted to bring England back to Roman Catholicism. So, in July 1553, the Book of Common Prayer was no longer used. It lost its legal status about a year later.

Mary quickly brought back the Latin Mass. Altars, roods (large crosses), and statues of saints were put back in churches. This was an effort to make the English Church Roman Catholic again. Cranmer was punished for his work in the English Reformation. He was burned at the stake on March 21, 1556. But the prayer book still survived.

Hundreds of English Protestants left England. They went to places like Frankfurt am Main and started English churches there. There was a big argument among them. Some, like Edmund Grindal and Richard Cox, wanted to keep using the 1552 Prayer Book exactly as it was. Others, like John Knox, felt the book still had too many compromises with Catholic ideas. This argument was called the Troubles at Frankfurt.

Eventually, in 1555, Knox and his supporters were sent away to Geneva. There, they started using a new prayer book called The Form of Prayers. This book was based on a French prayer book by John Calvin.

When Elizabeth I became queen, she brought back the Protestant Church of England. But because of the arguments in exile, some Protestants were still not happy with the Book of Common Prayer. John Knox took The Form of Prayers to Scotland. It became the basis for the Scottish Book of Common Order.

Mary I was followed by her Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth I. Elizabeth changed Mary's religious policies. She made the Church of England Protestant again. As part of her plan, the 1552 Book of Common Prayer was changed and made official again as the 1559 prayer book.

See also

Images for kids

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |