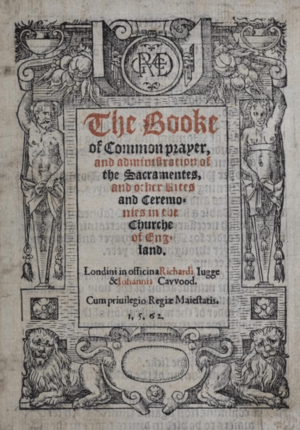

Book of Common Prayer (1559) facts for kids

The 1559 Book of Common Prayer, also known as the Elizabethan prayer book, was an important official liturgical book (a book of prayers and services) for the Church of England. It was used throughout the time Elizabeth I was queen.

Elizabeth I became Queen of England in 1558 after her Catholic half-sister Mary I died. After some uncertainty, the 1559 prayer book was approved. This was part of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, which set up the Church of England as a Protestant church. The 1559 prayer book was mostly based on the 1552 Book of Common Prayer from the time of Edward VI. It kept much of the work by Thomas Cranmer, who created the earlier versions. It was used in Anglican churches until a small update in 1604 under King James I. The 1559 style was also kept in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which the Church of England still uses today.

The 1559 prayer book was used for Elizabeth's entire 45-year reign. This made the Book of Common Prayer very important in the Church of England. Many historians see it as a way the Elizabethan church tried to find a "via media" (a middle way) between Protestant and Catholic ideas. It helped to define the specific type of Protestantism in the Church of England. Some also see it as a sign of Elizabeth's strong Protestant faith.

This book became a big part of English society in the late 1500s. The words used in the 1559 prayer book even helped shape the modern English language. Historian Eamon Duffy said the Elizabethan prayer book was a stable "re-formed" version of older medieval religious practices. He felt it "entered and possessed" the minds of English people. A. L. Rowse said it's impossible to overstate how much the Church's regular prayers influenced people.

History of the Prayer Book

Early Prayer Books and Mary's Reign

When Edward VI became King of England in 1547, his advisors supported the English Reformation. This meant changing church services to be more Protestant. Thomas Cranmer, the archbishop of Canterbury, led these changes. He had already updated some prayers under Henry VIII.

In 1549, the first Book of Common Prayer was released. It was made official by an Act of Uniformity. This book replaced the old Latin services in the Church of England.

The first prayer book mixed different influences. Some parts came from old Latin services, translated into English. A rule in the book stopped the Catholic practice of lifting the Communion bread and wine. Other Protestant changes and simplifications were added. Even though some Catholics thought the 1549 Communion service was close to their faith, some peasants started the Prayer Book Rebellion. They wanted the old services back, but their rebellion failed.

The English Reformation continued. The prayer book from Henry VIII's time was changed further. Latin prayer books were damaged or destroyed. The first Edwardine Ordinal (a book for ordaining clergy) came out in 1550. Cranmer's work on the 1552 Book of Common Prayer moved English worship even more towards Protestantism. This book was made official by another Act of Uniformity. The Black Rubric was added to the 1552 text. It explained that kneeling during Communion did not mean worshipping the bread and wine. It also said it didn't mean Christ's body and blood were truly present in a physical way.

The move towards Protestantism stopped when Edward died in 1553. His Catholic half-sister, Mary I, became queen. Mary wanted to bring England back to the Catholic Church. She brought back the old Latin Mass. Many Protestant leaders fled England to avoid being arrested or killed during the persecutions. These "exiles" went to places like Frankfurt and Geneva, where they learned about other Protestant ways of worship. Before she died in 1558, Mary had Cranmer executed.

Elizabeth Becomes Queen and the Book is Adopted

Elizabeth became queen on November 17, 1558. During Mary's reign, Elizabeth had seemed to follow Catholic practices. But many people believed Elizabeth's faith was more like her half-brother Edward VI's. Elizabeth didn't say much about her religious views at first. However, the early years of her reign would bring the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. This restored the Protestant church services from Edward's time.

By December 1558, people heard that the English Litany (a series of prayers) was being used again in Elizabeth's royal chapel. On Christmas, Elizabeth asked a bishop not to lift the Communion bread. When he refused, she left the chapel. She then had a version of Cranmer's Litany printed for use in her chapel. At her coronation and the opening of parliament in January 1559, Elizabeth changed some traditions. She walked in with her chapel singers instead of monks.

On February 9, 1559, a bill was introduced to restore the Church of England's independence from the Pope. This bill faced opposition from both Mary's bishops and some reformers. Later, two bills were introduced to create an English church service. These bills didn't last, but they led to the supremacy bill including plans for an English service. The liturgical (service) parts were removed from the bill to please conservatives. The bill passed, making Elizabeth the Supreme Governor of the Church of England.

This made the reformers in parliament unhappy. They wanted to get rid of the Pope's influence and change church services. Elizabeth might have been okay with slow changes. But the growing threats from both conservatives and unhappy reformers meant that liturgical changes became more important after Easter. Elizabeth wanted to allow everyone to receive Communion in both bread and wine, which was against Catholic practice.

On Easter Monday, John Jewel wrote about a planned debate between Catholics and Protestants. Elizabeth also started talking about "the Mass being said in English." The queen's advisors chose three topics for the debate: if services should be in English, if a national church could set its own services, and if the Mass was a sacrifice. This debate, called the Westminster Disputation, was set up to help the Protestant side win. After the first session, the Catholic leaders were arrested. This broke the power of the conservatives. A new Uniformity bill was read in parliament on April 18 and passed ten days later.

The book attached to the Act of Uniformity 1558 was the 1552 prayer book, but with "significant... alterations." One big change was removing the Black Rubric from the Communion service. Prayers against the Pope were also removed from the Litany. The new Ornaments Rubric (rules about church decorations and clergy clothes) was unclear about what vestments (special clothes) were allowed. Only the Queen's Printers were allowed to print the new prayer book. This showed how important the book was to the government. The prayer book was used in the queen's chapel on May 12 and officially introduced on June 24.

How it was Used and Opposed

The official worship in Elizabeth's church had three parts: the Litany and the approved 1559 prayer book, the 1559 Elizabethan primer (a private prayer book), and special prayers for celebrations or fasting. The Act of Uniformity required everyone to use the 1559 prayer book and attend Sunday services. People who didn't attend were fined. About 189 out of 9,400 Church of England clergy refused to use the 1559 prayer book and lost their positions. However, the act also allowed the queen to publish other texts. Elizabeth used this right in 1560 to publish Liber Precum Publicarum, a Latin version of the prayer book for use in collegiate churches (churches connected to colleges). This Latin prayer book had some changes that were more traditional, like the 1549 prayer book.

The prayer book gave clear instructions for some parts of the service but left others open to interpretation. For example, it didn't say much about music. Liturgical music (music for church services), especially by composers like Thomas Tallis and William Byrd, was created for the Elizabethan prayer book. In cathedrals and chapels, music by Byrd and others was used with organs and choirs. However, by the 1570s, these traditional music practices became less common.

In 1564, a bishop named Edmund Bonner questioned if the 1559 ordinal (the book for ordaining clergy) was legal. He argued that the ordinal wasn't mentioned in the Act of Uniformity, so ordinations might not be valid. To avoid a court ruling, the case was dropped. In 1566, parliament voted to make the 1559 ordinal and all ordinations done with it legal, even going back in time.

Another disagreement was the Vestiarian controversy. This was a debate about what clothes (vestments) clergy should wear in a reformed English church. The 1559 prayer book's Ornaments Rubric was unclear, and Elizabeth herself liked traditional vestments in her chapel. From 1559 to 1563, bishops visited churches to make sure the prayer book's rules were followed. Some bishops also met and created the "Interpretation of the Bishops" to clarify rules for worship.

By 1563, the prayer book was so established that even strong reformers, who didn't like its closeness to Catholic rituals, didn't suggest major changes. Instead, they wanted to perfect the prayer book's rules to their liking. Their ideas were similar to what the queen and bishops had already suggested. These proposals generally aimed to make English parish worship more like Protestant services in Europe. The bishops' rules from 1559 to 1563 meant that, except for the Chapel Royal and cathedrals, worship followed a reformed interpretation of the prayer book. After several failed attempts to find a compromise, Archbishop Matthew Parker's Advertisements in 1566 stopped the growing Puritan restrictions on vestments.

Still, Protestant worship from Europe, especially Calvinist ideas, continued to pressure the 1559 prayer book. John Knox had brought his version of John Calvin's service book to Scotland in 1559. This "Genevan pattern" was secretly used in London by 1567. After a revised version was printed in London in 1585, a bill was introduced in parliament to replace the 1559 prayer book with it. Elizabeth stopped this and imprisoned those involved. Some people turned to the Geneva Bible, which had Calvinist notes and teachings. This Bible was sometimes bound with the 1559 prayer book after 1583. Others bought smaller printings of the official prayer book for personal use and to show their religious identity.

The 1559 prayer book was the first English prayer book to reach the New World. Robert Wolfall, a minister on Martin Frobisher's 1578 expedition, held a Communion service when they arrived at Frobisher Bay in July.

Changes and Replacement

Puritan objections to the Elizabethan prayer book continued after Queen Elizabeth's death. When King James VI of Scotland came to England in 1603 to become king, Puritan ministers gave him the Millenary Petition. This petition asked for all Catholic influences to be removed from the church. They wanted words like "priest" and "altar" deleted. They also wanted ministers to stop saying they could forgive sins, and they wanted to stop using special vestments. King James held the Hampton Court Conference in January 1604 to discuss these issues.

The resulting 1604 prayer book was only slightly different from the 1559 text. There were some more important changes to the baptism service. A catechism (a book of religious questions and answers) was also added. The 1604 prayer book and new church laws continued the Elizabethan religious practices until the wars of the 1640s.

What was Inside the Book?

The 1559 Book of Common Prayer was an updated version of the 1552 prayer book. The changes from the 1552 text were meant to help different groups within the Church of England get along. When it first came out, the 1559 prayer book's rules allowed for more types of vestments and church decorations. The calendar increased the number of Bible readings throughout the year. It also brought back many saints' days that had been removed in the 1549 prayer book. Both the Ornaments Rubric and the calendar were changed in the 1560s to be more acceptable to the Puritans.

Still, much was kept from earlier versions. The Elizabethan prayer book had the same title as the 1552 one. Like the 1549 and 1552 prayer books, the Visitation of the Sick service said that God caused illness. The 1559 prayer book's marriage service and its allowance for ordinary people to perform baptism also stayed mostly the same. This made Puritans unhappy. The 1559 prayer book sometimes gave very detailed instructions on how a service should be done. But it was silent on some things, meaning that different churches often held services in their own ways. The prayer book didn't always clearly say how to use liturgical music with the services.

The 1560 Latin prayer book, Liber Precum Publicarum, was probably translated by Walter Haddon. It was meant for use in chapels at Oxford, Cambridge, Eton, and Winchester. Its contents were different from the English 1559 prayer book, which upset some Protestants. Most Cambridge colleges reportedly refused to use it. Some differences included a requiem service (for the dead), clergy wearing copes (special cloaks), and keeping the Communion bread and wine after the service.

Morning and Evening Prayer

Morning Prayer became the main Sunday service in smaller churches. Communion was usually held monthly, quarterly, or even less often. A typical Sunday service included Morning Prayer, the Litany, the first part of the Communion service, a sermon, and Evening Prayer with teaching.

The Ornaments Rubric appeared before Morning Prayer. Its language reversed some of the anti-ceremony parts of the 1552 prayer book. It allowed for decorations and vestments like those in the 1549 prayer book. However, this rule didn't force everyone to be uniform. This didn't stop people who liked more traditional practices, or Puritans who disliked vestments, from pushing the limits of this rule. In the 1800s, this rule was seen as allowing Mass vestments, altars, and candles. Another rule, also changing the 1552 pattern, gave details on where a minister should stand during Morning and Evening Prayer.

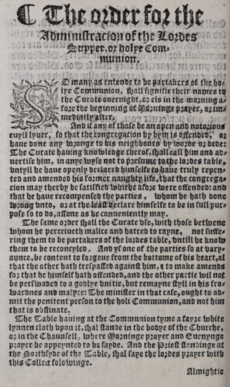

Communion Service

The service's title, The Order of the Administration of the Lord's Supper or Holy Communion, was the same as in the 1552 prayer book. It was kept in the 1662 prayer book too. A rule from the 1552 prayer book about where a priest should stand during the service was kept in both the Act of Uniformity and the 1559 text. However, Elizabeth almost immediately ignored it. During the service, two sentences from earlier prayer books were combined. This created the following passage:

The Body of our Lord Jesus Christ which was given for thee, preserve thy body and soul into everlasting life [1549]; take and eat this in remembrance that Christ died for thee and feed on him in your hearts by faith with thanksgiving [1552].

The 1559 prayer book removed the 1552 prayer book's Black Rubric. This upset Puritans. The Black Rubric was a statement about kneeling that suggested Christ was not physically present in the Communion bread and wine. Even though it was removed, people still knew its contents. The Black Rubric reappeared in the 1662 prayer book in a changed form.

Ordinal

The 1559 ordinal (the book for ordaining clergy) came from the 1552 Edwardine Ordinal. It was not listed in the prayer book's table of contents. It had a few small differences from the earlier edition. The ordinal was not always bound with the 1559 prayer book. It seems they were meant to be sold separately. The ordinal became a full part of the prayer book in the 1662 edition.

The litany (a prayer) said at the start of the 1559 deacon ordination service was changed. Edward's name was replaced with Elizabeth's, pronouns were swapped, and a prayer against the Pope was removed. A petition for the people being ordained, which was in the Edwardine ordinal, is missing in the 1559 ordinal. This might have been an accident because different printers worked on the book. The deacon ordination service also had what might have been the biggest change to the ordinal. The oath for the king's "supremacie" became one for the queen's "Soueraintee." The Pope was again not directly mentioned. However, the oath's title called it one of "Soueraintee," but the rule kept the word "supremacye." This difference stayed in Anglican prayer books for over 300 years.

Impact and Importance

For a long time, the 1559 prayer book was the second most common book in England, after only the Bible. It had a big impact on English society. It changed the direction of earlier prayer books, which had moved closer to European Protestant worship. But it also didn't go back to the 1549 version. It kept Protestantism as a key part of Elizabeth's religious plan. The Elizabethan prayer book lasted a long time. Its English services helped create the language environment that produced William Shakespeare. Shakespeare even mentioned the prayer book's regular private use in his play The Merchant of Venice.

The 1559 prayer book was slightly updated in 1604. Then, a bigger update created the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which Anglicans still use today. Historian Bryan D. Spinks said the 1559 prayer book was when the Book of Common Prayer became "the 'incomparable liturgy'" (a liturgy that couldn't be compared to others). He felt its dominance lasted until 1906. According to historian John Booty, the changes in 1661 didn't really change the feeling of the Elizabethan prayer book. Its style remained the standard in England until 1965.

Eamon Duffy, in his book The Stripping of the Altars, said that old medieval religious practices weren't replaced by the Elizabethan prayer book. Instead, they "re-formed itself around the rituals and words of the prayer-book." While he felt that "traditional religion" was "much reduced," Duffy admitted that people's regular use of the 1559 prayer book meant "Cranmer's sombrely magnificent prose, read week by week, entered and possessed their minds, and became the fabric of their prayer." A. L. Rowse agreed, saying it's impossible to overstate the influence of the Church's regular prayers and good deeds on society.

The "Middle Way" Idea

Historians have debated the reasons behind the 1559 prayer book. Especially debated is the idea that Elizabeth I was looking for a "via media" (a middle way). This "middle way" idea suggests the Elizabethan prayer book was a compromise between Catholic and Protestant influences. This view is still popular and appears in many textbooks. It often says that the queen and her advisors preferred the more Catholic-leaning 1549 prayer book. But, because of parliamentary debate, they ended up adopting the more Protestant 1552 prayer book, but with changes to make it less Protestant. Supporters of this view point to a plan from December 1558 (which suggested a committee to revise the prayer book) and a letter from Edmund Gheast to William Cecil (which suggests the committee met). They also point to the 1549 prayer book, which they believe Elizabeth preferred.

Some modern historians, like Stephen Alford and Diarmaid MacCulloch, disagree with the "middle way" idea. They try to show that Elizabeth was deeply Protestant. These historians believe Elizabeth intended to bring back the 1552 prayer book from the very start of her reign. They argue that she didn't just adapt it as a compromise. Critics of the compromise idea say it only looks at a small part of the historical evidence. Instead, they believe the evidence shows the 1559 prayer book was fundamentally Protestant from its beginnings.

A prayer book printed in 1559 by Richard Grafton, now at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, is signed by Elizabeth's privy council. This book is seen as evidence for the revisionist view. It was once thought to be an unofficial text. But now, the Corpus Christi prayer book is seen as a real, authorized text, possibly meant for limited use with the Act of Uniformity. The Corpus Christi prayer book shows changes to the 1552 prayer book. Since it's from early in the revision process and signed by Elizabeth's advisors, revisionists say the Grafton printing shows Elizabeth wanted a prayer book based on the 1552 edition, not the 1549 one.

Images for kids

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |